Canvey Island

| Canvey Island | |

Canvey Island and the surrounding environment |

|

Aerial view from the south east of Canvey Island |

|

Canvey Island |

|

| Population | 38,170 (2011)[1] |

|---|---|

| – density |

|

| OS grid reference | TQ789829 |

| Civil parish | Canvey Island |

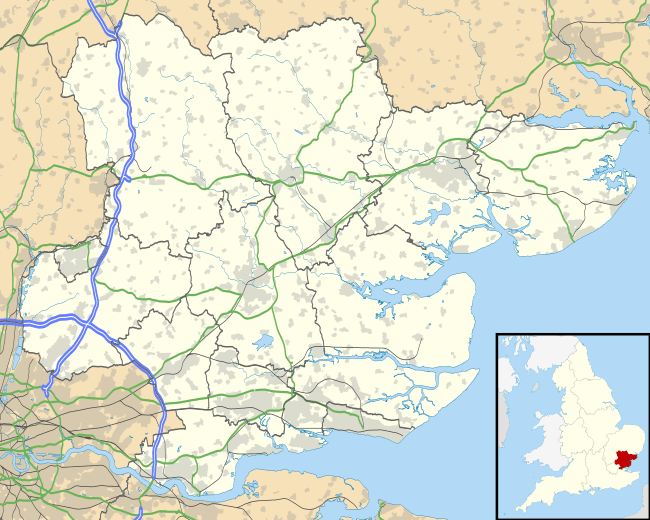

| District | Castle Point |

| Shire county | Essex |

| Region | East |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CANVEY ISLAND |

| Postcode district | SS8 |

| Dialling code | 01268 |

| 01374 | |

| Police | Essex |

| Fire | Essex |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| EU Parliament | East of England |

| UK Parliament | Castle Point |

| Website | www.canveyisland-tc.gov.uk |

Coordinates: 51°30′58″N 0°34′59″E / 51.516°N 0.583°E

Canvey Island is a civil parish and reclaimed island in the Thames estuary in Essex, England. It has an area of 7.12 square miles (18.44 km2) and a population of 38,170.[1] It is separated from the mainland of south Essex by a network of creeks. Lying only just above sea level it is prone to flooding at exceptional tides, but has nevertheless been inhabited since the Roman invasion of Britain.

The island was mainly agricultural land until the 20th century when it became the fastest growing seaside resort in Britain between 1911 and 1951. The North Sea flood of 1953 devastated the island, killing 58 islanders and leading to the temporary evacuation of the 13,000 residents.[3] Canvey is consequently protected by modern sea defences comprising 2 miles (3.2 km) of concrete sea walls.[4]

Canvey is also notable for its relationship to the petrochemical industry. The island was the site of the first delivery in the world of liquefied natural gas by container ship, and later became the subject of an influential assessment on the risks to a population living within the vicinity of petrochemical shipping and storage facilities.

History

Roman

Excavations on Canvey have unearthed a collection of early man-made objects comprising axes from the Neolithic era,[5] a bracelet dating from the Bronze Age,[6] and Iron Age pottery.[5] However, the remains of Roman structures and objects suggests the first settlement of Canvey occurred between 50 and 250 AD.[5][7] The remains point to a community existing with a farmstead, a garrison, a burial ground, and the operation of a large salt-making industry (revealed by the existence of several Red hills).[5][8]

The discovery of a Roman road found to terminate 109 yards (100 m) across the creek in neighbouring Benfleet suggests a means may have existed to facilitate the salt's distribution to Chelmsford and Colchester,[5] and the recovery of rich items of pottery and glassware of a variety only matched elsewhere by excavations of port facilities suggests the Romans may also have exploited Canvey's location in the Thames for shipping.[5][9]

Counus Island events

In 1607 the Elizabethan antiquarian William Camden noted in his work "Brittania" (a topographical and historical survey of all of Great Britain and Ireland) that Canvey Island (which he called Island Convennon) was documented in the 2nd century by the Alexandrian geographer Ptolemy.[10] In his work Geographia Ptolemy mentions a headland in the mouth of the Thames to the east of the Trinovantes region called Counus Island. However, the difficulties faced in determining the location of land areas in Ptolemy's ancient work have led modern researchers to question the correlation between Ptolemy's island and contemporary Canvey. MacBean and Johnson, 18th century historians contend Counus Island would have existed much further out to sea (or even likely to be the Isle of Sheppey[11]), so any similarity between the names is mere coincidence. Without any suitable island matching Ptolemy's Counus Island, 20th century historians White and Yearsley posit the documented island to have been lost or reduced to an insignificant sandbank by subsidence and the constant effects of the sea.[5][7]

Saxon and medieval

The settlement and agricultural development of Essex by the Saxons from the 5th century saw the introduction of sheep-farming which would dominate the island's industry until the 20th century. The Norman conquest saw the area of Canvey recorded in the Domesday Book as a sheep farming pasture under the control of nine villages and parishes situated in a belt across south inland and coastal Essex.[12] Apart from the meat and wool produced from the sheep, the milk from the ewes was used for cheese-making.[6] The abundance in later centuries would see the cheeses become a commodity taken for sale at the London markets, and at one stage exported via Calais to the continent.[5]

The existence of several place names on modern Canvey using the wick suffix (denoting the sheds in which the cheese was made) shows the influence of the early Saxon culture. Yearsley states the island has its name derived from the Anglo-Saxon Caningaege; meaning The Island of Cana's People.[5] The developments of the English language would lead to the more familiar name of Caneveye written in manorial records of 1254.[13] The period of development often produced a confused use of letters[14] such that comparative spellings would also include Canefe, Kaneweye, Kaneveye and Koneveye. By the 12th century, Essex and subsequently Canvey were in the possession of Henry de Essex who inherited the land from his grandfather, Swein, son of Robert fitz Wymarch.[15] During the reign of Henry II (1154–1189) the land was confiscated from de Essex and redistributed among the King's favoured nobles.[15]

Tudor divisions

Shown on John Norden's 1594 map with the second word "insula" with the traditional middle "s", facing the 'Isle' of Grain rather than a Latinised "Sheppey insula" to the southeast, is a close eastern division which is perhaps the part which later almost wholly merged into the present island, with a ditch being the current boundary, having the same far eastern points as the Canvey Point and Leighbeck Point marshes. Two Tree Island to the north is also recognisable, if halved in length.

The third eastern island or mudflat could well be the Counus i.e. "council" Island where the Trinovantes, Cantiaci and the Catuvellauni counselled with the Iceni, shortly before staging Boudicca's rebellion against the Romans.

If so Counus occupies an area from the Canvey Point Sand Bank until just before Shoeburyness, the eastern point of the relatively straight estuary so stretched the whole length of Southend on Sea, giving a reason for the tidal flats along this shore being so shallow (see for instance the world's longest pier which is in the town).

Cana's People were descendants of both Cantiaci and the Catuvellauni. If a boundary point, Counus would then be in tribal terms placed at the southern border of the Trinovantes on the eastern extent of the loose tribes also seen as the Tames (Thames).

14th century – 17th century

During Edward II's reign (1307–1327) the land was under the possession of John de Apeton[6] and the first attempts were made at managing the effects of the sea with rudimentary defences,[5][6] but periodical flooding continued to blight the small population of mostly shepherds and their fat-tailed variety of sheep for a further 300 years. William Camden wrote of the island in 1607 that it was so low that it was often quite flooded, except the hills, upon which the sheep have a place of safe refuge.[10] The uniform flatness of Canvey suggests that these hills are likely to be the red hills of the Roman salt making industry, or the early makeshift sea defences constructed by some of the landowners around their farms.

In 1622, Sir Henry Appleton (a descendant of John de Apeton), and Canvey's other landowners[17] instigated a project to reclaim the land and wall the island from the Thames. The scheme was managed by an acquaintance of Appleton's – Joas Croppenburg, a Dutch Haberdasher of Cheapside in London. An agreement was reached in 1623 which stipulated that in return for inning and recovering the island, the landowners would grant a third of the land as payment for the work.[6]

A relation of Croppenburg's, the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden present in England at the time of the project on a commission to drain the Fens and involved in repairing the seawall at Dagenham, has led to speculation that Vermuyden oversaw the project, but proof appears to be vague,[5] nevertheless the work was completed by around 300 Dutch skilled in the construction of dykes and other sea defences. The engineers successfully reclaimed 3,600 acres (15 km2)[5] by walling the island with local chalk, limestone and the heavy clay of the marshes, with the main length along the Thames faced with kentish ragstone.[5][7]

A broad drainage ditch was dug inland off the area facing the river while smaller inlets were filled in. Excess water would have collected in the broad ditch and then been discharged into the river by the means of seven sluices (later known as Commissioners Dykes).[7] The completion of the work saw a considerable number of the Dutch engineers take land as payment for their work, and consequently settle on the island.[15] Approximately one-third of Canvey's streets have names of Dutch origin.

Modern era

Chapman Lighthouse

The coast of Canvey Island was host to the Chapman Lighthouse as briefly described in Joseph Conrad's novel Heart of Darkness.[18] It is believed that the peril of the mudflats below such shallow waters off the Canvey Island coast prompted the Romans to devise some form of beacon as a warning in the area. In 1851 a hexagonal lighthouse was constructed by the engineer James Walker, a consultant lighthouse engineer at Trinity House at the time.[19] This all-iron lighthouse replaced a lightship which had been moored in the area for the preceding four years. The lighthouse was demolished in 1957 due to its poor condition.

Preventive service

Philip Benton reported about Canvey Chapel in 1867: "The seats are open and unappropriated, except one, which is set apart for the officer and the men under him of the Preventive Service; there being a station on the island for nine men, an officer and a chief boatman." The Preventive Men had their own special row of cottages close to the seafront near the old Lobster Smack Inn. That ancient pub was itself described by Charles Dickens in Great Expectations. So out of the way (and therefore the smugglers) was the inn behind the sea wall, in the 18th century it was known as 'The World's End'. In the 19th century, the isolation made it an ideal point for the meetings of pugilists. The row of Preventive Men's Cottages has survived against the odds. Today they are surrounded by a small housing estate.[20]

Bare-knuckle boxing

The Lobster Smack Inn saw many bare-knuckle fights in the 1850s, but few as dramatic as that between Tom 'the Brighton Boy' Sayers (1826–65) and Aaron Jones on 6 January 1857. The fight lasted for three hours and 65 rounds, and was finally declared a draw when it became too dark to see. Sayers won at the rematch a month later in London. Sometimes the bouts were between local families, the best known being that between champion Ben Court and Nat Langham. The fight arose from a family feud and Court took Langham to 60 rounds in September 1853. Langham was knocked down 59 times during the bout and due, it is said, to his sportsmanship Court agreed to settle their differences with a handshake.[21]

Canvey-on-sea

During the Victorian era Canvey became a very fashionable place to visit, and its air was promoted as having healing properties. This started in 1899, after the Black Monday floods, when an entrepreneur called Frederick Hester bought Leigh Beck Farm, and started what was to be called Southview Park estate.[22] The properties sold very quickly so Frederick bought more plots of land, selling them as dream homes for London's Eastenders. Hester wanted to create Canvey as a great seaside resort for Londoners, and so built the first promenade, a pier and a magnificent winter garden & palace, of which he planned to cover six miles (but only covered a mile), as well as a mono rail system (initially horse drawn then later electric).[22] Hester marketed Canvey as Ye Old Dutch Island giving many of the new roads Dutch sounding names, and enticing potential buyers with free rail tickets. The project started well with thousands of plots sold, however by 1905 the scheme had fallen apart due to materials not being delivered and issues with land ownership with the laying of the mono rail. Hester was declared bankrupt and everything was sold off at an auction held at Chimney's Farm.[22]

A new sea front was developed in the 1930s, with Canvey Casino - an amusement arcade and park opening as the first building on what would become Eastern Esplanade.[22] Since then further amusements, a cinema, the pioneering Labworth Cafe, the Monico pub and nightclubs such as the Goldmine were built. Canvey Island remained a popular holiday and weekend destination until the cheap foreign package holiday became popular in the 1970s.

Second World War

During the Second World War the island was a part of the GHQ Line, a line of concrete pillboxes constructed as a part of the defence against the expected German invasion. Some of the old pillboxes are still in place. Also, concrete barges were used extensively just off the south coast of the island, partly as a sea-barrier and also as a mounting point for anti-aircraft guns; one of which was beached on the east end of the island and remained for many years as a point of interest for visitors and a play area for many generations of the island's children. It has since been demolished by the Island Yacht Club as it was considered a risk to health and safety.

Along with the Coalhouse Fort at nearby East Tilbury, Thorney Bay on the southern coast of the island was the site of a degaussing station built to monitor the effectiveness of the equipment on board the allied ships passing along the Thames. The structure is the last intact degaussing station on the north side of the river, and was still operating in 1974. Known as the Canvey loop, the building was occupied by the Women's Royal Naval Service and used for monitoring merchant ships. The building has since been re-opened as a museum dubbed the "Bay Museum" and has First World War exhibits on the ground floor and Second World War exhibits on the first floor.[23][24]

Floods of 1953

On 1 February 1953, the infamous North Sea Flood hit the island during the night and caused the deaths of 58 people. Many of the victims were in the holiday bungalows of the eastern Newlands estate and perished as the water reached ceiling level.

The small village area of the island is approximately two feet (60 cm) above sea level and consequently escaped the effects of the flood. This included the Red Cow pub which was later renamed the King Canute in reference to the legend of the 11th century Danish king of England commanding the tide to halt with the sea lapping at his feet. The King Canute pub has (as of 18 May 2014) now been shut down and sold to an unknown developer.

After the flooding of 1953, a new seawall was built, which was then replaced with a significantly larger construction in the 1980s.

Petrochemical industry

The southern area of the Canvey Island West ward at Hole Haven has predominantly existed as petrochemical site since the first construction of an oil terminal there in 1936.[25] In 1959, as part of a pioneering Anglo-American project designed to assess the viability of transporting liquefied natural gas overseas, a gas terminal with two one thousand tonne capacity storage tanks was constructed at the site alongside the oil terminal. The gas terminal built by the British Gas Council was designed to store and distribute imported gas to the whole of Britain via the facilities at Thames Haven and the local refinery at Shellhaven in Coryton. The first delivery of 2,020 tonnes arrived on 20 February 1959 from Lake Charles, Louisiana by a specially modified liberty ship Normarti renamed The Methane Pioneer. The success of seven further deliveries over the following 14 months[26] established the international industry for transporting liquefied natural gas by sea,[27] but the discovery of oil and gas in North Sea limited further British development.

Planning permission was granted in the following years for Occidental Petroleum and the Italian oil company, United Refineries Ltd to develop a site further west for the construction of an oil refinery, but a report in 1975 by the Health and Safety Executive concluded that the residents of the island faced an unacceptable risk, which led to the permission being revoked.

The issue of risk was again highlighted in an attack by the IRA in January 1979 on a storage tank at the island's Texaco oil terminal. A bomb was detonated at a tank containing aviation fuel, but failed to ignite with the fuel escaping into a safety moat.[28][29] The Occidental site was abandoned in 1975 leaving a half-built oil refinery, storage tanks, and an unused mile long jetty which cost around £10 million of the approximate total of £60 million spent on the project.[30] However, in the following years the disused and undisturbed site flourished as a haven for wildlife, and in 2003, the final storage tanks were removed in a clean-up operation, and the site was renamed as Canvey Wick and opened as a nature reserve.

In September 1997, the celebrity steeplejack Fred Dibnah was hired by Safeway supermarkets to demolish the unused 450-foot (140 m) concrete chimney that was part of the abandoned oil refinery. Safeway had planned for the 2,500-ton chimney to be demolished on 18 September in front of a large crowd of invited guests. This would have been the first time Fred Dibnah's demolition technique of pit props and fire (without explosives) had been attempted on a concrete chimney and it was also the tallest chimney he had ever attempted to fell. However the chimney unexpectedly collapsed the previous day whilst Fred and his team were making the final preparations for the controlled demolition, fortunately without injury. The incident is described in detail in various biographies and by Fred himself in his public speaking events afterwards. Fred Dibnah later presented Safeway head office staff with brass paper weights (made from material salvaged from the chimney) stamped "The Great Canvey Island Chimney Disaster 1997".[31]

Geography

Canvey Island lies off the south coast of Essex 30 miles (48 km) east of London, and 15 miles (24 km) west of Southend-on-Sea. The island is separated from the mainland to the north and west by Benfleet, East Haven and Vange creeks, and faces the Thames Estuary to the east and south. Along with neighbouring Two Tree Island, Lower Horse and Upper Horse, Canvey is an alluvial island formed in the Holocene period from silt in the River Thames and material entering the estuary on the tides of the North Sea from the coast of Norfolk.[32][33] An unsuccessful search for coal beneath the island in 1953 revealed that the alluvium rests upon layers of London Clay, Lower London Tertiaries, Chalk, Lower Greensand and Gault Clay, with the basement rocks at a depth of 1,300 feet (400 m) consisting of hard Old Red Sandstone of Devonian age.[32][34]

The island is extremely flat, lying 10 feet (3 m) below mean high water level and consequently is at risk of flooding. Before reclamation, the surrounding area contained a number of islands separated by tidal creeks.[35] Flood defences have been constructed since the Middle Ages, and the first sea wall to completely surround the island was built as part of the island's reclamation in 1622.[36] The island suffered extensive flooding in 1731, 1736, 1791, 1881 and 1897, and substantial loss of life in the North Sea Flood of 1953.[37] As of 2008, the flood defences consisted of a concrete seawall, flood sirens and an internal surface storm water drainage system.

The extensive sea wall, completed in 1982, is 15 miles (24 km) long and surrounds 75% of the island's perimeter terminating with flood barriers spanning Benfleet Creek to the north and East Haven Creek in the west. The drainage system consists of sewers, culverts, natural and artificial dykes and lakes which feed seven pumping stations and gravity sluices that discharge the water into the Thames and creeks. Four of the discharge sites are "high flow" stations capable of discharging 600 litres of water per second at any tide level. The levels within the system are managed by a further five "low flow" pumping stations.[4] The Environment Agency's Thames Estuary 2100 flood defence plan includes Canvey Island as one site for alleviating the flood risks to London and the Thames estuary area. It is proposed that the western side of Canvey is developed as a site which is either temporarily flooded at times of risk, or transformed into a permanent wetland.[38][39]

Developments in the 20th century have produced a marked contrast between the environments in the east and west of the island. The eastern half of the island is allocated to residential areas, the main public amenities and a small holiday camp and seafront, while the western half of the island is mainly farmland, marshes and industrial areas. The marshes in the west include the 30 hectares known as West Canvey marshes, acquired by the RSPB in 2007,[40] and the Canvey Wick nature reserve. Canvey Wick is a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) at the site of the abandoned and incomplete oil refinery. The foundations of the 100 hectare (0.4 sq mile) site were prepared in the 1970s by laying thousands of tonnes of silt dredged from the Thames; the abandoned and undisturbed area has flourished as a haven for around 1,300 species of wildlife, many of which are endangered or were thought to be extinct; including the shrill carder bee, the emerald damselfly and the weevil hunting wasp.

It has been said that the site may have one of the highest levels of biodiversity in Western Europe.[41][42] Other areas of natural interest include the 20 acres (8 ha) of Canvey Lake Local Nature Reserve owned by Castle Point Borough Council. The lake was used for salt-making during the Roman settlement of the island, and is also thought to have functioned as an oyster bed.[43] At the eastern point of the island is the 36-acre (150,000 m2) Canvey Heights Country Park which was reclaimed from the Newlands landfill site that operated there between 1954–89. The park is the highest land elevation on the island and thus has wide views across the creeks and marshes and along the Thames. The environment supports an array of wildfowl such as skylarks, dark-bellied brent geese and grey plover.[44]

Governance

Canvey Island coalesced into a separate civil parish and ecclesiastical parish in 1881. These with separate remits replaced the 17 divisions of the land split largely into grazing meadowland since the Norman era by the neighbouring parishes of North Benfleet, South Benfleet, Bowers Gifford, Prittlewell, Southchurch, Hadleigh, Laindon, Pitsea and Vange.[33] In 1926, the parish was converted to the Canvey Island Urban District, then dissolved along with the Benfleet Urban District in the Local Government Act 1972 to form the local government district and borough of Castle Point.[33]

Since the 2010 General Election, the Member of Parliament representing the parliamentary constituency of Castle Point has been Rebecca Harris of the Conservative Party.

Canvey holds two seats on Essex County Council. As of 2009, the seat of Canvey Island West is represented by Ray Howard of the Conservative Party, while Canvey Island East is taken by Brian Wood (replaced in May 2013 by Dave Blackwell) of the Canvey Island Independent Party.[45]

| Affiliation | Councillors | |

| Canvey Island Independent Party (CIIP) | 16 | |

| Conservative Party | 1 | |

| Labour Party | 0 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 0 | |

Canvey is represented on Castle Point Borough Council by 17 councillors elected from six wards: Canvey Island Central, East, North, South, West and Winter Gardens. 16 of the 17 councillors belong to the Canvey Island Independent Party (CIIP) formed in 2003 by ex-Labour deputy Council leader and local resident Dave Blackwell. The remaining councillor is Conservative.[46]

The Canvey Island town council was formed in 2007 after a petition spearheaded by islander Albert Payne, with the signatures of 3,000 islanders, was accepted by the government.[47] As of 2008, the council has 11 councillors, 10 of whom are Canvey Island Independent members, and functions with Councillor surgeries and through four committees – Community Relations, Environment and Open Spaces, Planning and Policy and Finance. The surgeries are held at the town council offices, while the committees meet at various venues every fortnight.[48]

Demography

The population of Canvey has increased significantly in the last 100 years, mainly due to the island's popularity as a residential holiday resort during the first half of the 20th century, but also due to the London overspill plans and the introduction of council estates for 100 families from the Dagenham and Walthamstow boroughs in 1959.[49]

| Year | 1851 | 1887 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 2001 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 69[33] | 282[50] | 307[37] | 583[33] | 1,795[25] | 3,532[51] | 6,248[51] | 11,258[51] | 15,605[51] | 26,608[51] | 37,479[52] | 38,170[53] |

| Canvey Island Compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK census | Canvey Island | Castle Point | England |

| Total population | 37,479 | 86,608 | 49,138,831 |

| Foreign born | 4.2% | 4.6% | 9.2% |

| White | 98% | 97% | 91% |

| Asian | 0.6% | 0.7% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.2% | 0.2% | 2.3% |

| Christian | 74% | 75% | 72% |

| Muslim | 0.2% | 0.3% | 3.1% |

| Hindu | 0.1% | 0.2% | 1.1% |

| No religion | 16% | 15% | 15% |

| Over 65 years old | 15% | 17% | 16% |

| Unemployed | 2.2% | 2.4% | 3.3% |

At the 2001 UK census, the population of Canvey was 37,479 of which 87.9% of people were living within the five wards of the eastern area of the island at a population density of 38 persons per hectare, while the population density within the west ward – covering a larger area of the island – was 4.6 persons per hectare.

There were 15,312 dwellings on Canvey of which 98.7% were households. 42.4% were occupied by married couples, 13.9% of households contained three or more adults and no children, 26% were one person households and 8.1% were occupied by co-habiting couples. Canvey had a higher proportion at 35.2% of households owning their properties outright compared with the average of 29.2% for England, but had a lower proportion when compared to the average for Castle Point at 39.9%.

There was a higher proportion of female residents than male by 0.03%. The median age of the population was 40 years, and 23% were under 18, while 15% of residents were over 65.

The island has a high proportion of white people compared to national figures; the ethnicity recorded was 98.2% white compared with 91% for England. 0.6% of the population of Canvey were of a mixed ethnic group, while 0.6% were Asian, 0.2% Black and 0.2% Chinese.

4.2% of the population were foreign born, with 1.7% of residents born in another constituent country of the UK. 2.5% of the population were born outside the UK; and 1.2% of residents born outside Europe.

Religion was recorded as 74% Christian, 0.2% Muslim, 0.1% Jewish, 0.1% Hindu, while 16% of islanders had no religion.

The proportion of unemployed persons on Canvey was lower at 2.2% than for Castle Point at 2.4%, and England at 3.3%.[1]

Retail, leisure and industry

Canvey Island has several shopping areas. The main town centre known by older locals as the Haystack (after the pub in the town centre) is based around Furtherwick Road and the High Street. Most shops are located either in the Knightswick Centre (opened 1978) and Furtherwick Road with the lead store being Sainsbury's (formerly Key Markets). The other main store on Canvey is Morrisons which is located on Northwick Road, some way from the town centre. There are small shopping parades in St Michael's Road, The village on Long Road, Jones Corner on Long Road, Third Avenue, Point Road and dotted along the High Street. Castle Point Council are currently planning a £50m regeneration scheme for the town centre including building a larger Sainsbury's on the current Knightswick Car Park (with parking on the roof) and better connection to the town centre and the lake.[54]

Canvey currently has a small multi screen cinema located on the seafront called Movi-Starr (opened late 1990s) which replaced the former Rio Cinema which closed in the 1970s and was replaced by Rio Bingo Hall (Furtherwick Road). There are several arcades along this stretch of the seafront, along with a small amusement park and the Monico public house. The island had previously been known for its nightlife with both the Goldmine (hosted big name DJs including Emperor Rosko and Chris Hill) and King's Nightclubs (acts included comedian Mike Read)[55] being well known hot spots but these closed in the 1980s and 1990s respectively.

Canvey's industry is primarily based in two locations. The main location is Charfleet Industrial Estate, while there is further industrial buildings in Point Road. Canvey Island was home to Prout's Catermarans from 1949 to 2002.[56] Canvey is also home to a Calor Gas Storage Terminal, and an Oikos Oil depot located off Thames Road and Holehaven Road.[57]

Landmarks

The Lobster Smack public house at the southwest corner of the island is a grade II listed building dated to the 17th century. The pub was known to Charles Dickens who mentioned it in Great Expectations.[58] Alongside the pub is a row of wooden Coastguard cottages that date from the late 19th century which are also of grade II listed status.[59][60]

Landmarks from the era of Canvey's development as a seaside resort in the 20th century include the International style Labworth Café built 1932–33 and designed by Ove Arup. The building fell into a state of disrepair in the 1970s and 1980s but was renovated in 1996 and now functions as both a beach bistro and restaurant.

Opened in 1979, the Heritage Centre along Canvey Road is housed in the former St. Katherine's Church, which was built in 1874. Originally timber-framed, the church was rendered over in the 1930s to give it its present appearance; it closed as a place of worship in 1962. It now contains an art and craft centre with a small folk museum.

The island is also home to two Dutch Cottages, one in Haven Road and the other on Canvey Road, which were built during the 17th century by Dutch immigrants working on the sea walls. The cottage at Canvey Road is home to the Dutch Cottage museum.

Some photos of Canvey Island in Panoramio group "Canvey Island Photos"

Some of Canvey's lost landmarks include the Goldmine club on Western Esplanade,[61] the original Oysterfleet public house and lighthouse[62] and Cherry Stores.[63]

Transport

Road

Canvey Island is connected to the mainland in the northwest by two roads with bridges: the A130 (Canvey Way) and the B1014 (Canvey Road). Built in 1972, the A130 (Canvey Way) crosses East Haven Creek to Bowers Gifford and joins the London-Southend A13 at Sadler's Farm Roundabout. The two lanes of the A130 are currently the island's primary access route with 25,000 vehicles using the road and bridge per day.[64] The B1014 and Canvey Road Bridge (or Canvey Bridge) crosses Benfleet Creek to South Benfleet, and provides access to the c2c London (Fenchurch Street) to Shoeburyness line via Benfleet railway station.

Canvey Road Bridge was built in 1973, and replaced the island's first bridge to the mainland, which dated from 1931. The 91 metres (299 ft) Colvin Bridge – named after the Lord Lieutenant of Essex, Brigadier-General R.B. Colvin[65] – operated with a sliding 18 m (59 ft) central section that retracted for boats passing along Benfleet Creek.[33] Prior to the Colvin Bridge's construction, crossing the creek was achieved by either rowing-boat ferry or by a gravel causeway or stepping-stones at low tides.[37]

Congestion and the third road

Since the late 1970s, residents and local politicians have campaigned for the construction of a third access route (or "third road") to ease the island's congestion at rush hour and as a viable means of evacuation from flooding or industrial accidents at the petrochemical facilities.[66][67] In 2008, the congestion and failure to secure the construction of such a route or significant improvements has had the island at "breaking point" and on the verge of "civil unrest".[68] Plans for the third access route have included a tunnel to Kent,[69] and road bridges to places such as Leigh-on-Sea and Coryton.[70] Opposition to the route cite the enormous cost, the environmental damage, and the increase of vehicles to districts with already overburdened traffic systems.[69]

The island's access congestion was partially addressed by Essex Council in December 2011 with its completion of the £12.1 million Roscommon Way Extension.[71] The road runs from Northwick Road to Haven Road, providing a bypass for small numbers of traffic and adding a new entrance to Charfleet Industrial Estate while also remaining navigable in the case of flooding.[72] However, the road did not gain public support, and the extension has become known as 'The Road to Nowhere'.[73] This road is used by boy racers to do drifting in cars. As such, there are talks about putting speed restrictions in place such as road humps.

Bus and rail

Bus services have been running on Canvey since 1906.[37] From 1934, the services ran from the island's local bus depot at Leigh Beck by the Canvey & District Bus Co, later to be incorporated into the Eastern National Omnibus Company. The depot closed in 1978, but the building re-opened a year later as the Castle Point Transport Museum. The museum currently houses a collection of buses, commercial, military and emergency vehicles, and general items related to public road transport.[74] Organised by volunteers, the museum's annual show and open days coincide with a classic vehicle cruise that convenes at the car parks of the seafront.[75]

The current bus services on the island are operated by First Essex from the Hadleigh bus depot, and Regal Busways based in Chelmsford. First Essex is the main operator providing the island's internal services via the town centre, and provides services to places such as Southend, Basildon and Bournes Green.[76] Regal Busways began services on the island in May 2006, and operates the primary (1 and 1A) service to Chelmsford and services via South Benfleet, Battlesbridge, Howe Green and Sandon and occasionally beyond Chelmsford to Writtle.

Both bus companies provide services to Benfleet railway station, which is located close to Canvey Bridge, just north of the island. The railway station has a taxi rank. Train services are provided by c2c between London Fenchurch Street and Southend Central/Shoeburyness.

Education

Canvey Island has two comprehensive schools: the Cornelius Vermuyden School and Castle View School. Both were built in 2012 as replacements for the island's three ageing comprehensives, and as a response to the island's decreasing numbers of 11- to 16-year-olds.

Cornelius Vermuyden occupies the same site as its predecessor near Waterside Farm, while Castle View School – within the town centre and centre of the island – has replaced Furtherwick Park School, having previously existed within the island's north/central Winter Gardens Ward, overlooked by Hadleigh Castle. Furtherwick Park School shut in 2010, remaining pupils were then moved to Castle View School to finish their education. This site is now the location of Canvey Skills Campus which was built in 2013 and provides vocational education for 14- to 19-year-olds, and adult learning.[77]

Culture

Folklore

This island is just 5 miles from east to west and 3 miles north to south and has only been populated since the 17th century when the Dutch including reputedly Cornelius Vermuyden made the marshlands habitable. There are local legends of a Dutchman carrying a sack wandering the northern parts of the island. Although only inhabited since the 1600s, the land was used as grazing pastures by the Romans.[78]

Canvey has its own 'lady of the lake' in the form of a woman who was drowned there many years ago. Local stories are sketchy, some even say it was a man who drowned, but the majority speak of a female ghost who has wandered the area since her horse-drawn carriage plummeted into the lake. A recent clean-up of the lake found remains of two horses and fragments of a wooden carriage.

The story of 'The Black Man' and 'The White Lady' is believed to be a mythical tale conjured up by smugglers to stop people wandering onto the 'saltings' and finding their smuggled goods. It was said that 'The Black Man' offered a price for your soul, while the 'White Woman' would tempt you to dance with her. Men often spoke of trying to chase away the figures, only to watch them vanish before their eyes.[78]

Many night fishermen have reported seeing a tall, burly Viking standing on the mudflats at The Point, on the far eastern side of the island. It is believed that he was left behind by his fleet and waited for his ship to return; only to drown in the rising tide.[78]

A farm hand at the now long-demolished Knightswick Farm watched a nun approach the farm from the fields one afternoon from the porch of the farmhouse. Puzzled as to why the nun had walked across the muddy fields, the girl left the porch and walked towards the nun intending to greet her. Suddenly the nun began to vanish into the ground as she walked![78]

According to local legend a tunnel use to run from the Lobster Smack to Hadleigh Castle, and was said to be used by smugglers bringing in French wines.

Music

Canvey Island was an influential destination in the 1970s for artists of the Pub rock genre of music[79] such as Graham Parker, Elvis Costello,[80] Eddie and the Hot Rods, Nick Lowe,[81] and The Kursaal Flyers, while also being home to "Canvey Island's finest" band Dr. Feelgood.[82] The island continues to be a source of inspiration for artists such as British Sea Power who included a song entitled "Canvey Island" on their 2008 album Do You Like Rock Music?

Cultural references

Canvey Island is the setting for the British author Nicola Barker's 2002 novel Behindlings.[83] The island was also the subject of 2006 Turner Prize nominee Rebecca Warren's 2003 painted clay sculpture titled Canvey Island.[84]

Canvey was also home to a Prada fashion shoot in 2014 starring James McAvoy,[85] and featured in BBC's Silent Witness shown on 2 & 3 February 2015.[86]

Sport

Canvey Island has two senior semi-professional football teams in Canvey Island F.C. ('The Gulls') and Concord Rangers F.C. ('The Beachboys'). The oldest of the two clubs (founded in 1926) Canvey Island F.C. currently play a step lower than their newer rivals (Concord Rangers F.C. being founded in 1967) in the Isthmian League Premier Division, whilst 'The Beachboys' compete in The Conference South. Despite Canvey Island F.C. having historical success reaching the National League in 2004 and winners of the FA Trophy in 2001, it is Concord Rangers F.C. who boast the most impressive recent record; being the current holders of the Essex Senior Cup, having won the competition for the past 3 seasons.

Amateur participation in sport is popular on the island, with sports such as rugby union, cricket, and martial arts represented by clubs and corresponding facilities. The Castle Point Golf Course is situated on Canvey, and the Waterside Farm Sports Centre (recently refurbished 2013) provides members of Castle Point district with access to a swimming pool, an athletics track, general purpose sports halls, and a full size artificial surface football pitch. Also home to Canvey Island Swimming Club providing coaching for children ages 4 and upwards from beginners to competitive swimming through to National standard.

Water sport

Water sports are also popular recreational pursuits. Canvey has two sailing clubs in The Island Yacht Club and the Chapman Sands Sailing Club, with Benfleet Yacht Club and slipway also situated on the island at Benfleet Creek in the north. A region between Thorney bay and Labworth beach is designated by the Port of London Authority as an approved windsurfing area.[87] The Canvey Island Swimming Club provides lessons and training and is based at Waterside Farm Leisure Centre. The British record for the largest shore-caught angler fish (Lophius piscatorius) is from Canvey Island,[88] caught by H.Legerton in 1967. During 1953 and 1954 two unusual fish were washed up the shoreline and are known as Canvey Island Monster.

Notable people

- Ebenezer Joseph Mather, the founder of Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen spent his retirement on the island. He died 23 December 1927 and was buried in the grounds of the local St Nicholas church.[89] (Note here, Mather was buried in the grounds of The Parish Church – at the time this was St Katherine's Church. The grounds for St Nicolas had not been acquired.)

- Edwin Bernard Griffith MBE [90] Founded the Canvey Island Branch of the RNLI. In 1992 Griffith received an Honorary Life Governorship of the RNLI. He also received an award from the Lifesaving Society for saving the life of a boy off Canvey sea front. This award was given to the Canvey Island Heritage Centre and Museum following his death in June 2000.

- Clara James one of the founding members in 1889 of The Women's Trade Union Association (WTUA) established a holiday home on the island and served from 1925 as a parish councillor. She died on Canvey in 1956.[91]

- Jessica Judd, middle distance runner for UK Athletics, grew up on the island and was educated at Castle View [92][93]

- Dean Marney (footballer), a former St Katherine’s Primary School pupil, currently playis for Burnley F.C.[94][95]

- Roland and Francis Prout; the pioneers of the modern catamaran, were born and lived on the island and developed and operated the Prout Catamaran business from the boat yards at Leigh Beck. The brothers also represented Britain at the flatwater canoeing event at the 1952 Olympics.[96]

- Ashley George Old the war artist lived on Canvey from the mid-1960s until his death in 2001.[97]

- Dean Macey the Olympic decathlete was born and raised on the island

- Robert Denmark Olympic and Commonwealth (gold) 5,000 metres athlete attended Furtherwick Park School

- Peter Taylor the temporary manager of the England football team in 2000 was born on Canvey

- Frank Saul:FA Cup winner in 1967 with Tottenham Hotspur F.C. was born on Canvey.

- Ty Gooden: who played between 1992–2005 for teams such as Arsenal and Swindon Town F.C. , was sold in 2003 to non-league Canvey Island.

- Lee Brilleaux vocalist and founder of influential 1970s rhythm and blues group Dr. Feelgood moved to Canvey Island with his family when he was 13.

- Wilko Johnson guitarist best known for his work with Dr. Feelgood, also played with The Blockheads, The Wiilko Johnson Band and Roger Daltrey was born on Canvey

- Lew Lewis harmonica player with Eddie and the Hot Rods who later had his own group, and guested with The Stranglers and The Clash was brought up in the same Canvey Island street as Lee Brilleaux

- Joshua Hayward guitarist of The Horrors grew up in "a horrible island in the Thames Estuary called Canvey" before moving aged 18.[98]

See also

- Islands in the River Thames

- List of places on land with elevations below sea level

- Canvey Island Monster

Notes

- 1 2 3 Office for National Statistics. (2013). Statistics: Canvey Island.

- ↑ http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?newquery=*&newoffset=0&pageSize=25&edition=tcm%3A77-211059

- ↑ Canvey Island's 13,000 refugees. (1953-02-02). The Guardian, p. 1. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- 1 2 "Canvey Island Drainage scheme 2006". Environment agency. (May Avenue Pumping Station information board).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Yearsley, Ian. (2000). Islands of Essex. Canvey Island. Ian Henry Publications. ISBN 0-86025-509-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barsby. (1992).

- 1 2 3 4 White. (1994).

- ↑ see: The excavation of a Red Hill on Canvey Island. (Rodwell, 1966).

- ↑ Essex County Council Heritage Conservation. (2008). Romano-British Occupation of South Essex. Retrieved: 2008-03-27.

- 1 2 Camden 1586

- ↑ MacBean, & Johnson. (1773).

- ↑ Darby, (p. 157).

- ↑ Castle Point Borough Council. (2006). Local History: Canvey Island. Retrieved: 2008-02-27.

- ↑ English Place-Name Society. (1926).

- 1 2 3 Bills. (2004).

- ↑ The flood of January 1881 destroyed three miles (5 km) of the wall on the island's south side and subsequently this area was abandoned.

- ↑ Canvey's other landowners were Abigail Baker, Thomas Binckes, the Blackmore family, and Juilius Sludder. (Barsby, 1992).

- ↑ Joseph Conrad. (1899). The Heart of Darkness. (p. 5). Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87292-3.

- ↑ Cross-Rudkin & Chrimes 2008, pp. 813–815

- ↑ Robert Hallmann, "Essex History You Can See" (Tempus Publishing, 2006, ISBN 0 7524 3971 5)

- ↑ Carol Twinch, "Essential Essex" (The Breedon Books Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1-85983-729-0)

- 1 2 3 4 Islands of Essex by Ian Yearsley, Published 1994 by Ian Henry Books : ISBN 0 86025 508 5

- ↑ Matthew Stanton. (2008-05-05). Wartime museum. Castlepoint Yellow Advertiser. (p. 21).

- ↑ Canvey's World War II Degaussing Station. Canvey Island Community archive. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- 1 2 Stratton, 2000. (p. 192).

- ↑ Center for Energy Economics. (2008). Introduction to LNG: Brief History of LNG. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ Long and Gardner, 2004. (p. 293).

- ↑ The Secretary of State for the Home Department (Mr. Merlyn Rees) (18 January 1979). Commons Sitting – Bomb incidents. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ Sir Bernard Braine. (27 March 1979). Commons Sitting – Liquified gas storage (Canvey Island). Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ Canvey: Jetty scheme to prompt island jobs boom?. (1999-09-24). Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ "Fred Dibnah Remembered: The life and times of a Great Briton 1938–2004" Keith Langston, Mortons Media Group 2005, ISBN 9780954244262

- 1 2 The Geology of Essex. (2001). Essex RIGS Group. Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hallmann, Robert. (2006). Canvey Island, A History. Phillimore. ISBN 1-86077-436-9.

- ↑ Geology Site Account: Castle Point District, CANVEY ISLAND, Canvey Island Borehole, TQ82158330. (2008). The Essex Field Club. Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ↑ Rippon, Stephen (2011). "Panorama, The Journal of the Thurrock Local History Society". 50.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Maps showing successive stages in the reclamation are available at The South Essex Marshes

- 1 2 3 4 Dowd, D. M. (2008). Canvey Cyclopaedia. (RootsWeb.com). Retrieved: 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Steve Hackwell. (2008-09-15). Is it time to lose land to the sea?. Castle Point Echo. Newsquest.

- ↑ Steve Hackwell. (2008-09-19). You just can't use Canvey as an experiment with this flood scheme. Castle Point Echo. Newsquest. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. (2007-12-13). West Canvey Marshes. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ Castree, 2005. (p.2).

- ↑ Canvey Wick SSSI Designation by English Nature Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Canvey Lake. (2008). Greengrid. The Thames Gateway South Essex Partnership. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ "From Rubbish Tip to Country Park; Thames Gateway." The Times (London, England) (15 November 2005): 7. InfoTrac Full Text Newspaper Database. Gale. Essex Libraries. 28 August 2008

- ↑ Essex County Council Election Results. Essex County Council. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ Castle Point Borough Council. (2008). Councillors. Retrieved: 2008-05-31.

- ↑ Castle Point Borough Council. Canvey Island – Parish Council. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ Canvey Island Town Council. (2008). Annual report 2007/08.

- ↑ Canvey's New Neighbours Success Of £1M. Overspill Plan. (1959-06-04). (pg. 16; Issue 54478; col C). The Times.

- ↑ John Bartholomew. (1887). Gazetteer of the British Isles. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 A Vision of Britain through time: Island UD: Total Population. Department of Geography of the University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ↑ Office for National Statistics. (2008).

- ↑ Office for National Statistics. (2013).

- ↑ http://www.echo-news.co.uk/news/10217554.Developer_appointed_to_transform_Canvey_town_centre/

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IsZP1ESrqrIC&pg=PA407&lpg=PA407&dq=mike+read+at+kings+nightclub+canvey+island&source=bl&ots=4PglgQce2q&sig=hveB6yzJul8w9a7Dg4H43hHQYjw&hl=en&sa=X&ei=fgpKVPaqMNTV7AagvIDgDA&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=mike%20read%20at%20kings%20nightclub%20canvey%20island&f=false

- ↑ http://sailtoanywhere.blogspot.co.uk/2008/03/potted-history-of-prout-catamarans.html

- ↑ "Calor Gas delighted to unveil new road on Canvey Island". Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ Christopher Somerville. (2001-02-05). Essex: Walking on Canvey Island. The Telegraph. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ The Lobster Smack Public House. (2006). Listed Buildings Online. Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ 2–8 Haven Road. (2006). Listed Buildings Online. Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ "The 1970s The Goldmine Nightclub". Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Captain Gregson". Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "1930-2014 Cherry Stores RIP". Retrieved 9 Feb 2015.

- ↑ Canvey Way Improvement Plan. (2008). Essex County Council. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- ↑ Brigadier-General Colvin laid the bridge's first pile

- ↑ 3canvey – epetition response. (2008-04-28). Number10.gov.uk. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ↑ Canvey: Island in Prescott's £59 billion road plan. (2000-07-24). Evening Echo. Newsquest Media Group Ltd. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ↑ Canvey Gridlocked Following Crash, Canvey road petition backed. (2008-03-04). Evening Echo. Newsquest Media Group Ltd. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- 1 2 The £4bn Canvey-to-Kent tunnel. (2008-02-05). Evening Echo. Newsquest Media Group. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ↑ Canvey: New hope for access road. (1999-11-27). Thurrock Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. Retrieved 2009-01-12

- ↑ Essex County Council. (2012). Roscommon Way Extension Officially Open. Retrieved 2013-05-28.

- ↑ "Roscommon Way Planning Application – Supporting Statement" (PDF). 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- ↑ "OK for £27m plan to beat congestion at Canvey and Basildon". 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ↑ Moss, P. (2008). Castle point transport museum. Museum History. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ Transports of delight in the depot for 28 years. (2007-06-22). Evening Echo. Newsquest Media Group. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ↑ The First Essex services are the 21, 22 and 27.

- ↑ Essex County Council. (2013). Canvey Island Skills Centre, Canvey Island. Retrieved 2013-05-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Carmel King, "Haunted Essex" (The History Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-7524-5126-8,)

- ↑ Birch 2000

- ↑ The Elvis Costello Home Page. (2008). Don't Look Back: Credits. Retrieved: 2008-02-19.

- ↑ Andrew Shields and Peter Watts. (2007-08-07). The best of Essex: Culture: Canvey Island pub rock. Timeout. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ↑ The Elvis Costello Home Page. (2008). Liner Notes: Trust. Rhino liner notes. Retrieved: 2008-02-19.

- ↑ Peter Robins. Pond Theft – London Review of Books, Vol. 25 No. 2 · 23 January 2003. Retrieved: 2013-06-16.

- ↑ Canvey Community Archive. (2009). Turner Prize nominee Rebecca Warren's 2003 sculpture "Canvey Island". Retrieved: 2013-06-16

- ↑ http://www.echo-news.co.uk/news/11471660.Film_star_s_Prada_shoot___on_glam_Canvey/

- ↑ http://www.topix.com/forum/uk/canvey-island/T4389NNNB9AL4LQE2

- ↑ Port of London Authority. (2009). Vange Creek information board.

- ↑ British record fish committee

- ↑ Stephen Friend, 'Mather, Ebenezer Joseph (1849–1927)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 28 August 2008

- ↑ 1992 Birthday Honours,

- ↑ Gerry Holloway, 'James, Clara Grace (1866–1954)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, October 2007 accessed 28 August 2008

- ↑ "Interview with Jessica Judd - Eveing Echo 23/7/14". Retrieved 5 Nov 2014.

- ↑ "Interview with Jessica Judd - The Telegraph 11/7/13". Retrieved 5 Nov 2014.

- ↑ "Interview with Dean Marney's parents - Evening Echo 7/5/14". Retrieved 5 Nov 2014.

- ↑ "Scoop New on Spurs website - Dean Marney to play for ROI - 21/1/2005". Retrieved 5 Nov 2014.

- ↑ Ron Norman. (2008) G. Prout & Sons... and the Catamaran. Shearwater Association. Retrieved: 2008-02-22.

- ↑ http://www.canveyisland.org/page/ashley_george_old

- ↑ Kharas, Kev (7 May 2009). "The Horrors Daub Their Name In Brit Pop Tradition With Primary Colours". The Quietus.

References

|

|

|

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canvey Island. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Canvey Island. |

- Canvey History – Photographic Archives, Memories and Stories about the history of Canvey Island

- The Canvey Community Archive website

- The Canvey Community Archive website (the retired archive)

- Images of Roman period pottery recovered from Canvey

- Paul Smyth's contemporary watercolour paintings of Canvey Island from 1913 to 1952

- Buglife's Canvey Island project

- Canvey Wick Nature Reserve

- Charts of Benfleet Creek

- Panoramio group " Canvey Island Photos"

| Next island upstream | River Thames | Next island downstream |

| Lower Horse Island | Canvey Island | Two Tree Island |