Free-electron laser

A free-electron laser (FEL), is a kind of laser whose lasing medium consists of very-high-speed electrons moving freely through a magnetic structure,[1] hence the term free electron.[2] The free-electron laser is tunable and has the widest frequency range of any laser type,[3] currently ranging in wavelength from microwaves, through terahertz radiation and infrared, to the visible spectrum, ultraviolet, and X-ray.[4]

The free-electron laser was invented by John Madey in 1971 at Stanford University.[5] The free-electron laser utilizes technology developed by Hans Motz and his coworkers, who built an undulator at Stanford in 1953,[6][7] using the wiggler magnetic configuration which is one component of a free electron laser. Madey used a 43 MeV electron beam[8] and 5 m long wiggler to amplify a signal.

Beam creation

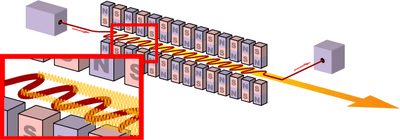

To create a FEL, a beam of electrons is accelerated to almost the speed of light. The beam passes through an undulator, a side to side magnetic field produced by a periodic arrangement of magnets with alternating poles across the beam path. The direction of the beam is called the longitudinal direction, while the direction across the beam path is called transverse. This array of magnets is called an undulator or a wiggler, because it forces the electrons in the beam to wiggle transversely along a sinusoidal path about the axis of the undulator.

The transverse acceleration of the electrons across this path results in the release of photons (synchrotron radiation), which are monochromatic but still incoherent, because the electromagnetic waves from randomly distributed electrons interfere constructively and destructively in time, and the resulting radiation power scales linearly with the number of electrons. If an external laser is provided or if the synchrotron radiation becomes sufficiently strong, the transverse electric field of the radiation beam interacts with the transverse electron current created by the sinusoidal wiggling motion, causing some electrons to gain and others to lose energy to the optical field via the ponderomotive force.

This energy modulation evolves into electron density (current) modulations with a period of one optical wavelength. The electrons are thus clumped, called microbunches, separated by one optical wavelength along the axis. Whereas conventional undulators would cause the electrons to radiate independently, the radiation emitted by the bunched electrons are in phase, and the fields add together coherently.

The FEL radiation intensity grows, causing additional microbunching of the electrons, which continue to radiate in phase with each other.[9] This process continues until the electrons are completely microbunched and the radiation reaches a saturated power several orders of magnitude higher than that of the undulator radiation.

The wavelength of the radiation emitted can be readily tuned by adjusting the energy of the electron beam or the magnetic-field strength of the undulators.

FELs are relativistic machines. The wavelength of the emitted radiation, , is given by [10]

- ,

or when the wiggler strength parameter K, discussed below, is small

- ,

where is the undulator wavelength (the spatial period of the magnetic field), is the relativistic Lorentz factor and the proportionality constant depends on the undulator geometry and is of the order of 1.

This formula can be understood as a combination of two relativistic effects. Imagine you are sitting on an electron passing through the undulator. Due to Lorentz contraction the undulator is shortened by a factor and the electron experiences much shorter undulator wavelength . However, the radiation emitted at this wavelength is observed in the laboratory frame of reference and the relativistic Doppler effect brings the second factor to the above formula. Rigorous derivation from Maxwell's equations gives the divisor of 2 and the proportionality constant. In an X-ray FEL the typical undulator wavelength of 1 cm is transformed to X-ray wavelengths on the order of 1 nm by ≈ 2000, i.e. the electrons have to travel with the speed of 0.9999998c.

Wiggler strength parameter K

K, a dimensionless parameter, tells the wiggler strength as the relationship between the length of a period and the radius of bend,[11]

where is the bending radius, is the applied magnetic field and the electron mass.

Quantum effects

In most cases, the theory of classical electromagnetism adequately accounts for the behavior of free electron lasers.[12] For sufficiently short wavelengths, quantum effects of electron recoil and shot noise may have to be considered.[13]

Large facilities required

Free-electron lasers require the use of an electron accelerator with its associated shielding, as accelerated electrons can be a radiation hazard if not properly contained. These accelerators are typically powered by klystrons, which require a high voltage supply. The electron beam must be maintained in a vacuum which requires the use of numerous vacuum pumps along the beam path. While this equipment is bulky and expensive, free-electron lasers can achieve very high peak powers, and the tunability of FELs makes them highly desirable in many disciplines, including chemistry, structure determination of molecules in biology, medical diagnosis, and nondestructive testing.

X-ray laser without mirrors

The lack of a material to make mirrors that can reflect extreme ultraviolet and x-rays means that FELs at these frequencies cannot use a resonant cavity like other lasers, which reflects the radiation so it makes multiple passes through the undulator. Consequently, in an X-ray FEL the output beam is produced by a single pass of radiation through the undulator; there must be enough amplification over a single pass to produce an adequately bright beam.

X-ray free electron lasers use long undulators. The underlying principle of the intense pulses from the X-ray laser lies in the principle of self-amplified spontaneous emission (SASE), which leads to the microbunching. Initially all electrons are distributed evenly and they emit incoherent spontaneous radiation only. Through the interaction of this radiation and the electrons' oscillations, they drift into microbunches separated by a distance equal to one radiation wavelength. Through this interaction, all electrons begin emitting coherent radiation in phase. All emitted radiation can reinforce itself perfectly whereby wave crests and wave troughs are always superimposed on one another in the best possible way. This results in an exponential increase of emitted radiation power, leading to high beam intensities and laser-like properties.[14] Examples of facilities operating on the SASE FEL principle include the Free electron LASer in Hamburg (FLASH), the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, the European x-ray free electron laser (XFEL) in Hamburg, the SPring-8 Compact SASE Source (SCSS), the SwissFEL at the Paul Scherrer Institute (Switzerland) and, as of 2011, the SACLA at the RIKEN Harima Institute in Japan.

Self seeding

One problem with SASE FELs is the lack of temporal coherence due to a noisy startup process. To avoid this, one can "seed" an FEL with a laser tuned to the resonance of the FEL. Such a temporally coherent seed can be produced by more conventional means, such as by high-harmonic generation (HHG) using an optical laser pulse. This results in coherent amplification of the input signal; in effect, the output laser quality is characterized by the seed. While HHG seeds are available at wavelengths down to the extreme ultraviolet, seeding is not feasible at x-ray wavelengths due to the lack of conventional x-ray lasers. In late 2010, in Italy, the seeded-FEL source FERMI@Elettra [15] started commissioning, at the Sincrotrone Trieste Laboratory. FERMI@Elettra is a single-pass FEL user-facility covering the wavelength range from 100 nm (12 eV) to 10 nm (124 eV), located next to the third-generation synchrotron radiation facility ELETTRA in Trieste, Italy. The advent of femtosecond lasers has revolutionized many areas of science from solid state physics to biology.

In 2012, scientists working on the LCLS overcame the seeding limitation for x-ray wavelengths by self-seeding the laser with its own beam after being filtered through a diamond monochromator. The resulting intensity and monochromaticity of the beam were unprecedented and allowed new experiments to be conducted involving manipulating atoms and imaging molecules. Other labs around the world are incorporating the technique into their equipment.[16][17]

Applications

Medical

Surgery

Research by Glenn Edwards and colleagues at Vanderbilt University's FEL Center in 1994 found that soft tissues including skin, cornea, and brain tissue could be cut, or ablated, using infrared FEL wavelengths around 6.45 micrometres with minimal collateral damage to adjacent tissue.[18][19] This led to surgeries on humans, the first ever using a free-electron laser. Starting in 1999, Copeland and Konrad performed three surgeries in which they resected meningioma brain tumors.[20] Beginning in 2000, Joos and Mawn performed five surgeries that cut a window in the sheath of the optic nerve, to test the efficacy for optic nerve sheath fenestration.[21] These eight surgeries produced results consistent with the standard of care and with the added benefit of minimal collateral damage. A review of FELs for medical uses is given in the 1st edition of Tunable Laser Applications.[22]

Fat removal

Several small, clinical lasers tunable in the 6 to 7 micrometre range with pulse structure and energy to give minimal collateral damage in soft tissue were created. At Vanderbilt, there exists a Raman shifted system pumped by an Alexandrite laser.[23]

Rox Anderson proposed the medical application of the free-electron laser in melting fats without harming the overlying skin.[24] At infrared wavelengths, water in tissue was heated by the laser, but at wavelengths corresponding to 915, 1210 and 1720 nm, subsurface lipids were differentially heated more strongly than water. The possible applications of this selective photothermolysis (heating tissues using light) include the selective destruction of sebum lipids to treat acne, as well as targeting other lipids associated with cellulite and body fat as well as fatty plaques that form in arteries which can help treat atherosclerosis and heart disease.[25]

Biology

Exceptionally bright and fast X-rays can image proteins using a sheet just one molecule thick. This technique allows first-time imaging of proteins that do not stack in a way that allows imaging by conventional techniques, 25% of the total number of proteins. Resolutions of 0.8 nm have been achieved with pulse durations of 30 femtoseconds. To get a clear view, a resolution of 0.1–0.3 nm is required. The short pulse durations prevented the lasers from destroying the molecules. The bright, fast X-rays were produced at the Linac Coherent Light Source at SLAC. As of 2014 LCLS was the world's most powerful X-ray FEL.[26]

Military

FEL technology is being evaluated by the US Navy as a candidate for an antiaircraft and anti-missile directed-energy weapon. The Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility's FEL has demonstrated over 14 kW power output.[27] Compact multi-megawatt class FEL weapons are undergoing research.[28] On June 9, 2009 the Office of Naval Research announced it had awarded Raytheon a contract to develop a 100 kW experimental FEL.[29] On March 18, 2010 Boeing Directed Energy Systems announced the completion of an initial design for U.S. Naval use.[30] A prototype FEL system was demonstrated, with a full-power prototype scheduled by 2018.[31]

See also

- Bremsstrahlung

- Cyclotron radiation

- Electron wake

- Gyrotron

- International Linear Collider

- Synchrotron radiation

References

- ↑ Huang, Z.; Kim, K. J. (2007). "Review of x-ray free-electron laser theory". Physical Review Special Topics - Accelerators and Beams. 10 (3). Bibcode:2007PhRvS..10c4801H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.10.034801.

- ↑ "Southeastern Universities Research Association Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility". Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- ↑ F. J. Duarte (Ed.), Tunable Lasers Handbook (Academic, New York, 1995) Chapter 9.

- ↑ "New Era of Research Begins as World's First Hard X-ray Laser Achieves "First Light"". SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. April 21, 2009. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ↑ C. Pellegrini, The history of X-ray free electron lasers, The European Physical Journal H, October 2012, Volume 37, Issue 5, pp 659–708. http://www.slac.stanford.edu/cgi-wrap/getdoc/slac-pub-15120.pdf

- ↑ Motz, Hans (1951). "Applications of the Radiation from Fast Electron Beams". Journal of Applied Physics. 22 (5): 527. Bibcode:1951JAP....22..527M. doi:10.1063/1.1700002.

- ↑ Motz, H.; Thon, W.; Whitehurst, R. N. (1953). "Experiments on Radiation by Fast Electron Beams". Journal of Applied Physics. 24 (7): 826. Bibcode:1953JAP....24..826M. doi:10.1063/1.1721389.

- ↑ "Phys. Rev. Lett. 38, 892 (1977): First Operation of a Free-Electron Laser". Prl.aps.org. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ↑ Feldhaus, J.; Arthur, J.; Hastings, J. B. (2005). "X-ray free-electron lasers". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 38 (9): S799. Bibcode:2005JPhB...38S.799F. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/38/9/023.

- ↑ Neil, G.; Merminga, L. (2002). "Technical approaches for high-average-power free-electron lasers". Reviews of Modern Physics. 74 (3): 685. Bibcode:2002RvMP...74..685N. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.685.

- ↑ Robert Soliday (2006-09-05). "WIGGLER". Argon National laboratory.

- ↑ Fain, B.; Milonni, P. W. (1987). "Classical stimulated emission". Journal of the Optical Society of America B. 4: 78. Bibcode:1987JOSAB...4...78F. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.4.000078.

- ↑ Benson, S.; Madey, J. M. J. (1984). "Quantum fluctuations in XUV free electron lasers". AIP Conference Proceedings. 118. p. 173. doi:10.1063/1.34633.

- ↑ "XFEL information webpages". Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ "FERMI / HomePage". Elettra.trieste.it. 2013-10-24. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ↑ Amann, J.; Berg, W.; Blank, V.; Decker, F. -J.; Ding, Y.; Emma, P.; Feng, Y.; Frisch, J.; Fritz, D.; Hastings, J.; Huang, Z.; Krzywinski, J.; Lindberg, R.; Loos, H.; Lutman, A.; Nuhn, H. -D.; Ratner, D.; Rzepiela, J.; Shu, D.; Shvyd'ko, Y.; Spampinati, S.; Stoupin, S.; Terentyev, S.; Trakhtenberg, E.; Walz, D.; Welch, J.; Wu, J.; Zholents, A.; Zhu, D. (2012). "Demonstration of self-seeding in a hard-X-ray free-electron laser". Nature Photonics. 6 (10): 693. Bibcode:2012NaPho...6..693A. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2012.180.

- ↑ ""Self-seeding" promises to speed discoveries, add new scientific capabilities". SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. August 13, 2012. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ↑ Edwards, G.; Logan, R.; Copeland, M.; Reinisch, L.; Davidson, J.; Johnson, B.; MacIunas, R.; Mendenhall, M.; Ossoff, R.; Tribble, J.; Werkhaven, J.; O'Day, D. (1994). "Tissue ablation by a free-electron laser tuned to the amide II band". Nature. 371 (6496): 416. Bibcode:1994Natur.371..416E. doi:10.1038/371416a0.

- ↑ "Laser light from Free-Electron Laser used for first time in human surgery". Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ↑ Glenn S. Edwards et al., Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74 (2003) 3207

- ↑ MacKanos, M. A.; Joos, K. M.; Kozub, J. A.; Jansen, E. D. (2005). "Corneal ablation using the pulse stretched free electron laser". Ophthalmic Technologies XV. Ophthalmic Technologies XV. 5688. p. 177. doi:10.1117/12.596603.

- ↑ F. J. Duarte (12 December 2010). "6". Tunable Laser Applications, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6058-4.

- ↑ "Efficiency and Plume Dynamics for Mid-IR Laser Ablation of Cornea". 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ↑ "BBC health". BBC News. 2006-04-10. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ "Dr Rox Anderson treatment". Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ "Super-bright, fast X-ray free-electron lasers can now image single layer of proteins". KurzweilAI. doi:10.1107/S2052252514001444. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ↑ "Jefferson Lab FEL". Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ↑ "Airborne megawatt class free-electron laser for defense and security". Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ "Raytheon Awarded Contract for Office of Naval Research's Free Electron Laser Program". Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ "Boeing Completes Preliminary Design of Free Electron Laser Weapon System". Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- ↑ "Breakthrough Laser Could Revolutionize Navy's Weaponry". Fox News. 2011-01-20. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

Further reading

- Madey, John, "Stimulated emission of bremsstrahlung in a periodic magnetic field". J. Appl. Phys. 42, 1906 (1971)

- Madey, John, Stimulated emission of radiation in periodically deflected electron beam, US Patent 38 22 410,1974

- Boscolo, et al., "Free-Electron Lasers and Masers on Curved Paths". Appl. Phys., (Germany), vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 46–51, May 1979.

- Deacon et al., "First Operation of a Free-Electron Laser". Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 38, No. 16, Apr. 1977, pp. 892–894.

- Elias, et al., "Observation of Stimulated Emission of Radiation by Relativistic Electrons in a Spatially Periodic Transverse Magnetic Field", Phys. Rev. Lett., 36 (13), 1976, p. 717.

- Gover, "Operation Regimes of Cerenkov-Smith-Purcell Free Electron Lasers and T. W. Amplifiers". Optics Communications, vol. 26, No. 3, Sep. 1978, pp. 375–379.

- Gover, "Collective and Single Electron Interactions of Electron Beams with Electromagnetic Waves and Free Electrons Lasers". App. Phys. 16 (1978), p. 121.

- "The FEL Program at Jefferson Lab"

- Brau, Charles (1990). "Free-Electron Lasers". Boston: Academic Press, Inc.

- Paolo Luchini, Hans Motz, Undulators and Free-electron Lasers, Oxford University Press, 1990.

External links

- Lightsources.org

- FERMI, the new FEL at the ELETTRA synchrotron in Triest

- Free-Electron Laser Open Book (National Academies Press)

- The World Wide Web Virtual Library: Free-Electron Laser research and applications

- European XFEL

- PSI SwissFEL

- SPring-8 Compact SASE Source

- Electron beam transport system and diagnostics of the Dresden FEL

- The Free Electron Laser for Infrared eXperiments FELIX

- W. M. Keck Free Electron Laser Center

- Jefferson Lab's Free-Electron Laser Program

- Free-Electron Lasers: The Next Generation by Davide Castelvecchi New Scientist, January 21, 2006

- Airborne megawatt class free-electron laser for defense and security

- FERMI@Elettra Free-Electron Laser Project

- Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL)