Edestus

| Edestus Temporal range: Late Carboniferous | |

|---|---|

| |

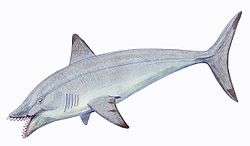

| Life restoration of Edestus protopirata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Holocephali |

| Order: | †Eugeneodontida |

| Family: | Edestidae |

| Genus: | Edestus |

| Species | |

|

see text. | |

Edestus is a genus of eugeneodontid holocephalid that lived throughout the world's oceans during the late Carboniferous. All of the species are known only from their teeth. The term "edestid" is often used to refer to any or all members of the order Eugeneodontiformes, though, strictly speaking, "edestid" properly refers only to members of the family Edestidae. Edestus is a Greek name derived from the word edeste (to devour), in reference to the aberrant quality and size of the species' teeth.[1] The largest species, E. giganteus, could reach 6 m (20 ft) in length, the size of a modern great white shark.[2]

Like its other relatives, such as Helicoprion, and unlike modern sharks, the species of Edestus grew teeth in curved brackets, and did not shed the teeth as they became worn. In Edestus' case, there was only a single row of teeth in each jaw, so that the mouth would have resembled a monstrous pair of pinking shears. The degree of curvature in the teeth brackets, along with size are distinct in each species.

Because the teeth are sharp and serrated, all of the species are presumed to have been carnivorous. Exactly how they captured, or even ate, their prey, along with their appearance, remains pure speculation until a more complete fossil, or skull, is found. One such theory as to how Edestus might have hunted and killed its prey was found by Wayne M. Itano of the Natural History Museum of the University of Colorado et al. Itano examined specimens of Edestus minor from the Late Carboniferous deposits of Texas and discovered wear patterns that suggest that Edestus might have hunted by using its bizarre array of teeth to vertically thrash its prey, creating slashing wounds, thus incapacitating and then swallowing its prey. Such a method of predation would prove unique and as-yet-unknown elsewhere in the animal kingdom if correct. Examination of the wear marks of the specimens in Itano's study also suggest that Edestus might have preyed on tough-skinned animals, though what kind remains unknown.[3][4]

Species

- Edestus giganteus, (also known as the "scissor-tooth shark") lived in the oceans during the Late Carboniferous (306-299 million years ago).

Little is known about E. giganteus apart from a single set of teeth currently housed in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Paleontological studies suggest that E. giganteus, unlike modern-day sharks, did not shed worn or broken teeth. Rather, it continued growing new teeth and gums near the back of the mouth, eventually pushing the older teeth and gums forward, until they protruded from the mouth. It is not clear what function the strange teeth performed.

E. giganteus is estimated to have grown to about the size of the modern-day great white shark, thus probably making it one of the top sea predators of its day. As with all other members of the genus, it is not clear how E. giganteus could catch, or eat its prey, though research of Edestus minor published in 2015 by Wayne M. Itano suggests that E. giganteus might have hunted and killed its prey by vertical thrashing attacks to slash and cripple prey.[5]

- E. heinrichi

- E. mirus

- E. minor

- E. vorax

References

- ↑ ISBN 9781258302863 A Source-book of Biological Names and Terms, Edward Jaeger (1944)

- ↑ "Helicoprion: an Intriguing Puzzle". Elasmo-research.org. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- ↑ http://www.academia.edu/12187750/An_abraded_tooth_of_Edestus_Chondrichthyes_Eugeneodontiformes_Evidence_for_a_unique_mode_of_predation

- ↑ http://www.eartharchives.org/articles/weird-fossil-of-the-week-edestus/

- ↑ http://www.academia.edu/12187750/An_abraded_tooth_of_Edestus_Chondrichthyes_Eugeneodontiformes_Evidence_for_a_unique_mode_of_predation