Bruchweiler

| Bruchweiler | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Bruchweiler | ||

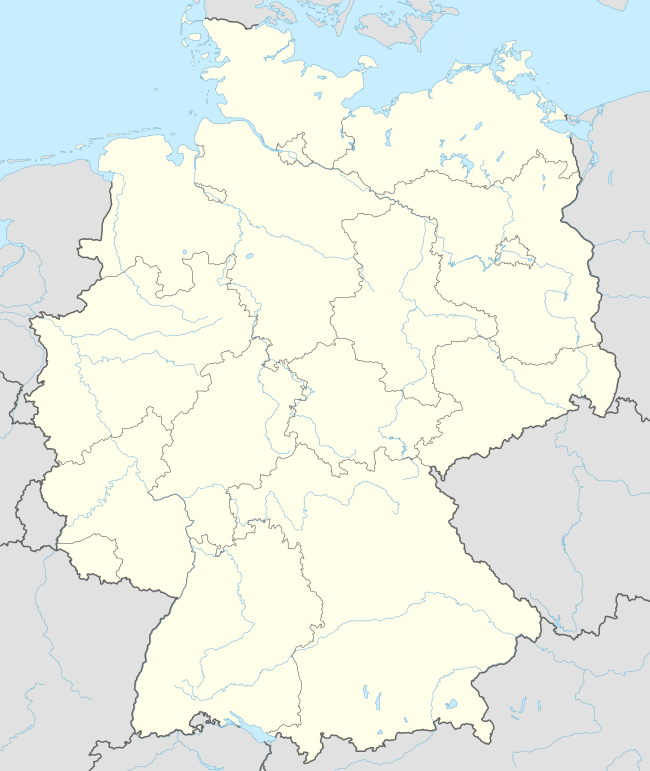

Location of Bruchweiler within Birkenfeld district  | ||

| Coordinates: 49°47′53″N 7°13′26″E / 49.798°N 7.224°ECoordinates: 49°47′53″N 7°13′26″E / 49.798°N 7.224°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| District | Birkenfeld | |

| Municipal assoc. | Herrstein | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Horst Scherer | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 8.13 km2 (3.14 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 502 | |

| • Density | 62/km2 (160/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 55758 | |

| Dialling codes | 06786 | |

| Vehicle registration | BIR | |

| Website | www.bruchweiler.de | |

Bruchweiler is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Birkenfeld district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde of Herrstein, whose seat is in the like-named municipality.

Geography

Location

The municipality lies on the south slope of the Steingerüttelkopf, which at 756 m above sea level is one of the highest peaks in the Hunsrück. Much of the local countryside is wooded, and Bruchweiler’s elevation of 555 m above sea level makes it one of Rhineland-Palatinate’s highest municipalities. Bruchweiler also lies on the Deutsche Edelsteinstraße (“German Gem Road”).

Climate

Yearly precipitation in Bruchweiler amounts to 831 mm, which is rather high, falling into the highest third of the precipitation chart for all Germany. At 69% of the German Weather Service’s weather stations, lower figures are recorded. The driest month is April. The most rainfall comes in December. In that month, precipitation is 1.4 times what it is in April. Precipitation varies only slightly, with rainfall quite evenly spread over the whole year.

History

About 500 BC, the Treveri, a people of mixed Celtic and Germanic stock, from whom the Latin name for the city of Trier, Augusta Treverorum, is also derived, settled here. Their area of settlement was framed by the rivers Ahr, Rhine and Nahe. All indications are that it was these Treveri who built the ringwalls at the Wildenburg as a refuge castle when, in the last century before the Christian Era, they were beset first by Germanic tribes and then later by the Romans, who under Julius Caesar’s leadership enjoyed a number of successes that led to Roman hegemony throughout the Treveri’s homeland. It became the Roman province of Belgica, whose boundary ran from somewhere near the Stumpfer Turm, where the important Celtic-Roman centre of Belginum lay, southwards to the ridge of the Idar Forest, along the ridge for a way before turning southwards again somewhere between Sensweiler and Wirschweiler, whence it ran to the Idarbach, crossed it by way of the Ringkopf, then running down the Siesbach to the river Nahe. While the lands west of this line formed Belgica, the lands to the east, including Bruchweiler, belonged to the Roman province of Germania Superior, whose capital was at Mogontiacum (Mainz). In later centuries, the border alignment mentioned above became the boundary between the Nahegau and the Moselgau (a territory that stretched along the Moselle), and after the 843 Treaty of Verdun, the boundary between Middle Francia and East Francia, two of the three entities into which Charlemagne’s old empire was split by that treaty.

Roman rule lasted 450 years in the Bruchweiler area. Interesting archaeological finds were made within Bruchweiler’s limits in 1922, and again in 1947 and 1948. All together, six cist graves, each measuring some 50 ×50 cm, with grave goods, were unearthed, dating from the late 2nd or 3rd century. In 1885, a trove of 26 coins was found on the Wildenburg Heights, among them some with Emperor Maximinus Thrax’s (ruled 235-238) effigy. Even earlier, in 1839, on the terracelike area southwest of the forester’s house, a Roman bath complex had been dug up, leading to the conclusion that there must have been a Roman settlement there.

In Late Roman times, about AD 350, a watch and signalling station may have been built by the Romans on the high quartzite cliffs with their broad view over the countryside to guard against Germanic incursions. In the 5th century, Roman hegemony was destroyed by the Franks, who were thrusting into the area from the east. Little is known about Frankish times in the Bruchweiler area, although placenames nearby ending in —rath, —roth, —rodt or —ert are undoubtedly Frankish foundings, referring as they do to the Franks’ customary practice when settling new land, namely clearing the woods (German still uses the verb roden to mean “clear”). The Franks were also instrumental in the introduction of Christianity into the area. When Charlemagne introduced the Gau system, Bruchweiler found itself in the Nahegau. Heading the Gau was a Gaugraf (“Gau Count”), who was the king’s official, and who could, as such, be replaced at any time. However, in a rather short time, Gaugraf came to be more and more an hereditary post held by Gaugraf families. Beginning in 960, one such family cropped up in the Nahegau: the Emichones. Beginning in the mid 11th century, the Emichones were known to hold the countship and its attendant fief as heritable property, and they were also Imperially immediate princes. The Emichones were related to the Frankish Imperial dynasty, the Salians, whose family holdings lay in the Middle Rhine area. As a result of the fief law decreed by Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor, all fiefs, great and small, became heritable property.

Also belonging to the Emichones’ main line beginning in 1103 were the Wildgraves. After several partitions of the Waldgraviate – to which belonged Schmidtburg, Kyrburg, Dhaun and Grumbach – Bruchweiler, and Kempfeld, too, passed in 1282 to Gottfried von Kyrburg. In 1328, the Wildenburg (castle) was built by Friedrich von Kyrburg. After the Schmidtburg, Dhaun and Kyrburg Waldgraves died out in the male line, the whole Waldgraviate passed to the last Wildgrave’s son-in-law, Rhinegrave John III (whose last comital seat was Rheingrafenstein Castle near Bad Münster am Stein-Ebernburg) as an inheritance. Thereafter, his noble house called itself “Wild- and Rhinegraves”. Even after several lines emerged as the result of division of inheritance, this comital house remained one of the most powerful lordly houses between the Moselle and the Nahe, until Napoleon annexed the lands on the Rhine’s left bank in 1798 after the French Revolution.

As for the local people themselves, in Frankish-Early German times, they were all free peasants with the same rights. However, under the Heerbanngesetz (“Army Ban Law”), all free peasants had to perform long defence drills and military service, which made tending their fields properly ever more difficult. To free themselves from military service, many free peasants transferred their farms to a lord’s ownership so that the lord could then enfeoff the peasant with the same farm. Although this released the peasant from military service, it did mean that he then had to pay tributes to his lord.

Since all power, prestige and income was linked to land ownership, each lord sought to expand his holdings by amassing as many of these small feudal landholds as he could and adding them to his own holdings. Thus, over centuries, all land ended up being held by lords, both secular and ecclesiastical. Bruchweiler belonged, within the Waldgraves’ and Rhinegraves’ holdings, to the Amt of Wildenburg, where the count’s Amtmann ("bailiff") could more or less do whatever he deemed fit, without any meaningful constraints on his power locally.

It may be supposed that the villages in the Bruchweiler area already existed in the 10th century and that, indeed, they had already arisen by Roman times. Places with names ending in —weiler might originally have earned that placename ending from the Latin word villa, meaning a lone house or an estate (modern-day German still uses Weiler as a standalone word meaning “hamlet”). The assumption is strengthened by the Roman graves found in the Bruchweiler area (see above).

In Bruchweiler, the Count of Sponheim-Kreuznach, too, had several subjects who were obliged, whenever the bell sounded the Waffengeschrey (“call to arms”), to do the Waldgrave’s bidding.

Sponheim was forbidden to hold more than four estates in Bruchweiler. This was stipulated in a document issued by Waldgrave Emich von Kyrburg and Count Johann von Sponheim in 1279 (which, among other things, also gave Bruchweiler its first documentary mention as bruchvillare). That was the time of Faustrecht (“Fist Law”), in which feuds and other violence were the order of the day as lords tried to emerge over others as the dominant rulers.

Taxes and services were a hefty burden in the Middle Ages on the inhabitants. As well as the Besthaupt (“best head”, that is, head of cattle), the payment from a serf’s estate upon his death to the Wildenburg of his best head of cattle, there were also the Schatzung (a direct tax), the Bede (ground rent), endless tithes and compulsory labour for the lord.

By 1546, Martin Luther’s teachings had found their way into many municipalities in the Hunsrück. After the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, which granted landed lords the right to determine their subjects’ religion (cuius regio, eius religio), the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves openly embraced Luther’s teachings and introduced the Reformation into their lands. Morning and afternoon peals were introduced to remind people to pray. The church in Bruchweiler belonged to the parish of Wirschweiler. The church building that stands today was built in 1744. Bruchweiler is an autonomous parish tied with Sensweiler through a personal union.

The Thirty Years' War wrought upon Bruchweiler – as it did upon every part of Germany – great havoc. As early as 1620, the village was hosting 25,000 Spaniards and Walloons fighting on the Imperial side. Since the Waldgraves and Rhinegraves had sided with the Swedes, though, this was a dire situation. For a time, there was also a Swedish occupation.

The conditions were bleak. In 1635, two thirds of the inhabitants had died. What the troops did not destroy was taken away by the Plague and hunger. It was at this time that the village of Schalwen near Kempfeld was utterly wiped out.

The peace concluded at Münster and Osnabrück took a long time to bring about anything resembling normalcy. Mercenaries who had been released from service went about the countryside begging and plundering. Because this problem seemed neverending in the Bruchweiler area, with its hordes of Lothringer (“Lorrainians”) always causing trouble, the Rhinegrave forged an agreement with the Elector of the Palatinate whereby each would help the other protect his territory from the marauders. To this end, a force of 2,000 men – 1,700 foot soldiers and 300 mounted men – was assembled. The Rhinegrave’s and Count Palatine’s efforts notwithstanding, the “Lorrainian” horde managed to take the Wildenburg in 1652 and to destroy it.

When in the wake of the Thirty Years' War German kings’ power had declined and Germany had splintered into more than 300 statelets, some of the king’s rights passed to the princes. Among the Waldgraves’ and Rhinegraves’ lordly rights by 1648 were military, judicial and customs authority, the right to mint coins and all mining rights. These rights represented important income sources for the lord, as other lordly rights pertaining to water, forest, grazing land, hunting and fishing always had.

The wounds inflicted by the Thirty Years' War had not yet healed when King Louis XIV’s forces thronged into the Hunsrück, taking the Wildenburg. People from throughout the area had to do compulsory labour, building the fort of Montroyal (near Traben-Trarbach). If indeed the Wildenburg had ever served as a stronghold guarding the Waldgraves’ and Rhinegraves’ holdings in the Bruchweiler area, it was now losing that function. By this time, the castle was little more than a ruin. Firearms, now in common use, had rendered mediaeval fortifications almost useless anyway, and little work was ever again done to restore the castle. Later, the Amtshaus, built in 1660, served the purpose of administration. The Wildenburg nevertheless remained the embodiment of the Waldgravial-Rhinegravial high jurisdiction and lordship.

After the commotion and destruction wrought by the Thirty Years' War and the time that followed, there was enormous growth in the demand for ironware and iron equipment. In response, new ironworks, iron and copper smelters and hammermills soon arose. As early as 1670, the Asbacher Hütte (Asbach Foundry) came into being, which drew its ore from mines near Niederwörresbach and Berschweiler, where rich iron deposits had been discovered. Joining the foundry in 1714 were the Hammer Birkenfeld – popularly called the Schippenhammer – and the steel- and hammermill in Sensweiler. There were also the Katzenloch hammermill, opened in 1758, and the Allenbach copper smelter, which in 1802 was converted to an iron hammermill. At the hammermills, the iron produced by the Asbach Foundry was wrought into various kinds of ironware. Besides smiths, charcoal makers and goods transporters were first and foremost needed.

Slowly, the ironworks once again allowed trade and business to blossom. Hundreds of families from the local area were working and earning a living at the Stummsche Hüttenwerke by the late 18th century, be it as sand mould makers, pourers, modellers, metal engravers, charcoal makers, ore miners or goods transporters. The ironware made at the ironworks was shipped in all directions, to Mainz, Koblenz, Cologne, Trier, Luxembourg and other places.

The French Revolution also had its historical consequences for the Bruchweiler area. In 1792, French Revolutionary troops advanced across the Hunsrück as far as Mainz. The whole area on the Rhine’s left bank was occupied by the French. To what was left of the feudal system, fiefs, princes and serfdom was put a quick end. On 7 March 1798, the Amt of Wildenburg ceased to exist, and with the new division of administration, the Bruchweiler area found itself in the arrondissement of Birkenfeld in the Department of Sarre. Bruchweiler itself was grouped into the Mairie (“Mayoralty”) of Hottenbach in the canton of Herrstein. Serfdom was abolished, and some other improvements for personal freedom, such as right of abode, were introduced. Even so, the compulsory labour and all the taxes and tithes that had characterized pre-Revolutionary times were gone, only to be replaced by French taxes that were every bit as heavy.

One thing that made clear how disorderly the times around 1800 were was the crime, particularly robbery. Schinderhannes (Johannes Bückler) then held the people under his spell.

French hegemony came to an end in 1814. After the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the Bruchweiler area found itself on 22 April 1816 in the Kingdom of Prussia. It was then that the Regierungsbezirk of Trier arose; the Bernkastel district was also newly formed. At first, Bruchweiler was grouped into the Amt of Rhaunen, but in 1851 it was transferred along with Kempfeld and Schauren to the Bürgermeisterei (“Mayoralty”) of Wirschweiler. In 1886, the administrative seat was moved to Kempfeld.

Bruchweiler’s population figure in 1680 was given as 14 families. By 1698 this had fallen to only 5 families.

- 1740 – 10 families

- 1802 – 174 inhabitants

- 1809 – 180 inhabitants

- 1849 – 319 inhabitants

- 1882 – 400 inhabitants

The strong growth in the population in the 19th century can be traced to the influence and development of the iron industry in neighbouring villages. Bruchweiler experienced a surge about 1846. Agate polishing gained a foothold in the village. Even today, gemstones are skilfully cut and polished in workshops.

Even into the time after the Second World War, agriculture was always the local inhabitants’ main income earner. The Flurbereinigung undertaken between 1934 and 1938 allowed farm mechanization to quickly make great strides, although a full set of farm machinery was only worth having for bigger farms. This led to a considerable fall in the number of smaller farms, especially after 1948. This in turn led to a shift in the village’s economic structure, one that became all the more obvious in 1955 when a technical stone factory – one in which stone is processed into useful articles – opened, as well as the realization that some 50 inhabitants were commuting to work every morning on postbuses to jobs that lay outside the village, mainly in Idar-Oberstein.

It was also after the war that a new neighbourhood arose in the village, a residential area in whose middle stands a school building dating from 1956. The municipality’s population is now above the 500 mark.[2]

Since 1946, Bruchweiler has been part of the then newly founded state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Until administrative restructuring in Rhineland-Palatinate in 1969, Bruchweiler belonged to the now abolished district of Bernkastel.

Politics

Municipal council

The council is made up of 12 council members, who were elected by majority vote at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman.[3]

Mayor

Bruchweiler’s mayor is Horst Scherer, and his deputies are Hartmut Hartmann and Volker Luckenbach.[4][5]

Coat of arms

The German blazon reads: In schräg geteiltem Schild vorne in Rot vier silberne quadratische Steine, hinten in Gold ein blaubewehrter und -gezungter roter Löwe.

The municipality’s arms might in English heraldic language be described thus: Per bend gules four cubes argent and Or a lion rampant of the first armed and langued azure.

The German blazon does not specify the distribution of the “cubes”, called “silver square stones” in the original German. “Square” cannot be used in the English blazon as this refers to a different charge, namely an L-shaped carpentry tool.[6][7]

The escutcheon’s dexter (armsbearer’s right, viewer’s left) side refers by its tinctures (gules and argent, or red and silver) to the arms once borne by the Counts of the “Hinder” County of Sponheim. The “square stones” symbolize the four Sponheim free estates within the Waldgravial-Rhinegravial domain. The charge on the sinister (armsbearer’s left, viewer’s right) side, the lion rampant, is a reference to the village’s former allegiance to the Waldgraviate-Rhinegraviate.[8]

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[9]

- Evangelical church, Hochwaldstraße 5 – aisleless church with ridge turret, 1744-1746; décor

- Hochwaldstraße 2 – Quereinhaus (a combination residential and commercial house divided for these two purposes down the middle, perpendicularly to the street), partly timber-frame, half-hipped roof, earlier half of the 19th century

References

- ↑ "Gemeinden in Deutschland mit Bevölkerung am 31. Dezember 2015" (PDF). Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). 2016.

- ↑ Bruchweiler’s history Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kommunalwahl Rheinland-Pfalz 2009, Gemeinderat

- ↑ Bruchweiler’s mayor Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Mayor’s deputies Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ James Parker on the “square”

- ↑ James Parker on the “cube”

- ↑ Description and explanation of Bruchweiler’s arms Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Directory of Cultural Monuments in Birkenfeld district

External links

- Municipality’s official webpage (German)