History of penicillin

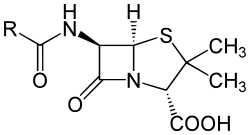

Penicillin core structure, where "R" is the variable group.

Alexander Fleming was the first to suggest the Penicillium mould must secrete an antibacterial substance, and the first to concentrate the active substance which he named penicillin in 1928, and during the next twelve years he grew and distributed the original mould, but he was not the first to use its properties in medicine. Others involved in the mass production of penicillin include Ernst Chain, Howard Florey and Norman Heatley.

| Year | Location | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient times | Egypt, Greece & India | Many ancient cultures, including the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and in ancient India, already used moulds and other plants to treat infection.[1] This worked because some moulds produce antibiotic substances. However, they could not identify or isolate the active component in the moulds. |

| "traditional" | Russia | Russian peasants used warm soil as treatment for infected wounds.[2] |

| c. 150 BC | Sri Lanka | Soldiers in the army of king Dutugemunu (161–137 BC) are recorded to have stored oil cakes (a traditional Sri Lankan sweetmeat) for long periods in their hearth lofts before embarking on their campaigns, in order to make a poultice of the cakes to treat wounds. It is assumed that the oil cakes served the dual functions of desiccant and antibacterial. |

| 1600s | Poland | Wet bread was mixed with spider webs (containing spores) to treat wounds. The technique was mentioned by Henryk Sienkiewicz in his 1884 book With Fire and Sword. |

| 1640 | England | The idea of using mould as a form of treatment was recorded by apothecaries, such as John Parkington, King's Herbarian, who advocated the use of mould in his book on pharmacology. |

| 1870 | United Kingdom | Sir John Scott Burdon-Sanderson, who started out at St. Mary's Hospital 1852–1858 and as lecturer there 1854–1862 observed that culture fluid covered with mould would produce no bacteria. |

| 1871 | United Kingdom | Burdon-Sanderson's discovery prompted Joseph Lister, an English surgeon and the father of modern antisepsis to investigate that urine samples contaminated with mould did not allow the growth of bacteria. He also described the antibacterial action on human tissue of what he called Penicillium glaucum.[3] A nurse at King's College Hospital whose wounds did not respond to any antiseptic, was then given another substance that cured her, and Lister's registrar informed her that it was called Penicillium. |

| 1874 | United Kingdom | William Roberts observed that bacterial contamination is generally absent in cultures of the mould Penicillium glaucum. |

| 1875 | United Kingdom | John Tyndall followed up on Burdon-Sanderson's work and demonstrated to the Royal Society the antibacterial action of the Penicillium fungus.[4] |

| 1875 | Bacillus anthracis was shown to cause anthrax. This was the first demonstration that a specific bacterium caused a specific disease. | |

| 1877 | France | Louis Pasteur and Jules Francois Joubert observed that cultures of the anthrax bacilli, when contaminated with moulds, became inhibited. Some references say that Pasteur identified the strain as Penicillium notatum. |

| 1887 | France | Garré found similar results. |

| 1895 | Italy | Vincenzo Tiberio, physician of the University of Naples published a research about a mould in a water well in Arzano, Italy that had an antibacterial action.[5][6][7][8] |

| 1897 | France | Ernest Duchesne at École du Service de Santé Militaire in Lyon independently discovered healing properties of a Penicillium glaucum mould, even curing infected guinea pigs from typhoid. He published a dissertation[9][10][11] in 1897 but this was ignored by the Institut Pasteur. However Duchesne was himself using a discovery made by Arab stable boys, who were using moulds to cure sores on horses. He did not claim that the mould contained any antibacterial substance, only that the mould somehow protected the animals.

|

| 1920 | Belgium | Andre Gratia and Sara Dath observed a fungal contamination in one of their Staphylococcus aureus cultures that was inhibiting the growth of the bacterium. They identified this as a species of Penicillium and presented their observations as a paper. There was little attention to this paper. |

| 1923 | Costa Rica | An Institut Pasteur scientist, Costa Rican Clodomiro Picado Twight recorded the antibiotic effect of Penicillium. |

| 1928 | United Kingdom | Scottish biologist Sir Alexander Fleming noticed a halo of inhibition of bacterial growth around a contaminant blue-green mould on a Staphylococcus plate culture. He concluded that the mould was releasing a substance that was inhibiting bacterial growth. He grew a pure culture of the mould and discovered that it was Penicillium notatum. With help from a chemist, he concentrated what he later named "penicillin". During the next twelve years, he grew and distributed the original mould, unsuccessfully trying to get help from any chemist that had enough skill to make a stable form of it, for mass production. |

| 1930 | United Kingdom | Cecil George Paine, a pathologist at the Royal Infirmary in Sheffield, attempted to treat sycosis (eruptions in beard follicles) with penicillin but was unsuccessful, probably because the drug did not penetrate deep enough. Moving on to ophthalmia neonatorum, a gonococcal infection in babies, he achieved the first cure on 25 November 1930. He cured four patients (one adult, the others babies) of eye infections, although a fifth patient was not so lucky.[12] |

| 1938 | United Kingdom | In Oxford, Howard Walter Florey organized his large and very skilled biochemical research team, notable among them Ernst Boris Chain and Norman Heatley, to undertake innovative work to produce a stable penicillin. |

| 1941–1943 | USA | Peoria, Illinois: Moyer, Coghill and Raper at the USDA Northern Regional Research Laboratory (NRRL) developed methods for industrialized penicillin production and isolated higher-yielding strains of the Penicillium fungus.[13][14] |

| 1941–1944 | USA | Brooklyn, New York: Jasper H. Kane and other Pfizer scientists developed the practical, deep-tank fermentation method for production of large quantities of pharmaceutical-grade penicillin.[15] |

| 1945 | United Kingdom | Oxford: Using X-ray crystallographic analysis, Dorothy Hodgkin elucidated the correct chemical structure of penicillin.[16] |

| 1952 | Austria | Kundl, Tyrol: Hans Margreiter and Ernst Brandl of Biochemie (now Sandoz) developed the first acid-stable penicillin for oral administration, Penicillin V.[17] |

| 1957 | USA | Chemist John C. Sheehan at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) completed the first chemical synthesis of penicillin in 1957.[18] |

References

- ↑ "History of Antibiotics | Steps of the Scientific Method, Research and Experiments". Experiment-Resources.com. Retrieved 2012-07-13

- ↑ Гоголь Николай Васильевич. "Тарас Бульбаa". http://lib.ru/. Retrieved 2014-02-13. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ MacFarlane, Gwyn (1979). Howard Florey : the making of a great scientist. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Pr. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0198581610.

- ↑ Douglas Allchin. "Penicillin & Chance". SHiPS Resource Center. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ↑ Tiberio, Vincenzo (1895) "Sugli estratti di alcune muffe" [On the extracts of certain molds], Annali d'Igiene Sperimentale (Annals of Experimental Hygiene), 2nd series, 5 : 91–103. From p. 95: "Risulta chiaro da queste osservazioni che nella sostanza cellulare delle muffe esaminate son contenuti dei principi solubili in acqua, forniti di azione battericida: sotto questo riguardo sono più attivi o in maggior copia quelli dell' Asp. flavescens, meno quelli del Mu. mucedo e del Penn. glaucum." (It follows clearly from these observations that in the cellular substance of the molds examined are contained some water-soluble substances, provided with bactericidal action: in this respect are more active or in greater abundance those of Aspergillus flavescens; less, those of Mucor mucedo and Penicillium glaucum.)

- ↑ Bucci R., Galli P. (2011) "Vincenzo Tiberio: a misunderstood researcher," Italian Journal of Public Health, 8 (4) : 404–406. (Accessed 1 May 2015)

- ↑ "Almanacco della Scienza CNR". Almanacco.rm.cnr.it. 2011-03-02. Retrieved 2012-07-13

- ↑ Salvatore De Rosa, Introduttore: Fabio Pagan. "Vincenzo Tiberio, vero scopritore degli antibiotici - Festival della Scienza" (in Italian). Festival2011.festivalscienza.it. Retrieved 2012-07-13

- ↑ Duchesne 1897, Antagonism between molds and bacteria. An English translation by Michael Witty. Fort Myers, 2013. ASIN B00E0KRZ0E and B00DZVXPIK.

- ↑ Ernest Duchesne, Contribution à l'étude de la concurrence vitale chez les micro-organismes : antagonisme entre les moisissures et les microbes [Contribution to the study of the vital competition in microorganisms: antagonism between molds and microbes], (Lyon, France: Alexandre Rey, 1897).

- ↑ Une découverte oubliée : la thèse de médecine du docteur Ernest Duchesne (1874–1912)

- ↑ Wainwright M, Swan HT (January 1986). "C.G. Paine and the earliest surviving clinical records of penicillin therapy". Med Hist. 30 (1): 42–56. doi:10.1017/S0025727300045026. PMC 1139580

. PMID 3511336.

. PMID 3511336. - ↑ "Penicillium chrysogenum (aka P. notatum), the natural source for the wonder drug penicillin, the first antibiotic". Tom Volk's Fungus of the Month for November 2003.

- ↑ "Historic Peoria, Illinois". Northern Regional Research Lab.

- ↑ "1900–1950". Exploring Our History. Pfizer Inc. 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ↑ Curtis, Rachel; Jones, John (2007). "Robert Robinson and penicillin: an unnoticed document in the saga of its structure". Journal of Peptide Science. 13: 769–775. doi:10.1002/psc.888.

- ↑ "Serie Forschung und Industrie: Sandoz". Medical Tribune (in German). Vienna: Medizin Medien Austria GmbH (45/2005). Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ↑ E. J. Corey; John D. Roberts. "Biographical Memoirs: John Clark Sheehan". The National Academy Press. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

Further reading

- Bud, Robert (2007). Penicillin: Triumph and Tragedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199254064.

External links

- History of Antibiotics, archived from the original on 14 May 2002, retrieved 6 August 2013—from a course offered at Princeton University.

- Brown, Kevin W. (St Mary's Trust Archivist and Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum Curator) (2004). Penicillin man: Alexander Fleming and the antibiotic revolution. Scarborough, Ont: Sutton Pub. ISBN 0-7509-3152-3.

(Most of the information in this article comes from this book) - Debate in the House of Commons on the history and the future of the discovery

This article is issued from Wikipedia - version of the 11/28/2016. The text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share Alike but additional terms may apply for the media files.