Electromagnetic articulography

Electromagnetic articulography (EMA) is a method of measuring the position of parts of the mouth. EMA uses sensor coils placed on the tongue and other parts of the mouth to measure their position and movement over time during speech and swallowing. Induction coils around the head produce an electromagnetic field that creates, or induces, a current in the sensors in the mouth. Because the current induced is inversely proportional to the cube of the distance, a computer is able to analyse the current produced and determine the sensor coil's location in space.

EMA is used in linguistics and speech pathology to study articulation and in medicine to study oropharyngeal dysphagia. Unlike other methods of data collection, EMA does not expose subjects to ionizing radiation and allows for large amounts of data to be collected easily.

Principles of operation

The ability to observe the movements of articulators has been of great importance to the study of phonetics in order to understand the way sounds are produced.[1]

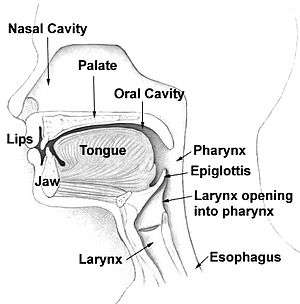

Electromagnetic articulography uses the principle of electromagnetic induction to measure the position and movement of various points in and around the mouth. A helmet containing electromagnetic transmitters creates a variable magnetic field by running currents through the transmitters at different frequencies. Sensor coils placed midsagittally in the mouth produce current as they move through the magnetic field inversely proportional to the cube of the distance from the transmitters.[2] The current induced alternates at the same frequency as the transmitter coil and the composite signal can be separated out to determine the distance from each individual coil, thus determining the position of the sensor in space.[3][4]

In two-dimensional articulography, transmitter coils are placed in an equilateral triangle along the midsagittal plane at the forehead, chin, and neck.[2] Because of the geometric orientation of the transmitter coils, accurate readings are able to be taken as long as the sensor coils placed on the tongue stay within about a centimeter of the midsagittal plane and are not angled at more than 30 degrees.[4]

Articulographs able to measure in three dimensions use six transmitter coils organized in a spherical configuration. The transmitters are arranged so that the axis of a sensor coil is never perpendicular to more than three transmitters. Through the transmitter configuration and ability to measure in multiple dimensions, three-dimensional articulographs are able to make measurements outside of the midsagittal plane. 2D articulographs require restrictive headmounts to ensure that the subject's head does not move off the plane of measurement. Because 3D articulographs are able to measure outside of the midsagittal plane, a less restrictive headmount is able to be used.[5]

Development of two and three dimensional sensors

Thomas Hixon was the first to describe the use of electromagnetic principles to measure articulation. In his letter to the editor, published in The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, he described a setup using two sensor coils and one generator coil. The sensor coils, attached to the forehead and back of the neck, would remain stationary while the generator coil, attached to the jaw, would move creating variable currents in the sensor coils. These currents could then be used to determine the distance in two dimensions.[6]

Early EMA systems like Hixon's had problems with accounting for tilting of the tongue during use as tilting of the sensor coils causes changes in the induced current that can skew data.[1] In 1987, Paul Schönle et al. published an improved system that used three transmitter coils (analogous to Hixon's generator coil) and computer software to triangulate the position of sensor coils and account for tilt.[1] However modern two-dimensional systems are still unable to compensate for tilting of sensors past 30 degrees and measurement is distorted if sensor coils are moved off the centerline of the mouth.[2][4] In 1993, Andreas Zierdt published a description of an articulograph that would be able to measure movement in three dimensions, though three dimensional articulographs have only been commercially available since around 2009.[5] Zierdt's conceptualization placed six transmitter coils equidistant from each other. Because sensor coils are dipoles, when they are perpendicular to a transmitter coil the current induced is zero, so Zierdt angled the transmitter coils so that for any given rotation of a sensor coil, it was not perpendicular to more than three transmitter coils allowing for at least three transmitter coils to triangulate the position of the sensor.[5][7]

Effect on subjects

As sensor coils are placed on the tongue of the subject, articulation may be affected depending on the placement of the coils, but no comparative analysis has shown whether articulation is altered because of the coils. The coils are about 3mm in size and are not considered to be a particularly large source of error for measurements. Some researchers have found that subjects are irritated by sensor coils placed on the tip of the tongue which can lead to disturbed articulation. Similarly, the wires attached to the sensor coils can inhibit articulation if not run out the side of the mouth.[8]

It has not been shown that long term exposure to electromagnetic fields is harmful to human health, but it is recommended to avoid subjects who are pregnant or who utilize pacemakers. Guidelines place the limit for safe continuous exposure between 100μT and 200μT.[9] The field and frequencies output by electromagnetic articulographs are comparable to those put out by computer terminals with the maximum measured being about 10μT.

Alternative methods

Various diagnostic techniques preceded electromagnetic articulography.

Palatography and electropalatography

Palatography and electropalatography both measure contact of the tongue with the palate and thus are unable to measure articulations that do not make contact with the palate such as vowels.[10]

Palatography involves the painting of a colored substance onto the tongue which is then transferred onto the palate during articulation. A picture is then taken of the palate to record the location of contact and, if another palatogram is to be taken, the mouth is washed out and the tongue repainted. A particularly low cost method that is often used in fieldwork, it can be difficult to collect large amounts of data.[10][11]

Electropalatography involves the use of a custom-fitted artificial palate containing electrodes that measure contact. While able to record multiple contacts, the artificial palate may obstruct or interfere with articulation, and each subject requires a custom-fitted palate.[12]

Video fluoroscopy

Video fluoroscopy uses x-ray radiation to produce moving pictures of the mouth during articulation or swallowing. It is considered the gold standard in studies of dysphagia because of its ability to take videos of the entire digestive tract during swallowing events.[13] It is often used to study and treat aspiration of food, what parts of the digestive tract are malfunctioning during swallowing, and positions in which swallowing is easiest.[14] Only limited data is able to be collected as sessions are typically limited to three minutes due to the hazards of radiation exposure.[4][15] and it does not allow for fine grain analysis of tongue movements.

X-ray microbeam

Similar to video fluoroscopy, X-ray microbeam studies use radiation to study movements of articulators. Gold pellets, 2 to 3 mm in size, are placed in and around the mouth similar to the coils used in EMA. Radiation exposure is limited by using computer software to focus narrow x-ray beams, about 6mm2, on the pellets and track them as they move.[16] Like EMA, x-ray microbeam studies are limited by the placement of the pellets. While able to minimize radiation exposure, the system is largely inaccessible as it is unique to the University of Wisconsin.[4][16][17]

References

- 1 2 3 Schönle, Paul; Klause Gräbe; Peter Wenig; Jörg Höhne; Jörg Schrader, and Bastian Conrad. 1987. Electromagnetic Articulography: Use of Alternating Magnetic Fields for Tracking Movements of Multiple Points Inside and Outside the Vocal Tract. Brain and Language 31. 26–35.

- 1 2 3 Zhang, Jie; Ian Maddieson; Taehong Cho, and Marco Baroni. 1999. Articulograph AG100 Electromagnetic Articulation Analyzer Homemade Manual UCLA Phonetics Lab. Web: UCLA. Accessed 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Maassen, Ben, and Pascal van Lieshout. 2010. Speech Motor Control: New Developments in Basic and Applied Research, 325. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed 16 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Steele, Catriona. 2004. Use of Electromagnetic Midsagittal Articulography in the Study of Swallowing. Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research 47. 342–352.

- 1 2 3 Yunusova, Yana; Jordan Green, and Antje Mefferd. 2009. Accuracy Assessment for AG500, Electromagnetic Articulograph. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 52. 547–555.

- ↑ Hixon, Thomas. 1971. An Electromagnetic Method for Transducing Jaw Movements during Speech. Acoustical Society of America 49. 603–606.

- ↑ Zierdt, Andreas. 1993. Problems of Electromagnetic Position Transduction for a Three-Dimensional Articulographic Measurement System. Institut fur Phonetik und sprachliche Kommunikation der Universitat Munchen - Forschungsberichte 31. 137–141.

- ↑ Hardcastle, William, and Nigel Hewlett. 2006. Coarticulation: Theory, Data, and Techniques. (Cambridge Studies in Speech Science and Communication). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Bernhardt, J.H.. 1988. The establishment of frequency dependent limits for electric and magnetic fields and evaluation of indirect effects. Radiation and Environmental Biophysics 27. 1–27.

- 1 2 Anderson, Victoria; Patrick Barjam; Robert Bowen, and Katya Pertsova. 2003. Practical Points. (Static Palatography). Web: University of California Los Angeles Linguistics. Accessed 7 July 2015.

- ↑ Anderson, Victoria; Patrick Barjam; Robert Bowen, and Katya Pertsova. 2003. Palatograms. (Static Palatography). Web: University of California Los Angeles Linguistics. Accessed 7 July 2015.

- ↑ Toutios, Asterios, and Konstantinos Margaritis. 2005. On the acoustic-to-electropalatographic mapping. Nonlinear Analyses and Algorithms for Speech Processing ed. by Marcos Faundez-Zanuy, Léonard Janer, Anna Esposito, Antonio Satue-Villar, Josep Roure, and Virginia Espinosa-Duro, 186–195. Barcelona,Spain: International Conference on Non-Linear Speech Processing.

- ↑ Olthoff, Arno; Shuo Zhang; Renate Schweizer, and Jens Frahm. 2014. On the Physiology of Normal Swallowing as Revealed by Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Real Time. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2014. n.p..

- ↑ American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. n.d.. Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study (VFSS). Web: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Accessed 24 July 2015.

- ↑ Gramigna, Gary. 2006. How to perform video-fluoroscopic swallowing studies.GI Motility online ed. by Raj Goyal, and Reza Shaker, n.p.. Part 1; (GI Motility online). Web: Nature. Accessed 7 July 2015.

- 1 2 Westbury, John. 1991. The significance and measurement of head position during speech production experiments using the x-ray microbeam system. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 89. 1782 – 1793. Accessed 24 July 2015.

- ↑ Westbury, John. June 1994. XRMB History. X-ray Microbeam Speech Production Database User's Handbook, 4–7. University of Wisconsin.

External links

- The Electromagnetic Articulograph (EMA) at the Centre for Research on Brain, Language, and Music on YouTube