Brook floater

| Brook floater | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Unionoida |

| Family: | Unionidae |

| Genus: | Alasmidonta |

| Species: | A. varicosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Alasmidonta varicosa (Lamarck, 1819) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Alismodonta varicosa (Lamarck, 1819) | |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alasmidonta varicosa. |

The brook floater (also known as swollen wedgmussel),[1] Alasmidonta varicosa, is a species of freshwater mussel, an aquatic bivalve mollusk in the family Unionidae, the river mussels. It measures 25.1 mm to 80.2 mm in length[2] although other research also suggests it rarely exceeds three inches (75 mm).[1]

Distribution

This species is found in Canada (New Brunswick and Nova Scotia)[3] and northeastern United States (Connecticut, Georgia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia and West Virginia);[4] It was formerly found in Rhode Island and four watersheds in Massachusetts.[1] 1897 Research by Arnold Edward Ortmann showed it to be common in the Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers.[5]

Habitat and behavior

This mussel lives in high relief streams, under boulders and in sand. Research has shown that it is highly sensitive to increased thermal temperature.[6] It associates with longnose and blacknose dace, golden shiner, pumpkinseed, slimy sculpin and yellow perch.[7]

Survival threats and conservation

The brook floater is sensitive to habitat loss for development, dams and road crossings, pollution, summer droughts, trampling, sedimentation, flow alteration, and low oxygen conditions. Hybridization with elktoe (Alasmidonta marginata), a longtime ally, has also shown to be a threat.[8] Research has also shown the population is highly fragmented, low in density, prone to mortality due to old age and there are also low chances of longevity and viable reproduction.[1] Trematoda rhopalocercous cercaria is a parasite of the brook floater.[9] Current research shows population that were largely and widespread known declined by 50% t0 95% to almost extinct.[10]

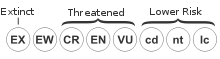

While the IUCN lists it as Data Deficient, the states of New Jersey, Virginia, Massachusetts and New Hampshire[1] all list it as Endangered,[11] Threatened in Vermont, Maine and New York,[12] Rare/Endangered in Connecticut,[7] and "Species of Special Concern" by the federal government.[13]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nedeau, Ethan (2007). "Brook Floater" (PDF). mass.gov. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ Janet L. Clayton, Craig W. Stihler and Jack L. Wallace (2001). "STATUS OF AND POTENTIAL IMPACTS TO THE FRESHWATER BIVALVES (UNIONIDAE) IN PATTERSON CREEK, WEST VIRGINIA". bioone.org. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ Caroline Caissie, Dominique Audet, Freshwater Mussel Inventory in the Shediac and Scoudouc Rivers, New Brunswick Wildlife Trust Fund, 2006, p. 12. Accessed August 21, 2014

- ↑ "Brook floater (Alasmidonta varicosa)". ecos.fws.gov. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ Arnold Edward Ortmann (1897). Collected papers, Volume 1. self-published. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Thermal History Impacts Thermal Tolerance of Freshwater Mussels". co2science.org. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- 1 2 Hammerson, Geoffrey A. (2004). Connecticut Wildlife: Biodiversity, Natural History, and Conservation. University Press of New England. p. 205. ISBN 1584653698. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Changes in the Distribution of Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae) in the Upper Susquehanna River Basin, 1955–1965 to 1996–1997". bioone.org. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Cercaria tiogae Fischthal, 1953, a Rhopalocercous Form from the Clam, Alasmidonta varicosa (Lamarck)". American Microscopical Society. 1954. JSTOR 3223759.

- ↑ "The conservation status of the brook floater mussel, Alasmidonta varicosa, in the Northeastern United States: trends in distribution, occurrence, and condition of populations". rcngrants.org. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ Thomas F. Nalepa, Don W. Schloesser (2013). Quagga and Zebra Mussels: Biology, Impacts, and Control, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 206. ISBN 1439854378. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ McBroom, Matthew (2013). The Effects of Induced Hydraulic Fracturing on the Environment: Commercial Demands vs. Water, Wildlife, and Human Ecosystems. CRC Press. p. 285. ISBN 1926895835. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ Bruce E. Beans, Larry Niles (2003). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife of New Jersey. Rutgers University Press. p. 257. ISBN 0813532094. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Bogan, A.E 2000. Alasmidonta varicosa. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 6 August 2007.