Biafran airlift

The Biafran Airlift was an international humanitarian relief effort that transported food and medicine to Biafra during the 1967-70 secession war from Nigeria (Nigerian Civil War). It was the largest civilian airlift, and after the Berlin airlift of 1948-49, the largest non-combatant airlift of any kind ever carried out. The airlift was largely a series of joint efforts by Protestant and Catholic church groups, and other non-governmental organizations (NGO)s, operating civilian and military aircraft with volunteer (mostly) civilian crews and support personnel. Several national governments also supported the effort, mostly behind the scenes. This sustained joint effort, which lasted one and a half times as long as its Berlin predecessor, is estimated to have saved more than a million lives.[1]

Background

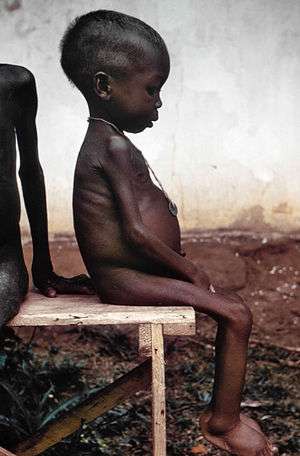

By 1968, a year after the start of the Nigerian Civil War, large numbers of children were reported starving to death due to a blockade imposed by the Federal Military Government (FMG) and military.[2] By 1969 it was reported that over 1,000 children per day were starving to death.[3] A FMG representative declared, “Starvation is a legitimate weapon of war, and we have every intention of using it.”[4] With the advent of global television reporting, for the first time, famine, starvation and humanitarian response were seen nightly on world television. People around the world demanded action.

International reaction to plight of the civilian population in the secessionist region was diverse. The United Nations and most national governments, expressing reluctance to become involved in what was officially considered an internal Nigerian affair, remained silent on the escalating humanitarian crisis. Secretary General of the United Nations, U Thant, refused to support the airlift.[5] The position of the Organization of African Unity was to not intervene in conflicts its members' deemed internal and to support the nation-state boundaries instituted during the colonial era.[6] The ruling Labour Party of the United Kingdom, which together with the USSR was supplying arms to the Nigerian military,[7] dismissed reports of famine as "enemy propaganda".[8] Mark Curtis writes that the UK also reportedly provided military assistance on the ‘neutralisation of the rebel airstrips’, with the understanding that their destruction would put them out of use for daylight humanitarian relief flights.[9]

The church-funded groups and NGOs became the most outspoken of the international supporters of aid to Biafra. The Joint Church Airlift provided relief aid as well as attempted to establish an air force for Biafra. This led to a ban by the Federal Military Government on aid flights into the region. The ICRC accepted the FMG’s ban and did not participate in any international publicity about Biafra, a position that was condemned by the more vocal and active NGOs providing aid. Bernard Kouchner, a French doctor and one of the more outspoken critics, declared that this silence over Biafra made the ICRC's workers ‘accomplices in the systematic massacre of a population’.[10]

American president Lyndon Johnson demanded his State Department "get those ... babies off my TV set”,[11][12] using a racial expletive. However, the US government began providing funding to relief efforts. By 1969 the US had sold eight C-97 military cargo aircraft to JCA and was reported to be providing 49% of all aid to the relief effort.[13]

Canada, facing its own internal separatist threat in the form of the Quebec sovereignty movement, was reluctant to extend aid to an area trying to separate from a fellow Commonwealth member, particularly in a region in which it had no prior experience. However, early assistance was provided with food, material and one military transport aircraft for several months. Financial assistance was also provided in the closing months of the airlift.[14]

France responded by providing aid to Biafra: humanitarian aid through the French Red Cross and military aid quietly, if not officially.[15]

While the vast majority of governments remained uninvolved, assistance was demanded by people around the world. Approximately 30 non-governmental organizations responded.[16]

The Airlift

Relief aid into Biafra began arriving by land, sea, and air soon after the start of the Nigerian Civil War in 1967. Reports of widespread famine began emerging, many from NGOs participating in the relief aid efforts. Relief flights ramped up after Nigeria's land and sea blockade of Biafra became near-total in June, 1968. These flights were mainly under the auspicies of the ICRC, with Nordchurchaid being a major donor/partner. Also in June 5, 1969[17] an ICRC DC-7 aircraft was shot down by Nigerian forces (killing 3 relief workers); Nigeria demanded all reflief flights be subject to their control; and the ICRC suspended their flights from Cotonou and Santa Isabelle.

A dispute arose between the NGOs and the ICRC over the latter's position to comply with Nigeria's demands for a ban on outside relief flights. The ICRC defended their position stating that "Article 23 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, intended for international armed conflict, stipulates that a belligerent State can satisfy itself that material assistance is neutral."[18][19]

A leading critic of the ICRC's position declared that their silence over Biafra made its workers accomplices in the systematic massacre of a population.[20] In response, the NGOs formally established their own relief flights operating out of Sao Tome. This was the effective start of Joint Church Aid, also referred to by media as "Jesus Christ Airlines," and what soon became known as the Biafran Airlift.

(Also in response to the ICRC's position, a group of French volunteer doctors working in Biafra concluded that a new aid organization that would prioritize the welfare of victims irrespective of national or religious boundaries was needed, went on to found Médecins Sans Frontières or Doctors Without Borders in 1971).

Relief flights landed at Uli, codenamed "Airstrip Annabelle", the only operational "airport" in Biafra. At the height of the airlift it became the second busiest airport in Africa after Johannesburg.[21] The bush landing strip was a widened road and had no instruments or navigation gear. The flights originated primarily from: the island of Sao Tome (then a Portuguese colony); the island of Fernando Po (then a Spanish colony and now known as Bioko, Republic of Equatorial Guinea); and Coutonou, Dahomey (now Benin).[22] The humanitarian airlift was undertaken almost exclusively by civilian cargo aircraft and without any escorting military or defensive aircraft. Flights were also made from Libreville, Gabon by the French who were supplying both relief aid and military supplies.

The flights were undertaken under cover of darkness and without lights to avoid attacking Nigerian aircraft who maintained air superiority during the day, supported by Soviet fishing trawlers offshore monitoring the flights.[23] Each aircraft made as many as four round-trips each night into Uli. The aircraft - nearly all of which were civilian and operated by civilian pilots - were based, fueled, repaired, and maintained at the supply end of the airlift, not in Biafra. Three were destroyed on the ground at Uli by Nigerian aircraft. Attacking aircraft were frequently nearby trying to catch the airlifters while landing or on the ground, forcing pilots to hover in darkness until an all-clear was sounded and runway lights could be activated barely long enough to enable a speedy landing. Separation between aircraft in the air was maintained by cockpit radio communication between pilots as there was no radar. Hostile aircraft were flown by mercenaries who taunted airlift pilots over the radio and used call signs such as "Genocide".[24] Approaches were made low over the treetops and landing was made without runway lights. At times the brief illumination of the runway lights could provide sufficient bearing for the attacking aircraft. Once on the ground Air and ground crew frequently had to evacuate the aircraft after landing and take cover from attacking aircraft in trenches alongside the runway. Radio broadcasts from Uli normally used code, such as “no landing lights” for “we are being bombed.”

Almost all of the airplanes, crews and logistics were paid, set up and maintained by the joint churches through contracted companies and volunteers on the ground. The largest aircraft, the C-97s, received major maintenance services performed by Israel Aircraft Industries volunteers working in Switzerland.[25][26]

By 1968 most of JCA's funding originated from the United States government and was funneled through JCA.[27]

At its peak in 1969, the airlift delivered an average of 250 metric tons of food each night to the estimated 1.5 to 2 million people dependent on food relief supplies, most of which was brought in by the airlift.[28] In late 1968, before the arrival of the C-97s from the USA, (VERIFY) an estimated 15-20 flights each night were made into Biafra: 10-12 from Sao Tome (JCA, Canairelief, and others), 6-8 from Fernando Po (mostly ICRC), and 3-4 from Libreville, Gabon (mostly French). This quantity of food was less than 10% of the amount needed to feed the estimated 2 million starving citizens.[29] In total over 5,300 missions were flown by JCA using ten different carriers, lifting 60,000 tons of humanitarian aid.[30]

Cargo involved more than just food. Some pilots agreed to carry cargo that could be hazardous to the aircraft: fuel for cooking and ground transport (flammable), and salt (corrosive).[31] On the return flights out of Uli, some flights carried materials for export sale. Others carried children, either orphans or in need of medical attention, said to be taken "far away in the sky".[32]

This airlift was the first major civilian airlift in history, and perhaps the largest of any civilian relief effort of any kind. Of the major participants, only OXFAM had any prior experience with field operations; Biafra was their second.[33] Pilots and some of the maintenance crews were perhaps the only trained persons involved. Most others were volunteers, performing tasks for which they had no little or no training or prior experience, from loading and unloading, warehouse, inventory, to aircraft maintenance and engine mechanics. The operating agencies were varied and often competing; many were also brand new to this type of effort. Organization and logistics were improved greatly through experience over months, with unloading times dropped from over 2 hours to 20 minutes per aircraft, often under attack or threat of attack.[34]

Aircraft and crews

Most of the aircraft were operated or contracted by "Joint Church Aid" (JCA), often referred to as "Jesus Christ Airlines" from the initials JCA, flying primarily from Sao Tome and Cotonou.

These were operated or provided by:

- Belair (Swiss-based airline under charter) flew former C-97s with volunteer American pilots and Transall C.160.[35]

- Canairelief - flew four purchased ex-Nordair Super Constellations.

- "Flight Test Research Inc." - ussell O'Quinn's company based in Long Beach, California, flew and with IAI maintained the four C-97G Stratofreighters sold by the U.S. government to "Joint Church Aid-USA" (one of them went into the night on May 8, lost in a crash landing in Biafra)

- "Flughjálp HF" - chartered by Nordchurchaid; based in Reykjavik, Iceland; established by Loftleidir, also known as Icelandic Airlines.

- "Transavia Holland NV" - provided five DC-6-B

- Fred. Olsen Airtransport was contracted and operated Douglas DC-6. One was bombed while unloading in Uli.[36]

- Independent contractors

The ICRC's operation flew primarily from Fermando Po. Flights were operated or provided by:

- Canadian Armed Forces - C-130 Hercules from Fernando Po on behalf of the ICRC.

- ICRC - 1967-1970

- Swedish & French Red Cross (C-130 Hercules)

Aircraft used were mostly aging multi-prop airliners such as DC-7s, DC-6s, DC-4s, DC3s, Avro Ansons, Lockheed Constellations, and Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellations. Aircraft registrations were removed from many aircraft due to the flights being declared illicit by the Federal Military Government and most of the international community. These were available at relatively low cost due to the rapidly increasing availability of the new generation of jet-powered passenger aircraft. Military transports Boeing C-97 Stratofreighters (sold by the US Government),[37] C-130E Hercules (from the Canadian Armed Forces),[38] and Transall C.160 (provided by Germany) were also loaned to the effort.

Airlift pilots came were from around the world: Australia, Canada, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, the United States, and elsewhere. One notable pilot was August Martin, the first African American commercial airline pilot and a former Tuskeegee Airman, who was killed when his plane crashed during the airlift.[39][40] Another was the Icelandic pilot Þorsteinn E. Jónsson.

At least 29 pilots and crew from the relief agencies were killed by accidents or by Nigerian forces in 10 separate incidents during the airlift: 25 from JCA, 4 from Canairelief, and 3 from ICRC.[41][42]

Contributors

Approximately 30 non-governmental organizations (NGO)s and several governments provided non-military direct and indirect aid through or in support of the Biafran Airlift. Major contributors of such items as food, medicine, transport aircraft, air and ground crew included:

- American Jewish Emergency Effort for Biafran Relief

- Canada (financial, food, material, C-130 Hercules aircraft)

- Canairrelief (a NGO organized by the Presbyterian Church of Canada and Oxfam Canada. Over 10,000 tons were carried in 674 flights)[43]

- Caritas Internationalis

- Church World Service

- Das Diakonische Werk (a German church group provided flight operations)[44]

- France

- Germany (one C.160 aircraft)

- Holy Ghost Airline (run by the Irish Catholic Holy Ghost Fathers, Africa Concern)

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) - also acting as an umbrella group for multiple national Red Cross agencies

- Nordchurchaid (an ad hoc organization of Protestant churched from Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden)

- Oxfam

- Portugal

- Save the Children Fund

- Sweden (C-130 Hercules aircraft) [45]

- UNICEF (contributed four field service officers)

- United States (financial, food, material, and eight C-97 US Air National Guard transport aircraft)

- World Council of Churches (WCC)

Others who contributed other non-humanitarian aid, such as military support and diplomatic recognition, are not included here. Countries and agencies who contributed solely or mostly through any of the above organizations are not listed separately.

Controversy

At the time and in the years since, the airlift has been the subject of controversy. The Nigerian government and some Nigerian military leaders stated the threat of genocide was fabricated and was "misguided humanitarian rubbish." They also said that mass starvation was an intended goal, saying "If the children must die first, then that is too bad, just too bad, ”[46] and "All is fair in war, and starvation is one of the weapons of war."[47] In a joint statement on August 16, 1968, the International Red Cross, UNICEF, World Council of Churches, and CARITAS stated: 'The conflict which concerned not hundred of thousands but millions of people was the greatest emergency it had handled since the Second World War.'[48] There have been accusations that the airlift supplied arms to Biafra, but these remain unsubstantiated.

Legacy

Whether mass starvation was intended or not, it became a fact and a legacy of the Nigerian Civil War. So too is the airlift. The images of children with bellies bloated from malnutrition remain an international historical symbol of Biafra, and it was these effects on the civilian population that inspired the airlift and whom the airlift benefitted. "Americans may not know much about Biafra, but they know about the children."[49] During that period, images of both the Biafran and the Vietnam wars were being broadcast daily around the world. The airlift's very existence was a potent example of the power of public opinion and an inspired civilian populace. Subsequent famine relief efforts in places such as Ethiopia, Somalia, or the former Yugoslavia by world governments were not met with the same response as with Biafra.

Notes

- ↑ Biafra Relief Heroes: remembering--in the words of those who were there..., Voice of Biafra International. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ Remembering the Nightmare of Biafra, The Free Library. Retrieved 2013-01-04

- ↑ New York Times, August 24, 1969. Retrieved 2013-01-04

- ↑ Philip Gourevitch, Alms Dealers, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ Roy Thomas, The Birth of CANAIRELIEF, Vanguard Magazine, September 2006. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ Sixties in America Archived February 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 2013-01-11

- ↑ BBC, on this day in history, 1969: Nigeria bans Red Cross aid to Biafra

- ↑ Secret papers reveal Biafra intrigue, BBC News, January 3, 2000. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ Nigeria's War Over Biafra, 1967-70, Mark Curtis. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ Biafra and the Birth of the new Humanitarianism. Retrieved 2013-01-05

- ↑ Cohen & Tucker, page 275 Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ Philip Gourevitch, Alms Dealers, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ New York Times, July 21, 1969. Retrieved 2012-01-04

- ↑ Roy Thomas, The Birth of CANAIRELIEF, Vanguard Magazine, September 2006. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ The Tragedy of Biafra: A Report by the American Jewish Congress, December 1968. Retrieved 2013-01-11

- ↑ Humanitarian Aid and the Biafra War: Lessons not Learned, Africa Development, Vol. XXXIV, No. 1, 2009, Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2009. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ Godwin Alabi-Isama, The Tragedy of Victory, Ibadan, 2013. page 385-393

- ↑ The International Committee of the Red Cross and humanitarian assistance - A policy analysis 31-10-1996. Retrieved 2013-01-12

- ↑ Doctors Without Borders, THE MSF EXPERIENCE, by Rony Brauman and Joelle Tanguy (1998) Archived April 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 2013-01-13

- ↑ Biafra and the Birth of the ‘New Humanitarianism’, Far Outliers, 23 August 2006. Retrieved 2013-01-12

- ↑ Koren, page 256.

- ↑ The Lost American, Fred Cuny. Frontline, PBS. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ Biafra: A People Betrayed, Kurt Vonnegut, 1979. Retrieved 2013-01-13

- ↑ The Biafran airlift by NGOs faced federal mercenaries in the skies, Look and Learn, December 1973. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ The Full Story of the Secret Biafra Air Rescue. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ Biafran Airlift: Israel's Secret Mission to Save Lives. Retrieved 2013-11-24

- ↑ David L. Koren: The World Is Deep, Biafran Airlift, Friends of Nigeria. Archived November 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ Nigeria's War Over Biafra, 1967-70, Mark Curtis. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ The Tragedy of Biafra: A Report by the American Jewish Congress, December 1968. Retrieved 2013-01-11

- ↑ Roy Thomas, The Birth of CANAIRELIEF, Vanguard Magazine, September 2006. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ M. Lawrence Kurtz, in Koren, pp 305-307.

- ↑ BORN TO SERVE: The biography of Dr. Akanu Ibiam, by D. C. Nwafor. Retrieved 2013-01-05

- ↑ Biafra and the Birth of the ‘New Humanitarianism’, Far Outliers, 23 August 2006. Retrieved 2013-01-12

- ↑ Humanitarian Aid and the Biafra War: Lessons not Learned, Africa Development, Vol. XXXIV, No. 1, 2009, Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2009. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ Civil War in Nigeria (Biafra), 1967-70. Tom Cooper Nov 13, 2003.

- ↑ Sundby, Jon (1993). A/S Fred. Olsens Flyselskap 60 år (in Norwegian). Bærum: Fred. Olsens Flyveselskap. p. 42.

- ↑ The Full Story of the Secret Biafra Air Rescue. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ Roy Thomas, The Birth of CANAIRELIEF, Vanguard Magazine, September 2006. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ One of the first Black Airline Pilots, AvStop.com. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ Koren, David L. p.168.

- ↑ Sean Maloney, Where's Biafra?, Macleans Magazine, July 16, 2008. Retrieved 2013-01-02

- ↑ Biafra Relief Heroes: remembering--in the words of those who were there..., Voice of Biafra International. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ Roy Thomas, The Birth of CANAIRELIEF, Vanguard Magazine, September 2006. Retrieved 2013-01-03c

- ↑ David L. Koren: The World Is Deep, Biafran Airlift, Friends of Nigeria. Archived November 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2013-01-03

- ↑ C130Hercules.net. Retrieved 2013-01-12

- ↑ Nigerian Colonel Atakunie, (London Economist, Aug. 24, 1968 as cited in the Village Voice Oct. 17, 1968; and San_Francisco_Chronicle, July 2) as cited in Village Voice Oct. 17, 1968. Cited in The Tragedy of Biafra, A Report by the American Jewish Congress December 1968, page 24. Retrieved 2013-01-12

- ↑ Atrributed to Chief Awolowo and Chief Allison Ayida, in There was a country: Blockade, starvation and a requiem for Biafra, The Nation, October 23, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13

- ↑ BORN TO SERVE: The biography of Dr. Akanu Ibiam by D. C. Nwafor.. Retrieved 2013-01-06

- ↑ Biafra: A People Betrayed, Kurt Vonnegut, 1979. Retrieved 2013-01-13

References

- Cohen, Warren I. and Tucker, Nancy Bernkopf (editors): Lyndon Johnson Confronts the World: American Foreign Policy 1963-1968. Cambridge University Press 1994. ISBN 0-521-41428-8

- Koren, David L.: Far Away in the Sky: A Memoir of the Biafran Airlift. David L. Koren, 2011. ISBN 1467996149

- Schwab, Peter: Biafra, Facts on File (1971). ISBN 087196192X

- Chinua Achebe: There Was A Country: A Personal History of Biafra (Penguin, New York, 2012). ISBN 978-1-59420-482-1

- N.U. Akpan The Struggle for Secession 1966-1970: A personal account of the Nigerian civil war (Frank Kass and Co., London, 1972). ISBN 0-7146-2930-8

- Elechi Amadi: Sunset in Biafra: A Civil War Diary (Heinemann, African Writers Series, London, 1973). ASIN B000NPB7EU

- Andrew Brewin and David MacDonald: Canada and the Biafran Tragedy (James Lewis & Samuel, Toronto, 1970). ISBN 0888620071

- Michael I. Draper: Shadows: Airlift and Airwar in Biafra and Nigeria 1967-1970 (Hikoki Publications, London, 2000). ISBN 978-1902109633

- Frederick Forsyth: The Making of an African Legend: The Biafra Story (Penguin, London, 1969, republished 1977). ISBN 1902109635

- John de St. Jorre The Nigerian Civil War (Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1972). ISBN 978-0340126400

- Biafra: Random Thoughts of C. Odumegwu Ojukwu, General of the People's Army (Harper & Row, London, 1969). ASIN B0007G6D9E

- Bengt Sundkler, Christopher Steed: A History of the Church in Africa. Cambridge University Press (2000). ISBN 052158342X

External links

- The Tragedy of Biafra: A Report by the American Jewish Congress, December 1968

- David L. Koren: The World Is Deep, Biafran Airlift, Friends of Nigeria.

- David L. Koren: Far Away in the Sky: A Memoir of the Biafran Airlift

- Humanitarian Aid and the Biafra War: Lessons not Learned, Africa Development, Vol. XXXIV, No. 1, 2009, pp. 69–82, Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2009 (ISSN 0850-3907)

- Catholic Herald, November 8, 1968

- ACOA Nigeria-Biafra Relief Memo #4, American Committee on Africa, November 1, 1968

- Nigerian Civil War, US Department of State Archives, Foreign Relations, 1969-1976, Volume E-5, Documents on Africa, 1969-1972