European windstorm

European windstorm is a name given to the strongest extratropical cyclones which occur across the continent of Europe.[2] They form as cyclonic windstorms associated with areas of low atmospheric pressure, sometimes starting as nor'easters off the New England coastline, that track across the North Atlantic Ocean towards western Europe. They are most common in the autumn and winter months. On average, the month when most windstorms form is January. The seasonal average is 4.6 windstorms.[3] Deep low pressure areas are relatively common over the North Atlantic, sometimes starting as nor'easters off the New England coast, and frequently track past the north coast of Britain and Ireland and into the Norwegian Sea. However, when they track further south they can affect almost any country in Europe. Commonly affected countries include the United Kingdom, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, the Faroe Islands and Iceland, but any country in Central Europe, Northern Europe and especially Western Europe is occasionally struck by such a storm system.

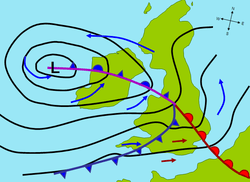

The strong wind phenomena intrinsic to European windstorms, that give rise to "damage footprints" at the surface, can be placed into three categories, namely the "warm jet", the "cold jet" and the "sting jet". These phenomena vary in terms of physical mechanisms, atmospheric structure, spatial extent, duration, severity level, predictability, and location relative to cyclone and fronts.[1]

On average these storms cause economic damage €1.9 billion per year, and insurance losses of €1.4 billion per year (1990–1998). They rank as the second highest cause of global natural catastrophe insurance loss (after U.S. hurricanes).[4]

Nomenclature

Naming of individual storms

Up to the second half of the 19th century, European windstorms were named after the person who spotted them. Usually, they would be named either by the year, the date, the Saint's day of their occurrence[5] or any other way that made them commonly known.

However, a storm may still be named differently in different countries. For instance, the Norwegian weather service also names independently notable storms that affect Norway,[6] which can result in multiple names being used in different countries they affect, such as:

- 1999 storm "Anatol" in Germany, is known as the "Decemberorkan" or "Adam" in Denmark and as "Carola" in Sweden.

- 2011 storm "Dagmar" in Norway and Sweden is known as "Patrick" in Germany and "Tapani" in Finland.

- 2013 St. Jude storm in the English media, is known as Christian in German and French (following the Free University of Berlin's Adopt-a-Vortex program) it was named Simone by the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute, and as the October storm in Danish and Dutch, it was later given the name Allan by the Danish Meteorological Institute following the political decision to name strong storms which affect Denmark.

An alternative Scottish naming system arose in 2011 via social media/Twitter which resulted in the humorous naming of Hurricane Bawbag[7][8][9] and Hurricane Fannybaws. Such usage of the term Hurricane is not without precedent, as the 1968 Scotland storm was referred to as "Hurricane Low Q".[10]

UK and Ireland

The UK Met Office and Irish forecasting service Met Éireann held discussions about developing a common naming system for Atlantic storms.[11][12] In 2015 a pilot project by the two forecasters was launched as "Name our storms" which sought public participation in naming large-scale cyclonic windstorms affecting the UK and or Ireland over the winter of 2015/16.[13][14] An independent forecaster, the European Windstorm Centre, also has its own naming list, although this is not an official list.[15]

Germany

During 1954, Karla Wege, a student at the Free University of Berlin's meteorological institute suggested that names should be assigned to all areas of low and high pressure that influenced the weather of Central Europe.[16] The university subsequently started to name every area of high or low pressure within its weather forecasts, from a list of 260 male and 260 female names submitted by its students.[16][17] The female names were assigned to areas of low pressure while male names were assigned to areas of high pressure.[16][17] The names were subsequently exclusively used by Berlin's media until February 1990, after which the German media started to commonly use the names, however, they were not officially approved by the German Meteorological Service Deutscher Wetterdienst.[16][18] The DWD subsequently banned the usage of the names by their offices during July 1991, after complaints had poured in about the naming system.[17] However, the order was leaked to the German press agency, Deutsche Presse-Agentur, who ran it as its lead weather story.[17] Germany's ZDF television channel subsequently ran a phone in poll on 17 July 1991 and claimed that 72% of the 40,000 responses favored keeping the names.[17] This made the DWD pause and think about the naming system and these days the DWD accept the naming system and request that it is maintained.[17][18]

During 1998 a debate started about if it was discrimination to name areas of high pressure with male names and the areas of low pressure with female names.[16] The issue was subsequently resolved by alternating male and female names each year.[16] In November 2002 the "Adopt-a-Vortex" scheme began, which allows members of the public or companies to buy naming rights for a letter chosen by the buyer that are then assigned alphabetically to high and low pressure areas in Europe during each year.[19] The naming comes with the slim chance that the system will be notable. The money raised by this is used by the meteorology department to maintain weather observations at the Free University.[4]

Name of phenomena

Several European languages use cognates of the word huracán (ouragan, orkan, huragan, orkaan, ураган, which may or may not be differentiated from tropical hurricanes in these languages) to indicate particularly strong cyclonic winds occurring in Europe. The term hurricane as applied to these storms is not in reference to the structurally different tropical cyclone of the same name, but to the hurricane strength of the wind on the Beaufort scale (winds ≥ 118 km/h or ≥ 73 mph).

In English, use of term hurricane to refer to European windstorms is mostly discouraged, as these storms do not display the structure of tropical storms. Likewise the use of the French term ouragan is similarly discouraged as hurricane is in English, as it is typically reserved for tropical storms only.[20][21] European windstorms in Latin Europe are generally referred to by derivatives of tempestas (tempest, tempête, tempestado), meaning storm, weather, or season, from the Latin, tempus meaning time.[22]

Globally storms of this type forming between 30° and 60° latitude are known as extratropical cyclones. The name European windstorm reflects that these storms in Europe are primarily notable for their strong winds and associated damage which can span several nations on the continent. The strongest cyclones are called windstorms within academia and the insurance industry.[2] The name European windstorm has not been adopted by the UK Met Office in broadcasts (though it is used in their academic research[23]) the media or by the general public, and appears to have gained currency in academic and insurance circles as a linguistic and terminologically neutral name for the phenomena.

In contrast to some other European nations there is a lack of a widely accepted name for these storms in English. The Met Office and UK media generally refer to these storms as severe gales.[24] The current definition of severe gales (which warrants the issue of a weather warning) are repeated gusts of 70 mph (110 km/h) or more over inland areas.[24] European windstorms are also described in forecasts variously as winter storms,[25] winter lows, autumnal lows, Atlantic lows and cyclonic systems. They are also sometimes referred to as bullseye isobars and dartboard lows in reference to their appearance on weather charts. A Royal Society exhibition has used the name European Cyclones.[26] with North-Atlantic Cyclone and North-Atlantic windstorms also being used.[2]

Cyclogenesis

North Atlantic Oscillation

The state of the North Atlantic Oscillation relates strongly to the frequency, intensity, and tracks of European windstorms.[27] An enhanced number of storms have been noted over the North Atlantic/European region during positive NAO phases (compared to negative NAO phases) and is due to larger areas of suitable growth conditions. The occurrence of extreme North Atlantic cyclones is aligned with the NAO state during the cyclones' development phase.[28] The strongest storms are embedded within, and form in large scale atmospheric flow.[29] It should be kept in mind that, on the other hand, the cyclones themselves play a major role in steering the NAO phase.[28] Aggregate European windstorm losses show a strong dependence on NAO,[30] with losses increasing/decreasing 10-15% at all return periods.[30]

Clustering

Temporal clustering of windstorm events has also been noted, with 8 consecutive storms hitting Europe during the winter of 1989/90. Lothar and Martin in 1999 were separated only by 36 hours. Kyrill in 2007 following only four days after Hanno, and 2008 with Johanna, Kirsten and Emma.[31][32] In 2011, Xaver (Berit) moved across Northern Europe and just a day later another storm, named Yoda, hit the same area. In December the same year, Friedhelm, Hergen, Joachim and Oliver/Patrick (Cato/Dagmar) struck northern Europe.

Economic impact

Insurance losses

Insurance losses from windstorms are the second greatest source of loss for any natural peril after Atlantic hurricanes in the United States.[33] Windstorm losses exceed those caused by flooding in Europe. For instance one windstorm, Kyrill in 2007, exceeded the losses of the 2007 United Kingdom floods.[34] On average, some 200,000 buildings are damaged by high winds in the UK every year.[35]

Energy supplies

European windstorms wipe out electrical generation capacity across large areas, making supplementation from abroad difficult (windturbines shut down to avoid damage and nuclear capacity may shut if cooling water is contaminated or flooding of the power plant occurs). Transmission capabilities can also be severely limited if power lines are brought down by snow, ice or high winds. In the wake of Cyclone Gudrun in 2005 Denmark and Latvia had difficulty importing electricity,[36] and Sweden lost 25% of its total power capacity as the Ringhals Nuclear Power Plant and Barsebäck nuclear power plant nuclear plants were shut down.[37]

During the Boxing Day Storm of 1998 the reactors at Hunterston B nuclear power station were shut down when power was lost, possibly due to arcing at pylons caused by salt spray from the sea.[38] When the grid connection was restored, the generators that had powered the station during the blackout were shut down and left on "manual start", so when the power failed again the station was powered by batteries for a short time of around 30 minutes, until the diesel generators were started manually.[38] During this period the reactors were left without forced cooling, in a similar fashion to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, but the event at Hunterston was rated as International Nuclear Event Scale 2.[38][39]

A year later in 1999 during the Lothar storm Flooding at the Blayais Nuclear Power Plant resulted in a "level 2" event on the International Nuclear Event Scale.[40] Cyclone Lothar and Martin in 1999 left 3.4 million customers in France without electricity, and forced EdF to acquire all the available portable power generators in Europe, with some even being brought in from Canada.[37] These storms brought a fourth of France's high-tension transmission lines down and 300 high-voltage transmission pylons were toppled. It was one of the greatest energy disruptions ever experienced by a modern developed country.[41]

Following the Great Storm of 1987 the High Voltage Cross-Channel Link between the UK and France was interrupted, and the storm caused a domino-effect of power outages throughout the Southeast of England.[42] Conversely windstorms can produce too much wind power. Cyclone Xynthia hit Europe in 2010, generating 19000 megawatts of electricity from Germany's 21000 wind turbines. The electricity produced was too much for consumers to use, and prices on the European Energy Exchange in Leipzig plummeted, which resulted in the grid operators having to pay over 18 euros per megawatt-hour to offload it, costing around half a million euros in total.[43]

Disruption of the gas supply during Cyclone Dagmar in 2011 left Royal Dutch Shell's Ormen Lange gas processing plant in Norway inoperable after its electricity was cut off by the storm. This left gas supplies in the United Kingdom vulnerable as this facility can supply up to 20 percent of the United Kingdom's needs via the Langeled pipeline, fortunately the disruption came at a time of low demand.[44] The same storm also saw the Leningrad Nuclear Power Plant also affected, as algae and mud stirred up by the storm were sucked into the cooling system, resulting in one of the generators being shut down.[45][46] A similar situation was reported in the wake of Storm Angus in 2016 (though not linked specifically to the storm) when reactor 1 at Torness Nuclear Power Station in Scotland was taken offline after a sea water intake tripped due to excess seaweed around the inlet.[47] Also following Storm Angus the UK's National Grid launched an investigation into whether a ship's anchor damaged four of the eight cables of the Cross Channel high voltage interconnector, which would leave it only able to operate at half of its capacity until February 2017.[48]

Notable windstorms

Historic windstorms

- Grote Mandrenke, 1362 – A southwesterly Atlantic gale swept across England, the Netherlands, northern Germany and southern Denmark, killing over 25,000 and changing the Dutch-German-Danish coastline.

- Burchardi Flood, 1634 – Also known as "second Grote Mandrenke", hit Nordfriesland, drowned about 8,000–15,000 people and destroyed the island of Strand.

- Great Storm of 1703 – Severe gales affect south coast of England.

- Night of the Big Wind, 1839 – The most severe windstorm to hit Ireland in recent centuries, with hurricane-force winds, killed between 250 and 300 people and rendered hundreds of thousands of homes uninhabitable.

- Royal Charter Storm, 25–26 October 1859 – The Royal Charter Storm was considered to be the most severe storm to hit the British Isles in the 19th century, with a total death toll estimated at over 800. It takes its name from the Royal Charter ship, which was driven by the storm onto the east coast of Anglesey, Wales with the loss of over 450 lives.

- The Tay Bridge Disaster, 1879 – Severe gales (estimated to be Force 10–11) swept the east coast of Scotland, infamously resulting in the collapse of the Tay Rail Bridge and the loss of 75 people who were on board the ill-fated train.[49]

- 1928 Thames flood, 6–7 January 1928 – Snow melt combined with heavy rainfall and a storm surge in the North Sea led to flooding in central London and the loss of 14 lives.

Severe storms since 1950

- North Sea flood of 1953 – Considered to be the worst natural disaster of the 20th century both in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, claiming over 2,500 lives.

- North Sea flood of 1962 – The Storm reached the German coast of the North Sea with wind speeds up to 200 km/h. The accompanying storm surge combined with the high tide pushed water up the Weser and Elbe, breaching dikes and caused extensive flooding, especially in Hamburg. 315 people were killed, around 60,000 were left homeless.

- Gale of January 1976 January 2–5, 1976 – Widespread wind damage was reported across Europe from Ireland to Central Europe. Coastal flooding occurred in the United Kingdom, Belgium and Germany with the highest storm surge of the 20th century recorded on the German North Sea coast.

- Great Storm of 1987 – This storm affected southeastern England and northern France. In England maximum mean wind speeds of 70 knots (an average over 10 minutes) were recorded. The highest gust of 117 knots (217 km/h) was recorded at Pointe du Raz in Brittany. In all, 19 people were killed in England and 4 in France. 15 million trees were uprooted in England.

- 1990 storm series – Between 25 January and 1 March 1990, eight severe storms crossed Europe including the Burns' Day storm (Daria), Vivian & Wiebke. The total costs resulting from these storms was estimated at almost €13 billion.[50]

- Braer Storm of January 1993 – the most intense storm of this kind on record.

- Lothar and Martin,[51] 1999 – France, Switzerland and Germany were hit by severe storms Lothar (250 kmh/160 mph), and Martin (198 kmh/123 mph). 140 people were killed during the storms. Lothar and Martin together left 3.4 million customers in France without electricity.[37] It was one of the greatest energy disruptions ever experienced by a modern developed country.[41] The total costs resulting from both storms was estimated at almost 19.2 billion $US.

- Kyrill,[52] 2007 – Storm warnings were given for many countries in western, central and northern Europe with severe storm warnings for some areas. At least 53 people were killed in northern and central Europe, causing travel chaos across the region.

- Xynthia,[53] 2010 – A severe windstorm moved across the Canary Islands to Portugal and western and northern Spain, before moving on to hit south-western France. The highest gust speeds recorded at Alto de Orduña (228 km/h/ 142 mph). 50 people were reported to have died.[54]

Recent storms

- 2013–14 Atlantic winter storms in Europe in Europe saw a "conveyor belt" series of high-precipitation storms (mostly unexceptional for their winds) explosively deepened by a strong jet stream. The repeated formation of large deep lows over the Atlantic brought storm surges and large waves which coincided with some of the highest astronomical tides of the year and led to coastal damage. The low pressure areas brought heavy rainfalls and flooding, which became most severe over parts of England such as at the Somerset Levels.

See also

- Wind scales

References

- 1 2 Hewson, Tim D.; Neu, URS (2015-01-01). "Cyclones, windstorms and the IMILAST project". Tellus A. 67 (0). doi:10.3402/tellusa.v67.27128.

- 1 2 3 Martínez-Alvarado, Oscar; Suzanne L Gray; Jennifer L Catto; Peter A Clark (10 May 2012). "Sting jets in intense winter North-Atlantic windstorms" (PDF). Environmental Research Letters. 7 (2): 024014. Bibcode:2012ERL.....7b4014M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/2/024014. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ "Seasonal predictability of European wind storms" (PDF). Institute of Meteorology. Free University of Berlin. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- 1 2 "European Windstorms and the North Atlantic Oscillation: Impacts, Characteristics, and Predictability". RPI Series No. 2, Risk Prediction Initiative/Bermuda Biological Station for Research, Hamilton, Bermuda. 1999. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "Who, What, Why: How are hurricanes named?". BBC. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ "List of named extreme weathers in Norway". Meteolorologisk instituut. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ↑ "How internet sensation Hurricane Bawbag helped Scotland conquer the world". The Daily Record. 2011-12-09. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ↑ STEPHEN MCGINTY (2011-12-09). "Would Bawbag's proud progenitor please stand up and take a bow - Cartoon". Scotsman.com. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ↑ "Scots slang highlighted after country is battered by Hurricane Bawbag". Daily Record. 10 December 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ↑ Mr. Edward Heath, MP Bexley (7 February 1968). "Scotland (Storm Damage)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons.

- ↑ Ahlstrom, Dick (15 January 2015). "Storm-naming system yet to be put in place as Rachel peters out". Irish Times. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ↑ "Met Éireann plans to start naming storms from next year". The Journal. 21 December 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ↑ "Name our storms". Met Office. 19 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ "Met Éireann and the UK Met Office release list of winter storm names". Met Éireann. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ https://sites.google.com/site/europeanwindstormcenter/windstorm-names

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "History of Naming Weather Systems". The Free University of Berlin's Institute of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gutman, Roy. "Germany bans naming storms 'mean Irene' after howls of protest". The Ottawa Citizen. p. F10. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- 1 2 "Geschichte der Namensvergabe" [History of Naming Weather Systems]. The Free University of Berlin's Institute of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ↑ "European Cold Front 'Cooper' Sponsored by Mini". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ "Pas d'ouragan possible en France, mais des tempêtes comparables à Sandy". 20minutes.fr. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ "L'OUEST BALAYÉ PAR UN OURAGAN DÉVASTATEUR". alertes-meteo.com. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ American Heritage Dictionary

- ↑ "XWS: a new historical catalogue of extreme european windstorms" (PDF). Met Office. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- 1 2 Baker, Chris; Brian Lee (2008). "Guidance on Windstorms for the Public Health Workforce". Chemical Hazards and Poisons Report (13): 49–52. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ "Extratropical Cyclones (Winter Storms)". AIR worldwide. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ "Damaging winds from European cyclones". Royal Society. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Magnusdottir, Gudrun; Clara Deser; R. Saravanan (2004). "The Effects of North Atlantic SST and Sea Ice Anomalies on the Winter Circulation in CCM3. Part I: Main Features and Storm Track Characteristics of the Response". Journal of Climate. 17: 857–876. Bibcode:2004JCli...17..857M. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<0857:TEONAS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- 1 2 Donat, Markus G. (March 2010). "European wind storms, related loss potentials and changes in multi-model climate simulations" (PDF). Dissertation, FU Berlin. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ↑ Hanley, John; Caballero, Rodrigo (November 2012). "The role of large-scale atmospheric flow and Rossby wave breaking in the evolution of extreme windstorms over Europe" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (21). Bibcode:2012GeoRL..3921708H. doi:10.1029/2012GL053408. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- 1 2 "Impact of North Atlantic Oscillation on European Windstorms" (PDF). Willis Research Network. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ AIR Worldwide: European Windstorms: Implications of Storm Clustering on Definitions of Occurrence Losses

- ↑ European Windstorm Clustering Briefing Paper

- ↑ "Europe Windstorm" (PDF). RMS. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ↑ Doll, Claus; Sieber, N. (2010). "Climate and Weather Trends in Europe. Annex 1 to Deliverable 2: Transport Sector Vulnerabilities within the research project WEATHER (Weather Extremes: Impacts on Transport Systems and Hazards for European Regions) funded under the 7th framework program of the European Commission." (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ "The vulnerability of UK property to windstorm damage". Association of British Insurers. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Impacts of winter storm Gudrun of 7th –9th January 2005 and measures taken in Baltic Sea Region" (PDF). astra project. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Impacts of Severe Storms on Electric Grids" (PDF). Union of the Electricity Industry – EURELECTRIC. 2006. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Nuclear power station loss of electricity grid during severe storm (1998)" (PDF). safetyinengineering.com. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ "UK Nuclear alert at Scottish plant". BBC News. 30 December 1998. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ COMMUNIQUE N°7 – INCIDENT SUR LE SITE DU BLAYAIS ASN, published 30 December 1999, Retrieved 22 March 2011

- 1 2 Tatge, Yörn. "Looking Back, Looking Forward: Anatol, Lothar and Martin Ten Years Later". Air-Worldwide. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ Burt, S. D.; Mansfield, D. A. (1988). "The Great Storm of 15-16 October 1987". Weather. 43 (3): 90–108. Bibcode:1988Wthr...43...90B. doi:10.1002/j.1477-8696.1988.tb03885.x. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ "Smart Grid: Solving the Energy Puzzle" (PDF). T-Systems customer magazine, Best Practice. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ↑ "UK gas supplies choppy after North Sea storm". Reuters. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ↑ "Myrsky sulki generaattorin venäläisvoimalassa" (in Finnish). yle.fi. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ "Generator stängd vid Sosnovij Bor" (in Swedish). hbl.fi. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Hannan, Martin (23 November 2016). "Storms batter Scotland as reactor at Torness nuclear plant shuts down". The National. The National. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Ward, Andrew (29 November 2016). "UK grid loses half the power from link to France". www.ft.com. Financial Times. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Tay Bridge Disaster". Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ↑ "Storms European scale". European Centre for Climate Adaptation. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "1999 Windstorm naming lists". FU-Berlin. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "2007 Windstorm naming lists". FU-Berlin. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "2010 Windstorm naming lists". FU-Berlin. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ At least 50 dead in western Europe storms

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Northern Atlantic cyclones. |

- Met Office, University of Exeter & University of Reading: Extreme Wind Storms Catalogue

- Free University of Berlin low-pressure naming lists

- European Windstorm Centre, An unofficial independent forecaster