European political party

| European Union |

This article is part of a series on the |

Policies and issues

|

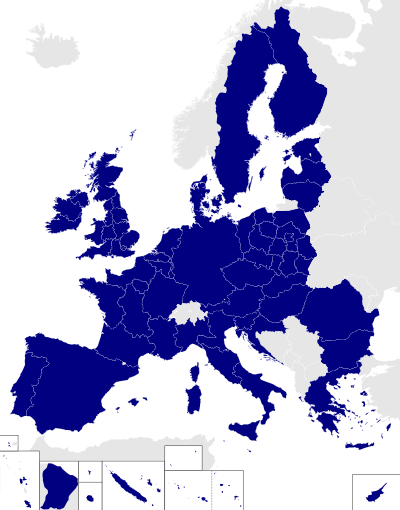

A European political party (formally, a political party at European level; informally a Europarty[1]) is a type of political party organisation operating transnationally in Europe and in the institutions of the European Union. They are regulated and funded by the European Union and are usually made up of national parties, not individuals. Europarties have the exclusive right to campaign during the European elections and express themselves within the European Parliament by their affiliated political groups and their MEPs. Europarties, through coordination meetings with their affiliated heads of state and government, influence the decision-making process of the European Council. Europarties also work closely and co-ordinate with their affiliated members of the European Commission and, according to the Lisbon Treaty the Europarty that wins the European elections has the right to nominate to the European Council its candidate for President of the European Commission.

The term "political party in the EU" can mean three different types of entities: domestic political parties, political groups in the European Parliament, and European political parties.[2]

Current Europarties

As of January 2016, there are 15 recognised Europarties:[3][4]

History

Timeline

1992

Section 41 of the Treaty of Maastricht[19] added Article 138a to the Treaty of Rome. Article 138a (later renumbered to Article 191) stated that "Political parties at European level are important as a factor for integration within the Union. They contribute to forming a European awareness and to expressing the political will of the citizens of the Union." So the concept of a "political party at European level" was born.

1997

Article J.18 and Article K.13 of the Treaty of Amsterdam[20] established who should pay for expenditure authorised by Article 138/191 within certain areas. This provided a mechanism whereby Europarties could be paid for out of the European budget, and the Europarties started to spend the money. Such expenditure included funding national parties, an outcome not originally intended.

2001

Article 2, section 19 of the Treaty of Nice[21] added a second paragraph to Article 191 of the Treaty of Rome. That paragraph stated that "The Council, acting in accordance with the procedure referred to in Article 251, shall lay down the regulations governing political parties at European level and in particular the rules regarding their funding." The reference to "Article 251" refers to co-decision, which meant the European Parliament had to be involved. So Europarty funding had to be regulated by the Council and the European Parliament, acting together.

2003

Regulation (EC) No 2004/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 November 2003[22] defined what a "political party at European level" actually was and specified that funding should not go to national parties, either directly or indirectly. This meant that European money should stay at the Europarty level and, as a result, the nascent Europarties started to organise themselves on a more European basis instead of acting as a mechanism for funding national parties.

2007

That regulation was later heavily amended by the Decision of the Bureau of the European Parliament of 29 March 2004[23] and by other amendments, the latest of which is Regulation (EC) No 1524/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2007[24] These amendments tightened up the procedures and funding and provided for the earlier-floated[25] concept of a "political foundation at European level". This meant that the Europarties can set up and fund legally separate affiliated think-tanks (the Eurofoundations) to aid them, although funding national parties remains forbidden. The revised regulation also gives Europarties the exclusive responsibility to campaign for the European elections and can use their funds for this purpose (their corresponding political groups of the European Parliament are strictly forbidden to campaign).

2014

Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1141/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014[26] overhauled the existing framework for European Political Parties and Foundations, including by giving them legal status, and establishes an Authority for the purpose of registering, controlling and imposing sanctions on European political parties and European political foundations. The Authority will be a body of the European Union.

This regulation repealed Regulation (EC) No 2004/2003, however the provisions of that regulation shall continue to apply for the 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 budget years. Although it came in to force on 24 November 2014, the regulations shall only apply from 1 January 2017. The Authority shall however be set up by 1 September 2016. European political parties and European political foundations registered after 1 January 2017 may only apply for funding under this Regulation for activities starting in the 2018 budget year or thereafter.

Defunct Europarties

- The Alliance of Independent Democrats in Europe, a loose association of Eurosceptics and nationalists, met the recognition threshold from 2006 to 2008.[27][28][29]

- The heterogeneous Alliance for Europe of the Nations, which included moderate nationalists, national conservatives and Eurosceptics, met the recognition threshold from 2004 to 2009.[27][28][29]

- The eurosceptic, national conservative, right populist Movement for a Europe of Liberties and Democracy was recognized from 2012 to 2016.

- On 1 November 2008 Declan Ganley had registered a company in Dublin called the Libertas Party Ltd.[30] Libertas applied for Europarty recognition which was briefly granted but then suspended following the disavowal of two of its candidates.

Organisation

Regulations

As of 1 November 2008, the regulation governing Europarties is Regulation (EC) No 2004/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 November 2003,[31] as later amended[32] under codecision (see above). According to that regulation's European Commission factsheet,[33] for a party to become a Europarty it must meet the following criteria:

- it must have legal personality in the Member State in which its seat is located.

- it must observe the founding principles of the European Union, namely the principles of liberty, democracy, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and the rule of law.

- it must have participated, or intend to participate, in elections to the European Parliament.

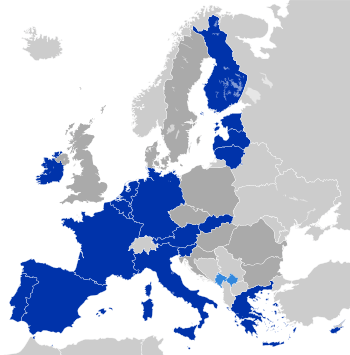

- it must have in at least one quarter of the Member States, one or both of the following:

- either it must have received at least 3% of the votes cast in each of those Member States at the most recent European Parliament elections.

- or it must already be represented by Members, whether Members of the European Parliament for those states, or Members of the national Parliaments of those states, or Members of the regional Parliaments of those states, or Members of the regional Assemblies of those states.

- it must publish its revenue and expenditure annually.

- it must publish a statement of its assets and liabilities annually.

- it must provide a list of its donors and their donations exceeding €500.

- it must not accept anonymous donations.

- it must not accept donations exceeding €12,000 per year and per donor.

- it must not accept donations from the budgets of political groups of the European Parliament.

- it must not accept more than 40% of a national political party's annual budget.

- it must not accept donations from any company over which the public authorities may exercise a dominant influence, either by virtue of their ownership of it, or by their financial participation therein.

- it must get at least 15% of its budget from sources other than its European Union funding.

- it must submit its application by 30 September before the financial year that it wants funding for.

Funding

The initial total funding for 2012 was €15 million pre-financing. A further 20% (18.9 million) was given later on in the next year after accounts are presented, with yet further €9.720 million pre-financing for the foundations.[27][28][34]

Structure

All current Europarties are mostly made up of national parties, Individual members MP or MEPS: MP's who are members of member parties can become members of the Europarty. Additionally, people can become individual members of the Europarty without having to join a national party first (e.g. Marian Harkin, who is an individual member of the European Democratic Party).

European political parties not recognised by the EU

- European Federalist Party: the pan-European party advocating for the creation of a true Europe-wide democracy in Europe based on an increased citizens' participation in European politics and on the principles of european federalism. It is present in 18 Countries.

- European Pirate Party: An association of Pirate Parties from across Europe.

- Newropeans: Political movement of citizens with democratisation of the EU as the main focus.

- European Party for Individual Liberty: Libertarian political party.

- Euro Animal 7: Animal rights party.

- Europe–Democracy–Esperanto

- Democracy in Europe Movement 2025: Left movement advocating a Europe-wide democracy based on social rights and parliamentarism and decentralization.

Defunct

- European National Front: Network of ultra-nationalist and far-right parties in Europe.

Alliances of national parties

Confederations, networks and alliances are not europarties.

- Nordic Green Left Alliance: Scandinavian socialists and greens.

- European Anticapitalist Left: Network of anticapitalist, mostly broad more radical left-wing parties in Europe.

- Liberal South East European Network: Balkan liberal parties.

- Initiative of Communist and Workers' Parties: Network of orthodox Communist parties in Europe; anti-revisionist and against Eurocommunist reforms.

Defunct

- Euronat : Right-wing nationalist parties, including the British National Party of the United Kingdom and the National Front of France.

- Movement for European Reform : Conservative and Atlanticist eurosceptics; springboard for the formation of European Conservatives and Reformists

- Platform for Transparency : Loose confederation of three independent MEPs; somewhat eurosceptic.

- European Democratic Union : Christian democratic and conservative parties.

Membership of Europarties by national party

Controversy

Europarty funding goes to Europarties and stays with Europarties: the funding cannot be used for the funding of other political parties and in particular national political parties.[31] National political parties disinclined from joining Europarties are thereby disadvantaged.[35] 25 Members of the European Parliament petitioned the European Court of Justice, arguing that this contravened the EU's stated values of pluralism and democracy. The case was rejected after eighteen months.[36][37] A closely related case fought by the French Front National, the Italian Lega Nord, and the Belgian Vlaams Blok (now Vlaams Belang) was appealed[38] and rejected.[39]

See also

- Parties in the European Council

- Political foundation at European level

- Category:European Parliament party groups

References

- ↑ Wolfram Nordsieck. "Parties & Elections in Europe". Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ Lelieveldt, Herman; Princen, Sebatiaan. "The politics of the European Union". Google Books. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "Grants from the European Parliament to political parties at European level 2016", January 2016, from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/, retrieved January 2016

- ↑ http://www.europarl.europa.eu/pdf/grants/Annual_reports_parties_01-2016.pdf

- 1 2 Parties and Elections in Europe: The database about parliamentary elections and political parties in Europe, by Wolfram Nordsieck

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Demetriou, Kyriakos (2014). The European Union in Crisis : Explorations in Representation and Democratic Legitimacy. Springer. p. 46. ISBN 9783319087740.

- ↑ Baker, David; Schnapper, Pauline. Britain and the Crisis of the European Union. Springer. p. 87. ISBN 9781137005205.

- ↑ Nunes Silva, Miguel. "Europe Turns Against the EU". The American Conservative. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 FitzGibbon, John; Leruth, Benjamin; Startin, Nick. Euroscepticism as a Transnational and Pan-European Phenomenon : The Emergence of a New Sphere of Opposition. p. 198. ISBN 9781317422501.

- 1 2 http://www.european-left.org/sites/default/files/final_platform_en_7.pdf

- 1 2 3 Kenealy, Daniel; Peterson, John; Corbett, Richard (2015). The European Union: How does it work? (4 ed.). OUP Oxford. p. 155. ISBN 0199685371.

- ↑ Nathalie Brack; Olivier Costa (2014). How the EU Really Works. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-4724-1465-6.

- ↑ "The Kremlin 'hosts' the European extreme right". OSW. 2015-03-25. Retrieved 2016-03-15.

- ↑ "To Russia with love, from Europe's far-right fringe". FT.com. 2015-03-22. Retrieved 2016-03-15.

- ↑ "European Parliament Criticized for Funding Pro-Russian Peace Association". Sputnik News. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ "MEPs condemn €600,000 EU grant for far-right bloc - BBC News". BBC. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ Kumar, Ravi. Neoliberalism, Critical Pedagogy and Education. Routledge. ISBN 9781317335177.

- ↑ Wodak, Ruth; Richardson, John E. Analysing Fascist Discourse: European Fascism in Talk and Text. Routledge. ISBN 9781135097240.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex - 11992M/TXT - EN - EUR-Lex". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex - 11997D/TXT - EN - EUR-Lex". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex - 12001C/TXT - EN - EUR-Lex". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex - 32003R2004 - EN - EUR-Lex". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex - 32004D0612(01) - EN - EUR-Lex". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Regulation (EC) No 1524/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2007.

- ↑ EU in drive to make Brussels more political euobserver.com 29 May 2007

- ↑ "Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1141/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 on the statute and funding of European political parties and European political foundations". Official Journal of the European Union. 22 October 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Previous elections". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Liste des subventions octroyées en 2005 / List of grants awarded in 2005". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Grants from the European Parliament to political parties at European level 2004-2011", 9 July 2011, from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/

- ↑ "Ganley registers Libertas as a European political party" from the Irish Times, Saturday 1 November 2008

- 1 2 "EUROPA". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex - 2007_130 - EN - EUR-Lex". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex - l33315 - EN - EUR-Lex". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Press Release IP/07/1953, Brussels, 18 December 2007 europa.eu

- ↑ Why I am going to the European Court hannan.co.uk

- ↑ Pan-European political parties hannan.co.uk

- ↑ Order of the Court of First Instance of 11 July 2005 in Case T-13/04: Jens-Peter Bonde and Others v European Parliament and Council of the European Union eur-lex.europa.eu

- ↑ Case C-338/05 P: Appeal brought on 19 September 2005 by le Front National and Others against the judgment delivered on 11 July 2005 by the Court of First Instance of the European Communities (Second Chamber) in Case T-17/04 between Le Front National and Others and the European Parliament and the Counsel of the European Union eur-lex.europa.eu

- ↑ "EUR-Lex - C2006/224/32 - EN - EUR-Lex". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

External links

- Video : Relations between parliamentary groups and political parties European NAvigator

- Parties' contact details

- The European Parliament and Supranational Party System Cambridge University Press 2002

- Results of the 2004 European Parliament elections by political party at European level