Botta's pocket gopher

| Botta's pocket gopher | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Geomyidae |

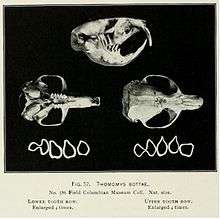

| Genus: | Thomomys |

| Species: | T. bottae |

| Binomial name | |

| Thomomys bottae (Eydoux and Gervais, 1836) | |

| |

| Botta's pocket gopher range | |

Botta's pocket gopher (Thomomys bottae) is a pocket gopher native to western North America. It is also known in some sources as valley pocket gopher, particularly in California. Both the specific and common names of this species honor Paul-Émile Botta, a naturalist and archaeologist who collected mammals in California in the 1820s and 1830s.

Description

Botta's pocket gopher is a medium-sized gopher, with adults reaching a length of 18 to 27 centimetres (7.1 to 10.6 in), including a 5 to 6 centimetres (2.0 to 2.4 in) tail.[2] Males are larger, with a weight of 160–250 grams (5.6–8.8 oz), compared with 120–200 grams (4.2–7.1 oz) in the females.[3] Coloration is highly variable, and has been used to help distinguish some of the many subspecies; it may also change over the course of a year as the animals molt.[4] Both albino and melanistic individuals have also been reported. However, Botta's gopher generally lacks the black stripe down the middle of the back found in the closely related southern pocket gopher, a feature that may be used to tell the two species apart where they live in the same area.[2]

Distribution

Botta's pocket gophers are found from California east to Texas, and from Utah and southern Colorado south to Mexico. Within this geographical area, they inhabit a range of habitats, including woodlands, chaparral, scrubland, and agricultural land, being limited only by rocky terrain, barren deserts, and major rivers.[2] They are found at elevations up to at least 4,200 metres (13,800 ft).[5] Skeletal remains of Botta's pocket gophers, dating back 31,000 years, have been identified from Oklahoma.[6]

Around 195 subspecies have been described, mostly on the basis of geographical distribution. Some of these have previously been described as distinct species in their own right. The distribution of the type localities of these subspecies is as follows:[2]

- California - 43 (including the nominate subspecies)

- Oregon - 2 (both in the extreme south of the state)

- Nevada - 16

- Utah - 20

- Arizona - 43

- New Mexico - 15

- Colorado - 4

- Texas - 10 (all in the western region of the state)

- Baja California - 16

- Baja California Sur - 8

- Sonora - 8

- Chihuahua - 2

- Coahuila - 6

- Sinaloa - 2 (both in the extreme north of the state)

Ecology

Botta's pocket gopher is strictly herbivorous, feeding on a variety of plant matter. Shoots and grasses are particularly important, supplemented by roots, tubers, and bulbs during the winter.[2] An individual will often pull plants into the ground by the roots to consume them in the safety of its burrow, where it spends 90% of its life.

Main predators of this species include American badgers, coyotes, long-tailed weasels, and snakes, but other predators include skunks, owls, bobcats, and hawks. This species is considered a pest in urban and agricultural areas due to its burrowing habit and its predilection for alfalfa; however, it is also considered beneficial as its burrows are a key source of aeration for soils in the region.

Digging by Botta's pocket gophers is estimated to aerate the soil to a depth of about 20 centimetres (7.9 in),[2] and to be responsible for the creation of Mima mounds up to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) in height. Populations of the species have been estimated to mine as much as 28 tonnes of soil per hectare per year, much of which is moved below ground, rather than being pushed up into the mounds.[7] On the negative side, the species has been associated with the deaths of aspen in Arizona[8] and creates patches of bare ground that may limit the establishment of new seedlings.[9]

Behavior

Botta's pocket gopher is highly adaptable, burrowing into a very diverse array of soils from loose sands to tightly packed clays, and from arid deserts to high altitude meadows. They are able to tolerate such a wide range of soils in part because they dig primarily with their teeth, which are larger and with a thicker layer of enamel than in claw-digging gophers. In comparison, gophers digging with their claws are generally only able to dig in softer soils, because their claws wear down more quickly than teeth do in harder materials.[10]

Botta's pocket gophers are active for a total of about nine hours each day, spending most of their time feeding in their burrows, but are not restricted to either daylight or night time.[11] They make little sound, although they do communicate by making clicking noises, soft hisses, and squeaks.[2]

Their burrows include multiple deep chambers for nesting, food storage, and defecation, that be as much as 1.6 metres (5 ft 3 in) below ground. A series of tunnels close to the surface are used for feeding on plant roots, and have shorter side tunnels for disposal of excavated soil. On the surface, the burrows are marked by fan-shaped mounds of excavated soil, with the actual entrance usually kept filled in for protection.[2] Population densities of between 10 and 62 per acre (25 and 153/ha) have been reported.[2]

Aboveground traces of these burrows are sometimes called "gopher eskers."

Outside of the breeding season, each burrow is inhabited by a single adult, with any young leaving once they are weaned. Male burrows extend over a mean area of 474 square metres (5,100 sq ft), and those of females 286 square metres (3,080 sq ft),[12] but the gophers aggressively defend[13] a larger exclusive area, of 810 square metres (8,700 sq ft) for males and 390 square metres (4,200 sq ft) for females, around the burrow entrance.[2]

Reproduction

In areas with sufficient food, such as agricultural land, breeding can occur year round, with up to four litters being born each year. In the north, and other, less hospitable, environments, it occurs only during the spring. The local habitat also affects the age at which females begin breeding, with nearly half doing so in their first year in agricultural land, but none at all in desert scrub.[2]

Gestation lasts eighteen days, and results in the birth of a litter of up to twelve pups, although three or four is more typical. The young are born hairless and blind, and measure about 5 centimetres (2.0 in) in length.[2] The first, silky coat of fur is replaced by a coarser coat of grey hair as the pups age, before the full adult coat develops.[4]

Botta's pocket gophers are capable of breeding with southern pocket gophers, and, until the 1980s, were often considered to belong to the same species. However, male hybrids are sterile, and females have greatly reduced fertility and rarely have offspring of their own.[14] Hybridisation with Townsend's pocket gopher has also been reported, and it too appears not to extend much beyond the first generation.[15]

References

- ↑ Linzey, A.V.; Timm, R.; Álvarez-Castañeda, S.T. & Lacher, T. (2008). "Thomomys bottae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 15 March 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Jones, C.A. & Baxter, C.N. (2004). "Thomomys bottae". Mammalian Species. 742: Number 742: pp. 1–14. doi:10.1644/742.

- ↑ "Thomomys bottae". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- 1 2 Morejohn, G.V. & Howard, W.E. (1956). "Molt in the pocket gopher, Thomomys bottae". Journal of Mammalogy. 37 (2): 201–213. doi:10.2307/1376679. JSTOR 1376679.

- ↑ Bole B.P., jr. (1938). "Some altitude records for mammals in the Inyo-White Mountains of California". Journal of Mammalogy. 19 (2): 245–246. doi:10.2307/1374623. JSTOR 1374623.

- ↑ Dalquest, W.W.; et al. (1990). "Zoogeographic implications of Holocene mammal remains from ancient beaver ponds in Oklahoma and New Mexico". The Southwestern Naturalist. 35 (2): 105–110. doi:10.2307/3671529. JSTOR 3671529.

- ↑ Cox, G.W. (1990). "Soil mining by pocket gophers along topographic gradients in a Mima moundfield". Ecology. 71 (3): 837–843. doi:10.2307/1937355. JSTOR 1937355.

- ↑ Cantor, L.F. & Whitham, T.G. (1989). "Importance of belowground herbivory: pocket gophers may limit aspen to rock outcrop refugia". Ecology. 70 (4): 962–970. doi:10.2307/1941363. JSTOR 1941363.

- ↑ Stromberg, J.C. & Patten, D.T. (1991). "Dynamics of the spruce-fir forests on the Pinaleno Mountains, Graham Co., Arizona". The Southwestern Naturalist. 36 (1): 37–48. doi:10.2307/3672114. JSTOR 3672114.

- ↑ Lessa, E.P. & Thaela C.S., jr. (1989). "A reassessment of morphological specializations for digging in pocket gophers". Journal of Mammalogy. 79 (4): 689–700. doi:10.2307/1381704. JSTOR 1381704.

- ↑ Gettinger, R.D. (1984). "A field study of activity patterns of Thomomys bottae". Journal of Mammalogy. 65 (1): 76–84. doi:10.2307/1381202. JSTOR 1381202.

- ↑ Bandoli, J.H. (1987). "Activity and plural occupancy of burrows in Botta's pocket gopher Thomomys bottae". American Midland Naturalist. 118 (1): 10–14. doi:10.2307/2425623. JSTOR 2425623.

- ↑ Baker, A.E.M. (1974). "Interspecific aggressive behavior of pocket gophers Thomomys bottae and T. talpoides (Geomyidae: Rodentia)". Ecology. 55 (3): 671–673. doi:10.2307/1935160. JSTOR 1935160.

- ↑ Patton, J.L. (1973). "An analysis of natural hybridization between the pocket gophers, Thomomys bottae and Thomomys umbrinus, in Arizona". Journal of Mammalogy. 54 (3): 561–584. doi:10.2307/1378959. JSTOR 1378959.

- ↑ Patton, J.L.; et al. (1984). "Genetics of hybridization between the pocket gophers, Thomomys bottae and Thomomys townsendii in northeastern California". Great Basin Naturalist. 44 (3): 431–440. JSTOR 41712092.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomomys bottae. |

Data related to Thomomys bottae at Wikispecies

Data related to Thomomys bottae at Wikispecies- DesertUSA - profile

- eNature - profile

- The Mammals of Texas - profile