Eugene V. Debs

| Eugene Victor Debs | |

|---|---|

Debs in 1897 | |

| Member of the Indiana Senate from the 8th district | |

|

In office 1885–1889 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Eugene Victor Debs November 5, 1855 Terre Haute, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died |

October 20, 1926 (aged 70) Elmhurst, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party |

Democratic (1879–1894) Social Democracy (1897–1898) Social Democratic (1898–1901) Socialist (1901–1926) |

| Spouse(s) | Kate Metzel (m. 1885; his death 1926) |

| Profession | Fireman, grocer, trade unionist |

| Religion | Irreligious/Deist[1][2] |

| Signature |

|

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American union leader, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or the Wobblies), and five times the candidate of the Socialist Party of America for President of the United States.[3] Through his presidential candidacies, as well as his work with labor movements, Debs eventually became one of the best-known socialists living in the United States.

Early in his political career, Debs was a member of the Democratic Party. He was elected as a Democrat to the Indiana General Assembly in 1884. After working with several smaller unions, including the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, Debs was instrumental in the founding of the American Railway Union (ARU), one of the nation's first industrial unions. After workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company organized a wildcat strike over pay cuts in the summer of 1894, Debs signed many into the ARU. He called a boycott of the ARU against handling trains with Pullman cars, in what became the nationwide Pullman Strike, affecting most lines west of Detroit, and more than 250,000 workers in 27 states. To keep the mail running, President Grover Cleveland used the United States Army to break the strike. As a leader of the ARU, Debs was convicted of federal charges for defying a court injunction against the strike and served six months in prison.

In jail, Debs read various works of socialist theory and emerged six months later as a committed adherent of the international socialist movement. Debs was a founding member of the Social Democracy of America (1897), the Social Democratic Party of America (1898), and the Socialist Party of America (1901).

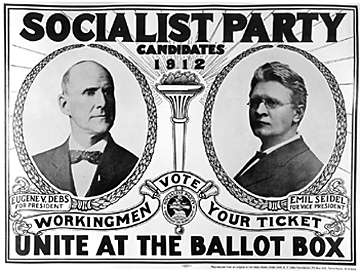

Debs ran as a Socialist candidate for President of the United States five times, including 1900 (earning 0.63% of the popular vote), 1904 (2.98%), 1908 (2.83%), 1912 (5.99%), and 1920 (3.41%), the last time from a prison cell. He was also a candidate for United States Congress from his native state Indiana in 1916.

Debs was noted for his oratory, and his speech denouncing American participation in World War I led to his second arrest in 1918. He was convicted under the Sedition Act of 1918 and sentenced to a term of 10 years. President Warren G. Harding commuted his sentence in December 1921. Debs died in 1926, not long after being admitted to a sanatorium due to cardiovascular problems that developed during his time in prison. He has since been cited as the inspiration for numerous politicians.

Biography

Early life

Eugene Debs was born on November 5, 1855, in Terre Haute, Indiana, to Jean Daniel and Marguerite Mari (Bettrich) Debs, who immigrated to the United States from Colmar, Alsace, France. His father, who came from a prosperous family, owned a textile mill and meat market. Debs was named after the French authors Eugene Sue and Victor Hugo.[4]

Debs attended public school, dropping out of high school at age 14.[5] He took a job with the Vandalia Railroad (1905–17) cleaning grease from the trucks of freight engines for fifty cents a day. He later became a painter and car cleaner in the railroad shops.[5] In December 1871, when a drunken locomotive fireman failed to report for work, Debs was pressed into service as a night fireman. He decided to remain a fireman on the run between Terre Haute and Indianapolis, earning more than a dollar a night for the next three and half years.[5]

In July 1875 Debs left to work at a wholesale grocery house, where he remained for four years,[5] while attending a local business school at night.[6]

Debs had joined the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (BLF) in February 1875 and became active in the organization. In 1877 he served as a delegate of the Terre Haute lodge to the organization's national convention.[5] Debs was elected associate editor of the BLF's monthly organ, Firemen's Magazine, in 1878. Two years later, he was appointed Grand Secretary and Treasurer of the BLF and editor of the magazine in July 1880.[5] He worked as a BLF functionary until January 1893 and as the magazine's editor until September 1894.[5]

At the same time he became a prominent figure in the community. He served two terms as Terre Haute's city clerk from September 1879 to September 1883.[5] In the fall of 1884 he was elected to the Indiana General Assembly as a Democrat, serving for one term.[6]

Marriage and family

Eugene Debs married Kate Metzel on June 9, 1885.[6] Their home still stands in Terre Haute, preserved amidst the campus of Indiana State University.

Labor activism

The railroad brotherhoods were comparatively conservative organizations, focused on providing fellowship and services rather than on collective bargaining. Debs gradually became convinced of the need for a more unified and confrontational approach as railroads were powerful companies in the economy. One influence was his involvement in the Burlington Railroad Strike of 1888, a defeat for labor that convinced Debs of the necessity of organizing along craft lines.[7]

After stepping down as Brotherhood Grand Secretary in 1893, Debs organized one of the first industrial unions in the United States, the American Railway Union (ARU), for unskilled workers. The Union successfully struck the Great Northern Railway in April 1894, winning most of its demands.

Pullman Strike

In 1894 Debs became involved in the Pullman Strike, which grew out of a compensation dispute started by the workers who constructed the train cars made by the Pullman Palace Car Company. The Pullman Company, citing falling revenue after the economic Panic of 1893, had cut the wages of its employees by 28%. The workers, many of whom were already members of the American Railway Union, appealed for support to the union at its convention in Chicago, Illinois.[3] Debs tried to persuade the Union members who worked on the railways that the boycott was too risky, given the hostility of both the railways and the federal government, the weakness of the union, and the possibility that other unions would break the strike. The membership ignored his warnings and refused to handle Pullman cars or any other railroad cars attached to them, including cars containing U.S. Mail.[8] After A.R.U. Board Director Martin J. Elliott extended the strike to St. Louis, doubling its size to 80,000 workers, Debs relented and decided to take part in the strike, which was now endorsed by almost all members of the ARU in the immediate area of Chicago.[9] On July 9, 1894, a New York Times editorial called Debs "a lawbreaker at large, an enemy of the human race."[10][11] Strikers fought by establishing boycotts of Pullman train cars, and with Debs' eventual leadership, the strike came to be known as "Debs' Rebellion".[4]

The U.S. federal government intervened, obtaining an injunction against the strike on the theory that the strikers had obstructed the U.S. Mail, carried on Pullman cars, by refusing to show up for work. President Grover Cleveland,[12] who Debs had supported in all three of his presidential campaigns, sent the United States Army to enforce the injunction. The entrance of the Army was enough to break the strike. Overall, 30 strikers were killed in the strike, 13 of them in Chicago, and thousands were blacklisted.[4][13]:154 An estimated $80 million worth of property was damaged, and Debs was found guilty of contempt of court for violating the injunction and sent to federal prison.[4]

Debs was represented by Clarence Darrow, later a leading American lawyer and civil libertarian, who had previously been a corporate lawyer for the railroad company. While it is commonly thought that Darrow "switched sides" to represent Debs, a myth repeated by Irving Stone's biography, Clarence Darrow For the Defense, he had in fact resigned from the railroad earlier, after the death of his mentor, William Goudy.[14] A Supreme Court case decision, In re Debs, later upheld the right of the federal government to issue the injunction.

Socialist leader

At the time of his arrest for mail obstruction, Debs was not yet a socialist. While serving his six-month term in the jail at Woodstock, Illinois, Debs and his ARU comrades received a steady stream of letters, books, and pamphlets in the mail from socialists around the country.[15]

Debs recalled several years later:

"...I began to read and think and dissect the anatomy of the system in which workingmen, however organized, could be shattered and battered and splintered at a single stroke. The writings of Bellamy and Blatchford early appealed to me. The Cooperative Commonwealth of Gronlund also impressed me, but the writings of Kautsky were so clear and conclusive that I readily grasped, not merely his argument, but also caught the spirit of his socialist utterance – and I thank him and all who helped me out of darkness into light."[15]

Additionally, Debs was visited in jail by Milwaukee socialist newspaper editor Victor L. Berger, who, in Debs' words, "came to Woodstock, as if a providential instrument, and delivered the first impassioned message of Socialism I had ever heard."[15] In his 1926 obituary in Time, it was said that Berger left him a copy of Das Kapital and "prisoner Debs read it slowly, eagerly, ravenously."[16] Debs emerged from jail at the end of his sentence a changed man. He would spend the final three decades of his life proselytizing for the socialist cause.

After Debs and Martin Elliott were released from prison in 1895, Debs started his Socialist political career. Debs persuaded the American Railway Union membership to join with the Brotherhood of the Cooperative Commonwealth to found the Social Democracy of America. Debs, along with Elliott, were the first federal office candidates for the fledgling Socialist party, running (unsuccessfully) for US president and Congress in 1900.[17] Along with his running mate Job Harriman, Debs received 87,945 votes – 0.6% of the popular vote – and no electoral votes.[18]

Debs' wife, Kate, was opposed to Debs' socialism.[19] The "tempestuous relationship with a wife who rejects the very values he holds most dear" was the basis of Irving Stone's biographical novel Adversary in the House.[20]

Split to found the Social Democratic Party

One year later this group split and Debs went with the majority faction to found the Social Democratic Party of the United States, also called the Social Democratic Party. Debs was elected chairman of the Executive Board of the National Council, the board which governed the party. But though the party did not have a sole figure that governed its actions, Debs' position as chairman and his notoriety gave him the status of party figurehead.[21] He was the Socialist Party of America candidate for president in 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920 (the final time from prison).

In his showing in the 1904 election, Debs received 402,810 votes, which was 2.98% of the popular vote. Debs received no electoral votes, and, with vice presidential candidate Benjamin Hanford, ultimately finished third overall.[22] In the 1908 election, Debs again ran on the same ticket as Benjamin Hanford. While receiving a slightly higher number of votes in the popular vote, 420,852, he received 2.83% of the popular vote. Again Debs received no electoral votes.[23] Debs received 5.99% of the popular vote (a total of 901,551 votes) in 1912, while his total of 913,693 votes in the 1920 campaign remains the all-time high for a Socialist Party candidate.[24] Running alongside Emil Seidel, Debs again received no electoral votes.[25]

Although he received some success as a third-party candidate, Debs was largely dismissive of the electoral process; he distrusted the political bargains that Victor Berger and other "Sewer Socialists" had made in winning local offices. He put much more value on organizing workers into unions, favoring unions that brought together all workers in a given industry over those organized by the craft skills workers practiced.

Founding the IWW

After his work with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and the American Railway Union, Debs' next major work in organizing a labor union came during the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). On June 27, 1905, in Chicago, Illinois, Debs and other influential union leaders including Big Bill Haywood, leader of the Western Federation of Miners, and Daniel De León, leader of the Socialist Labor Party, held what Haywood called the "Continental Congress of the working class". Haywood stated: "We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working class movement that shall have for its purpose the emancipation of the working class...",[26] and for Debs: "We are here to perform a task so great that it appeals to our best thought, our united energies, and will enlist our most loyal support; a task in the presence of which weak men might falter and despair, but from which it is impossible to shrink without betraying the working class."[27]

Socialists split with the IWW

Although the IWW was built on the basis of uniting workers of industry, a rift began between the union and the Socialist Party. It started when the electoral wing of the Socialist Party, led by Victor Berger and Morris Hillquit, became irritated with speeches by Haywood.[28] In December 1911, Haywood told a Lower East Side audience at New York's Cooper Union that parliamentary Socialists were "step-at-a-time people whose every step is just a little shorter than the preceding step." It was better, Haywood said, to "elect the superintendent of some branch of industry, than to elect some congressman to the United States Congress."[29] In response, Hillquit attacked the IWW as "purely anarchistic..."[30]

The Cooper Union speech was the beginning of a split between Bill Haywood and the Socialist Party, leading to the split between the factions of the IWW, one faction loyal to the Socialist Party, and the other to Haywood.[30] The rift presented a problem for Debs, who was influential in both the IWW and the Socialist Party. The final straw between Haywood and the Socialist Party came during the Lawrence Textile Strike when, disgusted with the decision of the elected officials in Lawrence, Massachusetts, to send police who subsequently used their clubs on children, Haywood publicly declared that "I will not vote again" until such a circumstance was rectified.[31] Haywood was purged from the National Executive Committee by passage of an amendment that focused on the direct action and sabotage tactics advocated by the IWW.[32] Debs was probably the only person who could have saved Haywood's seat.[33]

In 1906, when Haywood had been on trial for his life in Idaho, Debs had described him as "the Lincoln of Labor" and called for Haywood to run against Theodore Roosevelt for President of the United States,[34] but times had changed and Debs, facing a split in the Party, chose to echo Hillquit's words, accusing the IWW of representing anarchy.[35] Debs thereafter stated that he had opposed the amendment, but that once it was adopted it should be obeyed.[33] Debs remained friendly to Haywood and the IWW after the expulsion, despite their perceived differences over IWW tactics.[35]

Prior to Haywood's dismissal, the Socialist Party membership had reached an all-time high of 135,000. One year later, four months after Haywood was recalled, the membership dropped to 80,000. The reformists in the Socialist Party attributed the decline to the departure of the "Haywood element", and predicted that the party would recover. It did not; in the election of 1912 many of the Socialists who had been elected to public office lost their seats.[33]

Leadership style

Debs was noted by many to be a charismatic speaker who sometimes called on the vocabulary of Christianity and much of the oratorical style of evangelism – even though he was generally disdainful of organized religion.[36] It has been said, that Debs was what every socialist and radical should be; fierce in his convictions, but kind and compassionate in his personal relations.[37] As Heywood Broun noted in his eulogy for Debs, quoting a fellow Socialist: "That old man with the burning eyes actually believes that there can be such a thing as the brotherhood of man. And that's not the funniest part of it. As long as he's around I believe it myself."[38]

Although sometimes called "King Debs",[39] Debs himself was not wholly comfortable with his standing as a leader. As he told an audience in Detroit in 1906:[40]

I am not a Labor Leader; I do not want you to follow me or anyone else; if you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of this capitalist wilderness, you will stay right where you are. I would not lead you into the promised land if I could, because if I led you in, some one else would lead you out. You must use your heads as well as your hands, and get yourself out of your present condition.[13]:244

Political prisoner

Debs' speeches against the Wilson administration and the war earned the enmity of President Woodrow Wilson, who later called Debs a "traitor to his country."[41] On June 16, 1918, Debs made a speech in Canton, Ohio, urging resistance to the military draft of World War I. He was arrested on June 30 and charged with ten counts of sedition.[42]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

His trial defense called no witnesses, asking that Debs be allowed to address the court in his defense. That unusual request was granted, and Debs spoke for two hours. He was found guilty on September 12. At his sentencing hearing on September 14, he again addressed the court, and his speech has become a classic. Heywood Broun, a liberal journalist and not a Debs partisan, said it was "one of the most beautiful and moving passages in the English language. He was for that one afternoon touched with inspiration. If anyone told me that tongues of fire danced upon his shoulders as he spoke, I would believe it."[43]

Debs said in part:[44]

- Your honor, I have stated in this court that I am opposed to the form of our present government; that I am opposed to the social system in which we live; that I believe in the change of both but by perfectly peaceable and orderly means....

- I am thinking this morning of the men in the mills and factories; I am thinking of the women who, for a paltry wage, are compelled to work out their lives; of the little children who, in this system, are robbed of their childhood, and in their early, tender years, are seized in the remorseless grasp of Mammon, and forced into the industrial dungeons, there to feed the machines while they themselves are being starved body and soul....

- Your honor, I ask no mercy, I plead for no immunity. I realize that finally the right must prevail. I never more fully comprehended than now the great struggle between the powers of greed on the one hand and upon the other the rising hosts of freedom. I can see the dawn of a better day of humanity. The people are awakening. In due course of time they will come into their own.

- When the mariner, sailing over tropic seas, looks for relief from his weary watch, he turns his eyes toward the Southern Cross, burning luridly above the tempest-vexed ocean. As the midnight approaches the Southern Cross begins to bend, and the whirling worlds change their places, and with starry finger-points the Almighty marks the passage of Time upon the dial of the universe; and though no bell may beat the glad tidings, the look-out knows that the midnight is passing – that relief and rest are close at hand.

- Let the people take heart and hope everywhere, for the cross is bending, midnight is passing, and joy cometh with the morning.

Debs was sentenced on November 18, 1918, to ten years in prison. He was also disenfranchised for life.[3] Debs presented what has been called his best-remembered statement at his sentencing hearing:[45]

- Your Honor, years ago I recognized my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.

Debs appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court. In its ruling on Debs v. United States, the court examined several statements Debs had made regarding World War I and socialism. While Debs had carefully worded his speeches in an attempt to comply with the Espionage Act, the Court found he had the intention and effect of obstructing the draft and military recruitment. Among other things, the Court cited Debs' praise for those imprisoned for obstructing the draft. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. stated in his opinion that little attention was needed since Debs' case was essentially the same as that of Schenck v. United States, in which the Court had upheld a similar conviction.

Debs went to prison on April 13, 1919.[6] In protest of his jailing, Charles Ruthenberg led a parade of unionists, socialists, anarchists and communists to march on May 1 (May Day) 1919, in Cleveland, Ohio. The event quickly broke into the violent May Day Riots of 1919.

Debs ran for president in the 1920 election while in prison in Atlanta, Georgia, at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. He received 919,799[46] votes (3.4%),[47] slightly less than he had won in 1912, when he received 6%, the highest number of votes for a Socialist Party presidential candidate in the U.S.[6][48] During his time in prison, Debs wrote a series of columns deeply critical of the prison system. They appeared in sanitized form in the Bell Syndicate and were published in his only book, Walls and Bars, with several added chapters. It was published posthumously.[3]

In March 1919, President Wilson asked Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer for his opinion on clemency, offering his own: "I doubt the wisdom and public effect of such an action." Palmer generally favored releasing people convicted under the wartime security acts, but when he consulted with Debs' prosecutors – even those with records as defenders of civil liberties – they assured him that Debs' conviction was correct and his sentence appropriate.[49] The President and his Attorney General both believed that public opinion opposed clemency and that releasing Debs could strengthen Wilson's opponents in the debate over the ratification of the peace treaty. Palmer proposed clemency in August and October 1920 without success.[50]

At one point, Wilson wrote:

"While the flower of American youth was pouring out its blood to vindicate the cause of civilization, this man, Debs, stood behind the lines sniping, attacking, and denouncing them....This man was a traitor to his country and he will never be pardoned during my administration."[41]

In January 1921, Palmer, citing Debs' deteriorating health, proposed to Wilson that Debs receive a presidential pardon freeing him on February 12, Lincoln's birthday. Wilson returned the paperwork after writing "Denied" across it.[13]:405

On December 23, 1921, President Harding commuted Debs' sentence to time served, effective Christmas Day. He did not issue a pardon. A White House statement summarized the administration's view of Debs' case:

"There is no question of his guilt....He was by no means as rabid and outspoken in his expressions as many others, and but for his prominence and the resulting far-reaching effect of his words, very probably might not have received the sentence he did. He is an old man, not strong physically. He is a man of much personal charm and impressive personality, which qualifications make him a dangerous man calculated to mislead the unthinking and affording excuse for those with criminal intent."[51]

Last years

When Debs was released from the Atlanta Penitentiary, the other prisoners sent him off with "a roar of cheers" and a crowd of 50,000 greeted his return to Terre Haute to the accompaniment of band music.[52] En route home, Debs was warmly received at the White House by Harding, who greeted him by saying: "Well, I've heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet you personally."[53]

In 1924, Debs was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the Finnish Socialist Karl H. Wiik on the grounds that "Debs started to work actively for peace during World War I, mainly because he considered the war to be in the interest of capitalism."[54]

He spent his remaining years trying to recover his health which was severely undermined by prison confinement. In late 1926, he was admitted to Lindlahr Sanitarium in Elmhurst, Illinois.[3] He died there of heart failure on October 20, 1926, at the age of 70.[52] His body was cremated and buried in Highland Lawn Cemetery in Terre Haute, Indiana.[55]

Legacy

Eugene Debs helped motivate the American Left as a measure of political opposition to corporations and World War I. American socialists, communists, and anarchists honor his compassion for the labor movement and motivation to have the average working man build socialism without large state involvement.[56] Several books have been written about his life as an inspirational American socialist.

On May 22, 1962, Debs' home was purchased by the Eugene V. Debs Foundation for $9,500, which worked to preserve it as a Debs memorial was begun. In 1965 it was designated as an official historic site of the state of Indiana, and in 1966 it was designated as a National Historic Landmark of the United States. The preservation of the museum is monitored by the National Park Service. In 1990, the U.S. Department of Labor named Debs a member of its Labor Hall of Fame.[57]

While Debs did not leave a collection of papers to a university library, the pamphlet collection which he and his brother amassed is held by Indiana State University in Terre Haute. The scholar Bernard Brommel, author of a 1978 biography of Debs, has donated his biographical research materials to the Newberry Library in Chicago, where they are open to researchers.[58] The original manuscript of Debs' book Walls and Bars, with handwritten amendments, presumably by Debs, is held in the Thomas J. Morgan Papers in the Special Collections department of the University of Chicago Library.[59]

The town of Debs, Minnesota, is named after Debs.[60]

Former New York radio station WEVD (now ESPN radio) was named in his honor.[61]

"Debs Place", a housing block in Co-op City in the Bronx, New York, was named in his honor.[62]

The Eugene V. Debs Cooperative House in Ann Arbor, Michigan was named after Debs.[63]

There are at least two beers named after Debs - "Debs' Red Ale"[64] and "Eugene".[65]

Representation in other media

- John Dos Passos included Eugene Debs as a historical figure in his U.S.A. Trilogy. Debs is featured among other figures in the 42nd Parallel (1930). His affiliation with the IWW prompted actions by such fictional characters in the novel as "Mac".[66]

- Fifty Years Before Your Eyes (1950) is a documentary including historic footage of Debs, among others, directed by Robert Youngson.[67]

- The narrator of Hocus Pocus by Kurt Vonnegut is named Eugene Debs Hartke, in honor of Eugene V. Debs. (p. 1)

- Eugene Debs appears in the Southern Victory Series novels The Great War: Breakthroughs and American Empire: Blood and Iron by Harry Turtledove.

- Social Democrat Bernie Sanders voices Eugene Debs in a 1979 documentary about his political career.[68][69]

- The alternate history collection Back in the USSA by Kim Newman and Eugene Byrne is set in a world where Debs leads a Communist revolution in the USA in 1917.

Works

- Locomotive Firemen's Magazine (editor, 1880-1894) :Vol. 4 (1880) | Vol. 5 (1881) | Vol. 6 (1882) | Vol. 7 (1883) | Vol. 8 (1884) | Vol. 9 (1885) | Vol. 10 (1886) | Vol. 11 (1887) | Vol. 12 (1888) | Vol. 13 (1889) | Vol. 14 (1890) | Vol. 15 (1891) | Vol. 16 (1892) | Vol. 17 (1893) | Vol. 18 (1894)

- Debs: His Life, Writings, and Speeches: With a Department of Appreciations. Girard, KS: Appeal to Reason, 1908.

- Labor and Freedom. St. Louis: Phil Wagner, 1916. Audio version.

- Walls and Bars: Prisons and Prison Life In The "Land Of The Free." Chicago: Socialist Party, 1927.

See also

References

- ↑ Harold W. Currie (1972). The Religious Views of Eugene V. Debs. Mid-America. pp. p. 147–156.

- ↑ Annie Laurie Gaylor. "Eugene V. Debs". Freedom From Religion Foundation.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Eugene V. Debs". Time. November 1, 1926. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

As it must to all men, Death came last week to Eugene Victor Debs, Socialist

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Biographical: Eugene V. Debs," Railway Times [Chicago], vol. 2, no. 17 (Sept. 2, 1895), p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Eugene Victor Debs 1855–1926". Archived from the original on May 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the Gilded Age, edited by Leonard C. Schlup, James G. Ryan, page 405

- ↑ Latham, Charles. "Eugene V. Debs Papers, 1881–1940" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ↑ "Embracing More Railroads; Pullman Boycott Extending, The Men Being Determined. Big Lines West of Chicago Crippled by the Action of the Strikers, Who Will Endeavor to Bring in All Labor Organizations – Estimated that 40,000 of the Workers Are Out – May Change Headquarters to St. Louis – The Managers Stand Firm". The New York Times. June 29, 1894.

- ↑ The New York Times, July 9, 1894, pg. 4: "Organized labor" makes a miserable showing in its attempts to give aid and comfort to the Anarchists at Chicago....The truth is that every labor union man in the City of New-York knows that he becomes a criminal the moment he puts himself on the side of Debs or attempts to sustain Debs or attempts to sustain Debs by quitting work to show sympathy for the strikes and the riots Debs has provoked. When he sent his dispatch to the railway laborers in Buffalo Debs became a misdemeanant under the Penal Code of this State....He is a lawbreaker at large, an enemy of the human race. There has been quite enough talk about warrants against him and about arresting him. It is time to cease mouthings and begin. Debs should be jailed, if there are jails in his neighborhood, and the disorder his bad teaching has engendered must be squelched.

- ↑ Lindsey, Almont (1964) The Pullman strike: the story of a unique experiment and of a great labor p.312

- ↑ Chace, James. (2004). 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft & Debs-the election that changed the country. NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 80. ISBN 0-7432-0394-1.

- 1 2 3 Ray Ginger (1949). The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs. Rutgers University Press.

- ↑ John A. Farrell, Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned, 2011

- 1 2 3 Eugene V. Debs, "How I Became a Socialist." The Comrade, April 1902.

- ↑ "Eugene V. Debs. Obituary". Time. 8 (18). November 1926. p. 14.

- ↑ The Tribune almanac and political register edited by Horace Greeley, John Fitch Cleveland, F. J. Ottarson, Edward McPherson, Alexander Jacob Schem, Henry Eckford Rhoades

- ↑ "1900 Presidential General Election Results". Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ↑ Kate Debs seemed to have been so hostile to Debs's socialist activities – it threatened her sense of middle-class respectability – that novelist Irving Stone was led to call her, in the title of his fictional portrayal of the life of Debs, the Adversary in the House. (Daniel Bell, Marxian Socialism in the United States, footnote on page 88)

- ↑ Adversary in the House

- ↑ The Social Democracy of America Party History Marxist History. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ↑ 1904 Presidential General Election Results. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ↑ 1908 Presidential General Election Results. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ Chace, James (2005). 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debs – The Election that Changed the Country. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-7355-9.

- ↑ 1912 Presidential General Election Results. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood, 1929, by William D. Haywood, pp. 181.

- ↑ Eugene V. Debs Speech at the Founding of the IWW Documents for the Study of American History. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ↑ Peter Carlson, Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood. New York: W.W. Norton, 1983; pg. 156.

- ↑ Carlson, Roughneck, pg. 157.

- 1 2 Carlson, Roughneck, pg. 159.

- ↑ Carlson, Roughneck, pg. 183.

- ↑ Carlson, Roughneck, 200

- 1 2 3 Carlson, Roughneck, pg. 199.

- ↑ Carlson, Roughneck, pg. 109.

- 1 2 William D. Haywood, The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood. New York: International Publishers, 1929; pg. 279.

- ↑ Salvatore, Nick (1982). Eugene V. Debs:Citizen and Socialist. Illini Books.

- ↑ Gillespie, J. David. "Doctrinal Parties 1: The Socialists and Communists." Challengers to Duopoly: Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-party Politics. Columbia, SC:U of South Carolina, 2012. page 176. Print.

- ↑ Jesus and Eugene Debs Jim McGuiggan. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ↑ ""King" Debs". Harper's Weekly. July 14, 1894. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ↑ Learn About Eugene Debs Texas Labor. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- 1 2 Burl Noggle, Into the Twenties: The United States form Armistice to Normalcy (University of Illinois Press, 1974), 113

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/bio/zinn.htm

- ↑ David Pietrusza, 1920: The Year of Six Presidents. New York: Carroll and Graf, 2007; pp. 267–269.

- ↑ Pietrusza, 1920, pp. 269–270

- ↑ Statement to the Court Upon Being Convicted of Violating the Sedition Act Marxists. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ↑ Kennedy, David (2006). The American Pageant. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. p. 716.

- ↑ "Election of 1920". Travel and History. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ "Election of 1912". Travel and History. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ Stanley Coben, A. Mitchell Palmer: Politician (NY: Columbia University Press, 1963), 200–3

- ↑ Coben, 202

- ↑ "Harding Frees Debs and 23 Others Held for War Violations". New York Times. December 24, 1921. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- 1 2 "Eugene V. Debs Dies After Long Illness". New York Times. October 21, 1926. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ John Wesley Dean, Warren G. Harding (NY: Henry Holt, 2004) 128

- ↑ Nobel Foundation. "The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Peace, 1901–1955". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ↑ "Debs Foundation". Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Eugene V. Debs hero". Thirdworldtraveler.com. Retrieved 2010-03-08.

- ↑ "U.S. Department of Labor – Labor Hall of Fame – Eugene V. Debs". United States Department of Labor. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ↑ Alison Hinderliter,"Inventory of the Bernard J. Brommel-Eugene V. Debs Papers, 1886–2003", Roger and Julie Baskes Department of Special Collections, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois, 2004.

- ↑ Gerald Friedberg, "Sources for the Study of Socialism in America, 1901–1919," Labor History, vol. 6, no. 2 (Spring 1965), p. 161.

- ↑ "Tiny town of Debs draws big crowd to Fourth of July celebration". The Bemidji Pioneer. July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Louise M. Benjamin, Freedom of the Air and the Public Interest: First Amendment Rights in Broadcasting to 1935 (Southern Illinois University, 2001), 182

- ↑ Max Mitchell (February 17, 2011). "Glenn Beck disses Co-op City". Bronx Times.

- ↑ "Eugene V. Debs Cooperative House". Inter-Cooperative Council at the University of Michigan. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Debs' Red Ale". Bell's Beer. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Revolution-Eugene". ratebeer.com. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ Dos Passos, John. U.S.A. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1996

- ↑ Fifty Years before Your Eyes, IMDB

- ↑ "Bernie Sanders's Documentary on Eugene Debs". National Review Online. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ↑ Separation of Corporation and State (2015-07-26), Bernie Sanders - Eugene Debs Documentary - 1979, retrieved 2016-04-11

Further reading

- Bernard J. Brommel, "Debs's Cooperative Commonwealth Plan for Workers," Labor History, vol. 12, no. 4 (Fall 1971), pp. 560–569.

- Bernard J. Brommel, Eugene V. Debs: Spokesman for Labor and Socialism. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., 1978.

- Dave Burns, "The Soul of Socialism: Christianity, Civilization, and Citizenship in the Thought of Eugene Debs" in Labor, vol. 5, no. 2 (2008), pp. 83–116.

- Peter Carlson, Roughneck, The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood. New York: W.W. Norton, 1983.

- McAlister Coleman, Eugene V. Debs: A Man Unafraid. New York: Greenberg, 1930.

- J. Robert Constantine (ed.), Gentle Rebel: Letters of Eugene V. Debs. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

- J. Robert Constantine (ed.), Letters of Eugene V. Debs. In Three Volumes. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

- J. Robert Constantine and Gail Malmgreen (eds.) The Papers of Eugene V. Debs, 1834–1945: A Guide to the Microfilm Edition. Microfilming Corporation of America, 1983.

- Ray Ginger, The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs. Rutgers University Press: 1949.

- Herbert M. Morais and William Cahn, Eugene Debs: The Story of a Fighting American. New York: International Publishers, 1948.

- Ronald Radosh (ed.), Great Lives Observed: Debs. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1971.

- Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist. Reprinted by University of Illinois Press, 1984.

- Irving Stone. Adversary in the House. Doubleday: 1947.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Eugene Victor Debs |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eugene V. Debs. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Eugene V. Debs |

- Eugene V. Debs Foundation Museum and memorial in Deb's home from 1890 till death in 1926

- Works by Eugene V. Debs at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Eugene V. Debs at Internet Archive

- Works by Eugene V. Debs at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Eugene V. Debs Internet Archive, Marxists Internet Archive, www.marxists.org/ – Includes extensive collection of Debs' writings.

- Eugene V. Debs at DMOZ

- Eugene Debs on the IWW Memorial Page

- Other photos of Debs

- Historic film footage of Eugene Debs departing Atlanta penitentiary after presidential pardon, and exiting White House after visiting Harding

- Bernard J. Brommel - Eugene V. Debs Papers at the Newberry Library

- "Eugene Debs, Presidential Contender" from C-SPAN's The Contenders

- Bernie Sanders' 1979 Eugene Debs Documentary

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by — |

Socialist Party of America Presidential candidate 1900 (lost), 1904 (lost), 1908 (lost), 1912 (lost) |

Succeeded by Allan L. Benson |

| Preceded by Allan L. Benson |

Socialist Party of America Presidential candidate 1920 (lost) |

Succeeded by Robert M. La Follette, Sr. (Progressive Party) |