Dendrimer

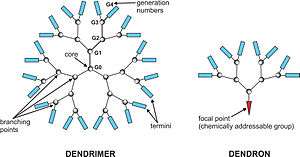

Dendrimers are repetitively branched molecules.[1][2] The name comes from the Greek word δέντρο (dendro). which translates to "tree".The Greek word δενδριμερές is translated as a part of the tree. It is named like that, because it is like to see a tree from the top. Synonymous terms for dendrimer include arborols and cascade molecules. However, dendrimer is currently the internationally accepted term. A dendrimer is typically symmetric around the core, and often adopts a spherical three-dimensional morphology. The word dendron is also encountered frequently. A dendron usually contains a single chemically addressable group called the focal point or core. The difference between dendrons and dendrimers is illustrated in the top figure, but the terms are typically encountered interchangeably.[3]

The first dendrimers were made by divergent synthesis approaches by Fritz Vögtle in 1978,[5] R.G. Denkewalter at Allied Corporation in 1981,[6][7] Donald Tomalia at Dow Chemical in 1983[8] and in 1985,[9][10] and by George R. Newkome in 1985.[11] In 1990 a convergent synthetic approach was introduced by Jean Fréchet.[12] Dendrimer popularity then greatly increased, resulting in more than 5,000 scientific papers and patents by the year 2005.

Properties

Dendritic molecules are characterized by structural perfection. Dendrimers and dendrons are monodisperse and usually highly symmetric, spherical compounds. The field of dendritic molecules can be roughly divided into low-molecular weight and high-molecular weight species. The first category includes dendrimers and dendrons, and the latter includes dendronized polymers, hyperbranched polymers, and the polymer brush.

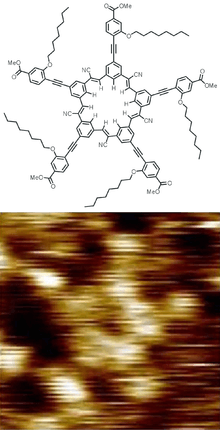

The properties of dendrimers are dominated by the functional groups on the molecular surface, however, there are examples of dendrimers with internal functionality.[13][14][15] Dendritic encapsulation of functional molecules allows for the isolation of the active site, a structure that mimics that of active sites in biomaterials.[16][17][18] Also, it is possible to make dendrimers water-soluble, unlike most polymers, by functionalizing their outer shell with charged species or other hydrophilic groups. Other controllable properties of dendrimers include toxicity, crystallinity, tecto-dendrimer formation, and chirality.[3]

Dendrimers are also classified by generation, which refers to the number of repeated branching cycles that are performed during its synthesis. For example, if a dendrimer is made by convergent synthesis (see below), and the branching reactions are performed onto the core molecule three times, the resulting dendrimer is considered a third generation dendrimer. Each successive generation results in a dendrimer roughly twice the molecular weight of the previous generation. Higher generation dendrimers also have more exposed functional groups on the surface, which can later be used to customize the dendrimer for a given application.[19]

Synthesis

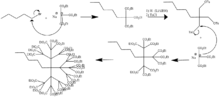

One of the very first dendrimers, the Newkome dendrimer, was synthesized in 1985. This macromolecule is also commonly known by the name arborol. The figure outlines the mechanism of the first two generations of arborol through a divergent route (discussed below). The synthesis is started by nucleophilic substitution of 1-bromopentane by triethyl sodiomethanetricarboxylate in dimethylformamide and benzene. The ester groups were then reduced by lithium aluminium hydride to a triol in a deprotection step. Activation of the chain ends was achieved by converting the alcohol groups to tosylate groups with tosyl chloride and pyridine. The tosyl group then served as leaving groups in another reaction with the tricarboxylate, forming generation two. Further repetition of the two steps leads to higher generations of arborol.[11]

Poly(amidoamine), or PAMAM, is perhaps the most well known dendrimer. The core of PAMAM is a diamine (commonly ethylenediamine), which is reacted with methyl acrylate, and then another ethylenediamine to make the generation-0 (G-0) PAMAM. Successive reactions create higher generations, which tend to have different properties. Lower generations can be thought of as flexible molecules with no appreciable inner regions, while medium-sized (G-3 or G-4) do have internal space that is essentially separated from the outer shell of the dendrimer. Very large (G-7 and greater) dendrimers can be thought of more like solid particles with very dense surfaces due to the structure of their outer shell. The functional group on the surface of PAMAM dendrimers is ideal for click chemistry, which gives rise to many potential applications.[20]

Dendrimers can be considered to have three major portions: a core, an inner shell, and an outer shell. Ideally, a dendrimer can be synthesized to have different functionality in each of these portions to control properties such as solubility, thermal stability, and attachment of compounds for particular applications. Synthetic processes can also precisely control the size and number of branches on the dendrimer. There are two defined methods of dendrimer synthesis, divergent synthesis and convergent synthesis. However, because the actual reactions consist of many steps needed to protect the active site, it is difficult to synthesize dendrimers using either method. This makes dendrimers hard to make and very expensive to purchase. At this time, there are only a few companies that sell dendrimers; Polymer Factory Sweden AB[21] commercializes biocompatible bis-MPA dendrimers and Dendritech[22] is the only kilogram-scale producers of PAMAM dendrimers. NanoSynthons, LLC[23] from Mount Pleasant, Michigan, USA produces PAMAM dendrimers and other proprietary dendrimers.

Divergent methods

The dendrimer is assembled from a multifunctional core, which is extended outward by a series of reactions, commonly a Michael reaction. Each step of the reaction must be driven to full completion to prevent mistakes in the dendrimer, which can cause trailing generations (some branches are shorter than the others). Such impurities can impact the functionality and symmetry of the dendrimer, but are extremely difficult to purify out because the relative size difference between perfect and imperfect dendrimers is very small.[19]

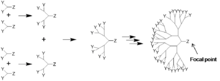

Convergent methods

Dendrimers are built from small molecules that end up at the surface of the sphere, and reactions proceed inward building inward and are eventually attached to a core. This method makes it much easier to remove impurities and shorter branches along the way, so that the final dendrimer is more monodisperse. However dendrimers made this way are not as large as those made by divergent methods because crowding due to steric effects along the core is limiting.[19]

Click chemistry

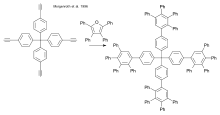

Dendrimers have been prepared via click chemistry, employing Diels-Alder reactions,[25] thiol-ene and thiol-yne reactions [26] and azide-alkyne reactions.[27][28][29]

There are ample avenues that can be opened by exploring this chemistry in dendrimer synthesis.

Applications

Applications of dendrimers typically involve conjugating other chemical species to the dendrimer surface that can function as detecting agents (such as a dye molecule), affinity ligands, targeting components, radioligands, imaging agents, or pharmaceutically active compounds. Dendrimers have very strong potential for these applications because their structure can lead to multivalent systems. In other words, one dendrimer molecule has hundreds of possible sites to couple to an active species. Researchers aimed to utilize the hydrophobic environments of the dendritic media to conduct photochemical reactions that generate the products that are synthetically challenged. Carboxylic acid and phenol-terminated water-soluble dendrimers were synthesized to establish their utility in drug delivery as well as conducting chemical reactions in their interiors.[30] This might allow researchers to attach both targeting molecules and drug molecules to the same dendrimer, which could reduce negative side effects of medications on healthy cells.[20]

Dendrimers can also be used as a solubilizing agent. Since their introduction in the mid-1980s, this novel class of dendrimer architecture has been a prime candidate for host-guest chemistry.[31] Dendrimers with hydrophobic core and hydrophilic periphery have shown to exhibit micelle-like behavior and have container properties in solution.[32] The use of dendrimers as unimolecular micelles was proposed by Newkome in 1985.[33] This analogy highlighted the utility of dendrimers as solubilizing agents.[34] The majority of drugs available in pharmaceutical industry are hydrophobic in nature and this property in particular creates major formulation problems. This drawback of drugs can be ameliorated by dendrimeric scaffolding, which can be used to encapsulate as well as to solubilize the drugs because of the capability of such scaffolds to participate in extensive hydrogen bonding with water.[35][36][37][38][39][40] Dendrimer labs throughout the planet are persistently trying to manipulate dendrimer’s solubilizing trait, in their way to explore dendrimer as drug delivery [41][42] and target specific carrier.[43][44][45]

For dendrimers to be able to be used in pharmaceutical applications, they must surmount the required regulatory hurdles to reach market. One dendrimer scaffold designed to achieve this is the Poly Ethoxy Ethyl Glycinamide (PEE-G) dendrimer.[46][47] This dendrimer scaffold has been designed and shown to have high HPLC purity, stability, aqueous solubility and low inherent toxicity.

Drug delivery

Approaches for delivering unaltered natural products using polymeric carriers is of widespread interest, dendrimers have been explored for the encapsulation of hydrophobic compounds and for the delivery of anticancer drugs. The physical characteristics of dendrimers, including their monodispersity, water solubility, encapsulation ability, and large number of functionalizable peripheral groups, make these macromolecules appropriate candidates for evaluation as drug delivery vehicles. There are three methods for using dendrimers in drug delivery: first, the drug is covalently attached to the periphery of the dendrimer to form dendrimer prodrugs, second the drug is coordinated to the outer functional groups via ionic interactions, or third the dendrimer acts as a unimolecular micelle by encapsulating a pharmaceutical through the formation of a dendrimer-drug supramolecular assembly.[48][49] The use of dendrimers as drug carriers by encapsulating hydrophobic drugs is a potential method for delivering highly active pharmaceutical compounds that may not be in clinical use due to their limited water solubility and resulting suboptimal pharmacokinetics. Dendrimers have been widely explored for controlled delivery of antiretroviral bioactives [50] The inherent antiretroviral activity of dendrimers enhances their efficacy as carriers for antiretroviral drugs.[51][52] The dendrimer enhances both the uptake and retention of compounds within cancer cells, a finding that was not anticipated at the onset of studies. The encapsulation increases with dendrimer generation and this method may be useful to entrap drugs with a relatively high therapeutic dose. Studies based on this dendritic polymer also open up new avenues of research into the further development of drug-dendrimer complexes specific for a cancer and/or targeted organ system.[53] These encouraging results provide further impetus to design, synthesize, and evaluate dendritic polymers for use in basic drug delivery studies and eventually in the clinic.[48][54]

Gene delivery

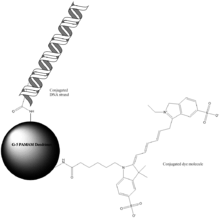

The ability to deliver pieces of DNA to the required parts of a cell includes many challenges. Current research is being performed to find ways to use dendrimers to traffic genes into cells without damaging or deactivating the DNA. To maintain the activity of DNA during dehydration, the dendrimer/DNA complexes were encapsulated in a water-soluble polymer, and then deposited on or sandwiched in functional polymer films with a fast degradation rate to mediate gene transfection. Based on this method, PAMAM dendrimer/DNA complexes were used to encapsulate functional biodegradable polymer films for substratemediated gene delivery. Research has shown that the fast-degrading functional polymer has great potential for localized transfection.[55][56][57]

Sensors

Dendrimers have potential applications in sensors. Studied systems include proton or pH sensors using poly(propylene imine),[58] cadmium-sulfide/polypropylenimine tetrahexacontaamine dendrimer composites to detect fluorescence signal quenching,[59] and poly(propylenamine) first and second generation dendrimers for metal cation photodetection[60] amongst others. Research in this field is vast and ongoing due to the potential for multiple detection and binding sites in dendritic structures.

Blood substitution

Dendrimers are also being investigated for use as blood substitutes. Their steric bulk surrounding a heme-mimetic centre significantly slows degradation compared to free heme,[61][62] and prevents the cytotoxicity exhibited by free heme.

Nanoparticles

Dendrimers also are used in the synthesis of monodisperse metallic nanoparticles. Poly(amidoamide), or PAMAM, dendrimers are utilized for their tertiary amine groups at the branching points within the dendrimer. Metal ions are introduced to an aqueous dendrimer solution and the metal ions form a complex with the lone pair of electrons present at the tertiary amines. After complexion, the ions are reduced to their zerovalent states to form a nanoparticle that is encapsulated within the dendrimer. These nanoparticles range in width from 1.5 to 10 nanometers and are called dendrimer-encapsulated nanoparticles.[63]

Crop Protection and Agrochemicals

Given the widespread use of pesticides, herbicides and insecticides in modern farming, dendrimers are also being used by companies to help improve the delivery of agrochemicals to enable healthier plant growth and to help fight plant diseases.[64]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dendrimers. |

References

- ↑ Astruc, Didier; Boisselier, Elodie; Ornelas, Cátia (2010). "Dendrimers Designed for Functions: From Physical, Photophysical, and Supramolecular Properties to Applications in Sensing, Catalysis, Molecular Electronics, and Nanomedicine". Chem. Rev. 110 (4): 1857–1959. doi:10.1021/cr900327d. PMID 20356105.

- ↑ Vögtle, Fritz / Richardt, Gabriele / Werner, Nicole Dendrimer Chemistry Concepts, Syntheses, Properties, Applications 2009 ISBN 3-527-32066-0

- 1 2 Nanjwade, B. K.; Bechra, H. M.; Derkar, G. K.; Manvi, F. V.; Nanjwade, V. K. (2009). "Dendrimers: Emerging polymers for drug-delivery systems". European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 38 (3): 185–196. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2009.07.008. PMID 19646528.

- ↑ Hirsch, Brandon E.; Lee, Semin; Qiao, Bo; Chen, Chun-Hsing; McDonald, Kevin P.; Tait, Steven L.; Flood, Amar H. (2014). "Anion-induced dimerization of 5-fold symmetric cyanostars in 3D crystalline solids and 2D self-assembled crystals". Chemical Communications. 50 (69): 9827–30. doi:10.1039/C4CC03725A. PMID 25080328.

- ↑ Buhleier, Egon; Wehner, Winfried; Vögtle, Fritz (1978). ""Cascade"- and "Nonskid-Chain-like" Syntheses of Molecular Cavity Topologies". Synthesis. 1978 (2): 155–158. doi:10.1055/s-1978-24702.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 4,289,872 Denkewalter, Robert G., Kolc, Jaroslav, Lukasavage, William J.

- ↑ Denkewalter, Robert G. et al. (1981) "Macromolecular highly branched homogeneous compound" U.S. Patent 4,410,688

- ↑ Tomalia, Donald A. and Dewald, James R. (1983) "Dense star polymers having core, core branches, terminal groups" U.S. Patent 4,507,466

- ↑ Tomalia, D A; Baker, H; Dewald, J; Hall, M; Kallos, G; Martin, S; Roeck, J; Ryder, J; Smith, P (1985). "A New Class of Polymers: Starburst-Dendritic Macromolecules". Polymer Journal. 17: 117–132. doi:10.1295/polymj.17.117.

- ↑ "Treelike molecules branch out – chemist Donald A. Tomalia synthesized first dendrimer molecule – Chemistry – Brief Article". Science News. 1996.

- 1 2 Newkome, George R.; Yao, Zhongqi; Baker, Gregory R.; Gupta, Vinod K. (1985). "Micelles. Part 1. Cascade molecules: a new approach to micelles. A [27]-arborol". J. Org. Chem. 50 (11): 2003–2004. doi:10.1021/jo00211a052.

- ↑ Hawker, C. J.; Fréchet, J. M. J. (1990). "Preparation of polymers with controlled molecular architecture. A new convergent approach to dendritic macromolecules". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 (21): 7638–7647. doi:10.1021/ja00177a027.

- ↑ Antoni, P.; Hed, Y.; Nordberg, A.; Nyström, D.; Hult, A.; Malkoch, M. (2009). "Bifunctional Dendrimers: From Robust Synthesis and Accelerated One-Pot Postfunctionalization Strategy to Potential Applications". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48 (12): 2126–2130. doi:10.1002/anie.200804987. PMID 19117006.

- ↑ McElhanon, J. R.; McGrath, D. V. (2000). "Toward Chiral Polyhydroxylated Dendrimers. Preparation and Chiroptical Properties". JOC. 65 (11): 3525–3529. doi:10.1021/jo000207a.

- ↑ Liang, C. O.; Fréchet, J. M. J. (2005). "Incorporation of Functional Guest Molecules into an Internally Functionalizable Dendrimer through Olefin Metathesis". Macromolecules. 38 (15): 6276–6284. doi:10.1021/ma050818a.

- ↑ Hecht, S; Fréchet, J. M. (2001). "Dendritic Encapsulation of Function: Applying Nature's Site Isolation Principle from Biomimetics to Materials Science". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40 (1): 74–91. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010105)40:1<74::AID-ANIE74>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 11169692.

- ↑ Frechet, Jean M.; Donald A. Tomalia (March 2002). Dendrimers and Other Dendritic Polymers. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-63850-6.

- ↑ Fischer, Marco; Vögtle, Fritz (1999). "Dendrimers: From Design to Application—A Progress Report". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38 (7): 884–905. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990401)38:7<884::AID-ANIE884>3.0.CO;2-K.

- 1 2 3 Holister, Paul; Christina Roman Vas; Tim Harper (October 2003). "Dendrimers: Technology White Papers" (PDF). Cientifica. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- 1 2 Hermanson, Greg T. (2008). "7". Bioconjugate Techniques (2nd ed.). London: Academic Press of Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-370501-3.

- ↑ Polymer Factory AB, Stockholm, Sweden.Polymer Factory

- ↑ Dendritech Inc., from Midland, Michigan, USA.Dendritech.

- ↑ Home. NanoSynthons. Retrieved on 2015-09-29.

- ↑ Morgenroth, Frank; Reuther, Erik; Müllen, Klaus (1997). "Polyphenylene Dendrimers: From Three-Dimensional to Two-Dimensional Structures". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 36 (6): 631–634. doi:10.1002/anie.199706311.

- ↑ Franc, Grégory; Kakkar, Ashok K. (2009). "Diels-Alder "Click" Chemistry in Designing Dendritic Macromolecules". Chemistry: A European Journal. 15 (23): 5630–5639. doi:10.1002/chem.200900252.

- ↑ Killops, Kato L.; Campos, Luis M.; Hawker, Craig J. (2008). "Robust, Efficient, and Orthogonal Synthesis of Dendrimers via Thiol-ene "Click" Chemistry". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (15): 5062–4. doi:10.1021/ja8006325. PMID 18355008.

- ↑ Noda K, Minatogawa Y, Higuchi T (March 1991). "Effects of hippocampal neurotoxicant, trimethyltin, on corticosterone response to a swim stress and glucocorticoid binding capacity in the hippocampus in rats". Jpn. J. Psychiatry Neurol. 45 (1): 107–8. PMID 1753450.

- ↑ Machaiah JP (May 1991). "Changes in macrophage membrane proteins in relation to protein deficiency in rats". Indian J. Exp. Biol. 29 (5): 463–7. PMID 1916945.

- ↑ Franc, Grégory; Kakkar, Ashok (2008). "Dendrimer design using CuI-catalyzed alkyne–azide "click-chemistry"". Chemical Communications (42): 5267. doi:10.1039/b809870k.

- ↑ Kaanumalle, Lakshmi S.; Ramesh, R.; Murthy Maddipatla, V. S. N.; Nithyanandhan, Jayaraj; Jayaraman, Narayanaswamy; Ramamurthy, V. (2005). "Dendrimers as Photochemical Reaction Media. Photochemical Behavior of Unimolecular and Bimolecular Reactions in Water-Soluble Dendrimers". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 70 (13): 5062–9. doi:10.1021/jo0503254. PMID 15960506.

- ↑ Tomalia, Donald A.; Naylor, Adel M.; Goddard, William A. (1990). "Starburst Dendrimers: Molecular-Level Control of Size, Shape, Surface Chemistry, Topology, and Flexibility from Atoms to Macroscopic Matter". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 29 (2): 138–175. doi:10.1002/anie.199001381.

- ↑ Frechet, J. M. J. (1994). "Functional Polymers and Dendrimers: Reactivity, Molecular Architecture, and Interfacial Energy". Science. 263 (5154): 1710–1715. doi:10.1126/science.8134834.

- ↑ Liu, Mingjun; Kono, Kenji; Fréchet, Jean M.J (2000). "Water-soluble unimolecular micelles: their potential as drug delivery agents". J. Cont. Rel. 65: 121–131. doi:10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00245-x.

- ↑ Newkome, George R.; Yao, Zhongqi; Baker, Gregory R.; Gupta, Vinod K. (1985). "Micelles Part 1. Cascade molecules: a new approach to micelles, A-arborol". J. Org. Chem. 50 (11): 155–158. doi:10.1021/jo00211a052.

- ↑ Stevelmens, S.; Hest, J. C. M.; Jansen, J. F. G. A.; Boxtel, D. A. F. J.; de Bravander-van den, B.; Miejer, E. W. (1996). "Synthesis, characterisation and guest-host properties of inverted unimolecular micelles". J Am Chem Soc. 118 (31): 7398–7399. doi:10.1021/ja954207h.

- ↑ Gupta, U; Agashe, H.B.; Asthana, A.; Jain, N.K. (2006). "Dendrimers: Novel Polymeric Nanoarchitectures for Solubility Enhancement Biomacromolecules". Biomacromolecules. 7 (3): 649–658. doi:10.1021/bm050802s.

- ↑ Thomas, Thommey P.; Majoros, Istvan J.; Kotlyar, Alina; Kukowska-Latallo, Jolanta F.; Bielinska, Anna; Myc, Andrzej; Baker, James R. (2005). "Targeting and Inhibition of Cell Growth by an Engineered Dendritic Nanodevice". J. Med. Chem. 48 (11): 3729–3735. doi:10.1021/jm040187v.

- ↑ Bhadra, D; Bhadra, S; Jain, P; Jain, N. K. (2002). "Pegnology: a review of PEG-ylated systems". Pharmazie. 57 (1): 5–29. PMID 11836932.

- ↑ Asthana, A.; Chauhan, A. S.; Diwan, P. V.; Jain, N. K. (2005). "Poly (amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendritic nanostructures for controlled site-specific delivery of anti-inflammatory active ingredient". AAPS PharmSciTech. 6 (3): E536–E542. doi:10.1208/pt060367. PMC 2750401

. PMID 16354015.

. PMID 16354015. - ↑ Bhadra, D.; Bhadra, S.; Jain, S.; Jain, N.K. (2003). "A PEGylated, dendritic nanoparticulate carrier of fluorouracil". Synthesis. 257: 111–124. doi:10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00132-7.

- ↑ Khopade, Ajay J.; Caruso, Frank; Tripathi, Pushpendra; Nagaich, Surekha; Jain, Narendra K. (2002). ""Cascade"- and " Effect of dendrimer on entrapment and release of bioactive from liposomes". Int. J. Pharm. 232 (1–2): 157–162. doi:10.1016/S0378-5173(01)00901-2. PMID 11790499.

- ↑ Prajapati RN, Tekade RK, Gupta U, Gajbhiye V, Jain NK (2009). "Dendimer-Mediated Solubilization, Formulation Development and in Vitro-in Vivo Assessment of Piroxicam". Synthesis. 6 (3): 940–950. doi:10.1021/mp8002489.

- ↑ Chauhan, Abhay S; Sridevi, S; Chalasani, Kishore B; Jain, Akhlesh K; Jain, Sanjay K; Jain, N.K; Diwan, Prakash V (2003). "Dendrimer-mediated transdermal delivery: enhanced bioavailability of indomethacin". Synthesis. 90 (3): 335–343. doi:10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00200-1.

- ↑ Kukowska-Latallo, J. F. (2005). "Nanoparticle Targeting of Anticancer Drug Improves Therapeutic Response in Animal Model of Human Epithelial". Synthesis. 65 (12): 5317–5324. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-3921.

- ↑ Quintana, Antonio; Raczka, Ewa; Piehler, Lars; Lee, Inhan; Myc, Andrzej; Majoros, Istvan; Patri, Anil K.; Thomas, Thommey; Mulé, James; Baker Jr., James R. (2002). "Design and Function of a Dendrimer-Based Therapeutic nanodevice targeted to tumor cells through the folate receptor". Synthesis. 19 (9): 1310–1316. doi:10.1023/a:1020398624602.

- ↑ Toms, Steven; Carnachan, Susan M.; Hermans, Ian F.; Johnson, Keryn D.; Khan, Ashna A.; O’Hagan, Suzanne E.; Tang, Ching-Wen; Rendle, Phillip M. (2016). "Poly Ethoxy Ethyl Glycinamide (PEE-G) Dendrimers: Dendrimers Specifically Designed for Pharmaceutical Applications". ChemMedChem. 11 (15): 1583–6. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201600270. PMID 27390296.

- ↑ GlycoSyn. "PEE-G Dendrimers".

- 1 2 Morgan, M. T.; Nakanishi, Y; Kroll, D. J.; Griset, A. P.; Carnahan, M. A.; Wathier, M; Oberlies, N. H.; Manikumar, G; Wani, M. C.; Grinstaff, M. W. (2006). "Dendrimer-Encapsulated Camptothecins". Cancer Research. 66 (24): 11913–21. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2066. PMID 17178889.

- ↑ Tekade, R. K.; Dutta, T; Gajbhiye, V; Jain, N. K. (2009). "Exploring dendrimer towards dual drug delivery". Journal of Microencapsulation. 26 (4): 287–296. doi:10.1080/02652040802312572. PMID 18791906.

- ↑ Dutta, Tathagata; Jain, N.K. (2007). "Targeting Potential and Anti HIV activity of mannosylated fifth generation poly (propyleneimine) Dendrimers". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1770 (4): 681–686. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.12.007. PMID 17276009.

- ↑ Dutta, T; Garg, M; Jain, N. K. (2008). "Targeting of efavirenz loaded tuftsin conjugated poly(propyleneimine) dendrimers to HIV infected macrophages in vitro". European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 34 (2–3): 181–9. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2008.04.002. PMID 18501568.

- ↑ Dutta, Tathagata; Agashe, Hrushikesh B.; Garg, Minakshi; Balakrishnan, Prahlad; Kabra, Madhulika; Jain, Narendra K. (2007). "Poly (propyleneimine) dendrimer based nanocontainers for targeting of efavirenz to human monocytes/macrophages in vitro". Journal of Drug Targeting. 15 (1): 84–96. doi:10.1080/10611860600965914.

- ↑ "Search of: starpharma - List Results - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- ↑ Cheng, Y; Wu, Q; Li, Y; Xu, T (2008). "External Electrostatic Interaction versus Internal Encapsulation between Cationic Dendrimers and Negatively Charged Drugs: Which Contributes More to Solubility Enhancement of the Drugs?". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 112 (30): 8884–8890. doi:10.1021/jp801742t. PMID 18605754.

- ↑ Fu, H. L.; Cheng, S. X.; Zhang, X. Z.; Zhuo, R. X. (2008). "Dendrimer/DNA complexes encapsulated functional biodegradable polymer for substrate-mediated gene delivery". The Journal of Gene Medicine. 10 (12): 1334–1342. doi:10.1002/jgm.1258. PMID 18816481.

- ↑ Fu, HL; Cheng SX; Zhang XZ (2007). "Dendrimer/DNA complexes encapsulated in a water soluble polymer and supported on fast degrading star poly(DL-lactide) for localized gene delivery". Journal of Control Release. 124 (3): 181–188. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.08.031. PMID 17900738.

- ↑ Dutta, Tathagata; Garg, Minakshi (2008). "Poly(propyleneimine) dendrimer and dendrosome based genetic immunization against Hepatitis B". Vaccine. 26 (27–28): 3389–3394. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.058. PMID 18511160.

- ↑ Fernandes, Edson G. R.; Vieira, Nirton C. S.; de Queiroz, Alvaro A. A.; Guimaraes, Francisco E. G.; Zucolotto, Valtencir (2010). "Immobilization of Poly(propylene imine) Dendrimer/Nickel Phthalocyanine as Nanostructured Multilayer Films To Be Used as Gate Membranes for SEGFET pH Sensors". Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 114 (14): 6478–6483. doi:10.1021/jp9106052.

- ↑ Campos, Bruno B; Algarra, Manuel; Esteves da Silva, Joaquim C. G (2010). "Fluorescent Properties of a Hybrid Cadmium Sulfide-Dendrimer Nanocomposite and its Quenching with Nitromethane". Journal of Fluorescence. 20 (1): 143–151. doi:10.1007/s10895-009-0532-5. PMID 19728051.

- ↑ Grabchev, Ivo; Staneva, Desislava; Chovelon, Jean-Marc (2010). "Photophysical investigations on the sensor potential of novel, poly(propylenamine) dendrimers modified with 1,8-naphthalimide units". Dyes and Pigments. 85 (3): 189–193. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2009.10.023.

- ↑ Twyman, L. J.; Ge, Y. (2006). "Porphyrin cored hyperbranched polymers as heme protein models". Chemical Communications (15): 1658. doi:10.1039/b600831n.

- ↑ Twyman, L. J.; Ellis, A.; Gittins, P. J. (2012). "Pyridine encapsulated hyperbranched polymers as mimetic models of haeme containing proteins, that also provide interesting and unusual porphyrin-ligand geometries". Chemical Communications. 48 (1): 154–156. doi:10.1039/c1cc14396d. PMID 22039580.

- ↑ Crooks, Richard; Scott, Wilson (2005). "Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications of Dendrimer-Encapsulated Nanoparticles". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 109 (2): 692–704. doi:10.1021/jp0469665.

- ↑ "Dendrimer technology licensed for herbicide". www.labonline.com.au. Retrieved 2016-09-25.