Gaineswood

|

Gaineswood | |

|

North facade in October 2011, after completion of an exterior renovation | |

| |

| Location |

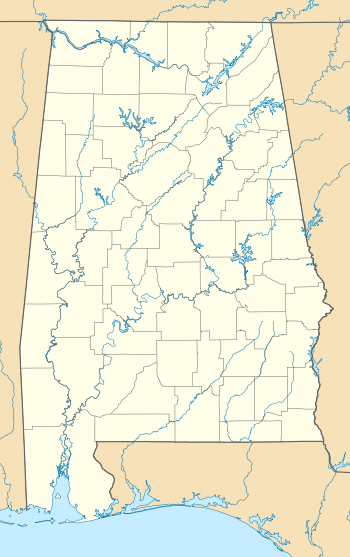

805 South Cedar Avenue Demopolis, Alabama |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 32°30′29.49″N 87°50′1.26″W / 32.5081917°N 87.8336833°WCoordinates: 32°30′29.49″N 87°50′1.26″W / 32.5081917°N 87.8336833°W |

| Built | 1843-61 |

| Architect | Nathan Bryan Whitfield |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| Website | www.gaineswood.org |

| NRHP Reference # | 72000167 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 5, 1972 [1] |

| Designated NHL | November 7, 1973 [2] |

Gaineswood is a plantation house in Demopolis, Alabama, United States. The house was completed on the eve of the American Civil War after a construction period of almost twenty years. It is the grandest plantation house ever built in Marengo County and is one of the most significant remaining examples of Greek Revival architecture in Alabama.[3] The house and grounds are currently operated by the Alabama Historical Commission as a historic house museum.

History

Gaineswood was designed and built by General Nathan Bryan Whitfield, beginning in 1843 as an open-hall log dwelling. Whitfield was a cotton planter who had moved from North Carolina to Marengo County, Alabama in 1834. In 1842 Whitfield bought the 480-acre (1.9 km2) property from George Strother Gaines, younger brother of Edmund P. Gaines.

The grounds had been the site of a notable historic event while owned by George Gaines. When Gaines was serving as the US Indian Agent, he is said to have met with the famous chief Pushmataha, of the Choctaw Nation, under an old post oak tree on what would become the Gaineswood estate. They were negotiating the terms of the treaty that would lead to the Choctaw removal to Indian Territory. The tree became known as the Pushmataha Oak.[4]

Whitfield first named the estate Marlmont in 1843; he renamed it Gaineswood in 1856 in honor of Gaines.[5] The Whitfield family tradition maintained that Gaines' original log house was the nucleus around which Whitfield had the mansion built, and that it was located at the present site of the south entrance hall and office.[6] Gen. Whitfield sold the house to his son, Dr. Bryan Watkins Whitfield, in 1861. The second generation of Whitfields maintained Gaineswood as a residence. Mary Foscue Whitfield inherited the nearby Foscue-Whitfield House in 1861 upon her father's death and used that as a residence as well.[5] In 1923 the Whitfield family sold Gaineswood. After years of use as a private residence, Gaineswood was purchased in 1966 by the state of Alabama from Dr. J.D. McLeod, for preservation as a house museum.[5]

Architecture

Gaineswood was completed in its current Greek Revival form in 1861. It is considered to be "Alabama's finest neoclassical house" [3] and one of America's most unusual neoclassical mansions. Gaineswood is one of the few Greek Revival homes in the United States that uses all three of the ancient Greek architectural orders: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. Built when tastes were shifting to the Italianate style, it features a partially asymmetrical layout.[7] Whitfield is known to have designed most of the house from pattern books by James Stuart, Minard Lafever, Nicholas Revett and others.[5] Much of the work on the house was executed by highly skilled artisan slaves.[6]

Exterior

The exterior has a decorative stucco over brick treatment, intended to simulate ashlar blocks. The exterior features the use of eighteen fluted Doric columns and fourteen plain square pillars to support the three porches, the main portico, and the porte-cochère. The assorted porches surround most of three sides of the structure. Parterre gardens off of the main north portico and south porch are surrounded by low masonry and wood balustrades and feature period-appropriate plantings and marble statuary. A rooftop observation ring with a vasiform balustrade surmounts the house and was used for observing the estate.[5]

The estate has three surviving outbuildings: a cook's house, a garden pavilion with eight fluted Corinthian columns, and a monumental gatehouse that date to the antebellum period. The tripartite entrance gate features massive pillars crowned by large metal finials and elaborate cast iron gates. The gatehouse and gates had to moved closer to the house as the city streets were widened in the 20th century.[4] No slave quarters were preserved, although some may have existed into the early 20th century for use as residences for workers on the plantation.

Interior

The interior features decorative plasterwork throughout the main floor. The library and the dining room both feature elaborate domed ceilings with central skylights. The hallway features fluted Ionic columns in the main entrance hall with reception rooms to either side, one for each sex.

The master's bedroom also features two fluted Ionic columns supporting a cornice that visually divides the room into bedroom and sitting room. The mistress' bedroom features a large floor-to-ceiling semicircular bay with curved windows and is fronted by two fluted Corinthian columns. Doors to either side of the bay provide access to the semicircular porch outside. The ballroom features four fluted Corinthian columns and twenty-four fluted Corinthian pilasters, vis-à-vis mirrors, an elaborate plaster cornice, and a coffered ceiling. The second floor is much simpler in decor and contains a boudoir, a nursery, and four large bedrooms.

Whitfield canal

Whitfield directed the digging of a drainage canal 1845 and 1863 to prevent water from overflowing and flooding the plantation. His slaves dug it by hand.[4] The rainfall on a large section of the Gaineswood estate originally had to follow a 17-mile (27 km) course to reach the Tombigbee River. About one mile (1.6 km) long, the canal was dug to a depth of more than 30 feet (9.1 m) deep through the underlying chalk in some areas; it quickly diverts the surface water into the river at Demopolis.[8]

Present

Gaineswood is on the National Register of Historic Places and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1973.[2][9] The estate is owned by the state of Alabama and is administered by the Alabama Historical Commission.[1] Severe moisture damage to the ceiling and dome in the dining room was corrected under a Save America's Treasures grant.[7]

The Whitfield family has donated or sold much of the original family furniture and some statuary to the Historical Commission to be used in the house. The Burning of the Eliza Battle, painted by Nathan B. Whitfield, still hangs at Gaineswood. He was a witness to the steamboat disaster in 1858.[10]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gaineswood. |

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Gaineswood". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-15.

- 1 2 Gamble, Robert Historic architecture in Alabama: a guide to styles and types, 1810-1930, page 76. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8173-1134-3.

- 1 2 3 Hammond, Ralph Ante-bellum Mansions of Alabama, pages 114-120. New York: Architectural Book Publishers, 1951. ISBN 0-517-02075-0

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marengo County Heritage Book Committee: The heritage of Marengo County, Alabama, page 18. Clanton, Alabama: Heritage Publishing Consultants, 2000. ISBN 1-891647-58-X

- 1 2 ""Gaineswood". "Alabama Historical Commission". Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- 1 2 "National Historic Landmarks Program". "Gaineswood". Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ↑ "Alabama Department of Archives and History". "Whitfield Canal Historical Marker". Archived from the original on 2007-08-21. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ↑ "Gaineswood Nomination" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination. National Park Service. 1971-09-13. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ↑ "The Burning of the Eliza Battle, (painting)". Art Inventories Catalog. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

External links

- Gaineswood.org

- Alabama Historical Commission: Gaineswood

- National Historic Landmark Nomination Photos of Gaineswood