Common genet

| Common genet | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Viverridae |

| Subfamily: | Viverrinae |

| Genus: | Genetta |

| Species: | G. genetta |

| Binomial name | |

| Genetta genetta[2] (Linnaeus), 1758 | |

| |

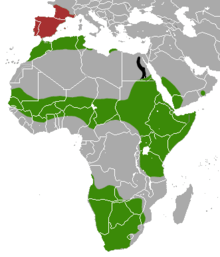

| Common genet range (green - native, red - extant introduced, black - extinct introduced) | |

The common genet (Genetta genetta), is a small viverrid indigenous to Africa that was introduced to southwestern Europe and the Balearic Islands. As it is widely distributed north of the Sahara, in savanna zones south of the Sahara to southern Africa and along the coast of Arabia, Yemen and Oman, it is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. It has also been recorded in Germany, Belgium and Switzerland.[1]

Characteristics

Common genets have a slender, cat-like body, 43 to 55 cm (17 to 22 in) in length, and a tail measuring 33 to 52 cm (13 to 20 in). Males, with an average weight of 2 kilograms (4.4 lb), are about 10% larger than females. The legs are short, with cat-like feet and semi-retractile claws. They have a small head with a pointed muzzle, large oval ears, large eyes, and well-developed whiskers up to 7 cm (2.8 in) in length.[3]

The fur is dense and soft, and the coat is pale grey, with numerous black markings. The back and flanks are marked with about five rows of black spots, and a long black stripe runs along the middle of the back from the shoulders to the rump. There is also a black stripe on the forehead, and dark patches beneath the eyes, which are offset against the white fur of the chin and throat. The tail is striped, with anything from eight to thirteen rings along its length.[3]

The Common genet differs from the Cape genet (G.tigrina also known as the large-spotted genet) in that:

- Genetta genetta - has a white tail tip, black hind feet, and an erectile crest of hair from the shoulder to the base of the tail (hairs 44 to 70mm long)

- Genetta tigrina- has a black tail tip, hind feet not black, dorsal crest hairs less than 43mm long.[4]

Distribution and habitat

In North Africa, common genets occur along the western Mediterranean coast, and in a broad band from Senegal and Mauritania in the west throughout the savannah zone south of the Sahara to Somalia and Tanzania in the east. On the Arabian Peninsula, they were recorded in coastal regions of Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Oman. Another discontinuous population inhabits southern Africa, from southern Angola across Zambia, Zimbabwe to Mozambique. They inhabit a wide range of deciduous and evergreen habitats that provide plentiful shelter such as rocky terrain with caves and dense scrub land, but also come close to settlements and agricultural land.[1] They are common in Morocco,[5] but rare in Libya, Egypt and Zambia.[3] In South Africa, they are common in west-central KwaZulu-Natal,[6] in the Cape Province,[7] and in QwaQwa National Park in the Free State province.[8]

They were brought to the Mediterranean region from Maghreb as a domestic animal about 1000 to 1500 years ago, and from the Iberian Peninsula spread to the Balearic Islands and southern France.[9] In Italy, they were sighted in mountainous areas in the Piedmont region and in the Aosta Valley. Individuals sighted in Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands are considered to have escaped or been released from captivity.[10] In southwestern Europe, they thrive in oak and pine forests, but also live in olive groves, riparian zones, ash groves, rocky areas, and shrublands. They are rare in open areas, marshes, and cereal croplands. Despite their abundance along watercourses, presence of water is not considered essential.[3] They prefer to live in areas with dense vegetation, such as bushes, thickets, and evergreen oak forests.[11] As resting sites they use trees with dense foliage in the canopy and dense thickets overgrown with climbing plants.[12] In northern areas, they prefer low altitudes with high temperatures and low rainfall.[13] In the Manzanares Park in central Spain, they live foremost in areas of 1,000–1,200 m (3,300–3,900 ft) elevation with lots of rocks and shrubs. They tolerate proximity to settlements.[14]

Common genets and wood mice share the same habitats and niches, specifically Mediterranean forests.[15][16]

Ecology and behaviour

Common genets are solitary. Adults are nocturnal and crepuscular, with their highest levels of activity following sunset and just prior to sunrise; juveniles may be active during the day. They rest during the day in hollow trees or among thickets, and frequently use the same resting sites. In southern Spain, adult individuals occupy home ranges of about 7.8 km2 (3.0 sq mi) in average. The ranges of males and females overlap, but those of members of the same sex do not.[17] In northern Spain, home ranges of three females ranged from 2.1 to 10.2 km2 (0.81 to 3.94 sq mi).[18]

During a study in northeastern Spain, males have been found to be more active than females at night because of their greater size, which indicates that males have greater energy requirements to satisfy their physiological needs. Females typically weigh less, and they have been found to be less active overall. Females' home ranges are also smaller than those of males.[19] Males had a mean annual home range of 113 ha (280 acres), and females of 72 ha (180 acres). While males have larger home ranges in all seasons, the differences between males' and females' territories are most significant during the winter. Their home ranges are slightly larger during the spring because they are more active, not only nocturnally, but in seeking a mate. Because of their increased activity, they require more energy and are more active to acquire the necessary sustenance.[20]

Both male and females scent mark in their home ranges. Females mark their territory using scent glands on their flanks, hind legs, and perineum. Males mark less frequently than females, often spraying urine, rather than using their scent glands, and do so primarily during the breeding season. Scent marks by both sexes allow individuals to identify the reproductive and social status of other genets. Common genets also defecate at specific latrine sites, which are often located at the edge of their territories, and perform a similar function to other scent marks.[3]

Five communication calls have been reported. The hiccup call is used by males during the mating period and by females to call the litter. Kits purr during their first week of life and, during their dependent weeks, moan or mew. Kits also growl after the complete development of predatory behavior and during aggressive interactions. Finally, genets utter a "click" as a threat. Threatening behavior consists of erection of the dark central dorsal band of hair, an arched-back stance, opening the mouth, and baring the teeth.[3]

Common genets have five distinct calls. The "hiccup" call is used to indicate friendly interactions, such as between a mother and her young, or between males and females prior to mating. Conversely, clicks, or, in younger individuals, growls, are used to indicate aggression. The remaining two calls, a "mew" and a purr, are used only by young still dependant on their mother.[3]

Common genets have a varied diet comprising small mammals, lizards, birds, bird eggs, amphibians, centipedes, millipedes, scorpions, insects and fruit, including figs and olives. The wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus) is a favourite prey item,[21] but genets from the Balearics live chiefly on lizards.

As genets are expert climbers, they also prey on red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) and dormice (Eliomys quercinus). Genets locate their prey primarily by scent, and kill with a bite to the neck, like cats. Small rodents are captured by the back and killed with a bite at the head, then eaten starting with the head.[3][22]

In Spain, common genets can suffer from infestation of parasitic helminths, as well as ticks, fleas (Hippobosca), and lice. Common genets also host the phthirapteran Eutrichophilus genettae and Lorisicola (Paradoxuroecus) genettae.[23]

In Africa, predators include leopard, serval, caracal, ratel and large owl species.[24] Potential predators are also red fox and northern goshawk.[12]

Reproduction and development

In Spain, common genets breed between January and September, with a peak in February and March and another one in the summer.[22] Mating behaviour and development of young has been studied in captive individuals. Copulation lasts about two to three minutes, and is repeated up to five times in the same night. After a gestation period of 10 to 11 weeks, up to four young are born. Newborn common genets weigh 60 to 85 g (2.1 to 3.0 oz). They start eating meat at around seven weeks of age, and are fully weaned at four months of age. When five months old, they are skilled in hunting on their own. When 19 months old, they start marking, and are thought to be sexually mature at the age of two years. Captive common genets have lived up to 13 years.[25][26]

Threats

No major threats to common genets are known. In North Africa and some localities in southern Africa, they are hunted for their fur. In Portugal, they get killed in predator traps. On Ibiza, urbanization and development of infrastructure cause loss and fragmentation of habitat.[1]

Conservation

Genetta genetta is listed on Appendix III of the Bern Convention and in Annex V of the Habitats and Species Directive of the European Union.[27]

Taxonomy

Along with other viverrids, genets are among living Carnivorans considered to be the morphologically closest to the extinct common ancestor of the whole order.[28][29]

More than 30 subspecies of the common genet have been described. The following are considered valid:[2]

- G. g. genetta (Linnaeus), 1758 — Spain, Portugal and France[30]

- G. g. afra (Cuvier), 1825 — North Africa[31]

- G. g. senegalensis (Fischer), 1829 — sub-Saharan Africa[32]

- G. g. dongolana (Hemprich and Ehrenberg), 1832 — Arabia[33]

Genetta felina has been reclassified as a species based on morphological diagnoses comparing 5500 Viverrinae specimens in zoological collections.[34]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Gaubert, P.; Carvalho, F.; Camps, D. & Do Linh San, E. (2015). "Genetta genetta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2016.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- 1 2 Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Genetta genetta". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 555. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Larivière, S.; Calzada, J. (2001). "Genetta genetta" (PDF). Mammalian Species No. 680: 1–6. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2001)680<0001:GG>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Skinner, JD; Smithers, RHN (1990). The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. University of Pretoria. p. 472. ISBN 0869798022.

- ↑ Cuzin, F. (1996). "Répartition actuelle et statut des grands mammifères sauvages du Maroc (Primates, Carnivores, Artiodactyles)" (PDF). Mammalia. 60: 101. doi:10.1515/mamm.1996.60.1.101. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ↑ Pringle, J. A. (1977). "The Distribution of Mammals in Natal. Part 2: Carnivora". Annals of the Natal Museum. London: Adlard & Son. 23: 93–115.

- ↑ Stuart, C. T. (1981). "Notes on the Mammalian Carnivores of the Cape Province, South Africa" (PDF). Bontebok. Cape Town: Cape Dept. of Nature and Environmental Conservation. 1: 20–23. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ↑ Avenant, N. L. (1997). "Mammals recorded in the QwaQwa National Park (1994–1995)". Koedoe. Pretoria: South African National Parks. 40: 34. doi:10.4102/koedoe.v40i1.261.

- ↑ Morales, A. (1994). Earliest genets in Europe. Nature 370: 512–513.

- ↑ Gaubert, P., Jiguet, F., Bayle, P., & Angelici, F. M. (2008). Has the common genet (Genetta genetta) spread into south‐eastern France and Italy? Italian Journal of Zoology 75(1): 43–57.

- ↑ Zabala, J. and I. Zuberogoitia. (2010). Late summer-early winter reproduction in common genets, Genetta genetta. Mammalia 74: 89–91.

- 1 2 Camps, D. (2011). Resting site selection, characteristics and use by the common genet Genetta genetta (Linnaeus 1758). Mammalia 75 (1): 23–29.

- ↑ Galantinho, A., & Mira, A. (2009). "The Influence of Human, Livestock, and Ecological Features on the Occurrence of Genet (Genetta genetta): A Case Study on Mediterranean Farmland. Sakura-mura, Iboraki, Japan: Ecological Research (Ecological Society of Japan) 24: 671–685.

- ↑ Virgós, E.; Casanovas, J. G. (1997). "Habitat Selection of genet Genetta genetta in the Mountains of Central Spain". Acta Theriologica. Polish Scientific Publishers PWN. 42: 173–175.

- ↑ Ribas, A., Felui, C., and Casanova, J.C. (2009). Distribution of the cestode Taenia parva (Taeniidae) along the digestive tract of the common genet (Genetta genetta). Helminthologia 46, 1: 35–38.

- ↑ Camps D, Villero D, Ruiz-Olmo J, Brotons L. 2016. Mammalian Biology. Niche constraints to the northwards expansion of the common genet (Genetta genetta, Linnaeus 1758) in Europe

- ↑ Palomares, F.; Delibes, M. (1994). "Spatio-temporal ecology and behavior of European genets in southwestern Spain". Journal of Mammalogy. 75 (3): 714–724. doi:10.2307/1382521.

- ↑ Zuberogoitia, I., Zabala, J., Garin, I., & Aihartza, J. (2002). Home range size and habitat use of male common genets in the Urdaibai biosphere reserve, Northern Spain. Zeitschrift für Jagdwissenschaft 48(2): 107–113.

- ↑ Camps, D. (2008). Activity patterns of adult common genets Genetta genetta (Linnaeus, 1758) in Northeastern Spain. Galemys 20: 47–60.

- ↑ Camps, D. and Llobet, L. (2004). Space use of common genets Genetta genetta in a Mediterranean habitat of northeastern Spain: differences between sexes and seasons. Acta Theriologica 49: 491–502.

- ↑ Virgós, E.; Llorente, M. & Cortes, Y. (1999). "Geographical variation in genet (Genetta genetta L.) diet: a literature review". Mammal Review. 29 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.1999.00041.x.

- 1 2 Delibes, M. (1974). "Sobre alimentación y biología de la gineta (Genetta genetta L.) en España". Doñana: Acta Vertebrata. Seville: Estación Biológica de Doñana. 1.

- ↑ Pérez-Jiménez, J. M.; Soler-Cruz, M. D.; Benítez-Rodríguez, R.; Ruíz-Martínez, I.; Díaz-López, M.; Palomares-Fernández, F. & Delibes-de Castro, M. (1990). "Phthiraptera from some Wild Carnivores in Spain". Systematic Parasitology. 15 (2): 107–117. doi:10.1007/bf00009987.

- ↑ Delibes, M. and Gaubert, P. (2013). Genetta genetta Common Genet (Small-spotted Genet). In: J. Kingdon and M. Hoffmann (eds.) The Mammals of Africa. V. Carnivores, Pangolins, Equids and Rhinoceroses, pp. 223–229. Bloomsbury, London, UK.

- ↑ Roeder, J. J. (1979). La reproduction de la genette (G. genetta L.) en captivité. Mammalia 43(4): 531–542.

- ↑ Roeder, J. J., & Pallaud, B. (1980). Ontogenèse des comportements alimentaires et de prédation chez trois genettes (Genetta genetta L.) nées et élevées en captivité: rôle de la mère. Mammalia 44(2): 183–194.

- ↑ Delibes, M. (1999). Genetta genetta. In: A.J. Mitchell-Jones, G. Amori, W. Bogdanowicz, B. Kryštufek, P.J.H. Reijnders, F. Spitzenberger, M. Stubbe, J.B.M. Thissen, V. Vohralík and J. Zima (eds.) The Atlas of European Mammals, pp. 352–353. Academic Press, London, UK.

- ↑ Estes, R. (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Ewer, R. (1973). The Carnivores. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- ↑ Linnaeus, C. (1758). Viverra genetta. Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis 1 (10th ed.). Laurentius Salvius, Stockholm.

- ↑ Cuvier, F. G. (1825). La genette de Barbarie. Plate XLVII in F. G. Cuvier and E. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (eds.) Histoire naturelle des mammifères. Tome 5. Roret, Paris, France.

- ↑ Fischer, J. B. (1829). Viverra senegalensis. Synopsis Mammalium. Addenda, Emendanda Et Index. J. G. Cottae, Stuttgardtiae.

- ↑ Hemprich, W. F., Ehrenberg, C. G. (1832). Symbolae physicae, seu Icones et descriptiones corporum naturalium novorum aut minus cognitorum, quae ex itineribus per Libyam Ægytum, Nubiam, Dongalam, Syriam, Arabiam et Habessiniam. Volume I: Mammalia. Ex Officina academica, Berolini.

- ↑ Gaubert, P., Taylor, P. J., & Veron, G. (2005). Integrative taxonomy and phylogenetic systematics of the genets (Carnivora, Viverridae, Genetta): a new classification of the most speciose carnivoran genus in Africa. In: Huber, B. A., Sinclair, B. J., Lampe, K.-H. (eds.) African Biodiversity: Molecules, Organisms, Ecosystems. Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium of Tropical Biology, Museum König, Bonn. Springer. Pp. 371–383.

| Wikispecies has information related to: Genetta genetta |

External links

- Animal Diversity Web: Genetta genetta

- Funet: Genetta Cuvier, 1816

- African Wildlife Foundation: Genet