History of Saint Lucia

According to some, Saint Lucia was first inhabited sometime between 1000 and 500 BC by the Ciboney people, but there is not a lot of evidence of their presence on the island. The first proven inhabitants were the peaceful Arawaks, believed to have come from northern South America around 200-400 AD, as there are numerous archaeological sites on the island where specimens of the Arawaks' well-developed pottery have been found. There is evidence to suggest that these first inhabitants called the island Iouanalao, which meant 'Land of the Iguanas', due to the island's high number of iguanas.[1]

The more aggressive Caribs arrived around 800 AD, and seized control from the Arawaks by killing their men and assimilating the women into their own society.[1] They called the island Hewanarau, and later Hewanorra. This is the origin of the name of the Hewanorra International Airport in Vieux Fort. The Caribs had a complex society, with hereditary kings and shamans. Their war canoes could hold more than 100 men and were fast enough to catch a sailing ship. They were later feared by the invading Europeans for their ferocity in battle.

16th century

When the island was first discovered by Europeans is disputed. Some claim that Christopher Columbus sighted the island during his second voyage in 1493, while others claim that Juan de la Cosa noted it on his maps in 1499, and that the island is included on a globe in the Vatican made in 1502.[1] However, it is doubtful that Columbus passed St Lucia during his second voyage, as the island lies far south of his known route on that voyage; Juan de la Cosa was exploring northern South America in 1499 and it's obvious that the claim about him naming St Lucia El Falcon refers to the state Falcón in northern Venezuela; and there is no known globe in the Vatican Library from the early 1500s.

In the late 1550s the French pirate François le Clerc (known as Jambe de Bois, due to his wooden leg) set up a camp on Pigeon Island, from where he attacked passing Spanish ships.[1]

17th century

.jpg)

Around 1600, the first European camp was started by the Dutch, at what is now Vieux Fort. In 1605, an English vessel called the Olive Branch was blown off-course on its way to Guyana, and the 67 colonists started a settlement on Saint Lucia. After five weeks, only 19 survived, due to disease and conflict with the Caribs, so they fled the island.

In 1635, the French officially claimed the island but didn't settle it. Instead, it was the English who attempted the next European settlement in 1639, but that too was wiped out by the Caribs. In 1643, a French expedition sent out from Martinique by Jacques Dyel du Parquet, the governor of Martinique, established a permanent settlement on the island. De Rousselan was appointed the island's governor, took a Carib wife and remained in post until his death in 1654.

In 1664, Thomas Warner (son of the governor of St Kitts) claimed Saint Lucia for England. He brought 1,000 men to defend it from the French, but after two years, only 89 survived, mostly due to disease. In 1666 the French West India Company resumed control of the island, which in 1674 was made an official French crown colony as a dependency of Martinique.[2]

| Date | Country |

|---|---|

| 1674 | French crown colony |

| 1723 | Neutral territory (agreed by Britain and France) |

| 1743 | French colony (Sainte Lucie) |

| 1748 | Neutral territory (de jure agreed by Britain and France) |

| 1756 | French colony (Sainte Lucie) |

| 1762 | British occupation |

| 1763 | Restored to France |

| 1778 | British occupation |

| 1783 | Restored to France |

| 1796 | British occupation |

| 1802 | Restored to France |

| 1803 | British occupation |

| 1814 | British possession confirmed |

18th century

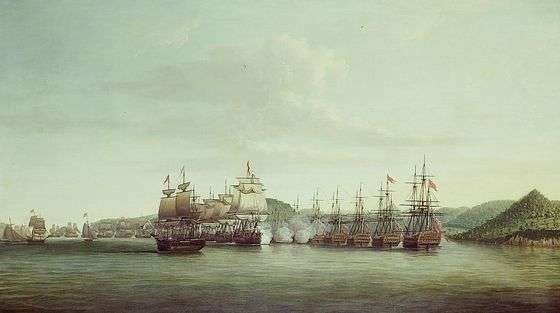

Both the British, with their headquarters in Barbados, and the French, centered on Martinique, found Saint Lucia attractive after the sugar industry developed, and during the 18th century the island changed ownership or was declared neutral territory a dozen times, although the French settlements remained and the island was a de facto a French colony well into the 18th century.

In 1722, the George I of Great Britain granted both Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent to John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu. He in turn appointed Nathaniel Uring, a merchant sea captain and adventurer, as deputy-governor. Uring went to the islands with a group of seven ships, and established settlement at Petit Carenage. Unable to get enough support from British warships, he and the new colonists were quickly run off by the French.[3]

During the Seven Years' War Britain occupied Saint Lucia for a couple of years, but gave the island back at the Treaty of Paris on 10 February 1763. Like the English and Dutch on other islands, the French began to develop the land for the cultivation of sugar cane as a commodity crop on large plantations in 1765. Colonists who came over were mostly indentured white servants serving a small percentage of wealthy merchants or nobles.

%2C_West_Indies_-_Geographicus_-_SaintLucia-bellin-1758.jpg)

Near the end of the century, the French Revolution occurred. A revolutionary tribunal was sent to Saint Lucia in 1792, headed by Captain Jean-Baptiste Raymond de Lacrosse. Prior to this, the slaves had heard about the revolution and walked off their jobs in 1790-1 to work for themselves. Bringing the ideas of the revolution to Saint Lucia, Lacrosse set up a guillotine used to execute Royalists. In 1794, the French governor of the island Nicolas Xavier de Ricard declared that all slaves were free, as also happened on Saint-Domingue.

A short time later, the British invaded in response to the concerns of the wealthy plantation owners, who wanted to keep sugar production going. On 21 February 1795, a group of rebels, led by Victor Hugues, defeated a battalion of British troops. For the next four months, a group of recently freed slaves known as the Brigands forced out not only the British army, but every white slave-owner from the island (coloured slave owners were left alone, as in Haiti). The English were eventually defeated on June 19th, and fled from the island. The Royalist planters fled with them, leaving the remaining Saint Lucians to enjoy “l’Année de la Liberté”, “a year of freedom from slavery…”. Gaspard Goyrand, a Frenchman who was Saint Lucia’s Commissary later became Governor of Saint Lucia, and proclaimed the abolition of slavery. Goyrand brought the aristocratic planters to trial. Several lost their heads on the guillotine, which had been brought to Saint Lucia with the troops. He then proceeded to re-organize the island. [4]

The British continued to harbor hopes of recapturing the island and in April 1796 Sir Ralph Abercrombie and his troops attempted to do so. Castries was burned as part of the conflict, and after approximately one month of bitter fighting the French surrendered at Morne Fortune on 25th May. General Moore was elevated to the position of Governor of Saint Lucia by Abercrombie and was left with 5,000 troops to complete the task of subduing the entire island. [5]

19th century

In 1803, the British finally regained control of the island and restored slavery. Many of the rebels escaped into the thick rain forests, where they evaded capture and established maroon communities.[6] The same year, the French withdrew their forces from Saint-Domingue after losing two-thirds of the 20,000 soldiers they had sent there against the slave revolt. The new leaders of Haiti declared its independence in 1804, the first black republic in the Caribbean, and the second republic in the Western Hemisphere.

The British abolished the African slave trade in 1807; they acquired Saint Lucia permanently in 1814. It was not until 1834 that they abolished the institution of slavery. Even after abolition, all former slaves had to serve a four-year "apprenticeship," during which they had to work for free for their former masters for at least three-quarters of the work week. They achieved full freedom in 1838. By that time, people of African ethnicity greatly outnumbered those of ethnic European background. Some people of Carib descent also comprised a minority on the island.

Also in 1838, Saint Lucia was incorporated into the British Windward Islands administration, headquartered in Barbados. This lasted until 1885, when the capital was moved to Grenada.

20th century to 21st century

Increasing self-government has marked St Lucia's 20th-century history. A 1924 constitution gave the island its first form of representative government, with a minority of elected members in the previously all-nominated legislative council. Universal adult suffrage was introduced in 1951, and elected members became a majority of the council. Ministerial government was introduced in 1956, and in 1958 St. Lucia joined the short-lived West Indies Federation, a semi-autonomous dependency of the United Kingdom. When the federation collapsed in 1962, following Jamaica's withdrawal, a smaller federation was briefly attempted. After the second failure, the United Kingdom and the six windward and leeward islands—Grenada, St. Vincent, Dominica, Antigua, St. Kitts and Nevis and Anguilla, and St. Lucia—developed a novel form of cooperation called associated statehood.

As an associated state of the United Kingdom from 1967 to 1979, St. Lucia had full responsibility for internal self-government but left its external affairs and defense responsibilities to the United Kingdom. This interim arrangement ended on February 22, 1979, when St. Lucia achieved full independence. St. Lucia continues to recognize Queen Elizabeth II as titular head of state and is an active member of the Commonwealth of Nations. The island continues to cooperate with its neighbors through the Caribbean community and common market (CARICOM), the East Caribbean Common Market (ECCM), and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS).

See also

- British colonization of the Americas

- French colonization of the Americas

- History of the Americas

- History of the British West Indies

- History of North America

- History of the Caribbean

- List of colonial governors of Saint Lucia

- List of Prime Ministers of Saint Lucia

- Politics of Saint Lucia

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

References

- 1 2 3 4 All about St Lucia: History

- 1 2 World Statesmen: Saint Lucia Chronology Linked 2014-01-20

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Montagu, John (1688?-1749)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Montagu, John (1688?-1749)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - ↑ http://soufrierefoundation.org/about-soufriere/history

- ↑ http://soufrierefoundation.org/about-soufriere/history

- ↑ They Called Us the Brigands. The Saga of St. Lucia's Freedom Fighters by Robert J Devaux

- Philpott, Don (1999). St Lucia. Derbyshire: Landmark Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-901522-28-8.

- Higgins, Chris (2001). St. Lucia. Montreal: Ulysses Travel Guides. ISBN 2-89464-396-9.

- "History of Saint Lucia". History of Saint Lucia. Retrieved September 23, 2005.

Further reading

- Jolien Harmsen; Guy Ellis; Robert Devaux (2012). A History of St Lucia. Vieux Fort, Saint Lucia: At the presses of Lighthouse Road Publications.

- Jedidiah Morse (1797). "St. Lucia". The American Gazetteer. Boston, Massachusetts: At the presses of S. Hall, and Thomas & Andrews.

- All about St Lucia: History

- Website for the Permanent Mission of St. Lucia to the United Nations: History of Saint Lucia