British railway milk trains

Milk trains were a common sight on the railways of Great Britain from the early 1930s to the late 1960s. Introduced to transport raw milk from creameries to food processing units in remote locations, they were the last railway-based system before the mass-introduction of pasteurization and the resultant industry use of road transport.

History

By 1923, the year in which almost all the railways in Great Britain were grouped into four national companies, 282 million gallons of milk were being transported annually by rail.[1] Of this traffic the Great Western Railway, serving the rural and highly agricultural West of England and South Wales, had the largest share. It was followed by the LMS, which collected from Cumbria and North Wales; the Southern, deriving the bulk of its traffic from the Somerset and Dorset Railway; and finally the LNER, which served East Anglia.[1]

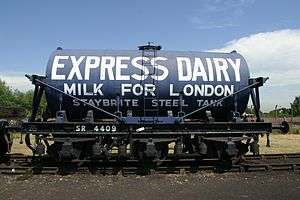

The Milk Marketing Board (MMB) was created in 1933 and in 1942, during World War II, took control of all milk transport. By the late 1960s the MMB had switched entirely to road haulage, and only Express Dairies and Unigate continued to use rail transport.

Operations

_Down_milk_empties_geograph-2646794-by-Ben-Brooksbank.jpg)

A typical creamery would load a couple of milk tank wagons a day, with a single 3,000-imperial-gallon (14,000 l; 3,600 US gal) three-axle wagon carrying enough pasteurised milk to supply the daily needs of about 35,000 people. However, that same 12-long-ton (12,000 kg) wagon loaded with 3,000 imperial gallons (14,000 l; 3,600 US gal) of milk at 13 long tons (13 t; 15 short tons), weighed as much as a loaded passenger carriage: 25 long tons (25 t; 28 short tons). This resulted in the need to pull the heavy milk train with a high-powered express locomotive, in order to keep time delays to a minimum. Typical GWR locomotives deployed on milk trains included topline express lococmotives such as Kings, Castles and Halls, unlike the archetypal mixed-goods express or even slower but equally heavy coal train. After dieselisation in the 1960s, Western diesels were deployed on milk trains, again a typical passenger express locomotive on the time.[1]

Milk tank wagons were distributed around the small local creameries in the afternoon, and then collected by the first train in the morning. On the GWR, it was not uncommon to see a pannier tank engine and GWR autocoach on a local passenger service pulling a milk tank wagon early in the morning. After 1959 four- and six-wheeled goods vehicles were banned from passenger trains, and so dedicated milk trains were scheduled. These smaller numbers of milk tank wagons were collected at the nearest mainline station or junction goods yard, and then either became the nucleus of a new milk train heading towards London, or were attached to a dedicated passing milk train that had started further down the mainline.[1]

In the 1960s, the average shipping distance for milk was 250 miles (400 km) by rail. As most milk is produced in the West Country (where the rain falls), but consumed in London and the East where the bulk of the population resides, most milk trains were west-east running. Express Dairies had two major depots in London: one in Kensington, which took deliveries from the GWR and SR; and one in Hendon which took deliveries shipped by the LMS from Carlisle, then the longest dedicated milk train route in the United Kingdom. The term "milk run" became synonymous in railway terms and later the English language, as a routine trip where the timetable was set and remained unaltered.[1]

The SR and later the Southern Region of British Railways ran two regular milk trains from Torrington every day, which served both the United Dairies creamery and bottling plant at Vauxhall, and the Express Dairies creamery at Morden. Filled by road tankers from the Torridge Vale Dairies, the first train of eight wagons left Torrington at 14:47, the second of six at 16:37, split due to the weight of the full milk tank wagons. The first train arrived at Clapham Junction in the evening, and reduced its length by half so that it did not block Vauxhall station while unloading. It would then proceed to Vauxhall, and pull into the "down" side platform, where a discharge pipe was provided to the creamery on the other side of the road. There was also pedestrian access from below the station, under the road to the depot, in the tunnel where the pipeline ran. The unloaded train would then proceed to Waterloo, where it would reverse and return to Clapham Junction to pick up the other half of the train. The procedure was then repeated, so that the entire first milk train was unloaded between the end of evening peak traffic and the start of the following morning. The second train from Torrington would also split at Clapham Junction, but only half of its milk tanks would be propelled to Vauxhall, while the other half were dispatched to the Express Dairies depot at Morden. In the late morning, both trains' now empty milk tanks would be combined into one express train, and returned to Torrington. Milk trains from Torrington stopped in 1978, the last milk train on the former SR.[2]

The longest surviving milk runs were from Fishguard in West Wales, and Long Rock near Penzance, both to the former Express Dairies plant then run by the MMB at Kensington (Olympia), West London. The Cornish train would pick up at: Lostwithiel; Totnes for Ashburton; Exeter for both Hemyock and Torrington; then direct via Tiverton Junction to Kensington. Although both trains were only scheduled to travel once a day in either direction, the 70,000,000 imperial gallons (320,000,000 l; 84,000,000 US gal) that they shipped annually still represented 25% of the UK's total milk shipment.[1]

After loss of the Cornish and Welsh contracts in 1981, it was also the last year that operational use was made of milk tank wagons in the United Kingdom. Using refurbished two- and three-axle wagons, the MMB had newly manufactured 5-foot-6-inch (1.68 m) diameter aluminium milk tanks chain-anchored to the chassis. Painted in MMB blue, they were mounted on a black chassis with black chains, all white lettering and orange axle-box covers. Given the TOPS code TRV, they operated on the short-lived Chard Junction to Stowmarket service for less than a year.[1] After the contract was cancelled, the MMB kept the refurbished milk tank wagons in store on their own premises to overcome any difficulties in road transport, before disposing of the entire fleet five years later.[1]

List of railway connected dairies, 1956

The following is a list of railway connected dairies and creameries in 1956:[3]

| Dairy | Stations | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carnation Milk | Dumfries | LMS |

| Cow & Gate | Lostwithiel, Newcastle Emlyn, Wincanton | Also known as Dried Milk Products/DMP |

| CWS Dairies | Llangadog, Melksham, Wallingford[4] | GWR |

| Egginton Dairy | Egginton Junction | LNER |

| Express Dairies | Acton,[5] Appleby, Cricklewood, Frome, Horam, Kensington (Olympia), Leyburn, Morden,[2] Pipe Gate, Rowsley, St Helier | Express generally preferred deliveries via the GWR |

| London Co-operative Society | Puxton, West Ealing | GWR |

| J. Lyons and Co. | Greenford[6] | GWR via the New North Main Line for Lyons Maid[6] |

| Midland Counties Dairy | Welshpool | GWR via the Cambrian Line |

| Milk Marketing Board | Egremont, Felin Fran, Four Crosses, Pont Llanio, Sturminster Newton | |

| Nesmilk | Ashbourne, Bow, Carlisle, Congleton, Holt Junction,[7] Martock, Tutbury | |

| Primrose Dairy | St Erth | GWR. Later sold to United Dairies |

| Scottish MMB | Dalry, Dalbeattie | |

| United Dairies | Bailey Gate, Calverley, Carmarthen, Ealing Broadway, Finchley, Mitre Bridge Junction, Shepherds Bush, Vauxhall,[2] Welford, Whitland, Wootton Bassett Junction,[8] Yetminster | United generally preferred deliveries via the SR |

| Wilts United Co-op | Bason Bridge, Buckingham,[9] Chard Junction, Hemyock, Nine Elms, Uttoxeter | |

Milk train in popular usage

The phrase 'catching the milk train' remains in usage in English to describe catching a very early train.[10][11] It may also be used to describe rising early in the morning.[12]

See also

References

- B.K. Coopers. Great Western Railway Handbook.

- Dave Larkin. BR General Parcels Rolling Stock. D Bradford Barton.

- Jim Russell (1972). Pictorial Record of Great Western Coaches Part 1 1838-1913. Oxford Publishing.

- Atkins, A.G.; Beard, W.; Hyde, D.J.; Tourret, R. (1975). A history of GWR Goods Wagons, Volume 1. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-6532-0.

- Atkins, A.G.; Beard, W.; Hyde, D.J.; Tourret, R. (1976). A history of GWR Goods Wagons, Volume 2. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7290-4.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/gansg/7-fops/fo-milk.htm

- 1 2 3 "The Torrington Milk Train". SVS Films. 2012-01-21.

- ↑ http://www.railforums.co.uk/showthread.php?t=39434&page=2

- ↑ Antony Ewart Smith (1960). "The CWS Creamery on Borough Road circa 1960". geograph.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ↑ "South Acton Station". Abandoned Stations. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- 1 2 "The First Food Empire: A History of J.Lyons & Co". Peter Bird. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- ↑ "Gillespies Report" (PDF). Wiltshire County Council. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ↑ Oakley, Mike (2004). Wiltshire Railway Stations. Wimbourne: The Dovecote Press. ISBN 1-904349-33-1.

- ↑ Simpson, Bill (1994). Banbury to Verney Junction Branch. Banbury, Oxfordshire: Lamplight Publications. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-899246-00-7.

- ↑ "milk train". oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ "milk train". collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ Dow, Andrew (2006). Dow's Dictionary of Railway Quotations. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 242. ISBN 0801882923. Retrieved 11 November 2014.