Esselen people

Esselen native c. 1791, by José Cardero | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

(Pre-contact c. 1700, est. 500-1200; As of 2003, about 460) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central Coast and Northern California | |

| Languages | |

| Esselen, English, and Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Catholic, traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Rumsen, Ohlone, and Salinan |

The Esselen are a Native American people belonging to a linguistic group in the hypothetical Hokan language family, who were indigenous in the Santa Lucia Mountains of the region now known as Big Sur in Monterey County, California. They lived seasonally on the coast and inland, surviving off the plentiful seafood during the summer and acorns and wildlife during the rest of the year. Experts estimate there were about 500 to 1200 individuals living in the steep, rocky region at the time of the arrival of the Spanish.

During the mission period of California history, Esselen children were baptized by the priests and at a certain age forcibly removed from their village and parents. Adult members of the Esselen tribe were forcibly conscripted and made to labor at the three nearby missions, Mission San Carlos, Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, and Mission San Antonio de Padua. Like many Native American populations, their members were decimated by disease, starvation, over work, and torture.

Historically, they were one of the smallest Native American populations in California and due to their proximity to three Spanish Missions they were likely one of the first whose culture was severely repressed as a result of European contact and domination.[1] They were assumed to have been exterminated but some tribal members avoided the mission life and emerged from the forest to work in nearby ranches in the early and late 1800s. Descendants of the Esselen are currently scattered, but many still live in the Monterey Peninsula area and nearby regions.

Origins

Archaeological and linguistic evidence indicates that the original people's territory once extended much farther north, into the San Francisco Bay Area, until they were displaced by the entrance of Ohlone people. Based on linguistic evidence, Richard Levy places the displacement at around AD 500.[2][3] Breschini and Haversat place the entry of Ohlone speakers into the Monterey area prior to 200 B.C. based on multiple lines of evidence. Carbon dating of excavated sites places the Esselen in the Big Sur since circa 2630 BCE.[4] Recently, however, researchers have obtained a radiocarbon date from coastal Esselen territory in the Big Sur River drainage dated prior to 6,500 years ago (archeological site CA-MNT-88).[5]

Etymology

The name Esselen probably derived from the name of a major native village, possibly from the village known as Exse'ein, or the place called Eslenes (the current site of the Mission San Carlos). The village name is likely derived from a tribal location known as Ex’selen, "the rock," which is in turn derived from the phrase Xue elo xonia eune, "I come from the rock."[6] "The Rock" may refer to the 361 feet (110 m) tall promontory, visible for miles both up and down the coast, on which the Point Sur Lighthouse is situated. It may also have referred to Pico Blanco, the mountain they believed that all life came from.

The Spanish extended the term to mean the entire linguistic group. Variant spellings exist in old records, including Aschatliens, Ecclemach, Eslen, Eslenes, Excelen, and Escelen.[7] "Aschatliens" may refer to a group around Mission San Carlos, in and around the village of Achasta.

Achasta was a Rumsen Ohlone village, and totally unrelated to the Esselen. Achasta was possibly founded only after the establishment of Mission San Carlos. It was the closest village to Mission San Carlos, and was 10+ miles from Esselen territory. "Eslenes" was nowhere near Mission San Carlos.

Language

The Esselen language is a language isolate. It is hypothetically part of the Hokan family. The language was spoken in the northern Santa Lucia Range. Prior to contact with European culture, there were between 500 and 1000 speakers.[8] La Pérouse, a French explorer, recorded 22 words in 1786. In 1792, Galiano, a Spanish ship's captain recorded 107 words and phrases. In 1832, Father Felipe Arroyo de la Cuesta recorded 58 words and 14 phrases at Soledad. The speakers were the Arroyo Seco area 15 miles (24 km) to the east. The Rumsen were fluent in Esselen and they provided some language. A total of about 300 words along with some short phrases have been identified. Examples include mamamanej (fire); koxlkoxl (fish); and ni-tsch-ekė (my husband).[9]:411ff The last known fluent speaker was Isabel Meadows who died in 1939.[10]

Locations

The Esselen resided along the upper Carmel and Arroyo Seco Rivers, and along the Big Sur coast from near present-day Hurricane Point to the vicinity of Vicente Creek in the south. Carbon dating tests of artifacts found near Slates Hot Springs, presently owned by Esalen Institute, indicate human presence as early as 3500 BC. With easy access to the ocean, fresh water and hot springs, the Esselen people used the site regularly, and certain areas were reserved as burial grounds. The Esselen's territory extended inland through the Santa Lucia Mountains as far as the Salinas Valley. In early times, they were hunter-gatherers who resided in small groups with no centralized political authority. The coastal area along the Central California coast between Carmel and San Luis Obispo is mostly rugged with high, steep cliffs and rocky shores, interrupted by small coastal creeks with occasional, small beaches.[11] The coastal Santa Lucia Mountains are very rugged except for the narrow canyons. This makes the area relatively inaccessible, long-term habitation a challenge, and limited the size of the native population.[11] Rainfall varies from 16 to 60 inches (410 to 1,520 mm) throughout the range, with the most on the higher mountains in the north; almost all precipitation falls in the winter. During the summer, fog and low clouds are frequent along the coast up to an elevation of several thousand feet. Surface runoff from rainfall events is rapid, and many streams dry up entirely in the summer, except for some perennial streams in the wetter areas in the north.[12]

Due to the relative abundance of food resources, the Esselen people never developed agriculture and remained hunter-gatherers.[13] They followed local food sources seasonally, living near the coast in winter, where they harvested rich stocks of mussels, limpets, abalone and other sea life. Inland they hunted deer and rabbits likely with bow and arrow, although no stone arrow points have been found. Arrows were of made of cane with and pointed with hardwood foreshafts. Their living sites commonly include bedrock mortars used to grind plant seeds and acorns.[14]

A large boulder, known as a bedrock mortar, is located in Apple Tree Camp on the southwest slope of Devil's Peak, north of the Camp Pico Blanco. More than 9 feet (2.7 m) across, it contains a dozen or more deep mortar bowls worn into it over several generations. The holes were hollowed out by Native Americans who used it to grind the acorns into flour. Other mortar rocks have also been found within the Pico Blanco Boy Scout camp at campsites 3 and 7, and slightly upstream from campsite 12, while a fourth is found on a large rock in the river, originally above the river, between campsites 3 and 4. Several Esselen mortars are located in boulders near Clover Basin Camp in Miller Canyon.[15]

Within the tribe's area at that time there were five distinct Esselen groups: Excelen, Eslenahan, Imunahan, Ekheahan, and Aspasniahan.[11] Each group had several villages that were occupied on a seasonal basis depending on the availability of resources such as food, water, shelter, and firewood.[11] In the summer and fall they moved inland to harvest acorns gathered from the Black Oak, Canyon Live Oak and Tanbark Oak, primarily on upper slopes above the narrow canyons.[15]

Culture

Archeological evidence of settlements have been found throughout Esselen territory. Artifacts found at a site in the Tassajara area (archaeological site CA-MNT-44) included bone awls, antler flakers, projectile points including desert side-notched points, and scrapers. Excavation at a second site at the mouth of the Carmel River (archaeological site CA-MNT-63) found more projectile points, a variety of cores and modified flakes, bone awls, a bone tube, a bone gaming piece, and mortars and pestles.[11] Many sites show aesthetic illustrations of numerous pictographs in black, white, and red.[14]

Dress and living standards

Prior to European contact, the people wore little clothing. The men were naked year-round and the women and girls may have worn a small apron. In cold weather they may have covered themselves with mud or rabbit or deerskin capes.[4] No evidence of sandals or foot wear have been found. Evidence of baskets have been found and were probably the principle item used to furnish households. Basket design included large conical baskets for carrying burdens, hemispherical-shaped cooking bowls, flat trays, and small boat-shaped baskets which may have been seed-beaters.[14] Pedro Fages described their dress in an account written before 1775:

Nearly all of them go naked, except a few who cover themselves with a small cloak of rabbit or hare skin, which does not fall below the waist. The women wear a short apron of red and white cords twisted and worked as closely as possible, which extends to the knee. Others use the green and dry tule interwoven, and complete their outfit with a deerskin half tanned or entirely untanned, to make wretched underskirts which scarcely serve to indicate the distinction of sex, or to cover their nakedness with sufficient modesty.[16]

Traders and sharers, they bartered acorns, fish, salt, baskets, hides and pelts, shells and beads. Their diet consisted primarily of acorns, which they first put through soaking to leach out the tannins and then cooked into a mush or baked as bread. From the Pacific, they caught and gathered fish, abalone, and mussels. And from the sloping, grassy Big Sur hills, they hunted deer.

There are virtually no contemporary records of the Esselen people's lives. Researchers believe that they lived in a manner very much like the Ohlone people to the north and the Costonoan people near present-day Monterey. Miguel Constanso, who traveled with Portola's expeditions 175 years later, wrote about the homes of the Indians who lived on the Santa Barbara Channel. He described how they lived in dome-shaped dwellings covered with bundled mats of tules. The homes were up to 55 feet (17 m) across and three or four families lived in a single dwelling. They built a fire pit in the middle and left a vent or chimney in the center of the roof.[17]:43 In mountainous regions where Redwood trees grew, they may have built conical houses from Redwood bark attached to a frame of wood. One of the main village buildings, the sweat lodge was low into the ground, its walls made of earth and roof of earth and brush. They built boats of tule to navigate on the bays propelled by double-bladed paddles.[18][19][20]

Spanish explorer Sebastian Viscaino reported,

Their food consists of seeds which they have in great abundance and variety, and of the flesh of game such as deer, which are larger than cows, and bear, and of neat cattle and bisons and many other animals.[17]

Spiritual beliefs

The Esselen left hand prints on rock faces in several locations, including the Pine Valley area and a site a few miles east of Tassajara where about 250 hand prints are located in a rock shelter and elsewhere in the Tassajara Valley.

The Esselen believed that because rocks held memory, when they put their hand into a hand that was carved on the rock, they could tune into everything that ever happened at the site. (This claim is not supported by the ethnographic literature.) The Esselen people gave names to everything, including individual trees, large rocks, paths, even different portions of a path. They believed everything, including the stars, moon, breeze, ocean, streams, trees, and rocks, were alive and had power, emotion, intelligence, and memory.[11]

A peak dominated by a prominent limestone cap named Pico Blanco splits the north and south forks of the Little Sur River. It was sacred in the native traditions of the Rumsien and the Esselen, who revered the mountain as a sacred place from which all life originated.[21] Although widely cited currently, no references to this mountain being sacred can be found in the early ethnographic literature.

European contact

Viscaino, likely the first European to land on the Central Coast of California, wrote about his visit to Monterey Bay from December 16, 1602 to January 3, 1603.

The Indians are of good stature and fair complexion the women being somewhat less in size than the men and of pleasing countenance. The clothing of the people of the coast lands consist of the skins of the sea-wolves [sea otters] abounding there, which they tan and dress better than is done in Castile; they possess also, in great quantity, flax like that of Castile, hemp and cotton, from which they make fishing-lines and nets for rabbits and hares. They have vessels of pine wood very well made, in which they go to sea with fourteen paddle men on a side, with great dexterity, even in stormy weather."[17]

Father Junipero Serra first established the original mission in Monterey on June 3, 1770, near the native village of Tamo. In May 1771, the viceroy approved Serra's petition to relocate the mission to its current location near the Carmel River and present-day town of Carmel-by-the-Sea[22] and named it Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo. Serra's goal was to put some distance between the mission's neophytes and the Presidio of Monterey. The Presidio was the headquarters of Pedro Fages, who served as military governor of Alta California between 1770 and 1774.

Fages worked his men very harshly and complaints mounted until Serra intervened.[23] He told Fages that, as a Christian, he had to observe the sabbath and let his men rest on Sundays.[24] But the soldiers raped the Indian woman and took them as concubines. At Serra's urging, Fages punished some of the more excessive incidents of sexual abuse, but it did not stop.[23] Fages and Serra were engaged in a heated power struggle.[25]

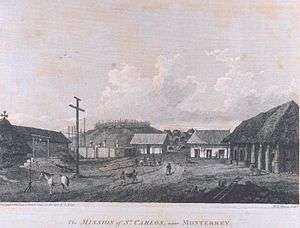

Spanish missions

Serra obtained permission to move the mission over the peninsula to near the Carmel River, distant from Fages and his troops and on land more suitable for farming. The new mission was within a short distance of the Rumsen Ohlone villages of Tucutnut and Achasta.[11] The latter village may have been founded after Mission San Carlos was relocated to Carmel. The mission was about 10 miles (16 km) from the nearest Esselen territory, Excelen.[11] On May 9, 1775, Junípero Serra baptized what appears to be the first Esselen, Pach-hepas, who was the 40-year-old chief of the Excelen. His baptism took place at Xasáuan, 10 leagues (about 26 miles (42 km)) southeast of the mission, in an area now named Cachagua, a close approximation of the Esselen name.

Baptisms and forced labor

King Charles V of Spain issued the New Laws (in Spanish, Leyes Nuevas, or "New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians") on November 20, 1542. These were replaced around the beginning of the 17th century with Repartimiento, which entitled a Spanish settler or official to the labor of a number of indigenous workers on their farms or mines. The Spanish state based its right over the land and persons of the Indies on the Papal charge to evangelize the indigenous population. This motivated the Jesuits to build missions across California.[26]

Under Spanish law, the Esselen were technically free men, but they could be compelled by force to labor without pay. With the help of the soldiers who guarded the mission, the Esselen and Ohlone Indians who lived near the mission were forcibly relocated, conscripted, and trained as plowmen, shepherds, cattle herders, blacksmiths, and carpenters on the mission. Disease, starvation, over work, and torture decimated the tribe.[27]:114

The Esselen had ongoing conflicts with the neighboring Rumsen tribe over crops and hunting grounds. The Rumsen initially assisted the Franciscans and when they fell on hard times, taught the missionaries what they could harvest from the wild for food.[28] When a tribal member entered Mission San Carlos to be baptized, the priests tried to communicate to them that they could not leave the mission and wander the forests and fields on their own as they had done before. They became in effect vassals of the mission. They were given a new Christian name at their baptism as well. If an Indian left the mission and attempted to return to his or her village, Spanish law required the soldiers to track them down and bring them back to the Mission. When they were brought back, they were beaten and confined.[28]

The priests baptized a number of Esselen during 1776, most of them children, and a few more in the following years. The priests allowed the children after baptism to continue to live with their parents in their village until they reached the "age of reason," which was about nine years old. In 1783, the soldiers fought the Excelen and killed a few of them. The battle may have resulted from the soldiers' attempts to collect the children and force them to live at the mission. Baptisms picked up again after this date, perhaps because the Excelen saw they could not defeat the soldiers and decided they wanted to be with their children. Upon baptism the Esselen were considered to be part of a monastic order and subject to the rules of that order. This placed them, by Spanish law, under the direct authority of the padres.[29]

The families lived in small rooms in generally unsanitary conditions. Over half the children born at a California mission died before age 4 and only about two of every ten lived to be teenagers.[30] The girls were separated from their families at age 8 and required to sleep in a segregated, locked dormitory called the monjero (nunnery). Once they rose, they worked inside until they finished their chores around lunch time, they were allowed some time to visit their family's homes in the mission village. Married women whose husbands were absent and widows were also required to sleep there. The boys and unmarried men also had their own dormitory, though it was less confining.[31]:117–119

Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse was a French explorer who was given a charter by the French government to survey and report on the western coast of North America. On September 14, 1786 he arrived with his two ships and visited Mission San Carlos Borromeo. Among other things, he described severe punishments inflicted on the Indians by the friars. He thought they considered the Indians "too much a child, too much a slave, too little a man."[32] Until western contact, the native people lived in small villages of between 30 and 100 people.[31] In 1786, there were 740 native men, women and children living in the village next to the Mission.[33] The priests were ignorant of the cultural differences between the tribes and forced the Rumsen and Esselen Indians to live together. The two tribes were very hostile to one another and their proximity brought ongoing strife.[29] Galaup described them as ill-fed and depressed by the strict mission routines. He said they were treated like slaves on a plantation.[33]

From 1783-1785, about 40% of the Excelen were baptized. Another three Esselen were baptized at the Soledad Mission in the early 1790s, but by 1798 the majority of the Indians had been baptized. A new priest, Father Amoró, arrived in September 1804 and injected fresh energy into baptism efforts. From 1804 to 1808, 25 individuals from Excelen were baptized during these final four years. They comprised nearly 10% of the total Excelen population who were baptized. They had held out for 33 years after proselytizing began in their area. The last five baptized were all older, from 45 to 80 years. The total number of Esselen baptized is estimated to range from 790 to 856.[34]

It may be that the older Esselen were baptized last because they were left alone after their children and grandchildren had already been coerced into living at the mission. They may have been unable to support themselves in the rugged, higher reaches of the mountains where the last remnants of the tribe hid out.[29] This is supported by recent evidence which shows that some Esselen were able to move beyond the reach of the Spanish soldiers on their horses in the rugged upper reaches of the Carmel River, Pine Valley area, Tassajara Creek, and other areas. Some may have survived into the 1840s, when they were able to filter out and find work on the nearby ranches.[5]

In 1795, the Spanish crown dictated that all religious instruction should be conducted in Spanish and that the native languages should be suppressed. This edict overturned the New Laws of 1542 which directed the missionaries to teach the natives in their own tongue. But the priests were still required to adhere to the third provincial council of Lima in 1583, which stated that the priests must give sermons and receive confession in the native people's own tongue.

Population

The Esselen were and are one of the least numerous indigenous people in California.[26] The Spanish mission system led to severe decimation of the initially small Esselen population. Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California, including the Esselen, vary substantially. Alfred L. Kroeber suggested that the 1770 population for the Esselen of 500.[35]:883[36] Sherburne F. Cook raised this estimate to 750.[35]:186 Based on baptism records and population density, Breschini calculated that they numbered 1,185-1,285.[11]

The Esselen are too often regarded as the first California Native American tribe to become culturally extinct, much to the frustration of current generations of Esselen people. By about 1822, much of the California Indian population in proximity to the missions had been forced into the Spanish mission system. Due to the proximity of the Esselen people to three of the Spanish missions, Mission San Carlos in Carmel, Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad in Soledad, and Mission San Antonio de Padua in Jolon, the tribe was heavily impacted by their presence.[11] The native population was decimated by disease, including measles, smallpox, and syphilis, which wiped out 90 percent of the native population,[37] and by conscript labor, poor food, and forced assimilation. Most of the Esselen people's villages within the current Los Padres National Forest were left largely uninhabited.[26]

The first (factor) was the food supply... The second factor was disease. ... A third factor, which strongly intensified the effect of the other two, was the social and physical disruption visited upon the Indian. He was driven from his home by the thousands, starved, beaten, raped, and murdered with impunity. He was not only given no assistance in the struggle against foreign diseases, but was prevented from adopting even the most elementary measures to secure his food, clothing, and shelter. The utter devastation caused by the white man was literally incredible, and not until the population figures are examined does the extent of the havoc become evident.[35]:200

Some anthropologists and linguists assumed that the tribe's culture had been virtually extinguished by as early as the 1840s.[11] However, existing tribe members cite evidence that some Esselen escaped the missions system entirely by retreating to the rugged interior of the Santa Lucia Mountains until the 1840s when those remaining migrated to the ranchos and outskirts of the growing towns.[29] Archaeologists located the grave of girl estimated to be about six years old buried in Isabel Meadows Cave in the Church Creek area. They calculated the date of her burial to be about 1825. Two experts received reports of Indians living in the area through the 1850s.[29] Today, contemporary generations of Esselen trace their ancestry to Esselen who were counted in early U.S. census efforts.

In 1909, forest supervisors reported that three Indian families still lived within what was then known as the Monterey National Forest. The Encinale family of 16 members and the Quintana family with three members lived in the vicinity of The Indians (now known as Santa Lucia Memorial Park west of Ft. Hunger Liggett). The Mora family consisting of three members was living to the south along the Nacimiento-Ferguson Road.[38]

Federal recognition

About 460 individuals have identified themselves as descendants of the original Esselen people and banded to together form a tribe. The Department of the Interior has set aside 45 acres (18 ha) of Fort Ord that the tribe can use to build a cultural center and museum. But they must first obtain federal recognition. They have been assisted by Alan Leventhal, a professor at San Jose State University, and Dr. Les Field of the University of New Mexico, who have helping establish the tribe's cultural identity.[39]

The tribe was briefly formally identified as a tribe by Helen Hunt Jackson, an Indian Affairs agent, in 1883. It was also identified on official Indian census rolls, maps, and in a land-rights petition sent to President Theodore Roosevelt. But in 1899, anthropologist Alfred Kroeber declared that the tribe was extinct because most tribal members had intermarried, taken Spanish names, and converted to Catholicism. Kroeber wrote in 1925:

Still farther north, from Monterey to San Francisco, and inland to Mount Diablo, were numerous squalid and interrelated bands, many of whose local village names have been preserved, but for whom there is no generic name beyond the Spanish ‘coast-men,’ Costaños, corrupted into Costanoan in technical book English. A century and a third of contact with the superior race has proved fatal to this group also, and it is as good as gone.[40]

In 1955, Kroeber decided he had made a mistake and tried to persuade the BIA, but the agency refused to listen to his arguments or accept his evidence.

In 1927, the superintendent of the Sacramento agency of the Bureau of Indian Affairs listed California tribes that should be given land rights, but he excluded the Esselen along over 135 other tribes from the list.[40] A tribal member and researcher has identified more than 100 individual Esselen who were living in Monterey County in 1923 while the group was still federally recognized. The tribe says their exclusion as a recognized tribe was a mistake that should be rectified.[39]

Many anthropologists believed that the Costanoan-speaking people encompassed a geographical area from north of San Francisco to Monterey. The name Costanoan is derived from a generic name Costaños (‘coast-men) applied by the Spanish to all native people on the coast. It was later corrupted as Costanoan in the English language. As a result of the 1928 California Indian Jurisdictional Act enrollment, almost every Bureau of Indian Affairs “enrollee” of Esselen descent was categorized as Costanoan by the agency.[40]

In 2010 the Esselen Nation petitioned the federal government for recognition as a tribe.[41] The Bureau of Indian Affairs says the tribe does not meet the formal criteria used to recognize a tribe.[42]

In popular culture

The Esalen Institute in Big Sur is named after this tribe as was the former Boy Scouts of America Monterey Bay Area Council Order of the Arrow Esselen Lodge #531.[43]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Breschini, Gary S.; Haversat, Trudy. "An Overview of the Esselen Indians of Monterey County". Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ↑ Levy, p.486

- ↑ Bean, p.xxi

- 1 2 "The Esselen Indians". Esalen Institute. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- 1 2 Breschini, Gary S.; Haversat, Trudy. "Linguistics and Prehistory: A Case Study from the Monterey Bay Area".

- ↑ Friedburg, Peter. "The Esselen Hands". Esalen Institute.

- ↑ Hester, pp.498-499

- ↑ Kroeber, Alfred L. (1925). Handbook of the Indians of California.

- ↑ Mithun, Marianne (July 2001). The Languages of Native North America. Santa Barbara: University of California. ISBN 0521232287. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ↑ "Nation's Name". Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Breschini, Gary S.; Trudy Haversat. "A Brief Overview of the Esselen Indians of Monterey County". Montery County Historical Society. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Santa Lucia Range ecological subregion information". Archived from the original on March 15, 2005. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ↑ Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- 1 2 3 Meighan, Clement W. (1952). "Excavation of Isabella Meadows Cave, Monterey County California" (PDF). Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- 1 2 Henson, Paul; Donald J. Usner (1993). "The Natural History of Big Sur" (PDF). University Of California Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ↑ Priestly, H. I. (1937). A Historical, Political and Natural Description of California by Pedro Fages. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- 1 2 3 Watkins, Rolin G. (1925). History of Monterey and Santa Cruz Counties, California (PDF). Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co. pp. 41–42. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ↑ Tule rush houses, redwood houses and sweat lodges, Teixeira, 1997:2

- ↑ Redwood houses in Monterey, Kroeber, 1925:468

- ↑ Tule boats, Kroeber, 1925:468

- ↑ Elliot, Analise (January 2005). Hiking & Backpacking Big Sur: A Complete Guide to the Trails of Big Sur. Wilderness Press. p. 323. ISBN 0-89997-326-4.

- ↑ Smith, Frances Rand (1921). The Architectural History of Mission San Carlos Borromeo, California. Berkeley, California: California Historical Survey Commission. p. 18.

The mission was established in the new location on August 1, 1771; the first mass was celebrated on August 24, and Serra officially took up residence in the newly constructed buildings on December 24.

- 1 2 Walton, John (2003). Storied Land: Community and Memory in Monterey. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. p. 15ff. ISBN 9780520935679. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 253.

- ↑ Paddison, Joshua (ed.) (1999). A World Transformed: Firsthand Accounts of California Before the Gold Rush. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books. p. 23. ISBN 1-890771-13-9. (Fages regarded the Spanish installations in California as military institutions first and religious outposts second.)

- 1 2 3 Blakley, E.R. "Jim"; Barnette, Karen (July 1985). "Historical Overview of the Los Padres National Forest" (PDF). ForestWatch.

- ↑ Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- 1 2 "Costanoan Rumsen Carmel Tribe". Costanoan Rumsen. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Breschini, Gary S.; Haversat, Trudy. "Post-Contact Esselen Occupation of the Santa Lucia Mountains". Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ↑ "What was life like for the Indian children living at the mission?". California Missions Resource Center. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- 1 2 Fogel, Daniel (1988). Junípero Serra, the Vatican and Enslavement Theology. San Francisco: Ism Press. ISBN 978-0910383257.

- ↑ Castillo, Elias (November 8, 2004). "The dark, terrible secret of California's missions". Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- 1 2 "Jean Francois Galaup, Comte De La Perouse". Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- ↑ Breschini, Gary S.; Haversat, Trudy. "A Brief Overview of the Esselen Indians of Monterey County". Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Cook, Sherburne F. (1976). The Population of the California Indians, 1769-1970. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Kroeber, A. L. (1925). "Handbook of the Indians of California" (78). Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin: 883.

- ↑ Kripal, J. Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion. University of Chicago Press. (2007) p. 31

- ↑ Blakely, Jim; Barnette, Karen (July 1985). Historical Overview: Los Padres National Forest (PDF).

- 1 2 Moore, Sylvia (April 20, 2003). "Esselen Nation fights for identity". Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 Escobar, Lorraine; Field, Les; Leventha, Alan (September, 1999). "Understanding the Composition of Costanoan/Ohlone People". Retrieved October 12, 2016. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Tribe Petitions For Federal Recognition". Central Coast, California: KSBW Action News 8. April 29, 2003.

- ↑ "Ohlone/Costonoan Nation" (PDF). September 24, 2013.

- ↑ Doane, Jeff. "Legend of White Bear". Salinas, California. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

References

- Bean, Lowell John, editor. 1994. The Ohlone: Past and Present Native Americans of the San Francisco Bay Region. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press Publication. ISBN 0-87919-129-5. Includes Leventhal et al. Ohlone Back from Extinction.

- Breschini, Gary S. and Trudy Haversat 2004. The Esselen Indians of the Big Sur Country: The Land and the People. Salinas, CA: Coyote Press.

- Breschini, Gary S. and Trudy Haversat 2005. A Brief Overview of the Esselen Indians of Monterey County. File retrieved Sep 7, 2007.

- Levy, Richard. 1978. Costanoan, in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 8 (California). William C. Sturtevant, and Robert F. Heizer, eds. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978. ISBN 0-16-004578-9 / 0160045754

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1976. The Conflict between the California Indian and White Civilization. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, D.C.

- Hester, Thomas R. 1978. Esselen, in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 8 (California). William C. Sturtevant, and Robert F. Heizer, eds. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978, pages 496-499. ISBN 0-16-004578-9 / 0160045754

External links

- Esselen Tribal Website

- Ohlone Costanoan Tribal Website

- An Overview of the Esselen Indians of Monterey County - Big Sur Chamber of Commerce