Goodwin Sands

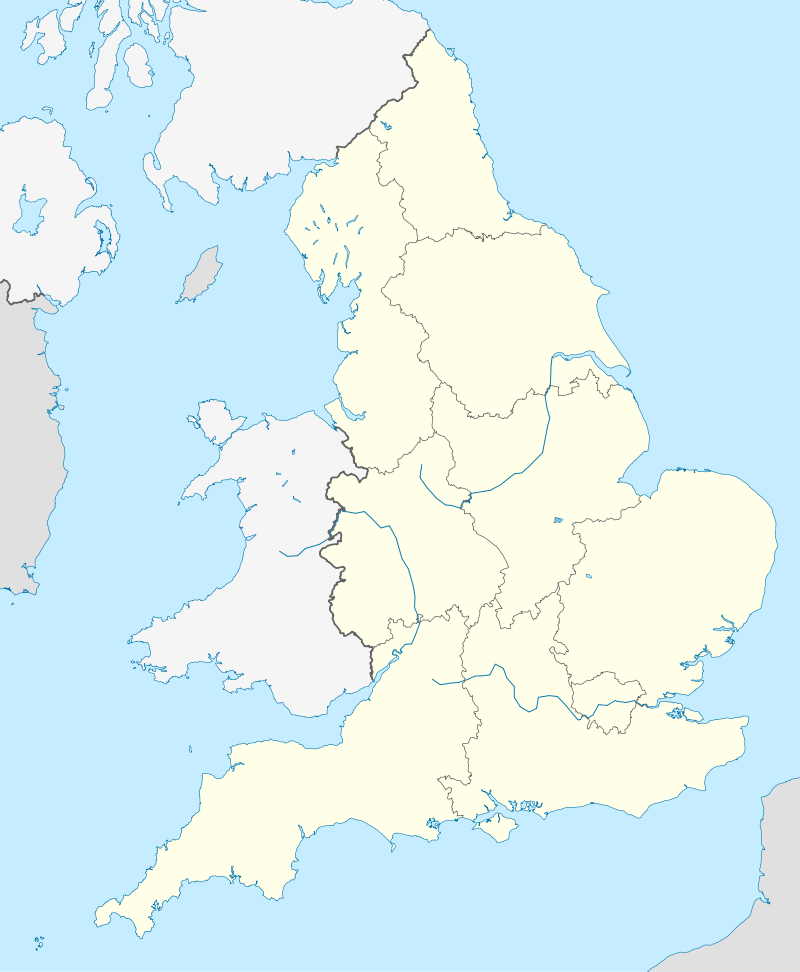

Coordinates: 51°16′25″N 1°30′30″E / 51.27361°N 1.50833°E

The Goodwin Sands is a 10-mile (16 km) long sandbank in the English Channel lying 6 miles (10 km) off the Deal coast in Kent, England.[1] The area consists of approximately 25 m (82 ft) of fine sand resting on an Upper Chalk platform belonging to the same geological feature that incorporates the White Cliffs of Dover. The banks lie between 8 m (26 ft) and 15 m (49 ft) beneath the surface, depending on location, since tides and currents are constantly shifting the shoals.

More than 2,000 ships are believed to have been wrecked upon the Goodwin Sands because they lie close to the major shipping lanes through the Straits of Dover. Due to the dangers, the area – which also includes Brake Bank[2][3] – is marked by numerous lightvessels and buoys.

Notable shipwrecks include the HMS Stirling Castle in 1703, VOC ship Rooswijk in 1740, the SS Montrose in 1914, and the South Goodwin Lightship, which broke free from its anchor moorings during a storm in 1954.[4] Several naval battles have been fought nearby, including the Battle of Goodwin Sands in 1652 and the Battle of Dover Strait in 1917.

When hovercraft ran from Pegwell Bay, Ramsgate they used to make occasional trips over the sands, where boats could not safely go.

Southeast from Goodwin Sands lies the Sandettie Bank.

Navigational aids

There is currently a lightship on the end of the sands, on the farthest part out, to warn ships. The sands were once covered by two lighthouses on the Kent mainland, one each covering the north and south ends of the sands. The South Foreland lighthouse is now owned by the National Trust, and the North Foreland lighthouse is still in operation.

The Island of Lomea

In 1817, borings in connection with a plan by Trinity Board to erect a lighthouse on the Sands revealed, beneath fifteen feet of sand, a stratum identified by Charles Lyell as London clay lying upon a chalk basement. Based on this, Lyell proposed that the Sands were the eroded remains of a clay island similar to Sheppey, rather than a mere shifting of the sea bottom shaped by currents and tides.[5][6]

Lyell's assessment was uncritically followed until the mid-20th century, and enlarged upon by G.B. Gattie[7] who asserted, based on unsourced legends, that the sands were once the fertile low-lying island of Lomea, which he equated with an island said to be known to the Romans as Infera Insula ("Low Island").[8] This, Gattie said, was owned in the first half of the 11th century by Godwin, Earl of Wessex, after whom the sands are named.[9] When he fell from favour, the land was supposedly given to St. Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury, whose abbot failed to maintain the sea walls, leading to the island's destruction, some say, in the storm of 1099 mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. However, the island is not mentioned in the Domesday Book, suggesting that if it existed it may have been inundated before that work was compiled in 1085–86.[10] The earliest written record of the name "Lomea" seems to be in the De Rebus Albionicis (published 1590) by John Twyne, but no authority for the island's existence is given.[11] There is a brief mention of a sea-tide inundation in 1092 creating the Godwin sands in a 19th-century book of agricultural records, reissued in 1969.[12]

The modern geological view is that the island of Lomea probably never existed.[13] Although the area now covered by sands and sea was once dry land, the Strait of Dover opened in the Weald-Artois chalk range in prehistory – between around 7600 BC and 5000 BC[14] – not within historical time.

Notable events

17th century

- John, the son of Phineas Pett of Chatham, was involved in an ordeal in the beginning of October 1624, when occurred: "a wonderful great storm, through which many ships perished, especially in the Downs, amongst which was riding there the Antelope of His Majesty, being bound for Ireland under the command of Sir Thomas Button, my son John then being a passenger in her. A merchant ship, being put from her anchors, came foul of her, and put her also from all her anchors, by means whereof she drove upon the brakes [the Sands], where she beat off her rudder and much of the run abaft, miraculously escaping utter loss of all, for that the merchant ship that came foul of her, called the Dolphin, hard by her utterly perished, both ship and all the company. Yet it pleased God to save her, and got off into the downs, having cut all her masts by the board, and with much labour was kept from foundering."[15] Phineas Pett received news of the shipwreck at Deal, and was dispatched by the Lord Admiral to attend to the ship and use his best means to save her. He used chain pumps, replaced the rudder, and fitted jury masts, by which effort she was safely brought to Deptford Dock.

- In 1690 HMS Vanguard, a 90-gun second-rate ship of the line, struck the Sands, but was fortunate enough to be got off by the boatmen of Deal.

Great Storm of 1703

In the Great Storm of 1703 at least 13 men-of-war and 40 merchant vessels were wrecked in the Downs, with the loss of 2,168 lives and 708 guns. Yet, to their credit, the Deal boatmen were able to rescue 200 men from this ordeal.

Naval vessels lost to the sands included:

- HMS Northumberland, Deptford built, and from there locally manned, lost with all hands

- HMS Restoration, Deptford built, and from there locally manned, lost with all hands

- HMS Stirling Castle,[16] a 70-gun third-rate built at Deptford in 1679

- The Woolwich fourth-rate HMS Mary, totally overwhelmed with the loss of 343 men

- The boom ship HMS Mortar, lost with all 65 of her crew.

18th and 19th centuries

According to legend the Lady Lovibond was wrecked on the Goodwin Sands on 13 February 1748, amidst alleged controversy over the cause of her sinking in which all hands were lost. She is said to reappear every fifty years as a ghost ship.[17] No references to the shipwreck are known to exist in contemporary records or sources, including newspapers, Lloyd's List or Lloyd's Register.

The Admiral Gardner was wrecked in January 1809, with its cargo, a large number of East India Company X and XX copper cash coins, belonging to Matthew Boulton.[18] The wreck was found in 1984 and some coins were salvaged in 1985 during a licensed dive.

The brig Mary White was wrecked on the Sands in a storm in 1851; seven men of her crew were rescued by the lifeboat from Broadstairs.

The mail paddle steamer SS The Violet was driven onto the sands during a storm on 5 January 1857 with the loss of seventeen crew, a mail guard, and one passenger.

20th century

The Belgian cargo ship SS Cap Lopez was wrecked on the sands in 1907.

HMT Etoile Polaire, a naval trawler, was sunk by a mine on the sands, on 15 December 1915, at the height of World War One.

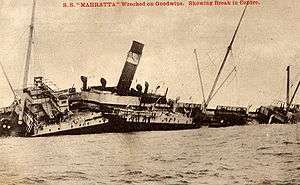

Two ships named SS Mahratta ran aground on the Sands, one in 1909 and the other in 1939.

The passenger ship SS Chusan collided with the freighter Prospector near the Sands in June 1953, severely damaging and nearly sinking her.

The Radio Caroline vessel MV Ross Revenge drifted onto the Sands in November 1991, effectively ending the era of offshore pirate radio in Britain.

21st century

On 10 June 2013, a Dornier Do 17 Z2 was raised from Goodwin Sands. The German bomber had made an emergency landing in the sea over the Sands on 26 August 1940 after a bombing raid. Two of the four-man crew were killed on impact, the remaining crew becoming POWs.[19] The Dornier was located on the Sands in September 2008 and plans were made to recover it, as it is one of two surviving aircraft of this type.[20]

The salvage started on 3 May 2013 with the plane destined eventually for RAF Hendon in 2015,[21] though poor weather and the position of the plane on chalk rather than the silt expected caused the plan to be amended to attaching ropes to three points on the fuselage.[22] The plane was finally lifted on 10 June 2013.[23] It is believed to be from 7 Staffel, III Gruppe/KG3 (7th Sqn of 3rd Group of Bomber Wing 3) operating from Sint-Truiden aerodrome 60 km east of Brussels, shot down on 26 Aug 1940 by a Boulton Paul Defiant of No. 264 Squadron RAF, based in Hornchurch, either one crewed by Desmond Hughes and Fred Dash[24] or one of the three 264 Squadron aircraft shot down soon after in a battle with Bf 109E fighter escorts of the German fighter wing JG 3.[25][26]

Potential airport site

The August 1969 issue of Dock and Harbour Authority magazine carried an article 'A National Roadstead' which reported on a 1968 proposal to the Ministry of Transport for construction of a deep water port on the reclaimed Goodwin Sands. In 1985 consultants Sir Bruce White Wolfe Barry and Partners promoted a proposal for developing an International Freeport combined with a two-runway airport located on three reclaimed islands on the sands.[27] In 2003, the idea was still under consideration.[28] Being far from residential areas it has the advantage of 24-hour-a-day take-offs and landings without causing disturbance.

In December 2012, the site of the Goodwin Sands was once again promoted as a potential location for a £39 billion 24-hour airport to become the UK's hub airport.[29] Engineering firm Beckett Rankine believes their proposals for up to five offshore runways at Goodwin Airport are the 'most sustainable solution' with the 'least adverse impact' when compared to other options that have been proposed for the expansion of runway capacity in the Southeast. They claim that this is due to the absence of statutory environmental protection on the Goodwin Sands and the alignment of the runways which avoids any overflying of the coast.[30]

Cricket

In the summer of 1824, Captain K. Martin, then the Harbourmaster at Ramsgate, instituted the proceedings of the first known cricket match on the Goodwin Sands, at low water. Such was the tenacity of local mariners that a tradition sprang up that survives to this day, whereby those so inclined make the journey to the Sands for a leisurely few hours in pursuit of this very English pastime. . An annual cricket match was until 2003 played on the sands at low tide, and a crew filming a reconstruction of this for the BBC television series Coast had to be rescued by the Ramsgate lifeboat when they got into difficulty in 2006.[31]

When the Royal Marines School of Music existed at Deal, it played a game of cricket on a suitable day each summer.

Literary references

William Shakespeare mentions The Sands in The Merchant of Venice, Act 3 Scene 1:

- Why, yet it lives there uncheck'd that Antonio hath a ship of rich lading wrecked on the narrow seas; the Goodwins, I think they call the place; a very dangerous flat and fatal, where the carcasses of many a tall ship lie buried, as they say, if my gossip Report be an honest woman of her word.

William Shakespeare mentions Goodwin Sands in King John, Act 5 Scene 5:

- Messenger:The Count Melun is slain; the English Lords\ By his persuasion are again fall'n off,\ And your supply, which you have wish'd so long,\ Are cast away and sunk on Goodwin Sands. [32]

Mary Wroth refers to Goodwin Sands as a place of shipwreck in her sonnet sequence Pamphilia to Amphilanthus (1621):

- Like to a Ship on Goodwins cast by winde, / The more shee strive, more deepe in Sand is prest... (Sonnet 6, 5-6).

Herman Melville mentions them in Moby-Dick, Chapter VII, The Chapel:

- In what census of living creatures, the dead of mankind are included; why it is that a universal proverb says of them, that they tell no tales, though containing more secrets than the Goodwin Sands...

R. M. Ballantyne, the Scottish writer of adventure stories, published The Floating Light of the Goodwin Sands in 1870.

W. H. Auden quotes the phrase "to set up shop on Goodwin Sands" in his poem In Sickness and in Health. This is a proverbial expression meaning to be shipwrecked.[33]

G. K. Chesterton's poem The Rolling English Road refers to "the night we went to Glastonbury by way of Goodwin Sands."

Charles Spurgeon mentions them in The Soul Winner, chapter 15 "Encouragement to Soul-Winners."

- Their theology shifts like the Goodwin Sands, and they regard all firmness as so much bigotry.

Ian Fleming refers to the Goodwin Sands in Moonraker, one of the James Bond novels, as well as making them a major plot point in his children's story Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

The sands are depicted in the 1929 film The Lady from the Sea, which is sometimes known by the title of Goodwin Sands.

In the 2014 biographical film Mr. Turner, the first husband of the housekeeper Mrs. Booth is mentioned as having died in a boating accident at Goodwin Sands.

"Old Goodman's Farm", appearing in the Rudyard Kipling poem Brookland Road refers to the Goodwin Sands and the legend of their origin as an island belonging to Earl Godwin.

In the novel The Shivering Sands by Victoria Holt the Goodwin sands play a major plot point and the masts from wrecked ships are often sighted from the shore.

In Patrick O'Brian's Post Captain, Stephen Maturin explores the sands and must dive for his boots as the tide floods.

In the short story "Flood on the Goodwins" (1933) by Arthur Durham Divine, on a foggy night during World War One, a German saboteur orders a British mariner at gunpoint to take him to the coast of Belgium. Instead, the mariner circles for hours and then, telling the saboteur they have reached Belgium, strands the German at low tide on the Goodwins, six miles from shore, knowing that the tide will drown the villain.

In Julian Stockwin's Invasion the Sands are both a hindrance and protection for the British fleet assembled for the rapid deployment against Napoleon's invasion armada. The protagonist Kydd even takes part in the rescue of a merchantman vessel being gale forced onto the Sands.

See also

References

- ↑ Cloet, R. L. (1954). "Hydrographic Analysis of the Goodwin Sands and the Brake Bank". The Geographical Journal. 120 (2): 203–215. doi:10.2307/1791536. JSTOR 1791536.

- ↑ R. L. Cloet, "Hydrographic Analysis of the Goodwin Sands and the Brake Bank", The Geographical Journal, 120.2 (June 1954:203–215). Cloet demolished the story that the Goodwin Sands had been a low-lying island, identifying its hydrofoil shape formed by currents, and charting its anti-clockwise drift.

- ↑ Cloet, R. L. (1961). "Development of the Brake Bank". The Geographical Journal. 127 (3): 335–339. doi:10.2307/1794954. JSTOR 1794954.

- ↑ "Crew of the South Goodwin light vessel". www.portcities.org.uk. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ Principles of geology Vol. 1, pp. 408–409, Charles Lyell

- ↑ Lyell, Principles of Geology, (London, I830), vol. I, ch. xx "Encroachments of the Sea" p 276.

- ↑ Gattie, Memorials of the Goodwin Sands (London, 1904) noted by Cloet 1954:204 and note 1

- ↑ "Gattie, quoting some 'early writers', suggests that the Goodwins are the 'Infera Insula' they mention". (Cloet 1954).

- ↑ Another theory is that the sands' name came from Anglo-Saxon gōd wine = "good friend", an ironic name given by sailors.

- ↑ Edwin Guest, Origines Celticae (a Fragment) and Other Contributions to the History of Britain 1883:530.

- ↑ Charles G. Harper, The Kentish Coast 1914:231.

- ↑ Stratton, J.M. (1969). Agricultural Records. John Baker. p. 17. ISBN 0-212-97022-4.

- ↑ Unsolved Mysteries of the Sea, p. 27, Lionel and Patricia Fanthorpe, 2004

- ↑ Climate, history and the modern world, p. 116, H. H. Lamb, 1996

- ↑ From the Autobiography of Phineas Pett.

- ↑ Smith, B. S. (2010). "A Cross-Staff from the Wreck of HMSStirling Castle(1703), Goodwin Sands, UK, and the Link with the Last Voyage of Sir Cloudesley Shovell in 1707". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 39: 172. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2009.00245.x.

- ↑ Randall Floyd, E (2002) In the Realm of Ghosts and Hauntings, Harbor House, Augusta, Georgia, 'Lady Lovibond: Ghost schooner still sails the English coast', P103-05

- ↑ "The loss of the Admiral Gardner". Shoho mint. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ "Luftwaffe Dornier 17 at Goodwin Sands 'still intact'". BBC News. 8 April 2011.

- ↑ http://www.key.aero/view_news.asp?ID=2477&thisSection=historic

- ↑ Nick Higham (3 May 2013). "Dornier 17: Salvaging a rare WWII plane from the seabed". BBC news. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ↑ Nick Higham (31 May 2013). "German Dornier 17 salvage hit by English Channel weather". BBC news. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ "WWII Dornier bomber raised from English Channel". BBC news. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ Jasper Copping and Jeevan Vasagar (19 June 2013). "The doomed flight of the last Dornier". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ "Dornier Do 17Z Werke nr. 1160". Royal Air Force Museum, 6 December 2012. Retrieved: 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "Dornier 17 Conservation: Identification". Royal Air Force Museum, 6 December 2012. Retrieved: 5 May 2013.

- ↑ http://beckettrankine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/the_downs_a_common_marketplace_low_res.pdf

- ↑ Gadher, Dipesh (2 March 2008). "How to escape Heathrow hell". The Times. London.

- ↑ "Fourth South East England hub airport proposal unveiled". BBC News. 19 December 2012.

- ↑ goodwinairport.com

- ↑ "Now that's a real wash-out". Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ King John, Act. 5, sc. 5, line 10-13

- ↑ C. Merton Babcock, The Language of Melville's "Isolatoes", Western Folklore, Vol. 10, No. 4. (Oct., 1951), pp. 285–289 ; W. Carew Hazlitt, English Proverbs and Proverbial Phrases, London, 1869, p. 430.

Further reading

- Richard Larn and Bridget Larn – Shipwrecks of the Goodwin Sands (Meresborough Books, 1995) ISBN 0-948193-84-0

- Steve Conway – Shiprocked – Life On The Waves With Radio Caroline (Liberties Press, Dublin, 2009) ISBN 978-1-905483-62-4 (author gives his account of running aground on the Goodwin Sands and helicopter rescue)

- Raymond Lamont Brown – 'Phantoms of the Sea' (Taplinger Publishing Company, NY 1972) ISBN 0-8008-5556-6

- Lyon, D. J. (1980). "The Goodwins wreck". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 9 (4): 339. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.1980.tb01152.x.

External links

- goodwin-sands 2009 survey from United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (at Yumpu.com) PDF-File, 52 pages

- An historical sketch, including a map of the sands and their environs

- Historic Deal information on the Goodwin Sands