Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park

| Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

| |

| |

| Location | Hawaii County, Hawaii, USA |

| Nearest city | Hilo |

| Coordinates | 19°23′0″N 155°12′0″W / 19.38333°N 155.20000°WCoordinates: 19°23′0″N 155°12′0″W / 19.38333°N 155.20000°W |

| Area | 323,431 acres (130,888 ha)[1] |

| Established | August 1, 1916 |

| Visitors | 1,832,660 (in 2015)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park |

| Official name | Hawaii Volcanoes National Park |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | viii |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 409 |

| State Party |

|

| Region | Europe and North America |

Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, established in 1916, is a United States National Park located in the U.S. State of Hawaii on the island of Hawaii. It encompasses two active volcanoes: Kīlauea, one of the world's most active volcanoes, and Mauna Loa, the world's most massive shield volcano. The park delivers scientists insight into the birth of the Hawaiian Islands and ongoing studies into the processes of volcanism. For visitors, the park offers dramatic volcanic landscapes as well as glimpses of rare flora and fauna.

In recognition of its outstanding natural values, Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park was designated as an International Biosphere Reserve in 1980 and a World Heritage Site in 1987.[3] In 2012 the Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park was honored on the 14th quarter of the America the Beautiful Quarters series.

Environment

The park includes 323,431 acres (505.36 sq mi; 1,308.88 km2) of land.[4] Over half of the park is designated the Hawaii Volcanoes Wilderness area and provides unusual hiking and camping opportunities. The park encompasses diverse environments that range from sea level to the summit of the Earth's most massive active volcano, Mauna Loa at 13,677 feet (4,169 m). Climates range from lush tropical rain forests, to the arid and barren Kaʻū Desert.

Active eruptive sites include the main caldera of Kīlauea and a more active but remote vent called Puʻu ʻŌʻō.[5]

The main entrance to the park is from the Hawaii Belt Road. The Chain of Craters Road, as the name implies, leads past several craters from historic eruptions to the coast. It used to continue to another entrance to the park near the town of Kalapana, but that portion is now covered by a lava flow.

History

Kīlauea and its Halemaʻumaʻu caldera were traditionally considered the sacred home of the volcano goddess Pele, and Hawaiians visited the crater to offer gifts to the goddess. In 1790, a party of warriors (along with women and children who were in the area) were caught in an unusually violent eruption. Many were killed and others left footprints in the lava that can still be seen today.[6]

The first western visitors to the site, English missionary William Ellis and American Asa Thurston, went to Kīlauea in 1823. Ellis wrote of his reaction to the first sight of the erupting volcano:

A spectacle, sublime and even appalling, presented itself before us. 'We stopped and trembled.' Astonishment and awe for some moments rendered us mute, and, like statues, we stood fixed to the spot, with our eyes riveted on the abyss below.[7]

The volcano became a tourist attraction in the 1840s, and local businessmen such as Benjamin Pitman and George Lycurgus ran a series of hotels at the rim.[8] Volcano House is the only hotel or restaurant located within the borders of the national park.

Lorrin A. Thurston, grandson of the American missionary Asa Thurston, was one of the driving forces behind the establishment of the park after investing in the hotel from 1891 to 1904. William R. Castle first proposed the idea in 1903. Thurston, who then owned the Honolulu Advertiser newspaper, printed editorials in favor of the park idea. In 1907, the territory of Hawaii paid for fifty members of Congress and their wives to visit Haleakala and Kīlauea. It included a dinner cooked over lava steam vents. In 1908 Thurston entertained Secretary of the Interior James Rudolph Garfield, and in 1909 another congressional delegation. Governor Walter F. Frear proposed a draft bill in 1911 to create "Kilauea National Park" for $50,000. Thurston and local landowner William Herbert Shipman proposed boundaries, but ran into some opposition from ranchers. Thurston printed endorsements from John Muir, Henry Cabot Lodge, and former President Theodore Roosevelt.[9] After several attempts, the legislation introduced by delegate Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana'ole finally passed to create the park. House Resolution 9525 was signed by Woodrow Wilson on August 1, 1916. It was the 11th National Park in the United States, and the first in a Territory.[10]

Within a few weeks, the National Park Service Organic Act would create the National Park Service to run the system.[11] Originally called "Hawaii National Park", it was split from the Haleakalā National Park on September 22, 1960.

An easily accessible lava tube was named for the Thurston family. An undeveloped stretch of the Thurston Lava Tube extends an additional 1,100 ft (340 m) beyond the developed area and dead-ends into the hillside, but it is closed to the general public.

In 2004, an additional 115,788 acres (468.58 km2) of Kahuku Ranch were added to the park, making it 56% larger. This was an area west of the town of Waiʻōhinu and east of Ocean View, the largest land acquisition in Hawaii's history. The land was bought for US$21.9 million from the Samuel Mills Damon Estate, with financing from the Nature Conservancy.[4]

Historic places

Several of the National Register of Historic Places listings on the island of Hawaii are located within the park:

- 1790 Footprints

- Ainahou Ranch

- Ainapo Trail

- Kilauea Crater

- Puna-Ka'u Historic District

- Volcano House

- Whitney Seismograph Vault No. 29

- Wilkes Campsite

Visitor center and museums

- The main visitor center, located just within the park entrance at 19°25′46″N 155°15′25.5″W / 19.42944°N 155.257083°W, includes displays and information about the features of the park.

- The nearby Volcano Art Center, located in the original 1877 Volcano House hotel, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and now houses historical displays and an art gallery.

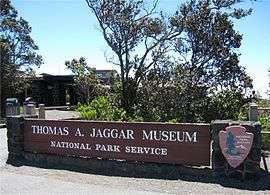

- The Thomas A. Jaggar Museum, located a few miles west on Crater Rim Drive, features more exhibits and a close view of the Kīlauea's active vent Halemaʻumaʻu. The museum is named after scientist Thomas Jaggar, the first director of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, which adjoins the museum. The observatory itself is operated by the U.S. Geological Survey and is not open to the public. Bookstores are located in the main visitor center and the Jaggar Museum.[12]

- The Kilauea Military Camp provides accommodations for U.S. military personnel.[13]

As of 2008 the superintendent was Cindy Orlando.[4] Volunteer groups also sponsor events in the park.[14]

Painting of Pele

About 1929, D. Howard Hitchcock made an oil painting of Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of fire, lightning, wind, and volcanoes. In 1966, the artist's son, Harvey, donated the painting to the Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, where it was displayed in the visitors' center from 1966 to 2005.[15] The painting was criticized for portraying the Hawaiian goddess as a Caucasian.[15]

In 2003, the Volcano Art Center announced a competition for a "more modern and culturally authentic rendering" of the goddess.[16] An anonymous judging panel of Native Hawaiian elders selected a painting by Arthur Johnsen of Pahoa, Hawaii from 140 entries. In Johnsen's painting, the goddess has distinctly Polynesian features. She is holding a digging stick (ʻōʻō) in her left hand and the egg that gave birth to her younger sister Hiʻiaka in her right hand.[16] In 2005, the Hitchcock was replaced with Johnsen's painting.

Recent events

On March 19, 2008, there was a small explosion in Halemaʻumaʻu crater, the first explosive event since 1924 and the first eruption in the Kīlauea caldera since September 1982. Debris from the explosion was scattered over an area of 74 acres (300,000 m2). A small amount of ash was also reported at a nearby community. The explosion covered part of Crater Rim Drive and damaged Halemaʻumaʻu Overlook. The explosion did not release any lava, which suggests to scientists that it was driven by hydrothermal or gas sources.[17]

This explosion event followed the opening of a major sulfur dioxide gas vent, greatly increasing levels emitted from the Halemaʻumaʻu crater. The dangerous increase of sulfur dioxide gas has prompted closures of Crater Rim Drive between the Jaggar Museum south/southeast to Chain of Craters Road, Crater Rim Trail from Kīlauea Military Camp south/southeast to Chain of Craters Road, and all trails leading to Halemaʻumaʻu crater, including those from Byron Ledge, ʻIliahi (Sandalwood) Trail, and Kaʻū Desert Trail.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- ↑ "Hawai'i's Only World Heritage Site". Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park web site. National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- 1 2 3 "2008 Business Plan" (PDF). Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "Kilauea Status Page". HVO. USGS.

- ↑ Nakamura, Jadelyn (2003). "Keonehelelei – the falling sands" (PDF). Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Archaeological Inventory of the Footprints Area.

- ↑ "Early Kilauea Explorations". Hawaii Nature Notes number 2. National Park Service. November 1953. Retrieved 2000-12-01. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The Volcano House". Hawaii Nature Notes number 2. National Park Service. November 1953. Retrieved 2000-12-01. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The Park Idea". Hawaii Nature Notes number 2. National Park Service. November 1953. Retrieved 2000-12-01. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The Final Thrust". Hawaii Nature Notes number 2. National Park Service. November 1953. Retrieved 2000-12-01. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The National Park Service Organic Act". statutes of the 64th United States Congress. National Park Service. August 25, 1916. Retrieved 2000-12-01. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Hawai'i Natural History Association". official web site. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "Kilauea Military Camp at Kilauea Volcano, a Joint Services Recreation Center". official web site. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "Friends of Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park". official web site. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- 1 2 Rod Thompson (July 13, 2003). "Rendering Pele: Artists gather paints and canvas in effort to be chosen as Pele's portrait maker". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- 1 2 Thompson, Rod (August 15, 2003). "Winning Vision of Pele, an Unusual Take". Honolulu Star Bulletin. p. A3.

- ↑ "Explosive eruption in Halemaʻumaʻu Crater, Kilauea Volcano". HVO. USGS. Archived from the original on 2008-03-23.

- ↑ "Closed Areas". Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park web site. National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

External links

- "Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- Official Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park website

- Volcano Gallery: Hawaii Volcanoes National Park - Local Info Photo Gallery, Volcano Live Cam, Eruption Update and General Park Information.

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. HI-47, "Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Roads, Volcano, Hawaii County, HI", 6 photos, 20 measured drawings, 116 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. HI-76, "Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Water Collection System, Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, Volcano, Hawaii County, HI", 51 photos, 40 measured drawings, 43 data pages, 5 photo caption pages

- HAER No. HI-48, "Crater Rim Drive, Volcano, Hawaii County, HI", 17 photos, 1 color transparency, 3 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- HAER No. HI-48, "Chain of Craters Road, Volcano, Hawaii County, HI", 7 photos, 1 color transparency, 3 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. HI-50, "Mauna Loa Road, Volcano, Hawaii County, HI", 13 photos, 1 color transparency, 3 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. HI-51, "Hilina Pali Road, Volcano, Hawaii County, HI", 8 photos, 1 color transparency, 3 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. HI-523, "Namakani Paio Campground, Highway 11, Volcano, Hawaii County, HI", 6 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page