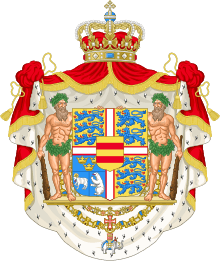

Christian IX of Denmark

Christian IX (8 April 1818 – 29 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 1863 to 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

Growing up as a prince of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, a junior branch of the House of Oldenburg which had ruled Denmark since 1448, Christian was originally not in the immediate line of succession to the Danish throne. However, in 1852, Christian was chosen as heir to the Danish monarchy in light of the expected extinction of the senior line of the House of Oldenburg. Upon the death of King Frederick VII of Denmark in 1863, Christian acceded to the throne as the first Danish monarch of the House of Glücksburg. [1]

The beginning of his reign was marked by the Danish defeat in the Second Schleswig War and the subsequent loss of the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg which made the king immensely unpopular. The following years of his reign were dominated by political disputes as Denmark had only become a constitutional monarchy in 1849 and the balance of power between the sovereign and parliament was still in dispute. In spite of his initial unpopularity and the many years of political strife, where the king was in conflict with large parts of the population, his popularity recovered towards the end of his reign, and he became a national icon due to the length of his reign and the high standards of personal morality with which he was identified.

Christian married his second cousin, Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel, in 1842. Their six children married into other royal families across Europe, earning him the sobriquet "the father-in-law of Europe". Most current European monarchs are descended from him, including Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, King Philippe of Belgium, King Harald V of Norway, King Felipe VI of Spain, and Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg. The British consort Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh is also an agnatic descendant of Christian IX, as are Michael I of Romania and Constantine II of Greece, whose thrones have been abolished. Also, the queens consort Anne of Romania, Anne-Marie of Greece, and Queen Sofia of Spain are among his descendants.[2]

Birth and family

Christian was born on 8 April 1818 at Gottorf Castle near the town of Schleswig in the Duchy of Schleswig as Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Beck, the fourth son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Beck, and Princess Louise Caroline of Hesse. He was named after Prince Christian of Denmark, the later King Christian VIII, who was also his godfather.[3]

Christian's father was the head of the ducal house of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Beck, a junior male branch of the House of Oldenburg. Through his father, Christian was thus a direct male-line descendant of King Christian III of Denmark and an (albeit junior) agnatic descendant of Helvig of Schauenburg (countess of Oldenburg), mother of King Christian I of Denmark, who was the "Semi-Salic" heiress of her brother Adolf of Schauenburg, last Schauenburg duke of Schleswig and count of Holstein. As such, Christian was eligible to succeed in the twin duchies of Schleswig-Holstein, but not first in line.

Christian's mother was a daughter of Landgrave Charles of Hesse, a Danish Field Marshal and Royal Governor of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, and his wife Princess Louise of Denmark, a daughter of Frederick V of Denmark. Through his mother, Christian was thus a great-grandson of Frederick V, great-great-grandson of George II of Great Britain and a descendant of several other monarchs, but had no direct claim to any European throne.

Early life

Initially, Christian lived with his parents and many siblings at Gottorf Castle, where the family stayed with Duke Friedrich Wilhelm's parents-in-law. However, on 6 June 1825, Duke Friedrich Wilhelm was appointed Duke of Glücksburg by his brother-in-law Frederick VI of Denmark, as the elder Glücksburg line had become extinct in 1779. He subsequently changed his title to Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg and founded the younger Glücksburg line. Subsequently, the family moved to Glücksburg Castle, where Christian was raised with his siblings under their father's supervision. Following the early death of the father in 1831, Christian grew up in Denmark and was educated in the Military Academy of Copenhagen.[4]

Marriage

As a young man, Christian unsuccessfully sought the hand of his third cousin, Queen Victoria, in marriage. At the Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen on 26 May 1842, he married his second cousin, Louise of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), a niece of Christian VIII.

Heir-presumptive to the throne

In 1853, with the approval of the great powers of Europe, Christian was chosen by King Frederick VII to be heir presumptive after the extinction of the most senior line to the Danish throne, as Frederick VII seemed incapable of fathering children. A justification for this choice was his marriage to Louise of Hesse-Kassel, who—as a niece of Christian VIII of Denmark—was a closer heir-presumptive to the throne than her husband.

How Christian became the heir-presumptive

Frederick VII's childlessness had presented a thorny dilemma and the question of succession to the Danish throne proved problematic. Denmark's adherence to the Salic Law and a burgeoning nationalism within the German-speaking parts of Schleswig-Holstein hindered all hopes of a peaceful solution. Proposed resolutions to keep the two Duchies together and part of Denmark proved unsatisfactory to both Danish and German interests. While Denmark had adopted the Salic Law, this only affected the descendants of Frederick III of Denmark, who was the first hereditary monarch of Denmark (before him, the kingdom was officially elective). Agnatic descent from Frederick III would end with the death of the childless King Frederick VII and his equally childless uncle, Prince Ferdinand. At that point, the law of succession promulgated by Frederick III provided for a Semi-Salic succession. There were, however, several ways to interpret to whom the crown could pass, since the provision was not entirely clear as to whether a claimant to the throne could be the closest female relative or not.

As the nations of Europe looked on, the numerous descendants of Helvig of Schauenburg began to vie for the Danish throne. Frederick VII belonged to the senior branch of Helvig's descendants. In 1863, Frederick, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg (1829–1880) (the future father-in-law of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany), proclaimed himself Frederick VIII of Schleswig-Holstein. Frederick of Augustenburg became the symbol of the nationalist German independence movement in Schleswig-Holstein after his father (in exchange for money) renounced his claims as first-in-line to inherit the twin-duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Following the London protocol of 8 May 1852, which concluded the First War of Schleswig, and given his father's renunciation, Frederick was deemed ineligible to inherit.

The closest female relatives of Frederick VII were his paternal aunt, Princess Louise Charlotte of Denmark, who had married a scion of the cadet branch of the House of Hesse, and her daughters. However, they were not agnatic descendants of the royal family, thus not eligible to succeed in Schleswig-Holstein.

The dynastic female heiress reckoned most eligible according to the original law of primogeniture of Frederick III was Caroline of Denmark (1793–1881), the childless eldest daughter of the late king Frederick VI. Along with another childless daughter, Wilhelmine of Denmark (1808–1891), Duchess of Glücksburg; the next heir was Louise, sister of Frederick VI, who had married the Duke of Augustenburg. The chief heir to that line was the selfsame Frederick of Augustenburg, but his turn would have come only after the death of two childless princesses who were very much alive in 1863.

The House of Glücksburg also held a significant interest in the succession to the throne. A more junior branch of the royal clan, they were also descendants of Frederick III through the daughter of King Frederick V of Denmark. Lastly, there was yet a more junior agnatic branch that was eligible to succeed in Schleswig-Holstein. There was Christian himself and his three older brothers, the eldest of whom, Karl, was childless, but the others had produced children, and male children at that.

Prince Christian had been a foster "grandson" of the "grandchildless" royal couple Frederick VI and his Queen consort Marie (Marie Sophie Friederike of Hesse). Familiar with the royal court and the traditions of the recent monarchs, their young ward Prince Christian was great-nephew of Queen Marie and descendant of a first cousin of Frederick VI. He was brought up as Danish, having lived in Danish-speaking lands of the royal dynasty and had not become a German nationalist, which made him a relatively good candidate from the Danish point of view. As junior agnatic descendant, he was eligible to inherit Schleswig-Holstein, but was not the first in line. As a descendant of Frederick III, he was eligible to succeed in Denmark, although here too, he was not first-in-line.

| Family of Christian IX of Denmark | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1842, Christian married Princess Louise of Hesse, daughter of the closest female relative of Frederick VII. Louise's mother and brother, and elder sister too, renounced their rights in favor of Louise and her husband. Prince Christian's wife was now the closest female heiress of Frederick VII.

In 1852, the thorny question of Denmark's succession was resolved by the London Protocol of 8 May 1852, through which Christian was chosen as next-in-line for the throne after Frederick VII and his uncle. The decision was implemented by the Danish Law of Succession of 31 July 1853—more precisely, the Royal Ordinance settling the Succession to the Crown on Prince Christian of Glücksburg[5]—which designated him as heir to the entire Danish monarchy following the extinction of the male line of Frederick III and granted him the title Prince of Denmark.

Succession and Second Schleswig War

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Upon the death of Frederick VII on 15 November 1863, Christian succeeded to the throne as Christian IX. Denmark was immediately plunged into a crisis over the possession and status of Schleswig and Holstein, two provinces to Denmark's south. In November 1863 Frederick of Augustenburg claimed the twin-duchies in succession after King Frederick. Under pressure, Christian signed the November Constitution, a treaty that made Schleswig part of Denmark. This resulted in the Second Schleswig War between Denmark and a Prussian/Austrian alliance in 1864. The Peace Conference broke up without having arrived at any conclusion; the outcome of the war was unfavorable to Denmark and led to the incorporation of Schleswig into Prussia in 1865. Holstein was likewise incorporated into Austria in 1865, then Prussia in 1866, following further conflict between Austria and Prussia.

Following the loss, Christian IX went behind the backs of the Danish government to contact the Prussians, offering that the whole of Denmark could join the German confederation, if Denmark could stay united with Schleswig and Holstein. This proposal was rejected by Bismarck, who feared that the ethnic strife in Schleswig between Danes and Germans would then stay unresolved. Christian IX's negotiations were not publicly known until published in the 2010 book Dommedag Als by Tom Buk-Swientys, who had been given access to the royal archives by Queen Margrethe II.[6]

Reign

The defeat of 1864 cast a shadow over Christian IX's rule for many years and his attitude to the Danish case—probably without reason—was claimed to be half-hearted. This unpopularity was worsened as he sought unsuccessfully to prevent the spread of democracy throughout Denmark by supporting the authoritarian and conservative prime minister Estrup, whose rule 1875–94 was by many seen as a semi-dictatorship. However, he signed a treaty in 1874 which allowed Iceland, then a Danish possession, to have its own constitution, albeit one that still had Denmark ruling Iceland. In 1901, he reluctantly asked Johan Henrik Deuntzer to form a government and this resulted in the formation of the Cabinet of Deuntzer. The cabinet consisted of members of the Venstre Reform Party and was the first Danish government not to include the conservative party Højre, even though Højre never had a majority of the seats in the Folketing. This was the beginning of the Danish tradition of parliamentarism and clearly bettered his reputation for his last years.

Another reform occurred in 1866, when the Danish constitution was revised so that Denmark's upper chamber would have more power than the lower. Social security also took a few steps forward during his reign. Old age pensions were introduced in 1891 and unemployment and family benefits were introduced in 1892.

Death and succession

Queen Louise died on 29 September 1898 at Bernstorff Palace near Copenhagen. Christian himself died peacefully of old age at 87 at the Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen after a reign of 42 years and 75 days. After lying in state at the chapel at Christiansborg Palace, he was interred beside Queen Louise in Christian IX's Chapel in Roskilde Cathedral, the traditional burial site for Danish monarchs since the 15th century.

He was succeeded as king by his eldest son, Frederick, who ascended the throne as King Frederick VIII.

Legacy

"Father-in-Law of Europe"

.jpg)

Christian's family links with Europe's royal families earned him the sobriquet "the father-in-law of Europe". Four of Christian's children sat on the thrones (either as monarchs or as consorts) of Denmark, the United Kingdom, Russia, and Greece.

His daughter Thyra could have become Queen of Hanover had her husband, Prince Ernest Augustus, not been deprived of the throne of Hanover upon its annexation by Prussia in 1866. His youngest son, Valdemar, was offered the crown of Bulgaria, but had to decline under international pressure.

The great dynastic success of the six children was to a great extent not attributable to Christian himself, but the result of the ambitions of his wife Louise of Hesse-Kassel. Some have compared her dynastical capabilities to those of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. An additional factor was that Denmark was not one of the Great Powers, so the other powers did not fear that the balance of power in Europe would be upset by a marriage of one of its royalty to another royal house.

Christian's grandsons included Nicholas II of Russia, Constantine I of Greece, George V of the United Kingdom, Christian X of Denmark and Haakon VII of Norway.

Today, most of Europe's reigning and ex-reigning royal families are direct descendants of Christian IX, and most current European monarchs are descended from him, including Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, King Philippe of Belgium, King Harald V of Norway, King Felipe VI of Spain and Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg. The consort Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and former consort Queen Sofía of Spain are also agnatic descendants of Christian IX, as is Constantine II, the former and last King of the Hellenes, and his consort the former Queen Anne-Marie. King Michael I of Romania and his wife Queen Anne of Romania are also descendants Christian IX.[7]

Issue

Ancestry

Titles, styles, honours and arms

| Styles of King Christian IX of Denmark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Majesty |

Titles and styles

- 8 April 1818 – 6 June 1825: His Serene Highness Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Beck

- 6 June 1825 – 31 July 1853: His Serene Highness Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg

- 31 July 1853 – 21 December 1858: His Highness Prince Christian of Denmark

- 21 December 1858 – 15 November 1863: His Royal Highness Prince Christian of Denmark

- 15 November 1863 – 29 January 1906: His Majesty The King of Denmark

His official full title was Christian IX, By the Grace of God, King of Denmark, of the Wends and of the Goths; Duke of Schleswig, Holstein, Stormarn, the Ditmarsh, Lauenburg and Oldenburg.

Honours

King Christian IX Land in Greenland is named after him.

Christian IX was the 1,007th Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Spain in 1864 and the 744th Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1865.

Danish honours

- 22 June 1843: Order of the Elephant

- 15 November 1863: Grand Commander of the Order of the Dannebrog

Foreign honours

-

Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (Spain; 1864)

Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (Spain; 1864) -

Knight of the Order of the Garter (United Kingdom; 1865)

Knight of the Order of the Garter (United Kingdom; 1865) -

Grand Cordon of the Legion of Honour

Grand Cordon of the Legion of Honour

Yüksek İmtiyaz Nişanı (Ottoman Empire, 1885)[8]

See also

References

- ↑ "Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg Royal Family". Monarchies of Europe. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ↑ "HM King Christian IX of Denmark". European Royal History. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Welcome To Schloss Glücksburg". Schloss Glücksburg. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ↑ "HM King Christian IX of Denmark". Henry Poole & Co. June 17, 2013. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ↑ Royal Ordinance settling the Succession to the Crown on Prince Christian of Glücksburg. from Hoelseth's Royal Corner. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ↑ Hemmeligt arkiv: Kongen tilbød Danmark til tyskerne efter 1864 18 August 2010 (politiken.dk)

- ↑ Hein Bruins. "Descendants of King Christian IX of Denmark". heinbruins.nl. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ↑ Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi: İ.DH. 957-75653, HR.TO.336-89

Other sources

- Aronson, Theo (2014) A Family of Kings: The descendants of Christian IX of Denmark (Thistle Publishing) ISBN 978-1910198124

- Beéche, Arturo E. (2014) APAPA: King Christian IX of Denmark and His Descendants (Eurohistory) ISBN 978-0985460341

Bibliography

- Bramsen, Bo (1993). Huset Glücksborg. Europas svigerfader og hans efterslægt. (in Danish) (2nd ed.). Copenhagen: Forum. ISBN 87-553-1843-6.

- Fabricius-Møller, Jes (2013). Dynastiet Glücksborg, en Danmarkshistorie (in Danish). Copenhagen: Gad. ISBN 9788712048411.

- Olden-Jørgensen, Sebastian (2003). Prinsessen og det hele kongerige. Christian IX og det glücksborgske kongehus (in Danish). Copenhagen: Gad. ISBN 8712040517.

- Scocozza, Benito (1997). Politikens bog om danske monarker (in Danish). Copenhagen: Politikens Forlag. ISBN 87-567-5772-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christian IX of Denmark. |

- The Danish Monarchy's official site

- Christian IX at the website of the Royal Danish Collection at Amalienborg Palace

-

"Christian IX.". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Christian IX.". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

| Christian IX Cadet branch of the House of Oldenburg Born: 8 April 1818 Died: 29 January 1906 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Frederick VII |

King of Denmark 1863–1906 |

Succeeded by Frederick VIII |

| Duke of Schleswig and Holstein 1863–1864 |

Titles mediatised | |

| Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg 1863–1864 |

Succeeded by William I | |