Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (play)

| Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde | |

|---|---|

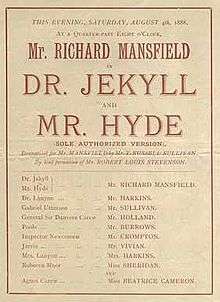

Playbill for London production in 1888 | |

| Written by | Thomas Russell Sullivan |

| Characters | Henry Jekyll/Edward Hyde |

| Date premiered | May 9, 1887 |

| Place premiered | Boston Museum |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | |

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is a play written by Thomas Russell Sullivan in collaboration with actor Richard Mansfield, who starred in its initial productions. It is an adaptation of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, an 1886 novella written by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson.

History

Mansfield read Stevenson's novella and was immediately attracted to the idea of adapting it for the stage. Although copyright law in the United States allowed for free adaptation of works first published in England, Mansfield secured permission for both the American and British stage rights. He turned to Sullivan, a friend of his from Boston who was a writer, to create the script.

It premiered at the Boston Museum on May 9, 1887, making it the first American adaptation of Stevenson's story.[1] After a few days it was withdrawn for rewrites. The updated version debuted at the Madison Square Theatre on Broadway on September 12, 1887, with A. M. Palmer producing.

Sullivan and Mansfield took the play to England, where it opened at the Lyceum Theatre in London's West End on August 4, 1888. Mansfield's performance as a man transformed into a maniac was praised by critics, but it had unexpected consequences when the Jack the Ripper murders began during the play's London run. Mansfield was mentioned in the press as a possible suspect in the killings. He attempted to defuse any public concern by staging a charity performance of the comedy Prince Karl.[2]

Mansfield continued to perform the play's title role in various productions until a few months before his death in August 1907.

Cast and characters

The casts for the performances at the Boston Museum, Broadway's Madison Square Theatre, and the West End's Lyceum were as follows:[3]

| Character | Boston cast | Broadway cast | West End cast |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde | Richard Mansfield | Richard Mansfield | Richard Mansfield |

| General Sir Danvers Carew | Boyd Putnam | H.B. Bradley | Mr. Holland |

| Dr. Lanyon | Alfred Hudson | Daniel H. Harkins | Daniel H. Harkins |

| Gabriel Utterson | Frazier Coulter | John T. Sullivan | John T. Sullivan |

| Poole | James Burrows | Harry Gwynette | J. C. Burrows |

| Inspector Newcome | Arthur Falkland | C. E. Eldridge | W. H. Compton |

| Jarvis | J. K. Applebee, Jr. | Thomas Goodwin | F. Vivian |

| Mrs. Lanyon | Kate Ryan | Katherine Rogers | Mrs. Daniel H. Harkins |

| Agnes Carew | Isabelle Evesson | Beatrice Cameron | Beatrice Cameron |

| Rebecca Moore | Emma V. Sheridan | Helen Glidden | Emma V. Sheridan |

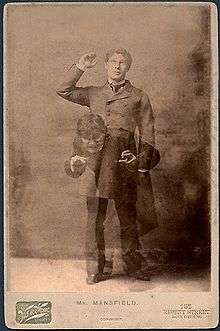

Dramatic analysis

Mansfield's transformation between the Jekyll and Hyde personae included the use of lighting changes and makeup designed to appear different under colored filters, but it was mostly accomplished by the actor's facial contortions and changes in posture and movement. The effect was so dramatic, however, that audiences and journalists speculated extensively about how it was achieved. The theories included claims that he had an inflatable rubber prosthetic; that he applied various chemicals; and that he had a mask hidden in a wig, which he pulled down to complete the change.[4][5][6][7]

In contrast to the original story where the physical transformation of Jekyll and Hyde is revealed near the end, most dramatic adaptations show it early in the narrative, because it is expected by viewers who are familiar with the idea. As one of the first adapters, Sullivan was working in an environment where the transformation could still shock the audience, and he held back the reveal until the third act. Sullivan's adaptation also strengthened the contrast between the two personae. Hyde was made more explicitly evil, while Jekyll was represented as more conventional, than either was in Stevenson's original, although Mansfield resisted making the characterizations too simplistic.[8]

Reception

Reviewing the initial production at the Boston Museum, The Boston Post "warmly congratulated" Sullivan for his script, saying it overcame the difficulties of turning Stevenson's story into a drama, with only a few flaws. Mansfield's performance was praised for drawing a clear distinction between Jekyll and Hyde, although the reviewer found his portrayal of Hyde better crafted than his Jekyll. The audience was reported to have reacted very favorably, with long applause and several curtain calls for Mansfield.[9] The Cambridge Tribune said the audience reaction affirmed "that the play and its production were a work of genius".[10]

References

- ↑ Rose, Brian A. (1996). Jekyll and Hyde Adapted: Dramatizations of Cultural Anxiety. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 51.

- ↑ Holgate, Mike (2013). "Richard Mansfield (1857-1907)". Jack the Ripper: The Celebrity Suspects. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-5383-2.

- ↑ Winter, William (1910). The Life and Art of Richard Mansfield. 2. New York: Moffat, Yard and Company. pp. 262–264. OCLC 1513656.

- ↑ Danahay, Martin A. & Chisholm, Alexander, eds. (2011) [2004]. Jekyll and Hyde Dramatized: The 1887 Richard Mansfield Script and the Evolution of the Story on Stage (Kindle ed.). McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-1870-1.

- ↑ Rose, Brian A. (1996). Jekyll and Hyde Adapted: Dramatizations of Cultural Anxiety. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 49.

- ↑ "Mr. Mansfield's Art". The New York Times. 27 (11,331). December 25, 1887. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Stage: Gossip about Plays and Actors". The New York Daily Tribune. 47 (15,015). December 25, 1887. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Rose, Brian A. (1996). Jekyll and Hyde Adapted: Dramatizations of Cultural Anxiety. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 51–52, 54–56.

- ↑ "The Theatres: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde". The Boston Post. 112 (111). May 10, 1887. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Dust". The Cambridge Tribune. 10 (10). May 14, 1887. p. 2.