Hashima Island

| Native name: <span class="nickname" ">端島 Nickname: Battleship Island | |

|---|---|

|

Aerial view | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Northeast Asia |

| Area rank | none |

| Administration | |

| Prefecture | Nagasaki Prefecture |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 (2016) |

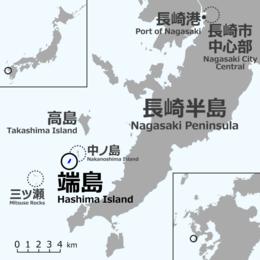

Hashima Island (端島 or simply Hashima — -shima is a Japanese suffix for island), commonly called Gunkanjima (軍艦島; meaning Battleship Island), is an abandoned island lying about 15 kilometers (9 miles) from the city of Nagasaki, in southern Japan. It is one of 505 uninhabited islands in Nagasaki Prefecture. The island's most notable features are its abandoned concrete buildings, undisturbed except by nature, and the surrounding sea wall. While the island is a symbol of the rapid industrialization of Japan, it is also a reminder of its dark history as a site of forced labor prior to and during the Second World War.[1][2]

The 6.3-hectare (16-acre) island was known for its undersea coal mines, established in 1887, which operated during the industrialization of Japan. The island reached a peak population of 5,259 in 1959. In 1974, with the coal reserves nearing depletion, the mine was closed and all of the residents departed soon after, leaving the island effectively abandoned for the following three decades. Interest in the island re-emerged in the 2000s on account of its undisturbed historic ruins, and it gradually became a tourist attraction of a sort. Certain collapsed exterior walls have since been restored, and travel to Hashima was re-opened to tourists on April 22, 2009. Increasing interest in the island resulted in an initiative for its protection as a site of industrial heritage. The island was formally approved as a UNESCO World Heritage site in July 2015, as part of Japan's Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining.[3]

Etymology

Battleship Island is an English translation of the Japanese nickname for Hashima Island, Gunkanjima (gunkan meaning battleship, jima being the rendaku form of shima, meaning island). The island's nickname came from its resemblance to the Japanese battleship Tosa.[4]

History

Coal was first discovered on the island around 1810, and the island was permanently populated from 1887 to 1974 as a seabed coal mining facility. Mitsubishi Goshi Kaisha bought the island in 1890 and began extracting coal from undersea mines, while seawalls and land reclamation (which tripled the size of the island) were constructed. Four main mine-shafts (reaching up to 1 kilometre deep) were built, with one actually connecting it to a neighbouring island. Between 1891 and 1974 around 15.7 million tons of coal were excavated in mines with temperatures of 30°C and 95% humidity.

In 1916 the company built Japan's first large reinforced concrete building (a 7 floor miner`s apartment block),[5] to accommodate their burgeoning ranks of workers. Concrete was specifically used to protect against typhoon destruction. Over the next 55 years, multiple buildings were also constructed ranging from other apartment blocks, a school, kindergarten, hospital, town hall, and a community centre. For entertainment, a clubhouse, cinema, communal bath, swimming pool, rooftop gardens, shops, and a pachinko parlour were also built for the miners and their families.

Beginning in the 1930s and until the end of the Second World War, Korean conscripted civilians and Chinese prisoners-of-war were forced to work under very harsh conditions and brutal treatment at the Mitsubishi facility as forced laborers under Japanese wartime mobilization policies.[1][6][7][8] During this period, it is estimated that about 1,300 of those conscripted laborers had died on the island due to various reasons including underground accidents, exhaustion and malnutrition.[9]

In 1959, the 6.3-hectare (16-acre) island's population reached its peak of 5,259, with a population density of 835 people per hectare (83,500 people/km2, 216,264 people per square mile) for the whole island, or 1,391 per hectare (139,100 people/km2) for the residential district.[10]

As petroleum replaced coal in Japan in the 1960s, coal mines began shutting down across the country, and Hashima's mines were no exception. Mitsubishi officially closed the mine in January 1974, and the island was cleared of inhabitants by April. Today its most notable features are the abandoned and still mostly-intact concrete apartment buildings, the surrounding sea wall, and its distinctive profile shape. The island has been administered as part of Nagasaki city since the merger with the former town of Takashima in 2005. Travel to Hashima was re-opened on April 22, 2009, after 35 years of closure.[11]

Current status

The island was owned by Mitsubishi until 2002, when it was voluntarily transferred to Takashima Town. Currently, Nagasaki City, which absorbed Takashima Town in 2005, exercises jurisdiction over the island. On August 23, 2005 landing was permitted by the city hall to journalists only. At the time, Nagasaki City planned the restoration of a pier for tourist landings in April 2008. In addition a visitor walkway 220 metres (722 feet) in length was planned, and entry to unsafe building areas was to be prohibited. Due to the delay in development construction, however, at the end of 2007 the city announced that public access was delayed for approximately one year until spring 2009. Additionally the city encountered safety concerns, arising from the risk of collapse of the buildings on the island due to significant aging.

It was estimated that landing of tourists would only be feasible for fewer than 160 days per year because of the area's harsh weather. For reasons of cost-effectiveness the city considered cancelling plans to extend the visitor walkway further—for an approximate 300 metres (984 feet) toward the eastern part of the island and approximately 190 meters (623 feet) toward the western part of the island—after 2009. A small portion of the island was finally re-opened for tourism in 2009, but over 95% of the island is strictly delineated as off-limits during tours.[12] A full re-opening of the island would require substantial investment in safety, and detract from the historical state of the aged buildings on the property.

The island is increasingly gaining international attention not only generally for its modern regional heritage, but also for the undisturbed housing complex remnants representative of the period from the Taishō period to the Shōwa period. It has become a frequent subject of discussion among enthusiasts for ruins. Since the abandoned island has not been maintained, several buildings have collapsed mainly due to typhoon damage, and other buildings are in danger of collapse. However, some of the collapsed exterior walls have been restored with concrete.[13]

World Heritage Site approval controversy

Japan's 2009 request to include Hashima Island, among with 22 other industrial sites, to be added to the UNESCO World Heritage Site list was initially opposed by South Korean authorities on the grounds that Korean and Chinese forced laborers were used on the island prior to and during World War II. North Korea also criticized the World Heritage bid because of this same issue.[14]

A week before the beginning of the 39th UNESCO World Heritage Committee (WHC) meeting in Bonn, Germany, Korea and Japan came to a compromised agreement that Japan would include the use of forced labor in the explanation of facilities in relevant sites and both nations would cooperate towards the approval of each other's World Heritage Site candidates.[15][16]

In July 2015, during the WHC meeting, South Korea withdrew its opposition after Japan's acknowledgement of this issue as part of the history of the island, specifically noting that "there were a large number of Koreans and others who were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some of the sites [including Hashima island]"[16][17][18][19] and that Japan was "prepared to incorporate appropriate measures into the interpretive strategy to remember the victims such as the establishment of information center".[16][17][20] The site was subsequently approved for inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage list on July 5.

On the same day, immediately after the UNESCO WHC meeting, Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida publicly announced that "the remarks [forced to work under harsh conditions] by the Japanese government representative did not mean 'forced labor'".[21][22]

A monitoring mechanism for the implementation of 'the measures to remember the victims' is set up by the World Heritage Committee and it will be assessed during the World Heritage Committee Session in 2018.[20] The official tourism website and tour program for the island operated by Nagasaki City does not currently mention this acknowledgement.[23]

Access

When people resided on the island, the Nomo Shosen line served the island from Nagasaki Port via Iōjima Island and Takashima Island. Twelve round-trip services were available per day in 1970. It took 50 minutes to travel from the island to Nagasaki. After all residents left the island, this direct route was discontinued.

Since 2009 the island has been open once again for public visits.[11][24] Sightseeing boat trips around or to the island are currently provided by five operators; Gunkanjima Concierge, Gunkanjima Cruise Co., Ltd., Yamasa-Kaiun, and Takashima Kaijou from Nagasaki Port, and a private service from the Nomozaki Peninsula. Landing access to the island costs ¥300 per person, exclusive of the cost of boat travel.

Media

In 2002, Swedish filmmaker Thomas Nordanstad visited the island with a Japanese man named Dotokou, who grew up on Hashima. Nordanstad documented the trip in a film called Hashima, Japan, 2002.[25]

During the 2009 Mexican photography festival FotoSeptiembre, Mexican photographers Guillaume Corpart Muller and Jan Smith, along with Venezuelan photographer Ragnar Chacin, showcased images from the island in the exhibition "Pop. Density 5,000/km2". The exhibition traced urban density and the rise and fall of cities around the world.[26]

In 2009 the island was featured in History Channel's Life After People, first-season episode "The Bodies Left Behind" as an example of the decay of concrete buildings after only 35 years of abandonment.[27]

The island was again featured in 2011 in episode six of a 3D production for 3net, Forgotten Planet discussing the island's current state, history and unauthorized photo shoots by urban explorers.[28] The Japanese Cultural Institute in Mexico used the images of Corpart Muller and Smith in the photography exhibition "Fantasmas de Gunkanjima", organized by Daniela Rubio, as part of the celebrations surrounding 200 years of diplomacy between Mexico and Japan.[29]

More recently in 2015, the island was featured in the fourth episode of the Science channel's series "What On Earth." Discussed were the island's history and it being the most densely populated place on the planet at one time, and included satellite images and a tour of many of the buildings.

Sony featured the island in a video promoting one of its video cameras. The camera was mounted onto a mini multi-rotor radio-controlled helicopter and flown around the island and through many buildings. The video was posted on YouTube in April 2013.[30]

In 2013 Google sent an employee to the island with a Street View backpack to capture its condition in panoramic 360-degree views and allow users to take a virtual walk across the island. Google also used its Business Photos technology to let users look inside the abandoned buildings, which still contain such items as old black-and-white TVs and discarded soda bottles.[31]

The island has appeared in a number of recent feature films. External shots of the island were used in the 2012 James Bond film Skyfall.[25] The 2015 live-action Japanese films based on the manga Attack on Titan used the island for filming multiple scenes.[32]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Battleship island – a symbol of Japan's progress or reminder of its dark history?". The Guardian. 2015-07-03. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- ↑ "Dark history: A visit to Japan's creepiest island". CNN. 2013-06-13. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- ↑ http://whc.unesco.org/en/newproperties/date=2015&mode=list

- ↑ Kawamoto, Yashuhiko. "Deserted 'Battleship Isle' may become heritage ghost ship," The Japan Times. February 17, 2009.

- ↑ Der Spiegel (Article) (in German), DE

- ↑ "1999 report of the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations" (PDF). the International Labour Organization. 1999. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- ↑ "Japan's 007 island still carries scars of wartime past, Compulsory Mobilization".

- ↑ "Hashima ― forgotten island of tragedy". The Korea times. 2012-10-04. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

- ↑ Burke-Gaffney, Brian (1996). "Hashima: The Ghost Island". Crossroads: a Journal of Nagasaki History and Culture. 4: 33–52. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ↑ "Japan's 007 island still carries scars of wartime past". CNN. 2013-06-13. Retrieved 2013-08-22.

- 1 2 "Abandoned 'Battleship Island' to reopen to public in Nagasaki". Japan. The Mainichi Daily News. 21 April 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-04-22. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ↑ Bender, Andrew. "The Mystery Island From 'Skyfall' And How You Can Go There". Forbes. Forbes, Inc. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ↑ Pulin. 昔の思い出 昭和末期の長崎の端島(いわゆる軍艦島)のこと (in Japanese). Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ Leo Byrne (20 May 2015). "North Korea lashes out at Japan's UNESCO candidates". NK News. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ↑ "Japan, S. Korea agree to cooperate on respective World Heritage site candidacies". The Asahi. 2015-06-22. Retrieved 2015-09-18.

- 1 2 3 "Japan, Korea Breakthrough: Japanese Repenting 'Forced' Korean Labor On UNESCO Heritage Sites". Forbes Asia. 2015-07-06. Retrieved 2015-09-18.

- 1 2 "Japan forced labour sites receive world heritage status". The Telegraph. 2015-07-06. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- ↑ "Japan sites get world heritage status after forced labour acknowledgement". The Guardian. 2015-07-06. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- ↑ "Government downplays forced labor concession in winning UNESCO listing for industrial sites". The Japan Times. 2015-07-06. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- 1 2 "The History that a large number of Koreans were forced to work against their will is reflected in the inscription of Japan's Meiji Industrial Sites on the World Heritage List". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea. 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ "S. Korea and Japan debate comments about being "forced to work"". The Hankyoreh. 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- ↑ "Japan:"Forced to Work"Isn't"Forced Labor"". SNA Japan. 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- ↑ "GUNKANJIMA(HASHIMA)". Nagasaki City. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Nagasaki Travel: Gunkanjima (Battleship Island), Japan guide, May 28, 2009, retrieved 2010-11-18

- 1 2 http://www.theverge.com/2012/11/15/3648540/skyfall-bond-villain-hashima-abandoned-island The chilling history behind the abandoned island in 'Skyfall' Accessed 2016-09-09

- ↑ "Centro de la imagem" (PDF). MX: Conaculta. 2009.

- ↑ "Episode One: The Bodies Left Behind" (Episode guide). Life After People. The History Channel.

- ↑ Gakuran, Michael. "Gunkanjima: Ruins of a Forbidden Island". Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ↑ 400 Aniversario México-Japón, JP: Mexican embassy, 2010-11-02

- ↑ Sony's Action Cam on RC Helicopter filming 軍艦島 (Gunkanjima / battleship island), YouTube, Sony, 2013-04-12

- ↑ dingra on Jul 2, 2013. "Google Maps Updated with 'Skyfall' Island Japan Terrain". HotHardware. Retrieved 2013-10-15.

- ↑ http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interest/2014-11-06/get-a-closer-look-at-the-attack-on-titan-live-action-films-setting/.80756

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hashima (Nagasaki). |

- Documentary of former resident revisiting the island on YouTube

- Studies of the Modern Buildings on Gunkajima 1916-1974 (1986)

Coordinates: 32°37′40″N 129°44′18″E / 32.62778°N 129.73833°E