Cooling Castle

| Cooling Castle | |

|---|---|

| Cooling, Kent, England | |

|

Outer gatehouse of Cooling Castle | |

Cooling Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51°27′20″N 0°31′23″E / 51.455441°N 0.523084°ECoordinates: 51°27′20″N 0°31′23″E / 51.455441°N 0.523084°E |

| Type | Quadrangular castle |

| Height | 12 metres (39 ft) (gatehouse), up to 9 metres (30 ft) (walls) |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Private owners |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1380s |

| Built by | John Cobham |

| In use | 1380s-c.1554 |

| Materials | Kentish ragstone, flint, chalk rubble |

| Events | Wyatt's rebellion |

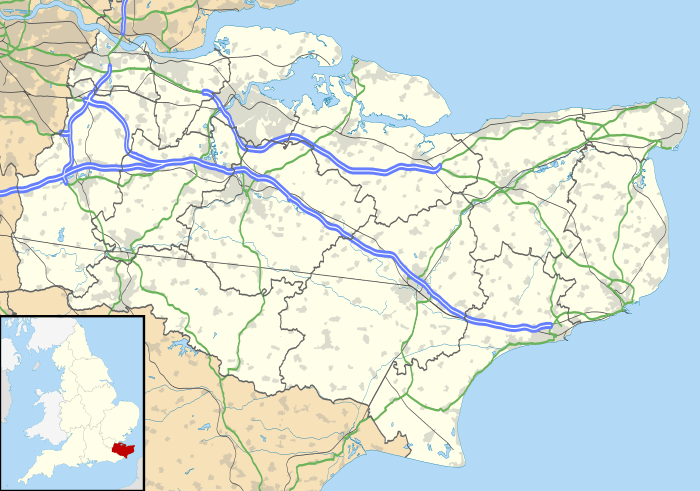

Cooling Castle is a 14th-century quadrangular castle in the village of Cooling, Kent on the Hoo Peninsula about 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Rochester. It was built in the 1380s by the Cobham family, the local lords of the manor, to guard the area against French raids into the Thames Estuary. The castle has an unusual layout, comprising two walled wards of unequal size next to each other, surrounded by moats and ditches. It was the earliest English castle designed for the use of gunpowder weapons by its defenders.

Despite this distinction, the use of gunpowder weapons against the castle proved devastating. It was captured after only eight hours when Sir Thomas Wyatt besieged it in January 1554 during his unsuccessful rebellion against Queen Mary. His attack wrecked the castle and it was subsequently abandoned. A farmhouse and outbuildings were constructed among the ruins a century later. Today the farmhouse is the home of the musician Jools Holland, while the nearby barn is used as a wedding venue.

History

Construction

The castle was originally built on the south bank of the Thames but the shoreline has since receded as a result of land reclamation; the river is now about 2 miles (3.2 km) north of the castle, separated from it by marshes. It was constructed by John Cobham. His family had acquired the manor of Cooling in the mid-13th century. In 1379, during the second phase of the Hundred Years' War, a French raid devastated towns and villages along the Thames Estuary. Cobham appealed to the Crown for licence to fortify his manor and received permission in February 1380. The building work was completed by 1385.[1]

Surviving records indicate that the prominent gatehouse was built by local labour under several master masons, including Thomas Crompe, William Sharnall and Thomas Wrek, with the king's master mason Henry Yevele taking a supervisory role.[2] The castle is of particular importance as being the earliest English castle designed for the use of gunpowder weapons.[3] Lord Cobham's instructions to his masons include his requirement for "x arket holes [10 holes for arquebuses] de iii peez longour [of 3 feet? length] et tout saunz croys [without cross-slits]."[4]

Cobham fell out of the king's favour shortly after the castle was completed and was exiled for a while, but was able to return eventually and died at Cooling in 1408. His granddaughter Joan inheirited his estates and married four times. Her last husband, Sir John Oldcastle, was executed in 1417 for his role in the Lollard heresy. The Cobham title remained intact but the castle passed to other families down the female line.[5]

Wyatt's Rebellion

Cooling Castle only saw action once in its history, when it was attacked in 1554 by the forces of the Kentish landowner Sir Thomas Wyatt during his rebellion against Queen Mary's engagement to King Philip II of Spain. In an unsuccessful bid to overthrow the unpopular queen and place Princess (later Queen) Elizabeth on the throne, he raised an army of some 4,000 men and captured two cannons from the army of Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk in an encounter at Strood, a few miles south of Cooling. It is unclear why he detoured to Cooling while ostensibly marching on London, and it had the disadvantage of allowing Mary more time to prepare her own defences. There may have been a personal motive for Wyatt; the castle's occupant by this time was his own brother-in-law, Lord George Cobham.[5][6]

The defenders were forced to surrender on 30 January 1554 after only eight hours of siege and bombardment. According to contemporary reports, Cobham only had eight men to defend the castle with "only four or five handguns, four pikes and some blakbylls".[5] Wyatt proceeded on to London but was defeated and executed for his treason. Cobham and his son were imprisoned in the Tower of London on suspicion of having deliberately failed to defend the castle, but were soon released and allowed to return to their estates. The castle was never rebuilt after being wrecked by Wyatt's bombardment; the Cobhams abandoned it and subsequently lived at Cobham Hall.[7]

Current status

The castle remained in the Cobhams' ownership until the 18th century.[1] Between 1650–1670, Sir Thomas Whitmore built a farmhouse within the castle's outer ward, which has undergone many alterations over the years. Its facade dates from the 19th century and was reworked in the 20th century. An L-shaped range of outbuildings was also constructed in the outer ward, including a timber-framed barn that was built in the 17th century. At some point in the 18th or 19th centuries, part of the inner ward was landscaped, possibly to create a garden incorporating the ruins. The ownership of the castle is split three ways; the barn is used as a party and wedding venue, the inner ward was owned for many years by the Rochester Bridge Wardens and the house's current occupant is the musician Jools Holland.[8] The castle was listed as a Grade I listed building in 1946,[1] while the barn was separately Grade II listed in 1986.[9] Cooling Castle is listed on English Heritage's "Heritage at Risk" register due to the very poor condition of its fabric.[10]

Description

Cooling Castle has an unusual layout that was perhaps dictated by the marshy environment within which it was constructed. Most quadrangular castles were constructed on a single moated island within which was a system of inner wards or courtyards. Cooling Castle differed in that within its 8 acre (3.2 ha) perimeter it had two wards of different sizes arranged side by side. Each stood on a mound within a figure of eight-shaped system of moats and ditches. The inner ward, in the west of the castle, appears to have been surrounded by a moat that may have been up to 20 metres (66 ft) wide. The larger outer ward, in the eastern part of the castle, was flanked on its western side by the moat and a dry ditch up to 6 metres (20 ft) deep flanked the other three sides of the ward. A causeway on the northern side separated the ditch from the moat.[7][11]

Wards

The outer ward had a roughly rectangular shape measuring about 134 x 88 metres (440 x 290 ft). It was completely walled, with horseshoe-shaped towers on three corners, and was accessed via the outer gatehouse at its south-west corner. The corner towers are advanced about 5 metres (16 ft) in front of the curtain wall and still stand to a height of 12 metres (39 ft). Parts of the curtain wall also still remain. Much of the outer ward is now occupied by the 17th-century farmhouse and its outbuildings.[11]

|

The roughly square inner ward measures about 60 x 52 metres (196 x 170 feet). It stands on a higher mound that gave its occupants a view over the outer ward and the surrounding countryside. The ward was completely walled and completely independent of the outer ward. It could only be accessed through an inner gatehouse half-way along the western wall of the outer ward, crossing the moat by means of a drawbridge. This arrangement meant that an attacker would have to capture the outer ward before being able to assault the inner one. The ward's curtain wall still stands to a height of between 3–6 metres (15–30 ft). Two of its towers, in the south-east and north-west corners, still stand to a height of about 7 metres (34 ft) but that at the north-east corner has disappeared and the one at the south-west has collapsed. There are traces of buildings along the inside of the walls of the inner ward, which were presumably the domestic buildings of the castle. In the north-east corner of the inner ward, the ruins of a vaulted undercroft survive under what was once the Great Chamber of the castle.[3][7][11]

Gatehouse

The outer gatehouse is the castle's most prominent surviving feature and adjoins the Cliffe to Cooling road. It consists of two semi-circular towers standing 12 metres (39 ft) high, with prominent machicolations and crenelations, flanking an arched gateway that stands 3 metres (9.8 ft) high and 5 metres (16 ft) wide. Both towers are open at the back, but were probably originally closed off by timber walls.[3][11] The eastern tower incorporates a copper plate on which is enamelled the following inscription, set out both in wording and in design as an imitation of a contemporary deed:

Knouwyth that beth and schul be

That I am mad in help of the cuntre

In knowing of whyche thing

Thys is chartre and wytnessyng.[1]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

KDHwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).Know [those] that are [living] and shall be [living]

That I am made to help the country

In knowing of which thing

This is [a] charter and witnessing.

The inscription was probably intended to serve as a reassurance to the local community that the castle was not aimed at them, but was for purely defensive purposes.[7]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cooling Castle. |

- 1 2 3 "Historic England – Cooling Castle and its associated landscaped setting". English Heritage. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ Ingleton, Roy D. (2012). Fortress Kent. Casemate Publishers. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-84884-888-7.

- 1 2 3 Saunders, Andrew; Smith, Victor (2001). "Cooling Castle – KD 4". Kent's Defence Heritage – Gazetteer Part One. Kent County Council.

- ↑ Pounds, Norman J. G. (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Political and Social History. Cambridge University Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- 1 2 3 Ingleton, p. 73

- ↑ Cope, Brian (1927). "Sir Thomas Wyatt's Assault on Cooling Castle, 30th January 1554" (PDF). Archaeologica Cantiana. 39: 167–76.

- 1 2 3 4 Ingleton, p. 74

- ↑ Smith, Joanna; Clarke, Jonathan (2014). "Cooling, Hoo Peninsula, Kent – Historic Area Assessment". English Heritage. ISSN 2046-9802.

- ↑ "Historic England – Barn 30 yards north east of Cooling Castle gatehouse". English Heritage. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "Cooling Castle, Cooling – Medway (UA)". English Heritage. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Cooling Castle". English Heritage. Retrieved 9 July 2015.