Bohemond I of Antioch

| Bohemond I | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Portrait by François-Edouard Picot | |

| Prince of Antioch | |

| Tenure | 1098–1111 |

| Successor | Bohemond II |

| Born |

c. 1054 San Marco Argentano, Calabria |

| Died | 3 March 1111 (aged 57) |

| Spouse | Constance of France |

| Issue | Bohemond II of Antioch |

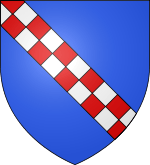

| House | Hauteville family |

| Father | Robert Guiscard |

| Mother | Alberada of Buonalbergo |

Bohemond I (c. 1054 – 3 March 1111) was the Prince of Taranto from 1089 to 1111 and the Prince of Antioch from 1098 to 1111. He was a leader of the First Crusade, which was governed by a committee of nobles.[1] The Norman monarchy he founded in Antioch arguably outlasted those of England and of Sicily.[2]

Early life

Childhood and youth

Bohemond was the only child of Robert Guiscard, Count of Apulia and Calabria, and his first wife, Alberada of Buonalbergo.[3][4] He was born between 1050 and 1058—in 1054 according to historian John Julius Norwich.[5][6] He was baptised Mark, possibly because he was born at his father's castle at San Marco Argentano in Calabria.[7][5] He was nicknamed Bohemond after a legendary giant.[5]

His parents were related within the degree of kinship that made their marriage invalid under canon law.[3] In 1058, Pope Nicholas II strengthened existing canon law against consanguinity and, on that basis, Guiscard repudiated Alberada in favour of a then more advantageous marriage to Sikelgaita, the sister of Gisulf, the Lombard Prince of Salerno.[4][8] With the annulment of his parents' marriage, Bohemond became a bastard.[4][9] Before long, Alberada married Robert Guiscard's nephew, Richard of Hauteville.[8] She arranged for a knightly education for Bohemond.[10]

Robert Guiscard was taken seriously ill in early 1073.[11][12] Fearing that he was dying, Sikelgaita held an assembly in Bari.[12] She persuaded Robert's vassals who were present to proclaim her eldest son, the thirteen-year-old Roger Borsa, Robert's heir, claiming that the half-Lombard Roger would be the ruler most acceptable to the Lombard nobles in Southern Italy.[11][13] Robert's nephew, Abelard of Hauteville, was the only baron to protest, because he regarded himself Robert's lawful heir.[14]

Byzantine wars

Bohemond fought in his father's army during the rebellion of Jordan I of Capua, Geoffrey of Conversano and other Norman barons in 1079.[10] His father dispatched him at the head of an advance guard against the Byzantine Empire in early 1081[15] and he captured Valona (now Vlorë in Albania).[15] He sailed to Corfu, but did not invade the island since the local garrison outnumbered his army.[16] He withdrew to Butrinto to await the arrival of his father's forces.[16] After Robert Guiscard arrived in the latter half of May, they laid siege to Durazzo (present-day Durrës).[16] The Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos came to the rescue of the town but, on 18 October, his army suffered a crushing defeat.[17] Bohemond commanded the left flank, which defeated the Emperor's largely Anglo-Saxon "Varangian Guard".[17][18]

The Normans captured Durazzo on 21 February 1082.[19][20] They marched along the Via Egnatia as far as Kastoria, but Alexios's agents stirred up a rebellion in Southern Italy, forcing Robert Guiscard to return to his realm in April.[20][21] He charged Bohemond with the command of his army in the Balkans.[22] Bohemond defeated the Byzantines at Ioannina and at Arta, taking control of most of Macedonia and Thessaly;[23] however, the six-month siege of Larissa was unsuccessful.[23] Supply and pay problems (and the gifts promised to deserters by the Byzantines) undermined the morale of the Norman army,[23][24] so Bohemond returned to Italy for financial support.[24] During his absence, most of the Norman commanders deserted to the Byzantines and a Venetian fleet recaptured Durazzo and Corfu.[24]

Bohemond accompanied his father to the Byzantine Empire again in 1084,[15][24] when they defeated the Venetian fleet and captured Corfu.[15] An epidemic decimated the Normans[21] and Bohemond, who was taken seriously ill, was forced to return to Italy in December 1084.[21][25]

Succession crisis

Robert Guiscard died at Cephalonia on 17 July 1085.[25] Ordericus Vitalis, William of Malmesbury and other contemporaneous writers accused his widow, Sikelgaita, of having poisoned Robert to secure Apulia for her son, Roger Borsa, but failed to establish her guilt.[26] She persuaded the army to acclaim Roger Borsa his father's successor and they hurried back to Southern Italy.[27][28] Two months later, the assembly of the Norman barons confirmed the succession, but Bohemond regarded himself his father's lawful heir.[29] He made an alliance with Jordan of Capua, and captured Oria and Otranto.[30][31] Bohemond and Roger Borsa met at their father's tomb at Venosa to reach a compromise.[31] Under the terms of their agreement, Bohemond received Taranto, Oria, Otranto, Brindisi and Gallipoli, but acknowledged Roger Borsa's suzerainty.[31]

Bohemond renewed the war against his brother in the autumn of 1087.[32] The ensuing civil war prevented the Normans from supporting Pope Urban II, and enabled the brothers' uncle, Roger I of Sicily, to increase his power.[33][34] Bohemond captured Bari in 1090[35][36] and before long, took control of most lands to the south of Melfi.[33]

First Crusade

In 1097, Bohemond and his uncle Roger I of Sicily were attacking Amalfi, which had revolted against Duke Roger, when bands of crusaders began to pass on their way through Italy to Constantinople. The zeal of the crusader came upon Bohemond; it is possible, however, that he saw in the First Crusade nothing more than a chance to carve for himself an eastern principality.[37] Geoffrey Malaterra bluntly states that Bohemond took the Cross with the intention of plundering and conquering Greek lands.

He gathered a Norman army, perhaps one of the finest in the crusading host, at the head of which he crossed the Adriatic Sea and penetrated to Constantinople along the route he had tried to follow in 1082–1084. He was careful to observe a "correct" attitude towards Alexius and, when he arrived at Constantinople in April 1097, did homage to the Emperor. He may have negotiated with Alexius about a principality at Antioch; if he did so, he had little encouragement. From Constantinople to Antioch, Bohemond was the real leader of the First Crusade. It says much for his leadership that the First Crusade succeeded in crossing Asia Minor, in which the Crusades of 1101, 1147 and the 1189 all failed.[37]

The Emperor's daughter, Anna Comnena, leaves a portrait of him in her Alexiad. She met him for the first time when she was fourteen and was seemingly fascinated by him, leaving no similar portrait of any other Crusader prince. Of Bohemond, she wrote:

Now [Bohemond] was such as, to put it briefly, had never before been seen in the land of the Romans [that is, Greeks], be he either of the barbarians or of the Greeks (for he was a marvel for the eyes to behold, and his reputation was terrifying). Let me describe the barbarian's appearance more particularly – he was so tall in stature that he overtopped the tallest by nearly one cubit, narrow in the waist and loins, with broad shoulders and a deep chest and powerful arms. And in the whole build of the body he was neither too slender nor overweighted with flesh, but perfectly proportioned and, one might say, built in conformity with the canon of Polycleitus... His skin all over his body was very white, and in his face the white was tempered with red. His hair was yellowish, but did not hang down to his waist like that of the other barbarians; for the man was not inordinately vain of his hair, but had it cut short to the ears. Whether his beard was reddish, or any other colour I cannot say, for the razor had passed over it very closely and left a surface smoother than chalk... His blue eyes indicated both a high spirit and dignity; and his nose and nostrils breathed in the air freely; his chest corresponded to his nostrils and by his nostrils...the breadth of his chest. For by his nostrils nature had given free passage for the high spirit which bubbled up from his heart. A certain charm hung about this man but was partly marred by a general air of the horrible... He was so made in mind and body that both courage and passion reared their crests within him and both inclined to war. His wit was manifold and crafty and able to find a way of escape in every emergency. In conversation he was well informed, and the answers he gave were quite irrefutable. This man who was of such a size and such a character was inferior to the Emperor alone in fortune and eloquence and in other gifts of nature.

A politique, Bohemond was resolved to engineer the enthusiasm of the crusaders to his own ends. When his nephew Tancred left the main army at Heraclea Cybistra and attempted to establish a footing in Cilicia, the movement may have been already intended as a preparation for Bohemond's eastern principality. Bohemond was the first to take up a position before Antioch (October 1097) and he played a considerable part in the siege, beating off the Muslim attempts to relieve the city from the east, and connecting the besiegers on the west with the Genoese ships which lay in the port of St Simeon.[37]

Through his connection with Firouz, one of the commanders in the city, Bohemond captured Antioch, although he did not press the siege until possession of the city was assured him in May 1098, and only then on learning of the approach of Kerbogha with a relief army. He held the city with a reservation in favour of Alexius, if Alexius should fulfill his promise to aid the crusaders. Bohemond was not secure in the possession of Antioch, though, even after its surrender and the defeat of Kerbogha; he had to make good his claims against Raymond of Toulouse, who championed the rights of Alexius. He obtained full possession in January 1099 and stayed near Antioch to secure his position, while the other crusaders moved south to the capture of Jerusalem.[37]

Bohemond came to Jerusalem at Christmas 1099, and had Dagobert of Pisa elected as Patriarch, perhaps in order to check the growth of Lotharingian power in the city. Whilst Bohemond had the fine territory, good strategic position and strong army necessary to found a principality in Antioch to dwarf Jerusalem, he had to face two great forces—the Byzantine Empire, which claimed the whole of his territories and was supported in its claim by Raymond of Toulouse, and the strong Muslim principalities in the north-east of Syria. Against these two forces he failed.[37]

Wars between Antioch and the Byzantine Empire

By 1100, the town of Malatia, which guarded one of the Cilician Gates through the Taurus Mountains, had been captured by an Armenian soldier of fortune. He received reports that the Malik Ghazi Danishmend (Danishmend Emir), Ghazi Gümüştekin of Sivas, was preparing an expedition to capture Malatia. The Armenians sought help from Bohemond.

Afraid to weaken his forces at Antioch, but not wishing to avoid the chance to extend his domain northwards, in August 1100 Bohemond marched north with only 300 knights and a small force of foot soldiers. Failing to send scouting parties, they were ambushed by the Turks and completely encircled at the Battle of Melitene. Bohemond managed to send one soldier to seek help from Baldwin of Edessa but was captured. He was laden with chains and imprisoned in Neo-Caesarea (modern Niksar) until 1103.

Alexius I was incensed that Bohemond had broken his sacred oath made in Constantinople and kept Antioch for himself. When he heard of Bohemond's capture, he offered to redeem the Norman commander for 260,000 dinars, if Ghazi Gumushtakin would hand the prisoner over to Byzantium. When Kilij Arslan I, the Seljuk overlord of the Emir, heard of the proposed payment threatened to attack unless given half the ransom. Bohemond proposed instead a ransom of 130,000 dinars paid just to the Emir. The bargain was concluded, and Ghazi and Bohemond exchanged oaths of friendship. Ransomed by Baldwin of Edessa, he returned in triumph to Antioch in August 1103.

His nephew Tancred had taken his uncle's place for three years. During that time, he had attacked the Byzantines, and had added Tarsus, Adana and Massissa in Cilicia to his uncle's territory; he was now deprived of his lordship by Bohemond's return. During the summer of 1103, the northern Franks attacked Ridwan of Aleppo to gain supplies and compelled him to pay tribute. Meanwhile, Raymond had established himself in Tripoli with the aid of Alexius, and was able to check the expansion of Antioch to the south. Early in 1104, Baldwin and Bohemond passed Aleppo to move eastward and attack Harran.

Whilst leading the campaign against Harran, Bohemond was defeated at Balak, near Rakka on the Euphrates (see Battle of Harran). The defeat was decisive, making impossible the great eastern principality which Bohemond had contemplated. It was followed by a Greek attack on Cilicia and, despairing of his own resources, Bohemond returned to Europe for reinforcements in late 1104.[37] It is a matter of historical debate whether his "crusade" against the Byzantine empire was to gain the backing and indulgences of Pope Paschal II. Either way, he enthralled audiences across France with gifts of relics from the Holy Land and tales of heroism while fighting the infidel, gathering a large army in the process. Henry I of England famously prevented him from landing on English shores, since the king anticipated Bohemond's great attraction to the English nobility. His newfound status won him the hand of Constance, daughter of the French king, Philip I. Of this marriage wrote Abbot Suger:

Bohemond came to France to seek by any means he could the hand of the Lord Louis' sister Constance, a young lady of excellent breeding, elegant appearance and beautiful face. So great was the reputation for valour of the French kingdom and of the Lord Louis that even the Saracens were terrified by the prospect of that marriage. She was not engaged since she had broken off her agreement to wed Hugh, count of Troyes, and wished to avoid another unsuitable match. The prince of Antioch was experienced and rich both in gifts and promises; he fully deserved the marriage, which was celebrated with great pomp by the bishop of Chartres in the presence of the king, the Lord Louis, and many archbishops, bishops and noblemen of the realm.

Bohemond and Constance produced a son, Bohemond II of Antioch.[38]

Encouraged by his success, Bohemond resolved to use his army of 34,000 men not to defend Antioch against the Greeks, but to attack Alexius.[39] Alexius, aided by the Venetians, proved too strong and Bohemond had to submit to a humiliating peace. Under the Treaty of Devol in 1108, he became the vassal of Alexius with the title of sebastos, consented to receive Alexius' pay, and promised to cede disputed territories and to admit a Greek patriarch into Antioch. Henceforth, Bohemond was a broken man. He died six months later without returning to the East,[40] and was buried at Canosa in Apulia, in 1111.[37]

Bohemond I in literature and media

The anonymous Gesta Francorum was written by one of Bohemond's followers. The Alexiad of Anna Comnena is a primary authority for the whole of his life.[37] A 1924 biography exists by Yewdale. See also the Gesta Tancredi by Ralph of Caen, which is a panegyric of Bohemond's second-in-command, Tancred. His career is discussed by B von Kügler, Bohemund und Tancred (1862); while L von Heinemann, Geschichte der Normannen in Sicilien und Unteritalien (1894), and R. Röhricht's Geschichte des ersten Kreuzzuges (1901) and Geschichte das Königreichs Jerusalem (1898) may also be consulted for his history.[37] The only major biography that exists in English is "Tancred : a study of his career and work in their relation to the First Crusade and the establishment of the Latin states in Syria and Palestine" by Robert Lawrence Nicholson. Details of his pre-crusade career can found in Geoffrey Malaterra's Deeds of Count Roger....

Count Bohemund by Alfred Duggan (1964) is an historical novel concerning the life of Bohemund and its events up to the fall of Jerusalem to the crusaders. Bohemond also appears in the historical novel Silver Leopard by F. Van Wyck Mason (1955), the short story "The Track of Bohemond" in the collection The Road of Azrael by Robert E. Howard (1979) and in the fantastical novel Pilgermann by Russell Hoban (1983).

The historical fiction novel Wine of Satan (1949) written by Laverne Gay gives an embellished accounting of the life of Bohemond.

See also

References

- ↑ Thomas Asbridge, The First Crusade, A New History, pp57-59

- ↑ God's War – Christopher Tyerman

- 1 2 Norwich 1992, p. 116.

- 1 2 3 Brown 2003, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (2016). "Bohemond II Prince of Antioch". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, pp. 116-117 (note 1), 227.

- ↑ Conti 1967, 24.

- 1 2 Norwich 1992, pp. 116-117 (note 1).

- ↑ Norwich 1992, pp. 116, 118.

- 1 2 Norwich 1992, p. 227.

- 1 2 Brown 2003, p. 143.

- 1 2 Norwich 1992, p. 195.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, pp. 195-196.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, p. 196.

- 1 2 3 4 Nicol 1992, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 Norwich 1992, p. 228.

- 1 2 Norwich 1992, pp. 231-232.

- ↑ Brown 2003, p. 166.

- ↑ Nicol 1992, pp. 57-58.

- 1 2 Norwich 1992, p. 233.

- 1 2 3 Nicol 1992, p. 58.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, p. 235.

- 1 2 3 Brown 2003, p. 170.

- 1 2 3 4 Norwich 1992, p. 243.

- 1 2 Norwich 1992, p. 245.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, p. 250.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, pp. 249-250.

- ↑ Brown 2003, p. 184.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, pp. 258-259.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, p. 261.

- 1 2 3 Brown 2003, p. 185.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, pp. 267-268.

- 1 2 Norwich 1992, p. 268.

- ↑ Brown 2003, p. 187.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, p. 269.

- ↑ Brown 2003, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Barker, Ernest (1911). "Bohemund". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 135–136.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Barker, Ernest (1911). "Bohemund". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 135–136. - ↑ Luscombe, Riley-Smith 2004, p. 760.

- ↑ W. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, 626

- ↑ Albert of Aix records his death at Bari (Albericus Aquensis II.XI, p. 177).

Sources

- Asbridge, Thomas (2000). The Creation of the Principality of Antioch, 1098-1130. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-661-3.

- Barber, Malcolm (2012). The Crusader States. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11312-9.

- Brown, Gordon S. (2003). The Norman Conquest of Southern Italy and Sicily. McFarland&Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-1472-7.

- Conti, Emanuele (1967). "L'abbazia della Matina (note storiche)". Archivio storico per la Calabria e la Lucania. 35: 11–30.

- Fink, Harold S. (1969). "The Growth of the Latin States, 1118-1144". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W. A History of the Crusades, Volume I: The First Hundred Years. The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 368–409. ISBN 0-299-04844-6.

- Luscombe, David; Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2004). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 4, C.1024-c.1198, Part II. Cambridge University Press.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42894-7.

- Norwich, John Julius (1992). The Normans in Sicily. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-015212-8.

- Runciman, Steven (1989a). A History of the Crusades, Volume I: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06161-X.

- Runciman, Steven (1989b). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06162-8.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02387-1.

- Yewdale, Ralph Bailey (1917). Bohemond I, Prince of Antioch (PhD thesis). Princeton University.

Further reading

- Ghisalberti, Albert M. (ed) Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Rome.

| New title | Prince of Taranto 1088–1111 |

Succeeded by Bohemond II |

| Prince of Antioch 1098–1111 | ||