Dentin hypersensitivity

| Dentin Hypersensitivity | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | K03.8 |

| MeSH | D003807 |

Dentin hypersensitivity (abbreviated to DH,[1] or DHS,[2] and also termed sensitive dentin,[3] dentin sensitivity,[4] cervical sensitivity,[5] and cervical hypersensitivity[5]) is dental pain which is sharp in character and of short duration, arising from exposed dentin surfaces in response to stimuli, typically thermal, evaporative, tactile, osmotic, chemical or electrical; and which cannot be ascribed to any other dental disease.[2][5][6][7]

A degree of dentin sensitivity is normal, but pain is not usually experienced in everyday activities like drinking a cooled drink. Therefore, although the terms dentin sensitivity and sensitive dentin are used interchangeably to refer to dental hypersensitivity,[5] the latter term is the most accurate.

Symptoms

The pain is sharp and sudden, in response to an external stimulus.[7] The most common trigger is cold,[1] with 75% of people with hypersensitivity reporting pain upon application of a cold stimulus.[5] Other types of stimuli may also trigger pain in dentin hypersensitivity, including:

- Thermal – hot and cold drinks and foods,[7] cold air, coolant water jet from a dental instrument.

- Electrical – electric pulp testers.[8]

- Mechanical–tactile – dental probe during dental examination,[8] periodontal scaling and root planing,[8] toothbrushing.[7]

- Osmotic – hypertonic solutions such as sugars.[8]

- Evaporation – air blast from a dental instrument.[8]

- Chemical – acids,[8] e.g. dietary, gastric, acid etch during dental treatments.

The frequency and severity with which the pain occurs are variable.[2]

Causes

The main cause of DH is gingival recession (receding gums) with exposure of root surfaces, loss of the cementum layer and smear layer, and tooth wear.[8] Receding gums can be a sign of long-term trauma from excessive or forceful toothbrushing, or brushing with an abrasive toothpaste (dental abrasion),[8][9] or a sign of chronic periodontitis (gum disease).[9] Other less common causes are acid erosion (e.g. related to gastroesophageal reflux disease, bulimia or excessive consumption of acidic foods and drinks), and periodontal root planing.[9] Dental bleaching is another known cause of hypersensitivity.[8] Other causes include smoking tobacco, which can wear down enamel and gum tissue, cracked teeth or grinding of teeth (bruxism).[10]

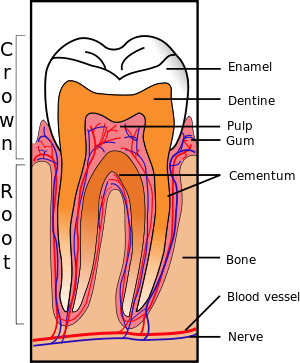

Dentine contains many thousands of microscopic tubular structures that radiate outwards from the pulp; these dentinal tubules are typically 0.5–2 micrometres in diameter. Changes in the flow of the plasma-like biological fluid present in the dentinal tubules can trigger mechanoreceptors present on nerves located at the pulpal aspect, thereby eliciting a pain response. This hydrodynamic flow can be increased by cold, air pressure, drying, sugar, sour (dehydrating chemicals), or forces acting onto the tooth. Hot or cold food or drinks, and physical pressure are typical triggers in those individuals with teeth sensitivity.

Most experts on this topic state that the pain of DH is in reality a normal, physiologic response of the nerves in a healthy, non-inflamed dental pulp in the situation where the insulating layers of gingiva and cementum have been lost;[2][5] i.e., dentin hypersensitivity is not a true form of allodynia or hyperalgesia. To contradict this view, not all exposed dentin surfaces cause DH.[5] Others suggest that due to the presence of patent dentinal tubules in areas of hypersensitive dentin, there may be increased irritation to the pulp, causing a degree of reversible inflammation.[9]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of DH may be challenging.[2] It is a diagnosis of exclusion, reached once all other possible explanations for the pain have been ruled out.[2] A thorough patient history and clinical examination are required.[2] The examination includes a pain provocation test by blasting air from a dental instrument onto the sensitive area, or gentle scratching with a dental probe.[11] If a negative result for the pain provocation test occurs, no treatment for dentinal hypersensitivity is indicated and another diagnosis should be sought, such as other causes of orofacial pain.[11]

Inflammation of the dental pulp, termed pulpitis, produces true hypersensitivity of the nerves in the dental pulp.[5] Pulpitis is classified as irreversible when pulpal inflammation will irreversibly progress to pulpal necrosis due to compression of the venous microcirculation and tissue ischemia, and reversible when the pulp is still capable of returning to a healthy, non-inflamed state, although usually dental treatment is required for this. Irreversible pulpitis is readily distinguishable from DH. There is poorly localized, severe pain which is aggravated by thermal stimuli, and which continues after the stimulus is removed. There also is typically spontaneous pain without any stimulus. Reversible pulpitis may not be so readily distinguishable from DH, however usually there will be some obvious sign such as a carious cavity, crack, etc. which indicates pulpitis. In contrast to pulpitis, the pain of DH is short and sharp.

Epidemiology

Dentin hypersensitivity is a relatively common condition.[1][5] Due to differences in populations studied and methods of detection, the reported incidence ranges from 4-74%.[5] Dentists may under-report dentin hypersensitivity due to difficulty in diagnosing and managing the condition.[1] When questionnaires are used, the reported incidence is usually higher than when clinical examination is used.[5] Overall, it is estimated to affect about 15% of the general population to some degree.[7]

It can affect people of any age, although those aged 20–50 years are more likely to be affected.[5] Females are slightly more likely to develop dentin hypersensitivity compared to males.[5] The condition is most commonly associated with the maxillary and mandibular canine and bicuspid teeth on the facial (buccal) aspect,[5] especially in areas of periodontal attachment loss.[9]

Prognosis

Dentin hypersensitivity may affect individuals' quality of life.[1] Over time, the dentin-pulp complex may adapt to the decreased insulation by laying down tertiary dentin, thereby increasing the thickness between the pulp and the exposed dentin surface and lessening the symptoms of hypersensitivity.[9] Similar process such as formation of a smear layer (e.g. from toothbrushing) and dentin sclerosis.[9] These physiologic repair mechanisms are likely to occur with or without any form of treatment, but they take time.

Treatment

| Treatments used for dentin hypersensitivity.[5] | |

|---|---|

| Intended mechanism of action | Example(s) |

| Nerve desensitization | |

| Protein precipitation | |

| Plugging dentinal tubules |

Bioactive glasses (SiO2–P2O5–CaO–Na2O) |

| Dentin adhesive sealers |

Fluoride varnishes Oxalic acid and resin |

| Lasers |

Neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser |

There is no universally accepted, gold-standard treatment which reliably relieves the pain of dental hypersensitivity in the long term,[11] and consequently many treatments have been suggested which have varying degrees of efficacy when scientifically studied.[1] Generally, they can be divided into in-office (i.e. intended to be applied by a dentist or dental therapist), or treatments which can be carried out at home, available over-the-counter or by prescription.[1][11] OTC products are more suited for generalized, mild to moderate dentin hypersensitivity associated with several teeth, and in-office treatments for localized, severe DH associated with one or two teeth.[1] Non-invasive, simple treatments which can be carried out at home should be attempted before in-office procedures are carried out.[11]

The purported mechanism of action of these treatments is either occlusion of dentin tubules (e.g. resins, varnishes, toothpastes) or desensitization of nerve fibres/blocking the neural transmission (e.g. potassium chloride, potassium citrate, potassium nitrate).[1][5]

Prevention

Gingival recession and cervical tooth wear can be avoided by healthy dietary and oral hygiene practices. By using a non-traumatic toothbrushing technique (i.e. a recommended technique such as the modified Bass technique rather than indiscriminately brushing the teeth and gums in a rough scrubbing motion) will help prevent receding gums and tooth wear around the cervical margin of teeth.[11] Non-abrasive toothpaste should be used,[11] and brushing should be carried out no more than twice per day for two minutes on each occasion. Excessive use of acidic conditions around the teeth should be avoided by limiting consumption of acidic foods and drinks,[11] and seeking medical treatment for any cause of regurgitation/reflux of stomach acid. Importantly, the teeth should not be brushed immediately after acidic foods or drinks. A non-abrasive diet will also help to prevent tooth wear.[11] Flossing each day also helps to prevent gum recession caused by gum disease.

Home treatment

At-home treatments include desensitizing toothpastes or dentifrices, potassium salts, mouthwashes and chewing gums.

A variety of toothpastes are marketed for dentin hypersensitivity, including compounds such as strontium chloride, strontium acetate, arginine, calcium carbonate, hydroxyapatite and calcium sodium phosphosilicate.[1] Desensitizing chewing gums [12] and mouthwashes are also marketed.[5]

Potassium-containing toothpastes are common; however, the mechanism by which they may reduce hypersensitivity is unclear. Animal research has demonstrated that potassium ions placed in deep dentin cavities cause nerve depolarization and prevent re-polarization. It is not known if this effect would occur with the twice-daily, transient and small increase in potassium ions in saliva that brushing with potassium-containing toothpaste creates. In individuals with dentin hypersensitivity associated with exposed root surfaces, brushing twice daily with toothpaste containing 5% potassium nitrate for six to eight weeks reduces reported sensitivity to tactile, thermal and air blast stimuli. However, meta analysis reported that these individuals' subjective report of sensitivity did not significantly change after six to eight weeks of using the potassium nitrate toothpaste.[7]

Desensitizing toothpastes containing potassium nitrate have been used since the 1980s while toothpastes with potassium chloride or potassium citrate have been available since at least 2000.[13] It is believed that potassium ions diffuse along the dentinal tubules to inactivate intradental nerves. However, as of 2000, this has not been confirmed in intact human teeth and the desensitizing mechanism of potassium-containing toothpastes remains uncertain.[14] Since 2000, several trials have shown that potassium-containing toothpastes can be effective in reducing dentin hypersensitivity, although rinsing the mouth after brushing may reduce their efficacy.[13]

Studies have found that mouthwashes containing potassium salts and fluorides can reduce dentine hypersensitivity, although rarely to any significant degree.[13] As of 2006, no controlled study of the effects of chewing gum containing potassium chloride has been made, although it has been reported as significantly reducing dentine hypersensitivity.[13]

Nano-hydroxyapatite (nano-HAp) is considered one of the most biocompatible and bioactive materials, and has gained wide acceptance in dentistry in recent years. An increasing number of reports have shown that nano-hydroxyapatite shares characteristics with the natural building blocks of enamel having the potential, due to its particle size, to occlude exposed dentinal tubules helping to reduce hypersensitivity and enhancing teeth remineralization.[15] For this reason, the number of toothpastes and mouthwashes that already incorporate nano-hydroxyapatite as a desensitizing agent is increasing.

In-office treatment

In-office treatments may be much more complex and they may include the application of dental sealants, having fillings put over the exposed root that is causing the sensitivity, or a recommendation to wear a specially made night guard or retainer if the problems are a result of teeth grinding.

Other possible treatments include fluorides are also used because they decrease permeability of dentin in vitro. Also, potassium nitrate can be applied topically in an aqueous solution or an adhesive gel. Oxalate products are also used because they reduce dentin permeability and occlude tubules more consistently. However, while some studies have showed that oxalates reduced sensitivity, others reported that their effects did not differ significantly from those of a placebo. Nowadays, dentin hypersensitivity treatments use adhesives, which include varnishes, bonding agents and restorative materials because these materials offer improved desensitization.[13]

Low-output lasers are also suggested for dentin hypersensitivity, including GaAlAs lasers and Nd:YAG laser.[9] They are thought to act by producing a transient reduction in action potential in C-fibers in the pulp, but Aδ-fibers are not affected.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Karim, BF; Gillam, DG (2013). "The efficacy of strontium and potassium toothpastes in treating dentine hypersensitivity: a systematic review.". International journal of dentistry. 2013: 573258. doi:10.1155/2013/573258. PMC 3638644

. PMID 23653647.

. PMID 23653647. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Türp, Jens C. (28 December 2012). "Discussion: how can we improve diagnosis of dentin hypersensitivity in the dental office?". Clinical Oral Investigations. 17 (S1): 53–54. doi:10.1007/s00784-012-0913-z. PMC 3585981

. PMID 23269545.

. PMID 23269545. - ↑ "International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) Version for 2010". World Health Organization. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ "Medical Subject Headings". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Miglani, Sanjay; Aggarwal, Vivek; Ahuja, Bhoomika (2010). "Dentin hypersensitivity: Recent trends in management". Journal of Conservative Dentistry. 13 (4): 218–24. doi:10.4103/0972-0707.73385. PMC 3010026

. PMID 21217949.

. PMID 21217949. - ↑ Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity (2003). Consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association 69:221-226.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Poulsen, S; Errboe, M; Lescay Mevil, Y; Glenny, AM (Jul 19, 2006). "Potassium containing toothpastes for dentine hypersensitivity.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (3): CD001476. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001476.pub2. PMID 16855970.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Petersson, Lars G. (28 December 2012). "The role of fluoride in the preventive management of dentin hypersensitivity and root caries". Clinical Oral Investigations. 17 (S1): 63–71. doi:10.1007/s00784-012-0916-9. PMC 3586140

. PMID 23271217.

. PMID 23271217. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hargreaves KM, Cohen S (editors), Berman LH (web editor) (2010). Cohen's pathways of the pulp (10th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier. pp. 510, 521. ISBN 978-0-323-06489-7.

- ↑ https://www.unitedconcordia.com/dental-insurance/dental/conditions/sensitive-teeth/

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Schmidlin, Patrick R.; Sahrmann, Phlipp (30 December 2012). "Current management of dentin hypersensitivity". Clinical Oral Investigations. 17 (S1): 55–59. doi:10.1007/s00784-012-0912-0.

- ↑ Porciani PF; Chazine M; Grandini S. "A clinical study of the efficacy of a new chewing gum containing calcium hydroxyapatite in reducing dentin hypersensitivity.". PubMed. The Journal of clinical dentistry. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Managing dentin hypersensitivity". 2006. Retrieved 2010-11-06., J Am Dent Assoc, Vol 137, No 7, 990-998

- ↑ The efficacy of potassium salts as agents for treating dentin hypersensitivity, Orchardson R, Gillam DG, Division of Neuroscience and Biomedical Systems, Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, J Orofac Pain. 2000 Winter;14(1):9-19

- ↑ Low, Samuel B.; Allen, Edward P.; Kontogiorgos, Elias D. (27 February 2015). "Reduction in Dental Hypersensitivity with Nano-Hydroxyapatite, Potassium Nitrate, Sodium Monoflurophosphate and Antioxidants". The Open Dentistry Journal. 9 (1): 92–97. doi:10.2174/1874364101509010092. PMC 4378071

. PMID 25834655.

. PMID 25834655.