Chariton

Chariton of Aphrodisias (/ˈkæritən, -ɒn/; Greek: Χαρίτων Ἀφροδισεύς)[1] was the author of an ancient Greek novel probably titled Callirhoe (based on the subscription in the sole surviving manuscript), though it is regularly referred to as Chaereas and Callirhoe[2] (which more closely aligns with the title given at the head of the manuscript). Recent evidence of fragments of the text on papyri suggests that the novel may have been written in the mid 1st century AD, making it the oldest surviving complete ancient prose romance and the only one to make use of apparent historiographical features for background verisimilitude and structure, in conjunction with elements of Greek mythology, as Callirhoë is frequently compared to Aphrodite and Ariadne and Chaereas to numerous heroes, both implicitly and explicitly.[3] As the fiction takes place in the past, and historical figures interact with the plot, Callirhoe may be understood as the first historical novel; it was later imitated by Xenophon of Ephesus and Heliodorus of Emesa, among others.

Chariton's date

Nothing is securely known of Chariton beyond what he states in his novel, which introduces him as "Chariton of Aphrodisias, secretary of the rhetor Athenagoras". The name "Chariton", which means "man of graces", has been considered a pseudonym chosen to suit the romantic content of his writing, but both "Chariton" and "Athenagoras" occur as names on inscriptions from Aphrodisias.[4]

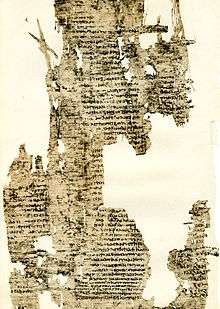

The latest possible date at which Chariton could have written is attested in papyri that contain fragments of his work, which can be dated by palaeography to about AD 200.[4] Analysis of Chariton's language has produced a range of proposals for dating. In the 19th century, before the discovery of the papyri, a date as late as the 6th century AD was proposed on stylistic grounds, while A. D. Papanikolaou argued in 1979 for the second half of the 1st century BC. One recent study of Chariton's vocabulary favours a date in the late 1st century or early 2nd century AD.[5]

Edmund Cueva has argued[3] that Chariton also depended on Plutarch's vita of Theseus for thematic material, or perhaps directly on one of Plutarch's sources, an obscure mythographer, Paion of Amathus. If the source is Plutarch, then a date after the first quarter of the 2nd century is indicated. There is a dismissive reference, however, to a work called Callirhoe in the Satires of Persius,[6] who died in AD 62; if this is Chariton's novel, then a relatively early date would be indicated.[4] Regardless, Chariton probably wrote before the other Greek novelists whose works survive,[7][8] making either his work or Petronius' Satyricon the earliest extant European novel.

Callirhoe

Chariton's novel exists in only one (somewhat unreliable) manuscript, from the 13th century. It was not published until the 18th century, and remained dismissed until the twentieth. It nevertheless gives insight into the development of ancient prose fiction.

Plot outline

The story is set against a historical background of ca 400 BC. In Syracuse, Chaereas falls madly in love with the supernaturally beautiful Callirhoe. She is the daughter of Hermocrates, a hero of the Peloponnesian War and the most important political figure of Syracuse, thus setting the narrative in time and social milieu. Her beauty (kallos) overawes crowds, like an earthly counterpart of Aphrodite's, as noted by Douglas Edwards.[9] They are married, but when her many disappointed suitors successfully conspire to trick Chaereas into thinking she is unfaithful, he kicks her so hard that she falls over as if dead.[10] There is a funeral, and she is shut up in a tomb, but then it turns out she was only in a coma, and wakes up in time to scare the pirates who have opened the tomb to rob it; they recover quickly and take her[11] to sell as a slave in Miletus, where her new master, Dionysius, falls in love with her and marries her, she being afraid to mention that she is already married (and pregnant by Chaereas). As a result, Dionysius believes Callirhoe's son to be his own.

Meanwhile Chaereas has heard she is alive, and has gone looking for her, but is himself captured and enslaved, and yet they both come to the attention of Artaxerxes, the Great King of Persia, who must decide who is her rightful husband, but is thinking about acquiring her for himself. When war erupts, Chaereas successfully storms the Persian stronghold of Tyre on behalf of the Egyptian rebels, and then wins a naval victory against the Persians, after which the lovers are finally reunited. Callirhoe writes to Dionysius, telling him to bring up her son and send him to Syracuse when he grows up. Chaereas and Callirhoe return in triumph to Syracuse, where Callirhoe offers prayers to Aphrodite, who has guided the events of the narrative.

Historical basis

Several characters from Callirhoe can be identified with figures from history, although their portrayal is not always historically accurate.[12][13] Hermocrates was a real Syracusan general, and did have a daughter (her name is unknown), who married Dionysius I of Syracuse. This Dionysius was tyrant of Syracuse from 405 to 367 BC and not a resident of Miletus. However, Callirhoe's expectation that her son will return to Syracuse after being brought up as Dionysius' own has been connected to the fact that the historical Dionysius I was succeeded in Syracuse by his son, Dionysius II.[13] The historical daughter of Hermocrates died after a violent attack by soldiers; that Callirhoe merely appears to be dead after being kicked by Chaereas has been seen as a deliberate change allowing Chariton "to resurrect her for adventures abroad".[14]

Chariton's Artaxerxes represents Artaxerxes II of Persia. Since Hermocrates died in 407 BC and Artaxerxes did not come to the throne until 404 BC, Chariton is anachronistic in having Hermocrates alive during Artaxerxes' reign. The hero Chaereas is not a historical figure, although his name recalls Chabrias, an Athenian general who fought in an Egyptian revolt against Persia in about 360 BC. His capture of Tyre may be based on that by Alexander the Great in 332 BC.[13]

Despite the liberties Chariton took with historical fact, he clearly aimed to place his story in a period well before his own lifetime. Tomas Hägg has argued that this choice of setting makes the work an important forerunner of the modern historical novel.[15]

Style and influences

There are echoes of Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, and other historical and biographical writers from the ancient world. The most frequent intertexts are the Homeric epics. The novel is told in a linear manner; after a brief first person introduction by Chariton, the narrator uses the third person. Much of the novel is told in direct speech, revealing the importance of oratory and rhetorical display (as in the presentation before the King of Persia) and perhaps as well the influence of New Comedy. Dramatic monologues are also used to reveal the conflicted states of the characters' emotions and fears (what should Callirhoe do, given that she is pregnant and alone?). The novel also has some amusing insights into ancient culture (for instance, the pirates decide to sell Callirhoe in Miletus rather than in the equally wealthy Athens, because they considered Athenians to be litigious busybodies who would ask too many questions).

The discovery of five separate fragments of Chariton's novel at Oxyrhynchus and Karanis in Egypt attest to the popularity of Callirhoe. One fragment, carefully written on expensive parchment, suggests that some, at least, of Chariton's public were members of local elites.[16]

See also

Other ancient Greek novelists:

- Xenophon of Ephesus, The Ephesian Tale

- Achilles Tatius, Leucippe and Clitophon

- Heliodorus of Emesa, The Aethiopica

- Longus, Daphnis and Chloe

Notes

- ↑ In literature, he is also known as Greek: Χαρίτων Ἀφροδισιεύς and Greek: Χαρίτων Ἀφροδίσιος.

- ↑ Greek: Τῶν περὶ Χαιρέαν καὶ Καλλιρρόην in Greek.

- 1 2 Edmund P. Cueva (Fall 1996). "Plutarch's Ariadne in Chariton's Chaereas and Callirhoe". American Journal of Philology. 117 (3): 473–484. doi:10.1353/ajp.1996.0045.

- 1 2 3 B. P. Reardon (2003) [1996]. "Chariton". In Gareth Schmeling (ed.). The Novel in the Ancient World (revised ed.). Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 309–335, pp. 312–317. ISBN 0-391-04134-7.

- ↑ Consuelo Ruiz-Montero (1991). "Aspects of the Vocabulary of Chariton of Aphrodisias". Classical Quarterly. 41 (2): 484–489. doi:10.1017/S0009838800004614.

- ↑ Persius (Aules Persius Flaccus). "Satire 1." Horace: Satires and Epistles; Persius: Satires. Trans. Niall Rudd. London: Penguin Classics, 2005. Print. In Satire 1 (lines 124-134), Persius suggests that those having a juvenile sense of humor and unsophisticated taste in art and literature should stick to "the law reports in the morning, and Calliroë after lunch."

- ↑ Ewen Bowie (2002). "The chronology of the earlier Greek novels since B.E. Perry: revisions and precisions". Ancient Narrative. 2: 47–63.

- ↑ S. Tilg (2010). Chariton of Aphrodisias and the Invention of the Greek Love Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957694-4.

- ↑ Douglas R. Edwards (Autumn 1994). "Defining the Web of Power in Asia Minor: The Novelist Chariton and His City Aphrodisias". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 62 (3): 699–718, p. 703. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lxii.3.699.

- ↑ The seeming-dead Callirhoe seems like Ariadne asleep on the shore at Naxos, Chariton says (1.6.2), and her second husband will be named for Dionysus.

- ↑ A parallel is in some versions of the myth of abandoned Ariadne.

- ↑ B. E. Perry (1930). "Chariton and His Romance from a Literary-Historical Point of View". American Journal of Philology. The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 51, No. 2. 51 (2): 93–134, pp. 100–104. doi:10.2307/289861. JSTOR 289861.

- 1 2 3 Reardon (1996), pp. 325–327.

- ↑ G. P. Goold (1995). Chariton: Callirhoe. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-674-99530-9.

- ↑ Tomas Hägg (1987). "Callirhoe and Parthenope: The Beginnings of the Historical Novel". Classical Antiquity. 6: 184–204. doi:10.2307/25010867. Reprinted in Simon Swain (ed.) (1999). Oxford Readings in the Greek Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 137–160. ISBN 978-0-19-872189-5.

- ↑ Edwards (1994), p. 700.

Further reading

Editions

- D'Orville, Jacques Philippe (1750). ΧΑΡΙΤΩΝΟΣ Αφροδισιέως τῶν περὶ ΧΑΙΡΕΑΝ καὶ ΚΑΛΛΙΡΡΟΗΝ ΕΡΩΤΙΚΩΝ ΔΙΗΓΗΜΑΤΩΝ ΛΟΓΟΙ Η (in Greek). Amsterdam: Apud Petrus Mortier. The first printed edition. With Latin translation by Johann Jacob Reiske.

- Hirschig, Wilhelm Adrian (1856). "Charitonis Aphrodisiensis De Chǣrea et Callirrhoe". Erotici Scriptores (PDF). Paris: Editore Ambrosio Firmin Didot. pp. 413–503. Retrieved 2007-02-16. With a reprint of Reiske's Latin translation.

- Hercher, Rudolf (1858–1859). Erotici Scriptores Graeci. Leipzig.

- Blake, Warren E. (1938). Charitonis Aphrodisiensis De Chaerea et Callirhoe Amatoriarum Narrationum libri octo. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Molinié, Georges (1989) [1979]. Chariton: Le Roman de Chairéas et Callirhoé. Collection des universités de France. revised by Alain Billault (2nd ed.). Paris: Belles Lettres. ISBN 2-251-00075-5. With French translation.

- Goold, G. P. (1995). Chariton: Callirhoe. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99530-9. With English translation.

- Reardon, Bryan P. (2004). De Callirhoe Narrationes Amatoriae Chariton Aphrodisiensis. Bibliotheca scriptorum Graecorum et Romanorum Teubneriana. K.G. Saur. ISBN 3-598-71277-4. Reviewed in BMCR

English translations

- Anonymous (1764). The Loves of Chǣreas and Callirrhoe. London: printed for T. Becket and P. A. De Hondt.

- Blake, Warren E. (1939). Chariton's Chaereas and Callirhoe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Reardon, Bryan P. (1989). "Chariton: Chǣreas and Callirhoe". In Bryan P. Reardon (ed.). Collected Ancient Greek Novels. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 17–124. ISBN 0-520-04306-5.

- Goold, G. P. (1995). Chariton: Callirhoe. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99530-9. With Greek text.

- Trzaskoma, Stephen M. (2010). Two Novels from Ancient Greece: Chariton's Callirhoe and Xenophon of Ephesos' An Ephesian Story. Indianapolis/Cambridge, MA: Hackett Publishing Company Inc. ISBN 978-1-60384-192-4.

Studies

- Perry, B. E. (1930). "Chariton and His Romance from a Literary-Historical Point of View". American Journal of Philology. The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 51, No. 2. 51 (2): 93–134. doi:10.2307/289861. JSTOR 289861.

- Helms, J., (1966) Character Portrayal in Chariton (Paris/The Hague:Mouton)

- Schmeling, Gareth L. (1974). Chariton. Twayne's world authors. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-2207-6.

- Reardon, B. P. (1982). "Theme, Structure and Narrative in Chariton". Yale Classical Studies. 27: 1–27. Reprinted in Simon Swain (ed.) (1999). Oxford Readings in the Greek Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 163–188. ISBN 978-0-19-872189-5.

- Hägg, Tomas (1987). "Callirhoe and Parthenope: The Beginnings of the Historical Novel". Classical Antiquity. 6: 184–204. doi:10.2307/25010867. Reprinted in Simon Swain (ed.) (1999). Oxford Readings in the Greek Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 137–160. ISBN 978-0-19-872189-5.

- James N. O'Sullivan, Xenophon of Ephesus, Berlin-New York 1995, pp. 145–170 (chapter on "Xenophon and Chariton").

- Smith, Steven D. (2007). Greek Identity and the Athenian Past in Chariton: The Romance of Empire. Ancient Narrative Supplementum 9. Groningen: Barkhuis & Groningen University Library. ISBN 978-90-77922-28-6. Reviewed in BMCR

- Tilg, Stefan (2010). Chariton of Aphrodisias and the Invention of the Greek Love Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957694-4. Reviewed in BMCR

External links

"Chariton". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Chariton". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.- Synopsis of the novel

- Tufts University – at the Perseus Project, Hercher's edition of the Greek text