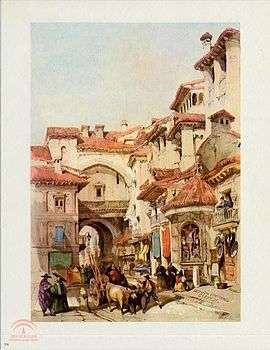

Gate of the Ears

The Gate of the Ears (in Spanish: Arco de las Orejas), also called Arc of the Ears or Bib-Arrambla gate, was a City Gate that was in the city of Granada (Andalusia, Spain). It was located at corner of plaza Bibrambla with calle Salamanca. The gate served as an access through the Walls protecting the city.

This was a Moorish arc, began to built in 11th and 12th centuries, and during 19th century was subject of enormous controversy in which it came to intervene the then highest authority of the state.

Part of remains of the monument were preserved. In 1935, Torres Balbás rebuilt an arc from the remains of the Gate of the Ears, without its vaults, in the Forest of the Alhambra. That, and the small alley to the start of Bib Rambla, are today the only vestiges that remaining.

Etymology

It was called by Spanish as Gate of the Ears. The main theory suggests that it was so called because of the habit of hanging in the gate, ears and other members of the criminals and evildoers who were condemned to death, after a probable execution in nearby Plaza de Bib-Rambla. But curiously it is not the only bloody legend or story there about the origin of its name. Another bloody story states in times of Philip IV of Spain, a tablao sunk overloaded with people, many people died in the misfortune, and many dead ladies were mutilated by hands of evils that advantage the confusion, stole the ladies's earrings and for it cut out them directly from the ears.[1]

But both one and other are just legends that is difficult to verify. Although not far from this gate was located the gate called Puerta Real, which names the city center, and itself it is shown in documents found in the Chancillería de Granada's archives, which was decapitated heads, hung on the gate, and in gate of Elvira, so that all citizens could see the heavy hand of justice.

This gate also was known in different periods, as Arc of the Ears, Bib-Arrambla gate, Gate of the Hands, Gate of the Pesos, Gate of the Horse, or Gate of the Sandland, this latter in times of Moorish occupation, area known by that name due the sand lands nearly Darro River, which vied horse racing. In Muslim era it was known as door Bab-Al-Rambla, there has derived the present name of the plaza. Another name with which it was known is the Gate of the Knifes, also seems to be related to the placement of such utensils that were confiscated or by the proximity of cutlery.

History and description

Its first construction dates from 11th-12th centuries, according to some recent studies indicating that based on the time of construction of the City Walls and the constructive characteristics compared with others of that period. It seems that served as an example for build others such as the 14th century's Gate of la Justicia (Yusuf I). Its similarity to those is the reason why some authors erroneously dated in Nasrid period.[2]

Formed part of an tower estimated in about 10–11 meters high, it was a monumental gate heavily protected by a square tower and three arches, where in its exterior front there was a large horseshoe arch, made with voussoirs of stone from Sierra Elvira. A balcony crowned the set in which, according to legend, it nailed the ears cut of the criminals of the city. It also had a machicolation, closed in 1507 forming what would be a chapel. Not being a military and defensive building itself had a more elegant line.[3] (as is also defined in the book "History of Granada" by Juan Gay Armenteros and Cristina Viñes Millet).

Inside there was an open space for the defense of the entrance and opposite a smaller arch with sunken and embossed voussoirs very similar to those of the Gate of the Justice in the Alhambra, so it can assume that both were built at the same time i.e. mid-14th century.

The importance of the arch is that, during both Moorish Spanish era, was the only entrance that had the Plaza de Bib Rambla, being surrounded by the City Walls.

The Catholic Monarchs put on the second arc a painting depicting Our Lady of the Rose, named after the flower that has the child, and whose sides are crowned the initials of the Kings. The kings placed there this canvas, possibly during one of their stays in the city and was installed a grandstand under the voussoirs of the first arc in 1507. This chapel was closed, leaving a hole to see from the plaza the image of the Virgin (as happened in a lot of Spanish gates, virgins were placed by the Catholic Monarchs), it was for Christianize the main elements of Muslim architecture, and show to everybody who enter, the new religion of the newly conquered city. Originally, this painting follows the schemes of the late Spanish-Flemish school. This Gothicism is most noticeable in the angels, smaller in size and angular wings. By contrast, in the faces of the Virgin and Child is appreciated an evolution towards greater naturalism and remarkable sweetness. Of the original folding of the tunic and the mantle barely left samples after restorations, but should be very rigid.[4]

In 1675 it made a tribune and an altar, which hid part of the original decoration. On the side of the plaza was read in Gothic characters on board of white marble an inscription alluding to a chapel that was above built in 1507 in honor for the fiestas of the Corpus Christi, by the chaplain of Queen Isabella I of Castile, to hear Mass the neighbors of the plaza and the Zacatín.

Demolition

In 1873, the Gate of the Ears was in poor condition. Thus, the Cabildo of Granada considered that was ruinous, also with the initiative of four businessmen and burghers of Granada who argued that it was a brake on economic development of the area and the city of Granada, joined to the trends of the ensanches/eixamples that alleged that the Walls constirpated cities, and announced its demolition.

The news caused such a stir that even the president himself of the First Republic demanded revocation of that order because "it would be a shame for Granada and a disgrace to the Republic, because the monuments of Granada are heritage of the human species".[5]

The then City council's architect Díaz Losada also opposed to the destruction and argued that the gate was not ruined, just needed some repairs. Instead, after the March 27, 1879, the architects of the Granada's City Council issued another report stating that restoration of the Gate of the Ears could be impossible, and there was only to dismantle its elements to restore it. The Madrid's answer again was clear: in 1881, the structure was declared 'National monument' to be under protection of the state.

But that did not help. Complaints were reproduced for several reasons: public health needs, place's urbanization or dangerous cracks in the building's structure. The 1884's summer was the lace to Gate of the Ears. The fear of a cholera epidemic caused to look bad the monument for its lack of cleanliness, so considered that could be focus of infection. Started its demolition on September 3, 1884.

Remains

Leopoldo Torres Balbás, a conservative architect of the Alhambra, was who try to rebuilt the gate in 1933, with only the original remains that were accumulated, placing the new arc in its current location. Unfortunately the rest of its original features were lost. He rise this remains, and this is located, almost hidden by foliage and trees, in the Forest of the Alhambra.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ "El Arco de las Orejas y la polémica nacional por su derribo", Ideal (newspaper)

- ↑ "Puerta de Bibarrambla (y Arco de las Orejas)", porlascallesdegranada.blogspot.com

- ↑ "El Arco de las Orejas y la polémica nacional por su derribo", Idel (newspaper)

- ↑ [lugaresdegranada.blogspot.com/2015/02/arco-de-las-orejas-puerta-de-bib-rambla.html "Arco de las Orejas, Puerta de Bib-rambla", lugaresdegranada.blogspot.com]

- ↑ "El Arco de las Orejas y la polémica nacional por su derribo", Ideal (newspaper)

- ↑ "A las puertas del cielo", Ideal (newspaper)