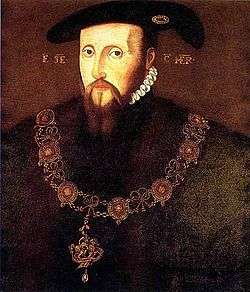

George Blagge

Sir George Blagge (1512 – 17 June 1551) was an English courtier, politician, soldier and a minor poet. He was the Member of Parliament for Bedford from 1545 to 1547, and Westminster from 1547 to 1551, during the reign of Edward VI.[1] His trial and condemnation for heresy in 1546 earned him a place in Protestant martyrology. His family surname was frequently rendered Blage by contemporaries, while another variant was Blake.

Early life and education

Blagge was the younger of two sons[2] of Mary Brooke and Robert Blagge.[3]

- Robert Blagge was an Exchequer Baron[1] – an important post in a court dealing mainly with equity cases. He had prospered in the Tudor administration and owned land in several parts of England:in the south-west in rural Somerset and at Bristol; near London at Holloway and Westminster in Middlesex; and in the south-east, especially at Dartford in Kent.[2]

- Mary Brooke was the daughter of John Brooke, 7th Baron Cobham of Cobham, Kent, an important landowner in the vicinity of Blagge's Kent holdings. Her sister, Alelye, was Robert Blagge's first wife. She was his second wife and married him in 1506.[3] George was born about six years later.

George's father, Robert, died in 1522. He left George the use of his lands in the south-west and at Holloway, as well as two houses at Dartford. The elder son took the property in Westminster, but it seems that George later moved there and he was described as "of Westminster and Dartford" in later life.[2]

George Blagge was educated at Cambridge.[1]

Early career

As with many minor member of the landed gentry, Blagge's early career consisted mainly of a search for patronage from a great man who might provide openings and opportunities for advancement. However, he was unfortunate in his choice of patrons, the two most important of whom were involved in fatal or near-fatal political entanglements.

Initially he attached himself to Sir Thomas Wyatt, a rising Kent landowner who was married to a cousin of Blagge.[4] Wyatt was a few years older than Blagge and a client of Henry VIII's chief minister, Thomas Cromwell. Both a poet, though unpublished in his lifetime, and a diplomat, Wyatt was an important influence on Blagge, who sought to emulate his style and dabbled in poetry. It was probably with Wyatt that Blagge travelled in France and Germany in 1535-36.[2] Wyatt narrowly escaped with his head in 1536, when he was one of those rumoured to have had intercourse with Anne Boleyn. However, Cromwell's protection allowed him to emerge as Henry's resident ambassador to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1537, although his chances of high office in England were ruined.[4] Blagge accompanied him to France and Spain, and acted as diplomatic courier for him in 1539, returning to England with his dispatches from Toledo. Blagge repaid his patron by standing witness for him when he was accused of diplomatic misconduct 1541. Wyatt died in the following year, and 18 months later Blagge was granted the stewardship of the manor of Maidstone, which Wyatt had previously held.[2]

Blagge then attached himself to the Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, a friend of Wyatt and a distinguished poet. Surrey was the son and heir of Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, one of the most powerful magnates in the land. Blagge was the earl's senior by a few years and was not afraid to rebuke him for his erratic behaviour – notably when he rioted in London with Thomas Wyatt the Younger in February 1543, a jape that led the Privy Council to interview and imprison him. Later that year English forces under Sir John Wallop were sent to operate on the northern front of the Italian War of 1542–1546, moving out of the Pale of Calais to support Imperial forces in defence of the Low Countries. Blagge accompanied Surrey on the expedition. He and Sir George Carew were nearly killed by sniper fire when they were inspecting a forward trench at the siege of Landrecies, a town occupied by the French early in the campaign. Both Surrey and Blagge gained considerable credit from their courage in the fighting.

At some point before 1547,[2] probably through Surrey's influence and contacts, Blagge was made an esquire of the body, a member of the Privy Chamber of Henry VIII, who used to call him 'Pig'.[5]

MP for Bedford

Blagge was elected to Parliament by the borough of Bedford early in 1545. Both Bedford and Bedfordshire were dominated by a coterie of local gentry [6] – notably the Mordaunts, the Gascoignes and the St. Johns.[7] However, Sir Francis Bryan, another courtier who had been a friend of Wyatt, was the recorder of the borough. A consummate political fixer and a close intimate of the king, Bryan is thought to have arranged the election of five members during his period in office.[6] It is very likely that he arranged the election of Blagge, as well as of Henry Parker, the other member elected in 1545. Parker was a long-standing servant of Bryan and another member of the royal household.[8]

The parliament had been summoned on 1 December 1544 but did not assemble for its first session until almost a year later. It's deliberations were brief. When he was arrested in 1546, Blagge was an elected Member, but because Parliament was not in session, nor about to sit, according to the customs of the time he was not protected by parliamentary privilege.[2]

Heresy trial

Towards the end of Henry VIII's reign, Blagge attracted attention due to his sacramentarian beliefs about the Lord's Supper, denying the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. On 9 May 1546 Blagge was heard to deny the efficacy of the Mass, while walking home after church.[2] He was immediately summoned by Thomas Wriothesley, the Lord Chancellor. Despite his claims that it was a misunderstanding or the result of a trick, he was sent to Newgate Prison. His trial was held at the Guildhall. The prosecution witnesses were Sir Edward Littleton of Pillaton Hall and Sir Hugh Calverley. Littleton, a former and future MP for Staffordshire, was a known religious conservative who had nevertheless done well from the Dissolution of the Monasteries. He was an abrasive, acquisitive figure, who had a talent for making enemies in high places and was considered over-mighty in his own county.[9] Calverley, then the MP for Cheshire, had a long record of violence, poaching and rustling behind him, as well as before him. Their testimony nevertheless seems to have carried weight in this case, as Blagge was found guilty and sentenced to be burned for heresy the following Wednesday.

However, Blagge had friends in high places. The king had not heard of the proceedings until John Russell, the Lord Privy Seal, appealed to him on Blagge's behalf. Henry immediately issued a pardon, allowing Blagge to avoid execution.[5][10] and ordered Wriothesley to release him. According to John Foxe, Blagge was then summoned by the king:

- commyng after to the kynges presence: ah my pygge, sayth the kyng to hym (for so hee was wont to call hym). Yea sayd hee, if your Maiestie had not bene better to me then your Byshops were, your pygge had bene rosted ere this tyme.[11]

As Foxe makes clear, the affair seemed desperate at the time, as it coincided with the final act in the drama of Anne Askew, who was burnt for her sacramentarian beliefs after being prosecuted by Wriothesley. However, Blagge not only escaped but ultimately benefitted from royal attention. Six months later he was appointed comptroller of the petty custom in the port of London.[2]

Religious and political polarisation

It is unclear whether Blagge actually held the sacramentarian views attributed to him, and, if so, when and how he moved to an evangelical position. It is likely that it was at about this time that he married Dorothy Badby: the marriage is known to have occurred by 1548 and Blagge's children were still very young when he died in 1551. It is possible that this marked an important turn in his religious thinking. Dorothy remarried twice into radically Protestant families after 1551 and their son Henry grew up an outspoken Puritan.[12] However, the words imputed to him at his trial seem little more than a couple of weak jokes – one, which he denied uttering – raising the implications of a mouse nibbling the consecrated Host.[11] Foxe's point in including Blagge among his martyrs seems to be not that he was a Protestant hero, but that life was unsafe for everyone under Wriothesley's persecution. Hence Foxe presents his brief account of Blagge's trial as a light intermission in his tale of Anne Askew, a genuine Protestant martyr.

However, Blagge soon became seen as a spokesman for the Protestant cause because of a series of court appearances. The first of these was in the heraldic trial of Surrey in January 1547. The earl was accused of appropriating royal insignia, specifically the arms of St Edward the Confessor.[13] This was presented as symbolic of his designs on power. Norfolk was a stalwart religious conservative and had also been arrested on similar charges. The king had become convinced, or had convinced himself, that there was a wide-ranging Catholic plot to put the Howards in power, and this played well with the previously hard-pressed Evangelical faction at court – focussed on Queen Catherine Parr and the Seymours, the uncles of Henry's young son and heir Edward.

In court, Blagge averred that Surrey had often boasted of the power the Howards would wield after Henry's death, when Edward would require a regency. He had told Surrey, so he said, that "rather than it should come to pass that the prince should be under the government of your father or you, I would bide the adventure to thrust this dagger in you".[2] Blagge was one of more than twenty witnesses marshalled by the king to convict Surrey, but his testimony has always been considered decisive. Surrey was executed later in the month and Norfolk, his father, only escaped the block because Henry VIII died early on the day scheduled for his execution. Surrey was not much of a politician and even less of a Catholic zealot: his imprisonment in 1543 was partly for failing to keep the fast in Lent.[13] Blagge lent himself, whether from conviction or from convenience, to the idea that there was a conspiracy to deny the Evangelicals a predominance in the next reign and, coincidentally that he himself had been a minor victim of it. It is unclear whether this contest for power was a reality or an ex post facto construct.

Surrey addressed his old friend in one of his last works, a paraphrase of Psalm 73:

- But now, my BLAGE, my error well I see;

- Such goodly light king David giveth me.[14]

Significantly, the name Blage has replaced the word blame in earlier versions of the poem.

MP for Westminster

Blagge's trials and testimonies made him well-adapted to prosper under the regency regime that followed the death of Henry VIII on 28 January 1547. He was joint commissioner for the musters for the Scottish campaign of that year with Sir John Holcroft.[15] This was a part of the war known as the Rough Wooing that culminated in the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh. A gallant soldier, Blagge impressed Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, the Lord Protector, who knighted him on campaign.[2]

It was perhaps the support of Somerset that secured Blagge one of the Westminster borough seats in the Parliament that assembled in November 1547. However, Westminster had only recently acquired the right to representation and was initially dominated by the short-lived Diocese of Westminster.[16] MPs in the early decades were almost all local property owners and many were connected with the court or the administration. Blagge fits this brief, as does his colleague in that parliament, John Rede. Probably both had local leverage of their own.

The parliament lasted for most of Edward VI's reign, outliving many of its members, including Blagge. After his death, his seat was taken by Robert Nowell, a young lawyer and a client of William Cecil.

In the politics of the Protectorate

Blagge was a faithful supporter of the successive regency regimes. In 1548 he was called upon to testify against Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley, the Lord High Admiral of England and husband of Catherine Parr, Henry VIII's widow. Thomas was accused of promoting legislation to limit his brother Edward's powers as Protector. Blagge stated in evidence:

- The Lord Admiral ... said unto me, ‘Here is gear shall come amongst you, my masters of the Nether House, shortly’. ‘What is that, my Lord?’ said I. ‘Marry’, said he, ‘requests to have the King better ordered, and not kept close that no man may see him’, and so entered with sundry mislikings of my Lord Protector’s proceedings touching the bringing up of the King’s Majesty ... I said, ‘Who shall put this into the House?’ ‘Myself’, said he. ‘Why then’, said I, ‘you make no longer reckoning of your brother’s friendship if you propose to go this way to work’.[2]

Although his downfall was postponed, the Admiral's own rashness led him to attainder and execution in the following year, some months after Catherine Parr's death after childbirth.

In 1550 Blagge received a palpable reward for his loyalty in the form of property in Kent, mainly from the endowment of a chantry in Dartford, dissolved in one of the first acts of the new Protestant regime.

In 1551, after the fall of Somerset, Blagge was called upon to give evidence in proceedings against Stephen Gardiner, the bishop of Winchester and formerly Henry VIII's secretary and his chief adviser during the persecution of Protestants in the mid-1540s. He was able to testify that he had been offended by one of the bishop's sermons attacking the sacramentarian position some three years earlier – an ironic commentary on his own earlier troubles.

Poet

Blagge belonged to a circle of poets but his own poetry is considered poor.[2] His output was probably considerable but only about six poems survive, mainly on political themes. They include verse on Catherine Parr and Jane Seymour, although the best known is a mordant epitaph for on Wriothesley:

- Picture of pride; of papistry the plat:

- In whom Treason, as in a throne did sit;

- With ireful eye, aye glearing like a cat,

- Killing by spite whom he thought good to hit.

- This dog is dead ...

Blagge's most important contribution to English poetry was his habit of collecting his friends' poems. The result was the famous Blage manuscript, now MS D.2.7 in the library of Trinity College, Dublin. Rediscovered only in the 1960s, it widened the known oeuvre of Thomas Wyatt and his circle, although it overlaps considerably with another collection, the Devonshire manuscript.[17]

Death

George Blagge died on 17 June 1551 at Great Stanmore. He had bought a lease on the manor, formerly property of St Alban's Abbey, the year before, after the murder of the previous lessee.[18] It stood well outside and well above London. The final outbreak of the mysterious disease known as sweating sickness was raging and there were many victims in the court. Blagge was probably one of them. He had neglected to make a will, suggesting a sudden onset of illness. He left his two-year-old son, Henry, as his heir.

Personal life

Marriage

Blagge married Dorothy Badby or Badbye, who was probably considerably younger and outlived him by several decades: she was still alive in 1578.[19] Dorothy was the daughter of William Badby of Essex, a landowner who had been known to speculate in former monastic properties.[20] She was a maid of honour to Catherine of Aragon before she married Blagge.[21] She and Blagge are known to have had three children: a son and two daughters.[2]

After Blagge's death, Dorothy married Richard Goodrich of Bolingbroke,[22] formerly three times MP for Great Grimsby. Goodrick was a staunch Protestant, active in reforming many aspects of the Church of England under Edward VI, and he had taken part with Blagge in proceedings against Bishop Gardiner. He had been married to Mary Blagge or Blage or Blake but had obtained a divorce and separation from her. During the reign of Mary, she took action for the restitution of her conjugal rights and dowry, the latter case being heard by Gardiner in the Court of Chancery. Dorothy had two further children with Goodrich: Richard and Elizabeth. He died in 1562.

Dorothy then married Sir Ambrose Jermyn, an elderly, wealthy landowner and courtier of Rushbrooke, Suffolk, another staunch Protestant. He already had a large family by his first wife, Anne, but Dorothy bore Sir Ambrose a further daughter, Dorothy. Two of her children by Blagge, and one by Goodrich, married children of Sir Ambrose – a common arrangement among Elizabethan gentry. Sir Ambrose died in 1577, but his wife is known to have outlived him

Children

George Blagge and Dorothy Badby had the following issue:

- Henry Blagge, born about 1549,[12] a Puritan MP for Sudbury in the 1580s. He married his step-sister Hester Jermyn. He inherited land from the Jermyns and the site of Bury St Edmunds Abbey from the Badby family, as well as his father's lands.

- Judith Blagge, who married Sir Robert Jermyn, the eldest son and heir of Sir Ambrose, a radical Puritan politician.[23]

- Sir Thomas Jermyn, their eldest son, also an active politician, nevertheless supported Charles I in his conflict with parliament and lost large sums of money by making loans to him.[24]

- Susan, their youngest daughter, married Sir William Hervey, a more neutral politician.[25] They became ancestors of the Marquesses of Bristol, who retain the title Earl Jermyn.

References

- 1 2 3 "Blagge, George (BLG512G)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 S. T. Bindoff (editor). "The History of Parliament: Members 1509-1558 - BLAGGE, George (Author: Helen Miller)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- 1 2 "Exceso de Transferencia". Tudorplace.com.ar. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- 1 2 S. T. Bindoff (editor). "The History of Parliament: Members 1509-1558 - WYATT, Sir Thomas (Author: Helen Miller)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- 1 2 Patrick Fraser Tytler, England Under the Reigns of Edward VI and Mary, p. 146.

- 1 2 S. T. Bindoff (editor). "The History of Parliament: Constituencies 1509-1558 - Bedford (Author: N. M. Fuidge)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ S. T. Bindoff (editor). "The History of Parliament: Constituencies 1509-1558 - Bedfordshire (Author: N. M. Fuidge)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ S. T. Bindoff (editor). "The History of Parliament: Members 1509-1558 - PARKER, Henry (Author: N. M. Fuidge)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ S. T. Bindoff (editor). "The History of Parliament: Members 1509-1558 - LITTLETON, Edward (Authors: L. M. Kirk / A. D.K. Hawkyard)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ Agnes Strickland, Lives of the Queens of England, Volume 5, pp. 52–53.

- 1 2 "The Acts and Monuments Online, 1570 edition: A brief narration of the trouble of Syr george blage". John Foxe. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- 1 2 P.W. Hasler (editor). "The History of Parliament: Members 1558–1603 - BLAGGE, Henry (Author: J.H.)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- 1 2 "Encyclopedia Britannica 1911: Henry Howard, earl of Surrey". 1911encyclopedia.org. 2006-10-06. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ The Poems of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey at Google Books, p. 104

- ↑ S. T. Bindoff (editor). "Members 1509-1558 - HOLCROFT, Sir John (by 1498-1560) - Author: Alan Davidson". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ S. T. Bindoff (editor). "The History of Parliament: Constituencies 1509-1558 - Westminster (Author: A. D.K. Hawkyard)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ Daalder, Joost (1984): Wyatt Manuscripts and “The Court of Venus”, PDF document from Flinders Academic Commons, Flinders University.

- ↑ "Victoria County History: Middlesex, Volume 5: Great Stanmore - Manor and other estates". British-history.ac.uk. 2003-06-22. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ FamilySearch Community Trees - Person Person ID 129003, citing Arthur Roland Maddison: Lincolnshire Pedigrees (1902–1906), (Publications of the Harleian Society: Visitations, volumes 50-52, 55. 4 volumes. London: Harleian Society, 1902-1906), FHL book 942 B4h., vol. 51, p. 415.

- ↑ "Victoria County History: Berkshire, Volume 3: Moulsford". British-history.ac.uk. 2003-06-22. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ "Kathy Lynn Emerson (2008-13): A Who's Who of Tudor Women: B-Bl". Kateemersonhistoricals.com. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ S. T. Bindoff (editor). "The History of Parliament: Members 1509-1558 - GOODRICH (GODERICK), Richard (Author: T.M. Hofman)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ P.W. Hasler (editor). "The History of Parliament: Members 1558–1603 - JERMYN, Sir Robert (Author: N. M. Fuidge)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris (editor). "The History of Parliament: Members 1604–1629 - JERMYN (GERMAINE), Sir Thomas (Authors: John. P. Ferris / Rosemary Sgroi)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris (editor). "The History of Parliament: Members 1604–1629 - HERVEY, Sir William II (1586–1660) (Authors: John. P. Ferris / Rosemary Sgroi)". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ 'Hundred of Earsham: Brockdish', An Essay towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: volume 5 (1806), pp. 327–339.