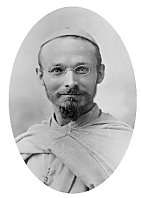

Henri Streicher

| Mgr. Henri Streicher C.B.E. | |

|---|---|

| Vicar Apostolic of Uganda (ex-Apostolic Vicariate of Northern Victoria Nyanza) | |

| |

| Appointed | 1 February 1897 |

| Term ended | 2 June 1933 |

| Predecessor | Antonin Guillermain |

| Successor | Joseph Georges Edouard Michaud |

| Other posts |

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 23 September 1887 |

| Consecration |

15 August 1897 by Bishop John Joseph Hirth |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

29 July 1863 Wasselonne, France |

| Died |

7 July 1952 (aged 88) Villa Maria, north of Masaka, Uganda |

| Nationality | French |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Profession | Missionary Bishop |

Henri Streicher, C.B.E. (29 July 1863 – 7 June 1952) was a Roman Catholic missionary bishop who served as Vicar Apostolic of Uganda from 1897 to 1933.

Early years

Henri Streicher was born on 29 July 1863 in Wasselonne, France. On 23 September 1887 he was ordained a Priest of the White Fathers (Society of the Missionaries of Africa).[1] For two years he taught Church History and Bible at the Greek Melchite Seminary in Jerusalem. After that he taught Systematic Theology at the White Fathers "scholasticate" at Carthage for a year.[2]

Missionary

In 1890 Streicher was appointed to the Apostolic Vicariate of Victoria Nyanza led by Bishop John Joseph Hirth, which he reached in 1891. He was assigned to Buddu in the south of the Buganda kingdom. In 1892 there was a civil war in Uganda, during which the supporters of the Catholics had to move to Buddu. Soon after the fighting ended Streicher established the Villa Maria mission (near Masaka).[2] Victoria Nyanza was divided into three parts in 1894. Hirth took the Apostolic Vicariate of Southern Nyanza, the English Mill Hill Missionaries took the eastern part, called the Apostolic Vicariate of Upper Nile, and Bishop Antonin Guillermain took the western part, called the Apostolic Vicariate of Northern Nyanza. In 1896 Guillermain died of a Viral hemorrhagic fever. The next year Streicher, acting as head of the Roman Catholic mission since his death, was appointed his successor.[2]

Bishop

On 1 February 1897 Streicher was appointed Titular Bishop of Thabraca and Vicar Apostolic of Northern Victoria Nyanza in what is now Uganda.[1] He decided that he would not return to Europe to be consecrated, and was ordained on 15 August 1897 in the small church of Kamoga at Bukumbi (in what is now Tanzania) by Bishop John Joseph Hirth assisted by two priests.[3] He made his headquarters at Villa Maria. His vicariate included all of the south and west of modern Uganda, and included 30,000 baptized Christians when he became Apostolic Vicar.[2]

Bishop Guillermain had already begun to evangelize the Nyoro and Toro kingdoms in the west of the country. Streicher began missionary activity in Ankole in 1902, and in Kigezi twenty years later. He was authoritarian, using his diocesan synods to present decisions rather than encouraging debate. The chiefs who had converted to Catholicism moved to Buddu, and treated him as both civil and religious leader, equivalent to a king. Streicher assumed some of the royal trappings in his costume. The chiefs sent their sons to be his pages at his court, and they ensured that their followers were converted by the Ganda catechists.[2]

Streicher was a strong believer in education and set up schools throughout his territory. He founded a training college for catechists in 1902. He required that students know the alphabet before being admitted to the catechumenate, and that they were literate before they could be baptized. Until 1916 he resisted allowing English to be used in his schools, thinking that would encourage his students to engage in worldly pursuits. The result was that the Catholics became disadvantaged compared to Protestants in English-administered Uganda. Streicher did allow English in St. Mary's Lubaga, founded in 1906 for the sons of chiefs. He saw Catholic teaching orders as a potential threat to his authority, and did not allow them to enter the diocese until 1924, when the Canadian Brothers of Christian Instruction of Ploermel were permitted to launch St. Mary's College Kisubi and to open other schools.[2]

Streicher consider that training indigenous priests was the first priority, more important than conversion of the people. He inherited the seminary at Kisubi, later moved to Bukalasa, near to Villa Maria. In 1911 the senior seminarians moved to Katigondo. In 1913 Streicher ordained the first two African priests of the colonial era.[2] In 1913 and 1914 Streicher headed a commission charged with assembling the testiminials needed to beatify the Uganda Martyrs.[4] World War I seriously affected the mission, with 31 of the 63 priests who could travel being recalled to France, and with subsidies cut off.[4] On 15 Jan 1915 his Vicariate Apostoloc was as Vicariate Apostolic of Uganda and he remained at his post until his resignation on 2 June 1933.[1] In May 1920 he assisted at the solemn beatification ceremony of the Uganda Martyrs in Rome.[4] Streicher pushed hard to prepare for the diocese to become autonomous from European assistance, causing resentment from missionaries who felt that more time was needed.[2]

Legacy

Streicher resigned in 1933 and became Titular Archbishop. By then his vicariate had 303,000 baptized Christians. His mission was separated into the vicariates of Rubaga and Masaka.[2] After resigning he was appointed Titular Archbishop of Brysis.[1] The future diocese that he left at his retirement was far in advance of any other at that time.[3] In 1939 he assisted Pope Pius XII at the consecration of Joseph Kiwánuka in St Peter's, Rome. Kiwanuka, who was the first African bishop since the days of the early church, became Vicar Apostolic of Masaka.[3] Streicher made his home in Ibanda. On 7 June 1952 he received the last rites from Bishop Kiwanuka before his death. He was interred in his church that he had built at Villa Maria.[2] He was described by Cardinal Costantini as "the greatest missionary of the twentieth century."[3]

Bibliography

- Streicher, Henri (1923). Statuts synodaux du vicariat de l'Uganda. s.n. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Streicher, Henri (1931). The Martyrs of Uganda Beatified on June 6th, 1920. Catholic Truth Society. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Streicher, Henri (1933). Les bienheureux martyrs de l'Ouganda. Procures des Missionnaires d'Afrique (Pères Blanc). Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Streicher, Henri (1933). Instructions pastorales de son Excellence Monseigneur Streicher Vicaire Apostolique de l'Uganda, a ses missionnaires. Uganda Protectorate. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Streicher, Henri (1956). Le Bûcher de Namougongo. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

References

Sources

- Blatz, Jean-Paul (1987). "STREICHER Henri". Dictionnaire du monde religieux dans la France contemporaine: Tome 2, L'Alsace de 1800 à 1962. Editions Beauchesne. ISBN 978-2-7010-1141-7. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Cheney, David M. (28 Jan 2013). "Archbishop Henri Streicher, M. Afr.". Catholic Hierarchy. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Hastings, Adrian (1995-01-05). The Church in Africa, 1450–1950. Oxford University Press. p. 565. ISBN 978-0-19-152055-6. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Shorter, Aylward (2003). "Bishop Streicher, Henri 1863 to 1952". Missionaries of Africa. Retrieved 2013-04-06.