Gun laws in the Czech Republic

| Gun laws by country |

|---|

Gun politics in the Czech Republic incorporates the political and regulatory aspects of firearms usage in the country. Policy in the Czech Republic is in many respects less restrictive than elsewhere in the European Union (see Gun politics in the European Union).

A gun in the Czech Republic is available to anybody subject to acquiring a shall issue firearms license first. Gun licenses may be obtained in a way very similar to a driving license - by passing a gun proficiency exam, medical examination and having a clean criminal record. Unlike in most other European countries, the Czech gun legislation also permits a citizen to carry a concealed weapon for self-defense. Most Czech gun owners possess their firearms for self-defense, with hunting and sport shooting being less common.[4]

The permissive politics have a very long tradition, with the term pistol originating in 15th-century Czech language.[5] The Czech lands have been the manufacturing center (including weapons industry) of Central Europe for over two centuries.[6] Firearms possession was severely restricted during German occupation and subsequent communist dictatorship, with ownership rates gradually rising ever since 1989 Velvet Revolution. Today the Czech Republic is home to arms manufacturers that include Česká zbrojovka Uherský Brod and Sellier & Bellot.

History

The Czech Crown lands witnessed one of the earliest mass uses of firearms, in the early 1420s and 1430s by the Hussites who are even today revered as national heroes. Žižka's use of guns, which had previously been used only during sieges of towns, as a field artillery in the Battle of Kutná Hora was first such recorded utilization.[7] Use of firearms, together with the wagon fort, was one of the key features of Hussite war strategy, which defeated five crusades, launched against the reformation revolt. The word used for one of the guns used by the Hussites, Czech: píšťala, later found its way through German and French into English as the term pistol.[5] Another gun used by the Hussites, the Czech: houfnice, gave rise to the English term, "howitzer".[8][9][10]

After the establishment of Czechoslovakia in 1918, the country adopted the existing Austrian gun law of 1852. The law was liberal, allowing citizens to own the guns without any formalities, with restrictions applying only regarding their number. However, carrying the gun was allowed only to the holders of a firearms license. Only a "harmless person" (trusted person with no criminal record) could get a firearms license. There was also a list of restricted firearms, such as terzerols, air guns and other weapons considered as "insidious". Distinctly more restrictive gun law was prepared in 1938, when the state was endangered by Nazi Germany and its fifth column (Nazis among German minority) but never came to use due to occupation of the country.[11]

Gun ownership was seriously restricted during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia: at first, all weapons were seized, including the duty-guns of police. Later the Nazis allowed limited armament of the police and governmental troops but forbade private gun ownership (except for hunting) and imposed very harsh punishments including the death penalty. Following the defeat of Germany in May 1945, the more liberal gun law was officially reintroduced. But in reality the government sought to reduce the amount of weapons which were among people as the result of the war. For Germans and suspected collaborators, gun ownership was forbidden.[11]

The situation changed again after the communist coup d'état of 1948. Although the law allowed for some restricted gun ownership, in reality the authorities were instructed about which groups of people would be allowed to own guns. In 1962 a secret directive was adopted, listing the names of persons deemed loyal enough to be allowed to own guns. Another more liberal law was introduced in 1983, but gun ownership remained relatively restricted. Access to guns for sporting purposes was easier (sport shooting was encouraged and supported by the state via Svazarm) and the rules for hunting shotgun ownership were relatively permissive.[11]

The new enactment of 1995, after the Velvet Revolution, meant a return to the more liberal times of the First Czechoslovak Republic. Accession to EU required a new law compliant with the European Firearms Regulation, which was passed in 2002. The law remained very liberal despite introducing more regulation.[11]

Current law

| License category | Age | Possession and ownership of firearm category | Ammunition restriction | Carrying | Note | No. (2012)[4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A - Firearm collection | 21 | A (subject to may-issue exemption by police) B (subject to shall-issue permit) C (subject to later registration) |

3 pcs or 1 smallest production package of the same type, caliber & brand [12] | No carry | In case of ownership of any A category firearm, the person must allow access for inspection of its safe storage to police officers.[13] | 82,572 |

| B - Sport shooting | 18 15 for members of a shooting club |

B (shall-issue permit) C (later registration) |

None | Transport only (concealed, in a manner excluding immediate use) |

134,546 | |

| C - Hunting | 18 16 for pupils at schools with hunting curriculum |

B (shall-issue permit) C (later registration) |

None | Transport only (open/concealed, in a manner excluding immediate use) |

Subject to exemption by police, may use also night-vision (A category accessory)[14] | 105,274 |

| D - Exercise of profession | 21 18 for pupils at schools conducting education on firearms or ammunition manufacturing |

A, B, C (possession only, firearm remains in the ownership of the employer) |

Only ammunition for the firearm in possession (no restriction on quantity). | Concealed carry (up to 2 guns ready for immediate use) Open carry for members of Municipal Police, Czech National Bank's security while in duty |

62,889 | |

| E - Self-defense | 21 | B (shall-issue permit) C (later registration) |

Only ammunition for the firearm owned (no restriction on quantity). | Concealed carry (up to 2 guns ready for immediate use) |

230,648 | |

| F - Pyrotechnical survey | 21 | None | N/A | N/A | May conduct pyrotechnical survey and deactivate munitions. | ? |

| Firearms Act | |

|---|---|

| Act on Firearms and Ammunition | |

| Citation | No. 119/2002 Coll. |

| Enacted by | Czech Parliament |

| Date enacted | 9 April 2002 |

| Date commenced | 1 January 2003 |

| Introduced by | Miloš Zeman's Government |

| Related legislation | |

| Regulation of Ministry of Interior No. 115/2014 Coll., on Execution of Certain Sections of Firearms and Ammunition Act (Firearms Regulation) | |

| Status: In force | |

There is no constitutional right to possess firearms in the Czech Republic. According to a 1999 decision of the Czech Constitutional court, the right to possess firearm is not a basic human right and it may not be derived from the right to own property guaranteed by the Art. 11(1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms.[15]

The right to have a gun license issued is provided for in the Act No. 119/2002 Coll.[16] Subject to fulfillment of the act's conditions, anyone is entitled to have the license issued and may then obtain a firearm.[17][18] Holders of D (exercise of profession) and E (self-defense) licenses, which are also shall-issue, may also freely carry a concealed firearm.[19]

Categories of licenses

There are six categories of gun license; however, these should not be mistaken with the categories for guns.[20]

- A - Firearm collection

- B - Sport shooting

- C - Hunting

- D - Exercise of a profession

- E - Self-defense

- F - Pyrotechnical survey

Obtaining a license

An applicant applies for a gun license at the police. If the conditions of age, qualification, health clearance, criminal integrity and personal reliability are met and a fee of 700 CZK per category is paid, the license shall be issued in 30 days.[21] The license must be renewed every ten years[18] (no need to undergo qualification exam if the application is filed at least 2 months before termination of the previous license; health clearance still necessary[22]).

Age

To obtain a B or C category license, the applicant must be at least 18 years old. Under special circumstances, the applicant need only be 15 if a member of a sporting club, or 16 if taught hunting in schools with such a curriculum. To obtain an A, D or E category license, the applicant must be 21.[23]

Qualification

Obtaining the license requires passing a theoretical and practical exam.

- Theoretical exam: The theoretical exam consists of a written test of 30 multiple choice questions (Created and distributed by the Ministry of the Interior) with a maximum of 79 points possible. To pass the written exam, 67 points are needed for category A, 71 for category B or C, and 74 for category D or E.[24] The test deals with the following issues:

- Practical exam

- Safe handling:[29] this comprises:

- Touching the trigger, pointing in different than appointed safe direction or trying to field strip loaded gun (dummy round is used) results in exam's fail. Depending on the categories of licenses sought, the applicants may be asked to show their ability of safe manipulation on multiple firearms (typically CZ 75 and/or CZ 82 pistol, bolt-action CZ 452 rifle and a double-barreled shotgun).[33]

- Shooting test,[34] which requires specific scores dependent on the category of license applied for:

- For the B and C category license it is 25m on rifle target (A4 sheet sized) with 4 out of 5 rounds hitting the target sheet shooting from a rifle (2 out of five for A category). .22 Long Rifle chambered rifle is used.[35]

- For the C category license, the applicant must also successfully hit the rifle target from the distance of 25m shooting from a shotgun, 3 out of 4 rounds must hit the target (at least partially).[36]

- For the E category license, the applicant must successfully hit the international pistol target 50/20 (50 cm x 50 cm) from a distance of 10m (15m for D category license) shooting from a pistol, 4 out of 5 rounds must hit the sheet (2 out of 5 for A category).[37]

- In each of the cases above, the actual score is irrelevant, only the projectiles have to hit the target sheet within the circles.[38] Also in each case, the applicant is allowed 3 test shots to familiarize with the particular firearm used for the test. The shotgun is an exception to this, where only one round is allowed as a test shot.[39]

A person can obtain more or all of the categories at once. But the set of categories needs to be known before the exam and highest score needs to be met.[40] Typically, people obtain E and B category because these two categories provides the best versatility (almost any firearm can be owned and carried concealed). The D category is required by the law for the members of the municipal police (members of the state police do not need license for on duty firearms) and does not itself permit private gun ownership (unless the person obtains also other license category).[41]

Health clearance

Applicant (license holder) must be cleared by his general practitioner as being fit to possess, carry and use a firearm. The health check includes probes into the applicant's anamnesis and a complete physical screening (including eyesight, hearing, balance). The doctor may request examination by a specialist in case he deems it necessary to exclude illnesses or handicaps stated in the respective governmental regulation. Specialist medical examination is obligatory in case of illnesses and handicaps that restrict the ability to drive a car.[42]

Governmental Regulation No. 493/2002 Coll.[43] divides the listed illnesses and handicaps into four groups, covering various issues from psychological and psychiatrical to eyesight and hearing (for example, the applicant must be able to hear casual speech over distance of 6 meters to be cleared for the E category). Generally, the regulation is more permissive when it comes to the license categories A and B, and more strict with view to the other categories, listing which illnesses and handicaps may curtail or outright prevent positive clearance by the general practitioner.[44] The outcome of the medical examination may be either full clearance, denial, or conditional clearance that lists obligatory health accessories (glasses, hearing aid, etc.) or sets obligatory escort when armed (e.g. B - sport shooters with minor psychological issues, or with addiction habits cured more than three years prior to the health check).[45]

Criminal integrity

The enactment specifies the amount of time which must elapse after a person is released from prison for serving time for particular groups of crimes. Ex-convicts punished for committing selected crimes, such as public endangerment, or participation in organized crime group or murder, if sentenced to more than 12 years imprisonment, may never fulfill this condition.[46] There is a central registry of criminal offenses in the Czech Republic. The criminal integrity is reviewed notwithstanding any possible expungement of the records for other purposes.[47]

- After being conditionally discharged, the criminal integrity is regained after the probation period ends or in 3 years in special cases

- After serving less than 2 years or being sentenced to different kind of punishment than imprisonment, the criminal integrity is regained after 5 years

- After serving 2 to 5 years, the criminal integrity is regained after 10 years

- After serving 5 to 12 years, the criminal integrity is regained after 20 years

- After serving more than 12 years (for defined crimes, such as murder, treason etc.) the criminal integrity is never regained.

Police may order temporary seizure of firearm license and firearms in case that the holder is charged with any intentional crime, or a negligent crime connected with breach of duties relating to possession, carrying or use of firearms or ammunition.[48]

Personal reliability

A person who verifiably excessively drinks alcohol or uses illegal drugs, as well who was repeatedly found guilty of specified misdemeanors (e.g. related to firearms, DUI, public order, etc.) in the preceding three years, is considered unreliable for the purposes of issuing a gun license. The police has the right to inquire information regarding these issues also from municipal authorities (misdemeanors are dealt with by municipal authorities and there is no central registry related to them).[49]

Losing reliability is caused by:

- Commiting a crime and being conditionally discharged, until the probation period ends.

- Excessive use of alcohol or addictive substances

- Commiting multiple misdemeanors from specific segments of the law (Regarding Firearms, Explosives, Driving under influence, Czech Republic defense, public order, property and illegal hunting/fishing). Only one transgression in last 3 years is tolerated. Other types of misdemeanors do not count to personal reliability criteria.

Police may order temporary seizure of firearm license and firearms in case that administrative proceedings against the holder are initiated for committing selected misdemeanors (e.g. carrying while intoxicated, refusing to undergo intoxication test while armed, shooting outside licensed range unless in self-defense).[48]

Obtaining of a license by a foreigner

The law distinguishes foreigners according to their country of origin. For selected foreigners, a license is shall-issue as same as for Czech citizens, while for others it is a may-issue.[50]

|

|

Foreign born residents are treated equally in the eye of Czech law (see above), but proof of a lack of criminal record in their country of origin must be provided;[51] persons having residence also in another EU country must provide documentation showing that they are allowed to own a firearm therein.[52] All the documents must be translated into Czech language by a sworn translator.[51]

Foreigners with registered place of residence in the Czech Republic may purchase firearms after obtaining corresponding licenses and permits; persons having residence also in another EU country must provide documentation showing that they are allowed to own such a firearm therein in order to be granted a permit to purchase a B category gun.[53]

The written test as well as the practical exam has to be taken in the Czech language. Until 31 December 2011, test-takers were allowed to use a sworn interpreter/translator, but this has since been forbidden.[54][55]

Categories of guns

Under the current gun law, guns, ammunition and some accessories are divided into four categories (these should not be mistaken with categories of licenses):

A - Restricted firearms and accessories

- Includes full automatic firearms, military firearms and ammunition not inspected and marked for civilian use, some types of ammunition such as armor-piercing and incendiary ammunition, night vision scopes, suppressors and gun mounted laser pointers. The use of hollow point ammunition in pistols is also restricted, however, hollow points are legal to purchase for rifles and pistol carbines.[59]

B - Guns requiring permit

- Includes semi automatic and single or multiple shot handguns, revolvers, semi automatic rifles and shotguns with magazine capacity over 3 rounds or with a detachable magazine, semi automatic "military" style rifles, rim-fire firearms under 280 mm of length and all shotguns under 600 mm of length, flare guns with caliber larger than 16mm.[60]

C - Guns requiring registration

- Includes single shot or bolt action rifles longer than 280 mm, shotguns, semi-automatic rifles not included in B, air rifles with muzzle energy over 16 J and black powder repeaters.[61]

D - Guns available to adults above 18

- Includes air guns (muzzle energy up to 16 J), mechanical guns (with kinetic energy from 150 N), replicas (black powder up to two shots - e.g. not black powder revolvers), airsoft guns, vintage firearms (manufactured prior to 1890), expansion guns and .22 CB cap (muzzle energy up to 7.5 J).[62]

A person must obtain the Gun License (Zbrojní průkaz) to be allowed to own gun of categories A, B and C.[63] To own a gun in the D category only the age of 18 is required.[64] A, B and C category weapon has to be registered within 10 working day with the police after it is bought.[65]

Obtaining firearms

Each of the A, B, C and E categories of gun license allows the person to buy a B or C category of gun. Holders of an A category license may, after being granted may-issue exemption by the police, also purchase an A category firearm; holders of D category may possess and carry any category of firearm (which remains the property of the employer).[66]

In case of B license the person is allowed to use their guns at shooting ranges. The C license is required by other laws for hunting. The E license allows the person to own a gun for self-defense purpose and carry the concealed weapon. All guns need to be registered with the police in 10 working days after buying except for the D category.[66]

- To obtain a gun from the A category (typically a full-automatic or select-fire firearm), the person must ask for a may-issue "exemption" from the police and demonstrate a specific reason why they want such a weapon.

- For private physical persons, the only acceptable reason is collecting;[67]

- for physical or legal persons having an armament license (this is a completely different certificate than the gun license) for professional purposes the acceptable reasons include providing security for dangerous or valuable shipments or VIP objects, manufacturing or testing of firearms, providing training in use of A category firearms, or filming in case that the firearm is adjusted for use of dummy rounds.[67]

- The B category of guns (typically any semi-automatic firearm) requires permission from the police. Before buying the gun the person must visit the police and fill in the "permit to buy, own and carry" form for the particular weapon (depending on the police department, usually caliber and type of weapon is required).

- As a formality, a person must state a justifiable reason for purchasing a B category firearm, which include collecting, sporting, hunting or cultural activity, conducting business with firearms and ammunition, providing security, exercise of profession and self-defense.[68] The police will issue the permit in up to 30 days (usually immediately) and the permit is shall-issue if the applicant has a valid gun license (and fulfills all of its requirements, e.g. clean criminal record); the purchase permit is valid for 12 months.[69]

- The C category of guns can be bought at a gun shop after presenting the gun license. However, the gun needs to be registered later at the police.[71]

There is no limit in the law on number of owned guns. The law specifies safe storage requirements for those owning more than two weapons or more than 500 rounds of ammunition. The safe storage requirements are further exacerbated for those owning more than 10 and more than 20 firearms.[70]

Possession of a firearm that does not belong to category D without a gun license (as well as sale, manufacturing, procurment, etc.) is a criminal offense which carries a penalty of up to two years imprisonment (up to eight years in defined cases).[72]

Shooting ranges

Firearm owners are allowed to practice only at licensed shooting ranges and may otherwise use the firearm only in case of self-defense, or when permitted by other laws (e.g. hunting).[73] As of 2014, there are almost two hundred places opened for the public.[74] Any adult can visit such a range and shoot from available weapons, without restrictions or permits. A person without a gun license has to be supervised (if younger than 18, then by a person at least 21 years old who has been a holder of a gun license for at least 3 years).[75]

Carrying a firearm

Holders of different categories of firearms licenses have different possibility of carrying their firearms. In general, it is prohibited to carry firearms to court buildings (they may be left for safe keeping with the judicial guard upon entry before passing through metal detector), at demonstrations or mass meetings.[76] It is also generally considered irresponsible to take guns to clubs or bars even though it is not explicitly prohibited by law. Carrying a gun while intoxicated is, however, illegal and can lead to heavy fines and losing the gun license,[77] with police frequently conducting intoxication tests of open-carrying hunters.[78] Carrying guns in schools and campuses is not prohibited by law and there are no so called "gun-free zones".[16]

The Czech Republic is a relatively safe country: Prague, with the highest crime rate in the country, still ranks as one of the safest capitals in the European Union.[79] Considering the number of E category licenses issued, there are about 200,000 people who could potentially carry a firearm; however, it is not clear how many regularly do so.[80]

License types

- No carry: Holders of A license (collection purposes) may only obtain and possess firearms (also those falling into the A - restricted guns category, subject to being granted a may-issue permit) and are not allowed to carry them.[81]

- Transport only: Holders of B (sport shooting) license may only transport their firearms to and from the areas designated for sport shooting. The firearms must be transported in a closed container and in a manner that excludes their immediate use.[82]

- Meanwhile, holders of C (hunting) license may too transport their firearms only to and from the areas designated for hunting in a manner that excludes their immediate use. In case that they use public transportation, the firearm must also be transported in a closed container, otherwise it may be transported (carried unloaded) openly.[82]

- Concealed carry: Holders of category D (exercise of profession) and E (self-defense) license may carry up to two firearms ready for immediate use (bullet-in-chamber). The firearms must be carried in concealed manner.[83] The requirement of concealed carry applies also for D holders of restricted firearms (e.g. private security with fully automatic firearms).[84]

- Open carry: Only the members of Municipal Police and of the Czech National Bank's security, as holders of D (exercise of profession) license, may carry their firearms openly while on duty.[85] Members of state police, prison service and other governmental security agencies do not need any gun license and are permitted/required by other laws to open or concealed carry while on duty.[86]

- Open carry may be allowed by police for special occasions, such as gun shows, war reenactments or liberation day celebrations; these are however technically referred to as "public display of firearm" rather than "carrying". Each person that wishes to "display" firearm must submit a request detailing the given occasion, firearm(s), their protection against theft, etc.[87] Also, during these occasion the police often conducts inspections of gun holders regarding the respective paperwork and intoxication testing.[88]

Ammunition restrictions

All of the high-penetrating (armor-piercing) and hollow-point ammunition is classified as category A (see above).[59] The alternative to a hollow point ammunition was Federal EFMJ, which has been classified into the arms group A in mid 2009, effectively outlawing it. Therefore, only full metal jacket or soft-nosed semi-jacketed rounds and or just unjacketed bullets (lead only) are allowed. Generally, no ammunition with higher wounding potential is allowed.[89]

There is currently no restriction on caliber size and no restriction on magazine capacity. However, special safe storage requirements apply for those having more than 500, 10,000 and 20,000 bullets.[70]

Armament licences

Gun licences equivalent for legal persons, such as shooting ranges or private security companies. Divided into 11 categories.

- A - Development or manufacturing of firearms/ammunition

- B - Repairs, modifications or deactivation of firearms/ammunition

- C - Firearms/ammunition buying and selling

- D - Lending and safekeeping of firearms/ammunition

- E - Deactivation or destruction of weapons/ammunition

- F - Training in handling and using firearms/ammunition

- G - Providing security for persons/property.

- H - Cultural, sports and hobby shooting activities.

- I - Collecting and displaying firearms/ammunition

- J - Securing tasks defined by special legal enactments.

- K - Pyrotechnical Survey (Replaces F category gun licence in 2017)

Self defense with firearms

There are no specific legal provisions covering self-defense by a civilian using a firearm. The general provision regarding criminal aspects of self-defense are contained in the Section 29 (Necessary self defense) of the Criminal Code.[90] General provisions regarding civil liability in respect of self-defense are contained in the Section 14 of the Civil Code.[91]

In general, Czech penal theory recognizes certain classes of circumstances where criminal & civil liability will be excluded in respect of actions which would normally attract a criminal penalty. These include "utmost necessity", "necessary self defense" and other cases involving "eligible use of a gun".[92]

Utmost necessity

Utmost necessity may be invoked where an interest protected by the Criminal Code (such as right to property or right to life) is endangered. An example of necessity would be a defense against a raging dog (unless the dog was directly sent by the owner, which would be case of necessary defense). The necessity may be invoked only in case of imminent danger and only if there is no other way of avoiding it (subsidiarity), such as locking oneself behind a fence or calling the police. Also, the consequence of the necessity must be less serious than the consequence of the endangering act (proportionality).[92]

Necessity is excluded in cases where:[92]

- the consequence of necessity is equal to or greater than that of endangerment

- the necessity continues after the endangerment has ceased

- the endangerment could have been deflected in other ways, i.e. with less serious consequences

- there is a duty to withstand the endangerment (a special situation which does not cover civilians)

Necessary self defense

The basis of necessary self-defense is deflection of an imminent or ongoing attack against an interest covered by the Criminal Code (such as right to property or right to life) by performing an action which would otherwise be punishable (such as use of a firearm against the other person). The imminent part means that a party is evidently and immediately threatened, it is not necessary to wait for the attacker to start the attack, especially if he is known for his aggressiveness. (That, however, is not the case if the attack is being prepared, but not imminent). The necessary self-defense may also be enacted when defending someone else's interest (i.e. defending their person or their property) as long as the same requirements are met. However, defending against a provoked attack is not considered "necessary self defense".[92]

There is no requirement of subsidiarity: in this respect "necessary self defense" differs from "utmost necessity". The main limitation is that the defense may not be manifestly disproportionate to the manner of the attack. The manner of the attack is not the same as its intensity, which is only a part of it. For example, "intensity" covers whether the attack is committed by a single attacker or a group, with or without a gun, and the relative strength of the attacker and the party attacked, etc. But the manner also includes future imminent dangers, such as the possibility that single attacker might imminently be joined by others.[92]

As regards proportionality, the law states that a self-defense may not be manifestly disproportionate. It is evident, that for a self-defense to be successful, it has to be performed on a level exceeding the attack. Unlike in case of necessity, the consequence of necessary self-defense may be more serious than consequence of the attack. The defense may not be restricted to a passive one, it can also be active. It is not the outcome of the incident but the sequence of actions at its beginning which determines who is to be deemed the attacker, and who is the party attacked.[92]

There are two main excesses, which are not recognized as necessary self-defense:[92]

- defense, which continues after the attack is over, i.e. when a robber is running away without any loot (excess in time)

- defense, which is manifestly disproportionate, such as shooting children who steal apples from a tree, or shooting a perpetrator who has passed over a fence, without giving indication of further malevolent or criminal intentions (excess in intensity)

Eligible use of a gun

Eligible use of a gun is addressed in special enactments dealing with police, secret security service, prison guards etc.[92] Thus for example a policeman may, under specified conditions, shoot on an escaping suspect, a privilege which an armed civilian does not have.[86]

General tendencies

It is acceptable to defend from a violent attack anywhere on the street especially when a person is attacked with a knife or another deadly weapon. Shooting an unarmed attacker also occurs and becomes sometimes a subject of controversy. In general, each case is investigated in great detail before being eventually dismissed as a legitimate self-defense.[94] The defense is judged according to the subjective and objective perception of the defender during the time of the imminent or ongoing attack, and not according to the view of persons who are judging it ex post.[95]

The American style Castle Doctrine is also not applied however it is usually considered acceptable to defend from a violent home invasion with a firearm. In 2014, an amendment of laws concerning self-defense was proposed with the aim of giving greater leeway to defenders, especially in cases when they would not normally meet the bar for legitimate self-defense under the current legislation, but face extraordinary circumstances, such as confusion as a consequence of the attack, or when facing home invasion.[94]

Although there is no stand-your-ground law, the fact that necessary defense (unlike utmost necessity) is not subject to subsidiarity means that there is also no duty to retreat.[96] The mere fact that a defender uses a weapon against unarmed attacker does not mean that the defense is disproportionate (and thus not legitimate) to the manner of the attack[97] and the proportionality of defense does not depend on the relative effectiveness of the defender's weapon compared to the intensity of the attack, but on the manner in which the weapon is used[98] (aiming at leg, i.e. intended non-deadly defense, may be proportionate where aiming at chest may be manifestly disproportionate, notwithstanding if the slug hits a leg artery and the attacker bleeds to death[99]).

The fact that a person prepares a weapon in order to defend themselves against expected attack does not preclude the defense from being legitimate[100] and, according to courts, it may not be expected from a defender to wait and rely on chance that a damage which is, both objectively and in the defender's subjective understanding, threatened to happen, will not take place. The defender may use proportionate accessible means in order to prevent an imminent attack and disarm the attacker.[99]

A number of successful defensive uses of firearms or other weapon is being cleared as legitimate self-defense by authorities every year without raising wider public concern, including for example a 2014 shooting of an attacker by a bartender in Hořovice,[101] or a 2014 shooting of an aggressive burglar in a garage by homeowner in Čimice.[102] However, some cases become rather notable, such as:

- In 1991 a group of white supremacy skinheads attacked a couple on a street in Prague after a man called on them to cease nazi salutes. The commotion was witnessed by Pavel Opočenský, a former anti-communist dissident, émigré and famous sculptor, who immediately rushed to help the victims. During the fight, Opočenský used his hunting knife and killed a 17-year-old metal-bar-wielding skinhead. Opočenský was first charged with murder and spent 2 months in a remand prison. He was released from remand prison after the charges were diminished to intentional infliction of bodily harm resulting in death (i.e. manslaughter). He was first convicted by the Municipal Court in Prague and conditionally sentenced to 2 years imprisonment with 4 years probation period. After a lengthy legal proceedings in which higher court repeatedly overturned the Municipal Court's convictions and ordered retrial, Opočenský's actions were finally cleared as legitimate self-defense by the High Court in Prague's decision four and half years later. The trial attracted attention of WP skinheads who conducted various protests. A neo-nazi band Agrese 95 released a song titled "We shall go together and kill Opočenský."[103][104]

- In 2003, Slavoj Hašek was awaken by commotion from outside of his house. Hašek left his house with a shotgun and pursued a thief. After the thief got to his own car and drove it in the Hašek's direction, he shot and killed him. Hašek was sentenced to five years imprisonment with the High Court in Olomouc arguing that defense could not be legitimate, since the shot went through a side window rather than through the front windshield. Hašek was pardoned by the President Klaus shortly thereafter.[105]

- In 2004, a Ukrainian immigrant attempted to rape a university student from Russia in Prague. While the rapist was forcing himself on her, she managed to grab a knife from her purse and stabbed him directly in the heart, instantly killing him. The police closed the case as a legitimate self-defense 3 months later with no charges being brought.[106]

- In 2006 a private security guard with a pistol pursued on foot two men whom he believed tried to steal scrap metal. The men climbed on a railway embankment and started throwing rocks down at the guard who thereafter shot ten rounds in their direction, mortally wounding one of them in the head. The guard was first convicted of murder by the Municipal Court in Prague and given a sentence of 7 years imprisonment. The decision was changed by the High Court in Prague to conviction of intentional infliction of bodily harm resulting in death (i.e. manslaughter) and a sentence of five years imprisonment. The guard was finally exonerated by the Supreme Court in Brno which considered his action legitimate self-defense, noting that defense must be clearly more intensive than attack in order to be successful, and that the stones and bricks being thrown presented grave danger to the man's life.[107]

- In 2009, a security system at a scrap metal yard, which had been repeatedly burglarized, went off. The yard's owner was at the time on a hunt close to the yard and drove directly to it. A group of burglars jumped into their car and attempted to drive away. The owner used his shotgun and attempted to shoot the car's tires, hitting and wounding two of its occupants. He was sentenced to 6 years imprisonment for intentional infliction of bodily harm, a sentence that was confirmed also on appeal. The owner received full presidential pardon.[108]

- In 2010, a student from Azerbaijan was verbally attacked by a group of other foreigners in a bar in Prague. The student left the bar and proceeded to his friend's car, being followed by the group who continued to verbally attack him and his family and stating that "the issue needs to be solved immediately". The student recovered a knife from the car and took a stand. Thereafter one of the foreigners started punching him. The student stabbed one of the four attackers and then engaged in fight with another, whom he stabbed in the leg and who bled to death. The Municipal Court in Prague convicted the Azerbaijanian student of intentional infliction of bodily harm with excusable motive and sentenced him to two year in prison. The decision was overturned by the High Court in Prague who considered the death an outcome of legitimate self-defense. The Supreme State Attorney mounted an extraordinary appeal to the Supreme Court, which however confirmed the acquittal, noting that the verbal abuse continued even after the victim got into the car and he could thus legitimately perceive it as an ongoing attack. The Supreme Court also refused the Municipal Court's previous line of argumentation that the victim could have easily left the place once in the car (as there is no duty to retreat under Czech law) as well as its reasoning that the threat did not reach such an intensity as to justify a lethal defense.[99][109]

- In 2012, two brothers in their early 20s, one of them armed with a knife, attacked a 63-year-old man in a town in the Northern Bohemian borderland. He shot both attackers with his legally owned pistol, killing one of them. The police closed the case as legitimate self-defense six months later and brought charges against the surviving attacker.[110]

Popularity of guns

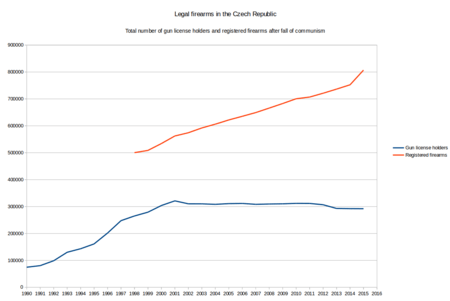

Despite the relatively liberal gun laws, guns are not especially popular in the Czech Republic with only 3% of population having gun licenses. Nevertheless, sport shooting is the third most popular sport after football and hockey[56] and with 2,3% of population having self-defense licenses, the country had higher ratio of people with concealed carry permits than USA up to 2008. In 2015, there were 292,022 licenses and 806,895 registered firearms[3] (for the 10,5 million population). In the long term number of licenses slightly decreases while number of registered guns keeps growing.[2]

Unprecedented rise in gun sales took place in 2015. While the average annual rise in the number of registered firearms amounted to 14,500 guns between 2006 and 2014, there were 54,508 new registered firearms in 2015 alone.[3] Following the culmination of European migrant crisis, November 2015 Paris attacks and an EU proposal to ban selected firearms, there was also huge rise in number of qualification exam applications which by November tripled compared to the monthly average of Q1 2015.[111]

The Czech Republic is home to many firearms manufacturers including Česká Zbrojovka. Famous models of handguns such as CZ 75 are very popular among Czechs. Czechs also favour various types of Glocks and 1911 clones. Semi-automatic rifles made by Czech manufacturers, especially vz. 58 and AR 15, are also very popular especially among Czech competition shooters or hunters. There are relatively fewer revolvers, mostly from US manufacturers such as Smith & Wesson and Colt, or Czech producers ALFA and Kora.[56]

Incidents and gun crimes

In 2005, there were 5,317 misdemeanors and 924 criminal offenses committed with firearms[113] compared to 5428 misdemeanors and 836 criminal acts in 2007.[114]

It is generally not common for licensed gun owners to commit violent crimes with their guns, and most of the gun crimes are committed with illegal weapons that are beyond the control of the law.[115] The number of murders committed with legally owned guns reached its peak in 2000, when 20 people were murdered. There were 16 murders committed with legally owned guns in 2003, 17 in 2007 and 2 in 2010. The majority of them are committed during family quarrels, with only a minimum being premeditated.[56]

Occasionally, crimes with legally owned guns do happen. The most notable examples include:

- 2001 shooting of three policemen who were called by a woman claiming she was being attacked by her husband, František Jůza. On the scene, the policemen were negotiating with the husband who was threatening to commit suicide with his legally owned .38 revolver. When the situation seemed about to be peacefully solved, the hysteric wife ran into the room. Jůza thereafter shot three policemen (two mortally) and committed suicide.[116]

- Viktor Kalivoda, a.k.a. "Forest Killer", who was planning to go on a killing spree in Prague Metro in 2005. As part of his preparation, the former policeman randomly murdered two hikers in a forest and another person four days later in another forest about 200 km from the first killing with his legally owned Glock. Police captured Kalivoda a week later, thus preventing further murders.[117] Kalivoda was sentenced to life imprisonment. While in prison, he committed suicide in 2010.[118] As a former policeman, Kalivoda had passed a difficult psychological evaluation as part of the police selection procedure.[119]

- 2008 shooting at former PM's birthday party, which occurred at a party of a Czech politician and former Prime Minister Jiří Paroubek, where his acquaintance Bohumír Ďuričko shot Václav Kočka junior, the son of a Prague businessman, with his legally carried gun after a short quarrel. Ďuričko later claimed he was acting in self-defense after Kočka attacked his pregnant girlfriend. According to the eyewitness testimony, it seemed highly unlikely. In April 2009, Bohumír Ďuričko was found guilty of murder and sentenced to 12-and-a-half years in prison.[120]

- 2013 Raškovice shooting, where a 31-year-old schoolteacher invaded the house of one of his students, aged 17, with whom he had allegedly been previously intimately involved, and shot the student and her grandparents, using various legally owned firearms (with caliber .22, .38 and .45). The perpetrator had further 10 firearms at home and over 10,000 rounds of ammunition; he had passed psychological evaluation ordered by his general practitioner before getting gun license. The perpetrator was sentenced to 27 years imprisonment.[121][122][123]

- 2015 Uherský Brod shooting, the largest mass shooting in the country's peacetime history, in which a deranged individual murdered 8 people. He was a holder of a gun license and legally owned both of the guns he used in the shooting. Previously, he and his wife committed misdemeanors against public order, which would've allowed police to revoke his license.[124]

General attitudes to guns and efforts to tighten the law

| “ |

Those who [legally] carry guns are the most polite citizens. We don't take part in brawls, we don't quarrel on the street, we don't drink & drive even with the lowest amount of alcohol in blood, because so little may be sufficient to lose the gun license and being forced to sell the gun. |

” |

| — Stanislav Gibson, director of Lex, a Czech firearms owners' lobby association[56] | ||

The gun law in the Czech Republic is quite liberal. It is mostly caused by the fact that after the fall of communist regime people wanted to regain their rights to keep and bear arms and these needs resulted in passing quite a liberal legislation in 1996, which surpassed the previous restrictive communist enactment. The law became widely accepted and led to quite massive civilian arming. Especially many businessmen felt the actual need to obtain a firearm because the times shortly after the Velvet Revolution are known for the rise in organized crime often related to the economic transformation in the early 1990s.[125]

Due to falling crime rates fewer people felt the need to carry a firearm for protection after 2000s. This trend however changed in 2015 following the European migrant crisis and November 2015 Paris attacks. Gun advocacy groups argue that there is no point in banning guns because criminals will get guns no matter how tight the law is.[56] At the same time, however, the rules are deemed to be restrictive enough to prevent criminals from easily obtaining firearms, while allowing upstanding citizens to own them for personal protection. For example, in 2010, a Norwegian terrorist, incited by reports of British newspapers describing Prague as "being the most important transit site point for illicit weapons in Europe", found himself unable to obtain any in the country when preparing for the 2011 Norway attacks.[126][127][128] Similarly, a Polish terrorist obtained guns illegally in 1200 km distant Belgium, despite living mere 70 km from the Czech border.[129] Also the fact that Czech Republic has a strong tradition in firearms manufacturing and competition shooting contributes to generally moderate attitude to gun control.[56]

A sharp increase in regional gun ownership took place in 2011 after a number of attacks of Romani perpetrators against victims from the majority population, some of which were racially motivated. This arming was taking place especially in regions such as Šluknov Hook, where high crime rates are often attributed to people from Roma minority, and where majority population distrust police and authorities.[130] This local trend however didn't significantly influence long term statistics.[2]

Efforts to tighten the law usually arise after deadly incidents like those described above. Obligatory psychological testing for gun owners is a common subject of discussion, but it has always been rejected. Gun advocates point out that the nature of the tests and the parties responsible for them are not clear. It is also pointed out that it is unlikely that any psychological testing would reveal a potentially dangerous individual, because some famous killers in the past were members of the military or the law enforcement and passed very difficult psychological testing successfully.[119]

The law was last tightened in 2008 introducing for example stricter sanctions for carrying gun while intoxicated. Proposals to introduce mandatory psychological testing were not passed.[131] The efforts to tighten gun legislation are also unlikely to pass as about a fifth of members of the Czech Parliament are holders of gun license; some of them are believed to carry firearms also within the parliament grounds (parliamentarians are not required to pass gun check on entry unlike other staff or visitors).[132]

2014 European parliamentary elections

Generally, firearms possession is not a politicized issue that would be debated during Czech elections. The 2014 European Parliament election became an exception in connection with the Swedish European Commissioner Cecilia Malmström's initiative to introduce new common EU rules that would significantly restrict the possibilities of legally owning firearms.[133]

In connection with that, a Czech gun owners association asked the parties running in the elections in the Czech Republic whether they agree (1) that the citizens should have the right to own and carry firearms, (2) that the competence on deciding firearms issues should lay in the hands of the nation states and not be decided on the EU level, and (3) whether they support Malström's activity leading to the curbing of the right of upstanding citizens to own and carry firearms. Out of 39 parties running, 22 answered. The answers were almost unanimously positive to the first two questions and negative to the third one. Exception were only two fringe parties, the Greens - which, while supporting the right for gun ownership in its current form, also support further unification of rules on the European level and labeled the opposing reaction to Malström's proposal as premature, and the Pirates which support unification of the rules leading to less restrictions elsewhere, commenting that one may not cross the borders out of the Czech Republic legally even with a pepper spray. Other fringe parties at the same time voiced their intent to introduce American style castle doctrine or to arm the general population following the example of the Swiss militia.[134]

2015 European Commission "Gun Ban" proposal

The European Commission proposed a package of measures aimed to "make it more difficult to acquire firearms in the European Union" on 18 November 2015.[135] President Juncker introduced the aim of amending the European Firearms Directive as a Commission's reaction to a previous wave of Islamist terror attacks in several EU cities. The main aim of the Commission proposal rested in banning B7 firearms (and objects that look alike), even though no such firearm has previously been used during commitment of a terror attack in EU (of 31 terror attacks, 9 were committed with guns, the other 22 with explosives or other means (truck in Nice). Of these 9, 8 cases made use of either illegally smuggled or illegally refurbished defunct firearms. The one legal firearm used during 2015 Copenhagen shootings was stolen from an army guardsman.)[136]

The proposal, which became widely known as "EU Gun Ban", would in effect ban most legally owned firearms in the Czech Republic, was met with rejection:

- Government Resolution No. 428/2016 of 11 May 2016[137]

- The Government tasks the Prime Minister, the First Vice-Prime Minister for Economy and Minister of Finance, Minister of Interior, Minister of Defense, Minister of Industry and Trade, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Labor and Social Affairs to (1) conduct any and all procedural, political and diplomatic measures necessary to prevent adoption of such a proposal of European Directive, that would amend the Directive No. 91/477/EEC in a way which would excessively affect the rights of the citizens of the Czech Republic and which would have negative effect on internal order, defense capabilities and economical or labor situation in the Czech Republic and (2) enforce such changes to the proposal of directive that would amend the directive no. 91/477/EEC that will allow preservation of the current level of civil rights of citizens of the Czech Republic and which will prevent negative impact on internal order, defense capabilities and economical and labor situation in the Czech Republic.

- Resolution of Chamber of Deputies No. 668/2016 of 20 April 2016[138]

- The Chamber of Deputies (1) expresses disapproval with the European Commission proposal to limit the possibility of acquisition and possession of firearms that are held legally in line with national laws of EU Member States, (2) refuses European Commission's infringement into a well established system of control, evidence, acquisition and possession of firearms and ammunition laid down by the Czech law, (3) expresses support for establishment of any and all functional measures to combat illegal trade, acquisition, possession and other illegal manipulation with firearms, ammunition and explosives, (4) refuses European Commisssion's persecution of Member States and their citizens through unjustified tightening of legal firearms possession as a reaction to terror attacks in Paris and (5) recommends the Prime Minister to conduct any and all legal and diplomatic steps to prevent enactment of a directive that would disrupt the Czech legal order in the area of trade, control, acquisition and possession of firearms and thus inappropriately infringe into the rights of the citizens of the Czech Republic.

- Senate Resolution No. 401/2016 of 20 April 2016 [139]

- Senate (…) (2) points out that the Commission’s directive proposal should be primarily aimed at illegal acquisition and possession of firearms, their proper deactivation and illegal firearms trade, as it is illegal firearms that are used during terror attacks, not firearms possessed in line with law of Member States and thus (3) disagrees with measures proposed in the directive that would lead to limitation of legal firearms owners and to disruption of internal security of the Czech Republic without having any clear preventive or repressive impact on persons possessing firearms illegally; such measures are contrary to the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality (...)

- Joint Declaration of Ministers of the Interior of Visegrad Group of 19 January 2016[140]

- The Ministers are fully aware of the need to fight actively against terrorism. As regards the regulation of the possession of firearms, it is necessary to focus the adopted measures primarily on illegal firearms, not legally-held firearms. Illegal firearms represent a serious threat. Within the European Union, it is necessary to prevent infiltration of illegal firearms from the risk areas. It should be taken into account that bans on possession of certain types of firearms that are not, in fact, abused for terrorist acts can lead to negative consequences, especially to a transition of these firearms into the illegal sphere. The V4 states have profound historical experience with such implications.

Ministry of Interior published in May 2016 its Impact Assessment Analyses on the proposed revision of directive No. 91/477/EEC. According to the Ministry, the main impacts of the proposal, if passed, would be:[141]

- Risks to internal security: According to Czech Ministry of Interior, the main danger of the proposal rested in massive transfer of now legal firearms into illegality, with up to hundreds of thousands of legal firearms entering black market. While the original Commission proposal would affect 40.000 – 50.000 firearms legally possessed by Czech citizens, Dutch EU Council Presidency proposal of 4 April 2016 would affect some 400.000 legally owned firearms, i.e. making half of all Czech legally owned firearms illegal. The proposal as such is in direct contradiction with Ministry’s long-term objective of lowering of number of illegal firearms and of conducting effective supervision of firearm owners.

- Risk to defensive capabilities: Security forces are not changing armaments annually, and thus small arms manufacturers need civilians as key customers. Crippling of civilian firearms market would likely lead to end of firearms manufacturing in the Czech Republic. At the same time, familiarity with semi-automatic versions of army rifles by civilians is a clear defensive advantage in case these people need to be drafted to defend the country.

- Threat to national culture: The proposal would lead to permanent deactivation of firearms owned by collectors and museums, including army museums, even though there is no empirical data supporting need for such a measure.

- Rise of unemployment: The proposal would lead to cancellation of tens of thousands of work places in the Czech Republic alone.

- Impact on hunting: Semiautomatic rifles have been purposefully used for hunting in the Czech Republic since at least 1946 and they are especially effective and popular in curbing wild boar overpopulation that is responsible for large number of car accidents as well as damages to agriculture. Banning of these firearms would likely lead to increase of car accidents due to collisions with wild animals and consequent increase in number of injuries and fatalities.

- Impact on state budget: As Czech constitution does not allow confiscation without remuneration, the government would have to pay up to tens of billions Czech crowns (billions of Euros) as compensation for banned firearms. Meanwhile rise in unemployment would further impact budget income.

Other types of weapons

There is currently no regulation on other type of weapons such as knives, pepper sprays, batons or electrical paralyzers. These weapons can be freely bought and carried in concealed manner by anybody above 18.[142] Similarly as in the case of firearms, it is prohibited to carry these weapons to court buildings, demonstrations and mass meetings.[143] The Ministry of the Interior officially recommends carrying non-lethal weapons such as pepper sprays, paralyzers, or gas pistols as means of self-defense[142]

References and sources

- ↑ "http://gunlex.cz/domu/47-clanky/informace-lex/688-statistika-drzitelu-zbrojnich-prukazu-1990-2010" (in Czech). Gunlex. Retrieved 2013-08-31. External link in

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 "Gun license statistics between 2003 - 2012" (in Czech). Gunlex. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- 1 2 3 "V ČR loni mělo zbrojní průkaz 292.000 lidí, jejich počet klesl" (in Czech). ČTK. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- 1 2 Eurobarometer, Directorate General for Communication (2013), Flash Barometer 383: Firearms in the European Union - Report (PDF), Brusselss, retrieved October 2013 Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 Karel Titz (1922). Ohlasy husitského válečnictví v Evropě. Československý vědecký ústav vojenský.

- ↑ Rudoplh, Richard L. (2008). Banking and Industrialization in Austria-Hungary: The Role of Banks in the Industrialization of the Czech Crownlands, 1873-1914. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1975), A History of the Crusades: The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Univ of Wisconsin Press, p. 604

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "howitzer". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ The Concise Oxford English Dictionary (4 ed.). 1956. pp. Howitzer.

- ↑ Hermann, Paul (1960). Deutsches Wörterbuch (in German). pp. Haubitze.

- 1 2 3 4 Sedláček, Petr. "Právní úprava držení a nošení zbraní v letech 1945–1989 [Legislation on possession and carrying of firearms in 1945-1989]" (PDF) (in Czech). Masarykova Univerzita v Brně. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 28(1)(B)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 29(1)(N)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 9(2)(C) (effective after 1 July 2014)

- ↑ Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic (1999), Ruling No. 68/1999 Coll., in the matter of petition for abolishment of Section 44(1)(D) and Section (44)(2) of the Act No. 288/1995 Coll., on Firearms and Ammunition (in Czech), Brno, retrieved 18 January 2014

- 1 2 Parliament of the Czech Republic (2002), Act No. 119/2002 Coll., on Firearms and Ammunition (in Czech), Prague

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 8

- 1 2 Firearms Act, Section 16(1)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 28(3)(B), 28(4)(C)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 16(2)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 18

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 24(1)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 19

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 7(1)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 21(4)(A)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 21(4)(B)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 21(4)(C)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 21(4)(D)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 21(5)(A)

- ↑ Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic (2014), Regulation No. 115/2014 Coll., on Execution of Certain Sections of Firearms and Ammunition Act (Firearms Regulation) (in Czech), Prague, Section 5(1)(A)

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 5(1)(B)

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 5(1)(C)

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 5(3)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 21(5)(B)

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 8(1)(B),(B)

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 8(1)(C)

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 8(1)(D),(E)

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 8(2)

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 6(5)

- ↑ Firearms Regulation, Section 7(2)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 28(3)

- ↑ Eligibility Regulation, Section 2(2)

- ↑ Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (2002), Regulation No. 493/2002 Coll., on Assessment of eligibility to be issued or to have a firearms license (Eligibility Regulation) (in Czech), Prague

- ↑ Eligibility Regulation, Annex No. 1

- ↑ Eligibility Regulation, Section 6(2)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 22

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 22(4)

- 1 2 Firearms Act, Section 57(1)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 23

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 18(3)

- 1 2 Firearms Act, Section 24(2)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 17(5)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 12(4)

- ↑ "ZBrojní průkaz pro cizince [Gun license for foreigners]" (in Czech). Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Government of the Czech Republic (2011), Regulation no. 315/2011, on Firearms competence exam (in Czech), Prague

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kyša, Leoš (January 28, 2011). "Počet legálně držených zbraní v Česku stoupá. Už jich je přes 700 tisíc [The number of legally owned firearms in the Czech Republic is increasing, there are already over 700 thousand of themr]" (in Czech). ihned.cz. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ↑ "Silnici na Kroměřížsku zablokoval havarovaný tank [A crashed tank blocked a road in Kroměříž district]". idnes.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ↑ "Kupte si tank, nebude! [Buy yourself a tank before they're all sold out!]". profit.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- 1 2 Firearms Act, Section 4

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 5

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 6

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 7

- ↑ Firearms Act, Sections 9-14

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 15

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 42(1)

- 1 2 Firearms Act, Section 28

- 1 2 Firearms Act, Section 9(2)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 12(5)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 12(6),(7)

- 1 2 3 Firearms Act, Section 58(2)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 14

- ↑ Criminal Code, Section 279

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 28(5)

- ↑ Czechnology. "Mapa střelnic". zbranekvalitne.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 59(4)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 76(1)(F)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 76a, 57

- ↑ "Myslivci se na poslední hon v roce posilnili čajem s citrónem [Hunters drank tea with lemon during the year's last hunt.]". Česká televize. 19 December 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ "Praha je bezpečnější než Vídeň [Prague is safer than Vienna]". Česká televize. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic. "Information on the number of firearms and holders of firearms licenses and armament licenses in the Czech Republic and on the misdemeanors and criminal acts in this area" (in Czech). 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 28(1)

- 1 2 Firearms Act, Section 28(2)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 28(3),(4)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 28(3)(A)

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 28(3)(B) alinea 2

- 1 2 Parliament of the Czech Republic (1990), Act No. 273/2008 Coll., on the Police of the Czech Republic (in Czech), Prague, Section 110

- ↑ Firearms Act, Section 61

- ↑ Fialová, Markéta (13 May 2013). "PLZEŇSKO - Při květnových oslavách nebyl zjištěn trestný čin, ani přestupek [No crimes nor misdemeanors found during May celebrations]" (in Czech). Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- 1 2 Firearms Act, Section 4(B)(2)

- ↑ Parliament of the Czech Republic (2009), Act No. 40/2009 Coll., the Criminal Code (in Czech), Prague, Section 29

- ↑ Parliament of the Czech Republic (2012), Act No. 89/2012 Coll., the Civil Code (in Czech), Prague, Section 14

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Novotný, Oto (2004). Trestní právo hmotné. Praha: ASPI.

- ↑ "CZ 2075 RAMI Subcompact" (in Czech). Česká zbrojovka. January 28, 2011. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- 1 2 Třeček, Čeněk. "VV si našly cestu do Sněmovny, prosazují větší právo na obranu [The Public Affairs party presses for greater right of self-defense]". iDnes.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Decision published as No 804/2011 in the magazine Soudní judikatura (Judicial Decisions) (in Czech)

- ↑ Supreme Court of the Czech Republic (24 October 2001), Decision No. 5 Tz 189/2001 (in Czech), Brno

- ↑ Supreme Court of the Czech Republic (19 December 1994), Decision No. 7 To 202/94 (in Czech), Brno

- ↑ Supreme Court of the Czech Republic, Decision No. 41/1980 Coll. (in Czech), Brno

- 1 2 3 Supreme Court of the Czech Republic (18 December 2013), Decision No. 3 Tdo 1197/2013 (in Czech), Brno

- ↑ Supreme Court of the Czech Republic (17 February 1981), Decision No. 3 To 2/1981 (in Czech), Brno

- ↑ "Barman z Hořovic zastřelil hosta v sebeobraně, konstatovala policie [Bartender in Hořovice shot a guest in self defense, police held]" (in Czech). idnes.cz. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Muž v pražských Čimicích načapal zloděje v garáži, jednoho postřelil [Man in Čimice caught burglars, shot one of them]" (in Czech). idnes.cz. 10 March 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Rosenauer, Jan (15 December 2008). "S agresorem z očí do očí; na čí straně je zákon? [Eye to eye with an aggressor: whom does the law protect?]" (in Czech). Český rozhlas. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Milost prezidenta předem odmítám [I refuse a presidential pardon in advance]" (in Czech). nnoviny. 1995. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Vojíř, Aleš (10 October 2004). "Prezident dal milost muži, který zastřelil zloděje aut [President pardoned a man who shot a car thief]" (in Czech). ihned.cz. Retrieved 13 October 2004.

- ↑ "Studentka se rybičkou bránila, řekla policie [The police held that the student was defending herself.]" (in Czech). idnes.cz. 8 October 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Střílel na útočníka, soud mu dal svobodu [He shot an attacker, a court exonerated him]" (in Czech). aktualne.cz. 19 September 2006. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Klaus omilostnil majitele sběrny, který postřelil z brokovnice zloděje [Klaus pardoned an owner of scrap-yard who shot a thief]" (in Czech). ihned.cz. 30 March 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Student, who killed a foreigner in Prague, acted in self-defense]" (in Czech). ihned.cz. 21 January 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Muž zastřelil romského mladíka v Tanvaldu v sebeobraně, rozhodl žalobce [Man shot the Roma youngster in Tanvald in self-defense according to State Attorney]" (in Czech). novinky.cz. 18 June 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Přibylo žadatelů o zbrojní průkaz [The number of firearm license applications is rising]" (in Czech). Police of the Czech Republic. 2016-01-09. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "Více zbraní nezpůsobí více vražd, bojíme se jich kvůli televizi [More guns don't cause more murders, we fear them because of television]". Mladá fronta DNES (in Czech). 27 February 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ↑ Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic. "Report on situation in the area of public order and internal security in the Czech Republic" (in Czech). 2005: 32. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic. "Report on situation in the area of public order and internal security in the Czech Republic" (in Czech). 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Vojtěch, Kučerák (13 August 2012). "Zbraně k zločinům? Ve většině případů jsou nelegální [Criminals' firearms? In most cases, they are illegal]" (in Czech). denik.cz. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ "Někdo velmi lhal, naznačil policista [Someone lied miserably, a policeman suggested]" (in Czech). idnes.cz. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Policisté dopadli lesního střelce, prý by vraždil znovu [The Police have caught the Forest Killer, allegedly he was about to murder again]" (in Czech). idnes.cz. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ↑ Třeček, Čeněk. "Lesní vrah Kalivoda spáchal za mřížemi sebevraždu [Kalivoda the Forest Killer committed suicide behind the bars]" (in Czech). idnes.cz. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- 1 2 David, Karásek. "Tisková zpráva sdružení gunlex k povinným psychotestům [Press release of gun lex on mandatory psychological tests]" (in Czech). Gun Lex. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Ďuričko zůstane ve vězení, potvrdil Nejvyšší soud [The Supreme Court decided that Ďuričko will remain behind bars]" (in Czech). e15.cz. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Šrubař, Martin. "Vrah dědečka a jeho vnučky je učitel. Dívka s ním údajně čekala dítě [The murderer of the grandfather and granddaughter is her teacher, she was supposedly pregnant with him]" (in Czech). denik.cz. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Šrubař, Martin. "Učitel střílel jako šílený, použil všechny tři pistole, které měl s sebou [The teacher was shooting like crazy, he used all three firearms he had with him]" (in Czech). denik.cz. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Gabzdyl, Josef. "Odvolací soud zpřísnil dvojnásobnému vrahovi z Raškovic trest na 27 let [The appellate court delivered a stricter sentence of 27 years imprisonment to the Raškovice murderer]" (in Czech). idnes.cz. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ↑ "8 dead, plus gunman, in Czech restaurant shooting rampage". Fox News Channel. February 24, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Kriminalita po Listopadu v Česku výrazně vzrostla [The Criminality Rate has risen after the Velvet Revolution]" (in Czech). novinky.cz. October 11, 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ↑ "Norský vrah sháněl zbraně i u motorkářů v Praze" (in Czech). Týden. 24 July 2011. (Google Translate link)

- ↑ "Zbraně jel Breivik nakoupit do "nebezpečné Prahy"" (in Czech). novinky.cz. 24 July 2011. (Google Translate link)

- ↑ "Oslo killer sought weapons from Prague's underworld". Czech Position. 25 July 2011.

- ↑ "Chemik zafascynowany Breivikiem [A chemist fascinated by Breivik]". Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). 21 November 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ "Policie nepomáhá a nechrání, soudí lidé na Šluknovsku a ozbrojují se [The people in Šluknov District believe that the Police do not help and do not protect them, they are arming themselves]" (in Czech). iDnes.cz. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ↑ "Novely zbrojního zákona, související nařízení a vyhlášky na stránkách sdružení" (in Czech). GunLEX. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

- ↑ "Má váš poslanec zbrojní průkaz a zbraň? Podívejte se [Is your Deputy armed? Check it out]" (in Czech). lidovky.cz. June 10, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Firearms and the internal security of the EU: protecting citizens and disrupting illegal trafficking" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ↑ "Volby do Evropského parlamentu 2014 [2014 Elections to the European parliament]" (in Czech). gunlex.cz. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ↑ "European Commission strengthens control of firearms across the EU". European Commission. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ↑ "Le B7? Mai usate!". armietiro.it. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ↑ "USNESENÍ VLÁDY ČESKÉ REPUBLIKY ze dne 11.května 2016 č. 428 k Analýze možných dopadů revize směrnice 91/477/EHS o kontrole nabývání a držení střelných zbraní". Czech Government. Retrieved 2016-12-04. "Vláda (...) II. ukládá předsedovi vlády, 1. místopředsedovi vlády pro ekonomiku a ministru financí, ministrům vnitra, obrany, průmyslu a obchodu, zahraničních věcí, zemědělství a ministryni práce a sociálních věcí 1. podniknout veškeré procesní, politické a diplomatické kroky k zabránění přijetí takového návrhu směrnice, kterou se mění směrnice 91/477/EHS, který by nepřiměřeně zasahoval do práv občanů České republiky a měl negativní dopady na vnitřní pořádek, obranyschopnost, hospodářskou situaci nebo zaměstnanost v České republice, 2. zasadit se o prosazení takových změn návrhu směrnice, kterou se mění směrnice 91/477/EHS, které umožní zachování současné úrovně práv občanů České republiky a umožní předejít negativním dopadům na vnitřní pořádek, obranyschopnost, hospodářskou situaci nebo zaměstnanost v České republice."

- ↑ "usnesení Poslanecké sněmovny". Czech Parliament. Retrieved 2016-12-04. "Poslanecká sněmovna 1. v y j a d ř u j e n e s o u h l a s se záměrem Evropské komise omezit možnost nabývání a držení zbraní, které jsou drženy a užívány legálně v souladu s vnitrostátním právem členských zemí Evropské unie; 2. o d m í t á , aby Evropská komise zasahovala do funkčního systému kontroly, evidence, nabývání a držení zbraní a střeliva nastaveného právním řádem České republiky; 3. v y j a d ř u j e p o d p o r u vytvoření všech funkčních opatření, které povedou k potírání nelegálního obchodu, nabývání, držení a jiné nelegální manipulace se zbraněmi, střelivem a výbušninami; 4. o d m í t á , aby Evropská komise v reakci na tragické události spojené s teroristickými činy v Paříži perzekvovala členské státy a jejich občany neodůvodněným zpřísněním legálního držení zbraní; 5. d o p o r u č u j e p ř e d s e d o v i v l á d y Č e s k é r e p u b l i k y , aby podnikl všechny právní a diplomatické kroky k zabránění přijetí takové směrnice, která by narušovala český právní řád v oblasti obchodu, kontroly, nabývání a držení zbraní a tím nevhodně zasahovala do práv občanů České republiky."

- ↑ "401.USNESENÍ SENÁTU z 22. schůze, konané dne 20. dubna 2016". Czech Senate. Retrieved 2016-12-04. " 2. upozorňuje však, že v návrhu směrnice se Komise měla zaměřit primárně na nelegální nabývání a držení střelných zbraní, jejich řádné znehodnocování a na nedovolený obchod s nimi, neboť k teroristickým útokům jsou využívány právě nelegální zbraně, nikoli zbraně držené v souladu s právními předpisy členských států; 3. nesouhlasí proto s opatřeními obsaženými v návrhu směrnice, která by vedla k omezení legálních držitelů střelných zbraní a narušení vnitřní bezpečnosti České republiky, aniž by to mělo zjevný preventivní či represivní účinek na osoby držící zbraně nelegálně; taková opatření by byla v rozporu se zásadami subsidiarity a proporcionality"

- ↑ "Joint Declaration of Ministers of the Interior Meeting of Interior Ministers of the Visegrad Group and Slovenia, Serbia and Macedonia". Visegrad Group. Retrieved 2016-12-04. line feed character in

|title=at position 47 (help) - ↑ "Analýza možných dopadů revize směrnice 91/477/EHS o kontrole nabývání a držení střelných zbraní". Czech Ministry of Interior. Retrieved 2016-12-04. line feed character in

|title=at position 79 (help) - 1 2 Koníček, Tomáš Tomáš; Kocábek, Pavel. "Prevence přepadení [Preventing Assault]" (in Czech). Ministerstvo vnitra. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ↑ Parliament of the Czech Republic (1990), Act No. 84/1990 Coll., on the Right of Assembly (in Czech), Prague, Section 7(3)