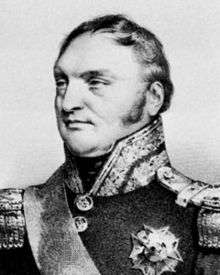

Bertrand Clausel

Bertrand, comte Clausel (or Clauzel) (12 December 1772 – 21 April 1842) was a marshal of France.

Military career

Bertrand Clausel was born on 12 December 1772 at Mirepoix in the County of Foix, and served in the first campaign of the French Revolutionary Wars as one of the volunteers of 1791.[1]

In June 1795, having distinguished himself repeatedly in the war on the northern frontier (1792–1793) and the fighting in the eastern Pyrénées (1793–1794), Clausel was made a general of brigade. In this rank he served in Italy in 1798 and 1799, and in the disastrous campaign of the latter year he won great distinction at the battles of the Trebbia and of Novi. In 1802 he served in the expedition to San Domingo. He became a general of division in December 1802, and after his return to France he was in almost continuous military employment there until in 1806 he was sent to the army of Naples. Soon after this Napoleon made him a grand officer of the Legion of Honor. In 1808–1809 he was with Marmont in Dalmatia, and at the close of 1809 he was appointed to a command in the army of Portugal under Masséna.[1]

Peninsular campaigns of 1810 and 1811

Clausel took part in the Peninsular campaigns of 1810 and 1811, including the Torres Vedras campaign, and under Marmont he did excellent service in re-establishing the discipline, efficiency and mobility of the army, which had suffered severely in the retreat from Torres Vedras. In the Salamanca campaign (1812) the result of Clausels work was shown in the marching powers of the French, and at the battle of Salamanca, Clausel, who had succeeded to the command when Marmont was wounded, and had himself received a severe wound, drew off his army with the greatest skill. The retreat on Burgos was conducted by him so well that the pursuers failed to make the slightest impression, and had themselves in the end to retire from the siege of Burgos (1812).[1]

Commander of the Army

Early in 1813 Clausel was made commander of the Army of the North in Spain, but he was unable to avert the great disaster of Vitoria. Under the supreme command of Soult he served through the rest of the Peninsular War with unvarying distinction. On the first restoration in 1814 he submitted unwillingly to the Bourbons, and when Napoleon returned to France, he hastened to join him. During the Hundred Days he was in command of an army defending the Pyrenean frontier. Even after Waterloo he long refused to recognize the restored government, and he escaped to America, being condemned to death in absence.[1] He then settled in the Vine and Olive Colony in Alabama, later returning to France after the failure of that venture.

Political life

He took the first opportunity of returning to aid the Orléanist Liberals in France (1820), sat in the Chamber of deputies from 1827 to 1830, and after the July Revolution of 1830 was at once given a military command. Clausel replaced the Legitimist General de Bourmont in charge of the invasion of Algeria. He made a successful campaign, but he was soon recalled by the home government, which desired to avoid complications in Algeria. At the same time he was made a Marshal of France (February 1831). For some four years thereafter he urged his Algerian policy upon the Chamber of deputies, and finally in 1835 was reappointed commander-in-chief. But after several victories, including the taking of Mascara in 1835, the Marshal met with a severe repulse at Constantine in 1836.[1]

A change of government in France was primarily responsible for the failure, but public opinion attributed it to Clausel, who was recalled in February 1837. He thereupon retired from active service, and, after vigorously defending his conduct before the deputies, he ceased to take part in public affairs. He lived in complete retirement up to his death at Secourrieu (Garonne).[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Clausel, Bertrand, Count". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 466.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Clausel, Bertrand, Count". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 466.