Burgher people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 37,061 (2012 census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Province | |

| 24,170 | |

| 4,458 | |

| 3,347 | |

| 2,192 | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Burgher people, also known simply as Burghers, are a Eurasian ethnic group in Sri Lanka descended from Portuguese, Dutch, British[2][3] and other Europeans who settled in the island.[4][5] Portuguese and Dutch had held the maritime provinces of the island for centuries before the advent of the British Empire.[6][7][8] With the establishment of Ceylon as a crown colony, most of those who retained close ties with the Netherlands departed. However, a significant community of Burghers remained and largely adopted the English language.[7] During the nineteenth century they occupied a highly important place in Sri Lankan social and economic life.[8]

Portuguese settlers on Ceylon were essentially traders, but wished to form colonies, and Lisbon did nothing to discourage European settlement—even to the extent of advocating intermarriage with the Sinhalese. It was not the policy of the Dutch East India Company to endorse similar unions, although a number of unofficial liaisons between its employees and local women occurred in the late eighteenth century.[7]

Burghers may vary from generation to generation in physical characteristics; some intermarried with the British[8] and produced descendants with predominantly European phenotypes, including fair skin and a heavier physique, while others were almost indistinguishable from Sinhalese or Tamils.[6] Most Burgher people have preserved Western customs; especially among those of Portuguese ancestry their European religion, language, and surnames are retained with pride.[9][10]

Demographics

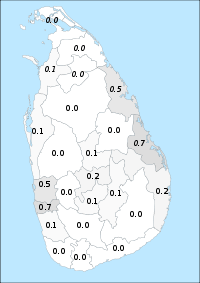

In the census of 1981, the Burgher population of Sri Lanka was 39,374 persons, about 0.2% of the total population. The highest concentration of Burghers is in Colombo (0.72%) and Gampaha (0.5%). There are also significant communities in Trincomalee and Batticaloa, with an estimated population of 20,000.

Burgher descendants are spread throughout the world. Families with surnames such as Foenandes (a variation of the Portuguese Fernandes), Mirano and Van Dort are of Dutch ancestry.

Legal definition

The Burghers were legally defined in 1883 by the Chief Justice of Ceylon, Sir Richard Ottley, given before the Commission, appointed in connection with the establishment of a legislative council in Ceylon. Burghers were defined as those whose father was born in Sri Lanka, with at least one European ancestor on one's direct paternal side, regardless of the ethnic origin of one's mother, or what other ethnic groups may be found on the father's side. Because of this definition, Burghers almost always have European surnames (mostly of Portuguese, Dutch and British origin, but sometimes German, French or Russian).[12]

History

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1881 | 17,900 | — |

| 1891 | 21,200 | +18.4% |

| 1901 | 23,500 | +10.8% |

| 1911 | 26,700 | +13.6% |

| 1921 | 29,400 | +10.1% |

| 1931 | 32,300 | +9.9% |

| 1946 | 41,900 | +29.7% |

| 1953 | 46,000 | +9.8% |

| 1963 | 45,900 | −0.2% |

| 1971 | 45,400 | −1.1% |

| 1981 | 39,400 | −13.2% |

| 1989 (est.) | 42,000 | +6.6% |

| 2001 | 35,300 | −16.0% |

| 2011 | 37,061 | +5.0% |

| Source:Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka[13] Data is based on the Sri Lankan Government Census. | ||

The Portuguese arrived in 1505 in what outsiders then called Ceylon. Since there were no women in the Portuguese navy, the Portuguese sailors married local Sinhalese and Tamil women. This practice was encouraged by the Portuguese.

The Dutch first made contact and signed a trade agreement with the Kingdom of Kandy in 1602. From 1640 on the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had a governor installed and conquered more and more fords from the Portuguese, until, in 1658, the last Portuguese were expelled. However, they permitted a few stateless persons of Portuguese-Jewish (Marrano) descent, and of mixed Portuguese-Sinhalese ancestry to stay. Many people having a Portuguese name were a result of forced conversions of local/native people in order to work for the Portuguese. As a result, Burghers with Portuguese names are most likely to be of Sinhalese ancestry, with a very small portion being Portuguese or mixed Portuguese-Sinhalese ancestry. Those of a Portuguese-Jewish background can be traced in various forms or surmised from their surname. Most Burghers of Eurasian descent with Portuguese surnames are of Sinhalese and Dutch, British, German, Swedish, and/or other European descent.

During the Dutch period, all Dutch colonial operations were overseen by the VOC ('Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie' or United East India Company). Virtually all Burghers from this period were employees of the VOC. The VOC employed not only Dutch nationals, but also enlisted men from the Southern Netherlands, the German states, Sweden, Denmark and Austria. It is therefore not unusual to find ancestors from these countries in many Dutch Burgher family trees.

The term 'Burgher' comes from the Dutch word burger, meaning "citizen" or "town dweller", and is cognate with the French and English word "bourgeois". At this time in Europe, there had emerged a middle class, consisting of people who were neither aristocrats nor serfs. These were the traders and businessmen, who lived in towns and were considered free citizens. In Europe, they were called burghers, and they were encouraged to migrate to the colonies in order to expand business horizons.

Dutch Ceylon had two classes of people of European descent: those who were paid by the VOC and were referred to as Company servants (i.e. employees), and those who had migrated of their own free will. The latter were not referred to as burghers in Ceylon, but rather by their rank, position or standing.

During British colonial rule, they were referred to by the British as 'Dutch Burghers' and formed the European-descended civilian population in Ceylon. To some degree the term of Burgher was used in a derogatory way to divide and conquer the population, as it distinguished between British and other races or positions. The 'Dutch Burgher' community took pride in its own achievements and prized their European ancestry. A number of Dutch Burgher Union journals have been created over a period of time, to record family histories. They were not only of Dutch origin but incorporated European (Dutch, German, Hungarian, Italian, French, Swedish etc.), United Kingdom, Portuguese Mix, and Sinhalese lines.

When the British took over in 1796, many VOC employees chose to leave. However, a significant number chose to stay, mostly those of mixed descent. Some chose to go to Batavia, which was the headquarters of the VOC. Reportedly about 900 families, both free citizens and United East India Company employees, decided to remain in Ceylon. The British referred to them all as 'Dutch Burghers'. One condition of their being allowed to stay was that they had to sign a Treaty of Capitulation to the British. Many 'Dutch Burghers' can find their ancestors' names in this treaty. At the time of the British conquest, the 900 'Dutch Burgher' families residing in Ceylon were concentrated in Colombo, Galle, Matara and Jaffna.

The Burghers included members of the Swiss de Meuron Regiment, a mercenary unit employed by the VOC. In diplomatic negotiations in Europe, Count de Meuron pledged allegiance to the British in exchange for back pay and information. This allowed the British to get detailed fortification information and reduce the fighting strength of Ceylon prior to 1796. The de Meuron Regiment refused to fight the Dutch due to relationships forged on the island of Ceylon and South Africa. Post 1796 members of the de Meuron Regiment stayed in Ceylon, whilst the regiment itself went off to fight and distinguish itself in India and later in Canada.

Culture

Until the early 20th century, many Burghers spoke English and a form of Portuguese Creole, even those of Dutch descent. Portuguese Creole had been the language of trade and communication with indigenous peoples. It is now only spoken in parts of the coastal towns of Trincomalee and Batticaloa. While much vocabulary is from Portuguese, its grammar is based on that of Tamil and Sinhalese.

Burgher culture is a rich mixture of East and West, reflecting their ancestry. They are the most Westernised of the ethnic groups in Sri Lanka. Most of them wear Western clothing, although it is not uncommon for a man to be seen wearing a sarong, or for a woman to wear a sari.

A number of elements in Burgher culture have become part of the cultures of other ethnic groups in Sri Lanka. For example, baila music, which has its origin in the music of 16th-century Portugal, has found its way into mainstream popular Sinhalese music. Lacemaking, which began as a domestic pastime of Burgher women, is now a part of Sinhalese culture too. Even certain foods, such as love cake, bol fiado (layered cake), ijzer koekjes, frikkadels (savoury meatballs) and lamprais, have become an integral part of Sri Lankan national cuisine.

Burghers are not physically homogeneous. It is possible to have a blond, fair-skinned Burgher, as well as a Burgher with a very dark complexion and black hair, a Burgher with complexion from brown to light brown and black hair, and a Burgher with fair complexion and black hair. Fair-skinned and dark-skinned children can even appear as brother and sister in the same family of the same parents. Burghers share a common culture rather than a common ethnicity. While some of the older generations of Burghers tried to dismiss the obvious Asian side of their ancestry, many younger Burghers today highly value this variety in their heritage.

Burghers have a very strong interest in their family histories. Many old Burgher families kept stamboeken (from the Dutch for "clan books"). These recorded not only dates of births, marriages and deaths, but also significant events in the history of a family, such as details of moving house, illnesses, school records, and even major family disputes. An extensive, multi-volume stamboek of many family lineages is kept by the Dutch Burgher Union.

Individual families often have traditions reflecting their specific family origins. Burghers of Dutch origin sometimes celebrate the Feast of Saint Nicholas in December, and those of Portuguese-Jewish origin observe customs such as the separation time of a woman after childbirth (see Leviticus 12:2-5), the redemption of the Firstborn (Pidyon ha-Ben), and the purification bath (taharah) after a daughter’s first period (see niddah). Most of the latter Burgher families, being unaware of the Jewish origins of these customs, have given them a Catholic slant. (Catholic and Episcopal churches had services for the churching of women after childbirth from ancient times.)

However, some traditions attributed to Judaism can also be explained as borrowings or retention from the Tamil and Sinhalese communities with whom many Burgher families also share ancestry and culture. For example, the purification bath after a girl’s first period is a common cultural feature of the Tamil and Sinhalese communities of Sri Lanka and neighboring India. Hence its prevalence amongst some Burghers families of Sri Lanka is not necessarily of Jewish origins.

Some commentators believe that the Burghers’ own mixed backgrounds have made their culture more tolerant and open. While inter-communal strife has been a feature of modern Sri Lankan life, some Burghers have worked to maintain good relations with other ethnic groups. However, prejudices within the community as a result of a condescending attitude outside of it, have caused some migrant Burghers to take on the traditions of the country in which they reside and disconnect from the ties to their country afterwords.

In 2001 the Burghers established a heritage association, the Burgher Association, with headquarters at No.393, Union Place, Colombo 2 Sri Lanka.

Notable Burghers

See also

References

- ↑ "A2: Population by ethnic group according to districts, 2012" (PDF). Census of Population & Housing, 2011. Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka. 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ Peter Reeves, ed. (2014). The Encyclopedia of the Sri Lankan Diaspora. Editions Didier Millet. p. 28. ISBN 978-981-4260-83-1. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Sarwal, Amit (2015). Labels and Locations: Gender, Family, Class and Caste – The Short Narratives of South Asian Diaspora in Australia. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-1-4438-7582-0. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Jupp, James (2001). The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 940. ISBN 978-0-521-80789-0.

- ↑ Ferdinands, Rodney (1995). Proud & Prejudiced: the story of the Burghers of Sri Lanka (PDF). Melbourne: R. Ferdinands. pp. 2–32. ISBN 0-646-25592-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015.

- 1 2 Orizio, Riccardo (2000). "Sri Lanka: Dutch Burghers of Ceylon". Lost White Tribes: The End of Privilege and the Last Colonials in Sri Lanka, Jamaica, Brazil, Haiti, Namibia, and Guadeloupe. Simon and Schuster. pp. 5–55. ISBN 978-0-7432-1197-0. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 Pakeman, SA. Nations of the Modern World: Ceylon (1964 ed.). Frederick A Praeger. pp. 18–19. ASIN B0000CM2VW.

- 1 2 3 Cook, Elsie K (1953). Ceylon - Its Geography, Its Resources and Its People. London: Macmillan & Company Ltd 1953. pp 272—274.

- ↑ Smith, IR. Sri Lanka Portuguese Creole Phonology. 1978. Dravidian Linguistics Association.

- ↑ de Silva Jayasuriya, Shihan (December 1998). "The Portuguese Cultural Imprint on Sri Lanka" (PDF). Lusotopie 2000. pp. 253–259. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Department of Census and Statistics-Sri Lanka".

- ↑ Mülle, J.B. "One Nation: diversity and multiculturalism-Part I". The Island (Sri Lanka). Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ↑ "Population by ethnic group, census years" (PDF). Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

Bibliography

- Bosma, Ulbe; Raben, Remco (2008). "Separation and Fusion". Being "Dutch" in the Indies: A History of Creolisation and Empire, 1500-1920. NUS Press. pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-9971-69-373-2. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burgher people. |

- The Dutch Burghers of Sri Lanka, Dutch Ceylon

- The Burgher Association

- Burgher Association of Australia

- Burgher Association of UK