Glanum

|

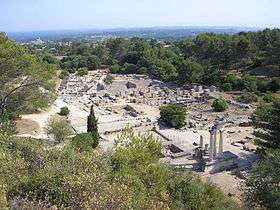

Excavations of ancient Glanum, at the foot of Mont Gaussier. The church spire of modern Saint-Rémy-de-Provence can be seen in the middle distance to the left. | |

Shown within France | |

| Alternate name | Γλανόν |

|---|---|

| Location | Near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France |

| Coordinates | 43°46′26″N 4°49′57″E / 43.77389°N 4.83250°ECoordinates: 43°46′26″N 4°49′57″E / 43.77389°N 4.83250°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Salyens |

| Founded | 6th century BCE |

| Abandoned | 260 AD |

| Periods | Celto-Ligurian, Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1921, 1982 |

| Archaeologists | Jules Foremigé, Pierre LeBrun, Henri Roland |

| Condition | In ruins |

Glanum (Hellenistic Γλανόν,[1] as well as Glano,[2] Calum,[3] Clano,[4] Clanum, Glanu, Glano) was an oppidum, or fortified town in present day Provence, founded by a Celto-Ligurian people called the Salyes in the 6th century BCE.[5] It became officially a Roman city in 27 BCE and was abandoned in 260 AD. It is located on the flanks of the Alpilles, a range of mountains in the Bouches-du-Rhône département, about 20 km (12 mi) south of the modern city of Avignon, and a kilometre south of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. It is particularly known for two well-preserved Roman monuments of the 1st century B.C., known as les Antiques, a mausoleum and a triumphal arch (the oldest in France).

History

The Celto-Ligurian oppidum

Between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC, the Salyens, the largest of the Celto-Ligurian tribes in Provence, built a rampart of stones on the peaks that surrounded the valley of Notre_Dame-de-Laval, and constructed an oppidum, or fortified town, around the spring in the valley, which was known for its healing powers. A shrine was built at the spring to Glanis, a Celtic god. The town grew, and a second wall was built in the 2nd century BC.[6]

The town had a strong Celtic identity, shown by the names of the residents (Vrittakos, Eporix, Litumaros); by the names of the local gods (Glanis and his companions, the Glanicae, (similar to the Roman Matres); and the goddesses Rosmerta and Epona); by the statues and pottery; by the customs, such as displaying the severed heads of enemies at the city gate; and by the cooking utensils found in the ruins, which showed that the people of Glanis boiled their food in pots, rather than frying it in pans like other Mediterranean tribes.[7]

The people of Glanum were in early contact with the Greek colony of Massalia, present day Marseille, which had been founded in about 600 BC. The contact influenced the architecture and art of Glanum- villas were built in the Hellenic style. But by the 2nd century BC conflicts and wars arose between the Salyens and the Greeks of Marseille, who not having a powerful army, called upon the assistance of their Roman allies. In 125 BC the Salyens were defeated by the army of the Roman consul Marcus Fulvius Flaccus, and the following year decisively defeated by C. Sextus Calvinus. Many of the old monuments of Glanum were destroyed.

Due to its commercially useful location on the Via Domitia, and the attraction of its healing spring, the town prospered again. The city produced its own silver coins and built new monuments. The prosperity lasted until 90 BC when the Salyens again rebelled against Rome. The public buildings of Glanum were again destroyed. The rebellion was crushed this time by the Consul Caecilius, and the remains of the main buildings demolished and replaced by more modest structures.[8]

The Roman town

In 49 BC Julius Caesar captured Marseille, and after a period of destructive civil wars, the Romanization of Provence and Glanum began.

In 27 BC the Emperor Augustus created the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis, and in this province Glanum was given the title of Oppidum Latinum, which gave residents the civil and political status of citizens of Rome. A triumphal arch was built outside the town between 10 and 25 BC, near the end of the reign of Augustus, (the first such arch to be built in Gaul), as well as an impressive mausoleum of the Julii family, both still standing.

In the 1st century BC, under the Romans, the city built a new forum, temples, and a curved stone arch dam, Glanum Dam, the oldest known dam of its kind,[9][10] and an aqueduct, which supplied water for the towns fountains and public baths.

Glanum was not as prosperous as the Roman colonies of Arles, Avignon and Cavaillon, but by the 2nd century AD it was wealthy enough to build impressive shrines to the Emperors, to enlarge the forum, and to have extensive baths and other public buildings clad in marble.

Destruction, rediscovery and excavation

Glanum did not survive the collapse of the Roman Empire. The town was overrun and destroyed by the Alamanni in 260 AD and subsequently abandoned, its inhabitants moving a short distance north into the plain to found a city that eventually became modern day Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

After its abandonment Glanum became a source of stone and other building materials for Saint-Remy. Since the Roman system of drains and sewers was not maintained, the ruins became flooded and covered with mud and sediment. The mausoleum and triumphal arch, together known as "Les Antiques," were famous, and were visited by King Charles IX, who had the surroundings cleaned up and maintained. Some excavations were made around the monuments as early as the 16th and 17th centuries, finding sculptures and coins, and by the Marquis de Lagoy in the Vallons-de-Notre-Dame in the 19th century.

The first systematic excavations began in 1921, directed by the architect of historic monuments, Jules Foremigé. From 1921 until 1941, the archeologist Pierre LeBrun worked on the site, discovering the baths, the basilica, and the residences of the northern part of the town. From 1928 to 1933, Henri Roland (1887–1970) worked on the Iron Age sanctuary, to the south. From 1942 until 1969, Roland took over the work and excavated the area from the forum to the sanctuary. The objects he discovered are on display today at the Hotel de Sade in nearby Saint-Remy. New excavation and exploration work began in 1982, devoted mainly to the preservation of the site, and to exploring beneath sites already discovered for older works.[11]

Monuments of Glanum

Mausoleum of the Julii

The Mausoleum of the Julii, located across the Via Domitia, to the north of, and just outside the city entrance, dates to about 40 BCE, and is one of the best preserved mausoleums of the Roman era.[12]

A dedication is carved on the architrave of the building facing the old Roman road, which reads:

SEX · M · L · IVLIEI · C · F · PARENTIBVS · SVEIS

Sextius, Marcus and Lucius Julius, sons of Gaius, to their forebears

It is believed that the mausoleum was the tomb of the mother and father of the three Julii brothers, and that the father, for military or civil service, received Roman citizenship and the privilege of bearing the name of the Julii, one of the most distinguished families in Rome.[12]

The mausoleum is built in three stages. The upper stage, or tholos, is a circular chapel with Corinthian columns. It contains two statues wearing togas, presumably the father and grandfather of the Julii. (The heads of the statues were lost at an earlier date, and replaced in the 18th century). The conical roof is decorated with carved fish scales, traditional for Roman mausoleums. The frieze beneath the conical roof is decorated with a rinceau featuring carvings of acanthus leaves, used in Roman mortuary architecture to represent eternal rebirth.

The middle stage, or quadrifons, is an arch with four bays. The archivoltes, or curved bands of decoration on the tops of the arches, also have acanthus leaves. At the top of each arch is the carved head of a gorgon, the traditional protector of Roman tombs.

The frieze at the top of the quadrifons is decorated with carvings of tritons, carrying the disk of the sun, and with sea monsters.

The lowest part of the mausoleum is decorated with carved garlands of vegetation, theater masks and cupids or putti, and with mythical or legendary scenes.

- North face – a battle of horsemen, and a winged victory carries a trophy.

- East face – an infantryman unhorses an Amazon warrior, a warrior takes trophies from a dead enemy, and the figure of Fame recites the story of the battle to a man and woman. The scene may be inspired by the Amazonomachy, the mythical war between the Greeks and the Amazons.

- West face – a scene from the Iliad and Trojan War, the Greeks and Trojans fighting for the body of Patroclus.

- South face – Cavaliers hunt for wild boar in a forest. One cavalier is wounded and dying in the arms of a companion. This may represent the legend of the hunt for the Calydonian Boar, conducted by Meleager, with Castor and Pollux shown on horseback.[13]

The Triumphal Arch of Glanum

The triumphal arch stood just outside the northern gate of the city, next to the mausoleum and was the visible symbol of Roman power and authority. It was built near the end of the reign of Augustus Caesar (who died in 14 AD). The upper portion of the arch, including the inscription, are missing.

The sculptures decorating the arch illustrated both the civilization of Rome and the dire fate of her enemies.

- The panel to the right of the entrance shows a female figure seated on a pile of weapons, and a Gaullish prisoner with his hands tied behind him.

- The panel to the left shows another prisoner in a Gaullish cloak, with a smaller man, wearing his cloak in the Roman style, placing his hand on the shoulder of the prisoner.

- On the reverse side of the arch are sculptures of two more pairs of Gaullish prisoners.

Glanum's monumental center

Glanum was laid out on a north-south axis through the valley of Notre-Dame-du-Vallon. At the northern end was the residential quarter, with the public baths, and at the southern end was the sacred quarter, with the spring and grotto. In the center was the monumental quarter, the site of the forum and public buildings.

The earliest monuments discovered in Glanum were built by the Salyens in the late 1st and early 2nd centuries BC and were strongly influenced by the Hellenic style of the nearby Greek colony of Marseille. They included a large building around a trapezoidal peristyle, or courtyard surrounded by columns; and a sacred well, or dromos, next to a small temple in the Tuscan style.

- The sacred well, or dromos (late 2nd century BC). The well is three meters in diameter and has a stairway with thirty-seven steps which descended to the water. There is no dedication on the temple, but it probably was connected with the sacred nature of the well. The original buildings were destroyed and the well covered over during the construction of the first Roman forum on the same site during the 1st Century BC. At the end of Antiquity the well was filled with statuary and debris from the late Roman Empire.[14] The well has been uncovered and fragments of the walls of the temple can be seen.

- The Bouleuterion (2nd -1st centuries BC) was a meeting place for notables, built in the Hellenic style, with an open space with an altar in the center surrounded by stepped rows of seats on three sides. There was a portico with three columns at one end. The northern part of the Bouleuterion was obliterated during Roman times by the construction of the Twin Temples, but the space was preserved and used as a Curia.

- The Hellenic Fountain. A small circular stone basin from the period of Greek influence, (2nd-1st centuries BC), probably a fountain, stands next to the road. This is one of the oldest fountains discovered in France.

The First Roman Forum

The first Roman forum in Glanum was built around 20 B.C., at about the time that Glanum was given the title of oppidum latinum.

- The Twin Temples. The main features of the first forum were two Corinthian temples, identical in style but one larger than the other, enclosed on three sides by a peribole, or arcade of columns. Three columns, and a part of the facade, in the style of the early years of the reign of the Emperor Augustus, have been restored/reproduced to give an idea of the building's impressive form.

- The Basilica. The first forum had on its northern side a modest basilica with two naves, used as a public hall for transacting business and legal affairs. Only the north corner of the east portico of this building still exists.

- The Monumental Fountain. A monumental fountain, dating to about 20 BC, was located on the southern end of the forum. It consisted of a rectangular basin and a semi-circular apse with Corinthian columns, which probably sheltered a statue. The fountain was supplied with water by an aqueduct from the nearby dam.

The Second Roman Forum

The second Roman forum, built between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, was the central market, business place, place of justice and site of official religious rituals. A large open space was enclosed on two sides by porticos of columns. On the southern side was a semi-circular excedre, while on the north was the basilica, the large hall that was the palace of justice and seat of government. The basilica was 47 by 24 meters in size, supported by 24 large columns. The facade has disappeared, but the back wall and side walls still exist. Behind the basilica was the curia, where a statue of the Emperor was placed in a niche in the wall. In the center was a square room which served as a tribunal and as the chapel of the cult of the Emperor.[15]

The residential quarter and the public baths

The northern part of Glanum, at the bottom of the sloping site, was the residential quarter: the site of villas and of the extensive public baths. The baths were the center of social life, and helped serve to Romanize the local population.

- The Roman Baths were built in about 75 BC. Later, during the reign of Lucius Verus (161-169 AD) they were rebuilt and the building clad with marble. Modest in size, they consisted of a pelastre, an open-air exercise area surrounded by an arcade of columns; a hall with cold baths; and two halls heated by a hypocaust, by which hot air was circulated under the rooms through brick channels. One was a hot air sweating room or laconicum, the other a caldarium, or hot bath, including a masonry bathing pool. On the south, next to the pelastre, was a large swimming pool. Water was fed into the pool through the mouth of a stone theatrical mask.[16] The original is now in the nearby museum in St. Remy but a reproduction sits in its original position.

- Hellenistic residences. The quarter contains the ruins of several villas and residences in the Greek style, pre-dating the Roman city. Between the baths and the forum was a house with a Doric peristyle, and another, called the House of Capricorn, with two surviving sections of mosaic floors, one section featuring a capricorn surrounded by four dolphins.

- The Market and the Temple of Cybele. Near the residences was a pre-Roman marketplace, surrounded by Doric columns, with four small shops on the west side. In Roman times half of the marketplace was transformed into a small temple to the Bona Dea, a goddess of the oracle, and later to Cybele. In springtime the priestesses of Cybele brought a sacred pine into the sanctuary, symbolizing the god Atys. In the temple there was also an altar dedicated to the priestess Loreia, with a stone carving of the ears of the goddess, that she might hear prayers.

- The House of the Antae was built in the style of Greek houses around the Mediterranean. A two storey house with three wings and a portico of Tuscan columns, built around a small basin of water, fed by rainwater from the roof, which channelled the water into a cistern, then into the drains which ran under the pavement of the street. It is named after two fluted antae that flank its doorway.

- The House of Atys (2nd century BC) was named for the castrated lover of Cybele, because of a marble relief of Atys found in the ruins. It had an atrium with a shallow basin, or impluvium, in the center and a well with a curbstone lip, stone benches, and was richly built. It was probably a schola, a reception hall for the college of Dendrophores, associated with the neighboring temple.[17]

The Valley of the Sacred Spring

The sacred spring of Glanum is located at the southern and highest part of the town. The valley was closed by a stone wall, built in the late 2nd or early 1st centuries BC. This wall had a gate large enough for chariots, a square tower, and a smaller gate for pedestrians. To the left and right of the gate are vestiges of the older walls, dating from between the 6th and 3rd centuries BC, making a rampart 16 meters high.

- The Doric portico. Just inside the gate was a building with a portico of doric columns. Vestiges remain of the original structure from the 2nd to 1st century BC. It was rebuilt in about 40 BC, and parts of the columns and portico from this period have been restored. Inside the building were small basins fed by water conduits in the back wall, suggesting that this building was a place where pilgrims to the spring would ritually wash and purify themselves.

- The Temple of Valetudo. This small temple was dedicated to Valetudo, the Roman goddess of health. The inscription indicates that it was built by Agrippa, the future son-in-law of the Emperor Augustus. The Corinthian columns are in the style of the late Roman Republic; it probably dates to Agrippa's first voyage to Gaul in 39 BC.[18]

- The Sacred Spring. The spring and its healing powers were the basis of the reputation and wealth of the town. Originally it was simply a basin carved into the rock. In the 2nd century BC it was covered by a stone building with a decorative facade of stones in a fishscale pattern. A stone stairway led from the spring up to the top of the nearby hill. In the 1st century AD the Roman legionnaire M. Licinius Verecundus built an altar to the right of the stairway, dedicated to the god Glanis, the Glannicae, and to Fortuna Redux, the goddess responsible for the safe return of those far from home. The inscription reads: "To the god Glanis, and the Glanicae, and to Fortuna Redux: Marcus Licinius Verecundus, of the tribe Claudia (an electoral district in Rome), veteran of the XXI Legion Rapaces (Rapaces, or predators, was the nickname of the XXI Legion, which was serving at the time in Germany) - has accomplished his vow with gratitude and good faith." [19]

- The Chapel of Hercules. The remains of a small chapel devoted to Hercules, the guardian of springs, is located near the spring. Against the walls, the archeologist Henri Roland discovered six altars to Hercules, and the torso of a large statue of Hercules, 1.3 meters high, holding a vase of water, evidently the water of the Glanum spring. The inscription on the base of the statue indicates that it was placed in gratitude for the safe return of the tribune C. Licinius Macer, and the centurions and soldiers from Glanum from a campaign during the 2nd century AD.

Glanum in popular culture

In Robert Holdstock's fantasy novel Ancient Echoes, Glanum is a sentient, living, moving city which eventually settles at its present site in Provence.

Notes

- ↑ Claude Ptolémée, Book 2, Ch. 10, 8 (p. 146, line 26)

- ↑ Antonine Itinerary, 343.6

- ↑ Ravenna Cosmography, 4.28

- ↑ Tabula Peutingeriana

- ↑ Congès, Ann Roth, Glanum - De l'oppidum salyen a la cité latine, pg. 5

- ↑ Congès, Anne Roth, Glanum - De l'oppidum salyen à la cité latine, Editions d Patrimoine, Centre des Munuments Historique. Pg. 3

- ↑ Congés, pg. 7

- ↑ Congès, pg. 9.

- ↑ Smith, Norman (1971), A History of Dams, London: Peter Davies, ISBN 0-432-15090-0

- ↑ "Key Developments in the History of Arch Dams". Cracking Dams. SimScience. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Congès, pg. 17

- 1 2 Congès, pg. 21

- ↑ Congè (pg. 23)

- ↑ Congès, pg. 40.

- ↑ Congès, pg. 36.

- ↑ Congès, pg. 28-29

- ↑ Congès, pg. 32-33.

- ↑ Congès, pg. 55

- ↑ Congès, pg. 57.

References

- Congès, Anne Roth (2000), Glanum- De l"oppidum salyen à la cité latine, Paris: Editions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux, ISBN 978-2-7577-0079-2

- Hodge, A. Trevor (2000), "Reservoirs and Dams", in Wikander, Örjan, Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, Technology and Change in History, 2, Leiden: Brill, pp. 331–339, ISBN 90-04-11123-9

- Schnitter, Niklaus (1978), "Römische Talsperren", Antike Welt, 8 (2): 25–32 (31f.)

- Schnitter, Niklaus (1987a), "Verzeichnis geschichtlicher Talsperren bis Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts", in Garbrecht, Günther, Historische Talsperren, Stuttgart: Verlag Konrad Wittwer, pp. 9–20, ISBN 3-87919-145-X

- Schnitter, Niklaus (1987b), "Die Entwicklungsgeschichte der Bogenstaumauer", in Garbrecht, Günther, Historische Talsperren, Stuttgart: Verlag Konrad Wittwer, pp. 75–96, ISBN 3-87919-145-X

- Smith, Norman (1971), A History of Dams, London: Peter Davies, ISBN 0-432-15090-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glanum. |

- Site archéologique de Glanum - official site

- Official tourist office of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, both in French and in English. Contains information on Glanum.

- Locator map of Glanum (Michelin)

- Livius.org: Glanum (St.Rémy-de-Provence)