Bell's spaceship paradox

Bell's spaceship paradox is a thought experiment in special relativity. It was first designed by E. Dewan and M. Beran in 1959[1] and became more widely known when J. S. Bell included a modified version.[2] A delicate string or thread hangs between two spaceships. Both spaceships now start accelerating simultaneously and equally as measured in the inertial frame S, thus having the same velocity at all times in S. Therefore, they are all subject to the same Lorentz contraction, so the entire assembly seems to be equally contracted in the S frame with respect to the length at the start. Therefore, at first sight, it might appear that the thread will not break during acceleration.

This argument, however, is incorrect as shown by Dewan & Beran and Bell.[1][2] The distance between the spaceships does not undergo Lorentz contraction with respect to the distance at the start, because in S, it is effectively defined to remain the same, due to the equal and simultaneous acceleration of both spaceships in S. It also turns out that the rest length between the two has increased in the frames in which they are momentarily at rest (S′), because the accelerations of the spaceships are not simultaneous here due to relativity of simultaneity. The thread, on the other hand, being a physical object held together by electrostatic forces, maintains the same rest length. Thus, in frame S, it must be Lorentz contracted, which result can also be derived when the electromagnetic fields of bodies in motion are considered. So, calculations made in both frames show that the thread will break; in S′ due to the non-simultaneous acceleration and the increasing distance between the spaceships, and in S due to length contraction of the thread.

In the following, the rest length[3] or proper length[4] of an object is its length measured in the object's rest frame. (This length corresponds to the proper distance between two events in the special case, when these events are measured simultaneously at the endpoints in the object's rest frame.[4])

Dewan and Beran

Dewan and Beran stated the thought experiment by writing:

- "Consider two identically constructed rockets at rest in an inertial frame S. Let them face the same direction and be situated one behind the other. If we suppose that at a prearranged time both rockets are simultaneously (with respect to S) fired up, then their velocities with respect to S are always equal throughout the remainder of the experiment (even though they are functions of time). This means, by definition, that with respect to S the distance between the two rockets does not change even when they speed up to relativistic velocities."[1]

Then this setup is repeated again, but this time the back of the first rocket is connected with the front of the second rocket by a silk thread. They concluded:

- "According to the special theory the thread must contract with respect to S because it has a velocity with respect to S. However, since the rockets maintain a constant distance apart with respect to S, the thread (which we have assumed to be taut at the start) cannot contract: therefore a stress must form until for high enough velocities the thread finally reaches its elastic limit and breaks."[1]

Dewan and Beran also discussed the result from the viewpoint of inertial frames momentarily comoving with the first rocket, by applying a Lorentz transformation:

- "Since , (..) each frame used here has a different synchronization scheme because of the factor. It can be shown that as increases, the front rocket will not only appear to be a larger distance from the back rocket with respect to an instantaneous inertial frame, but also to have started at an earlier time."[1]

They concluded:

- "One may conclude that whenever a body is constrained to move in such a way that all parts of it have the same acceleration with respect to an inertial frame (or, alternatively, in such a way that with respect to an inertial frame its dimensions are fixed, and there is no rotation), then such a body must in general experience relativistic stresses."[1]

Then they discussed the objection, that there should be no difference between a) the distance between two ends of a connected rod, and b) the distance between two unconnected objects which move with the same velocity with respect to an inertial frame. Dewan and Beran removed those objections by arguing:

- Since the rockets are constructed exactly the same way, and starting at the same moment in S with the same acceleration, they must have the same velocity all of the time in S. Thus they are traveling the same distances in S, so their mutual distance cannot change in this frame. Otherwise, if the distance were to contract in S, then this would imply different velocities of the rockets in this frame as well, which contradicts the initial assumption of equal construction and acceleration.

- They also argued that there indeed is a difference between a) and b): Case a) is the ordinary case of length contraction, based on the concept of the rod's rest length l0 in S0, which always stays the same as long as the rod can be seen as rigid. Under those circumstances, the rod is contracted in S. But the distance cannot be seen as rigid in case b) because it is increasing due to unequal accelerations in S0, and the rockets would have to exchange information with each other and adjust their velocities in order to compensate for this – all of those complications don't arise in case a).

Bell

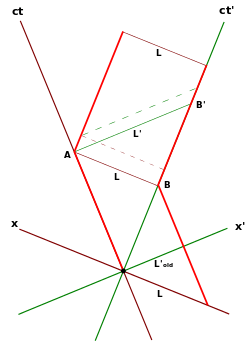

In Bell's version of the thought experiment, three spaceships A, B and C are initially at rest in a common inertial reference frame, B and C being equidistant to A. Then, a signal is sent from A to reach B and C simultaneously, causing B and C starting to accelerate in the vertical direction (having been pre-programmed with identical acceleration profiles), while A stays at rest in its original reference frame. According to Bell, this implies that B and C (as seen in A's rest frame) "will have at every moment the same velocity, and so remain displaced one from the other by a fixed distance." Now, if a fragile thread is tied between B and C, it's not long enough anymore due to length contractions, thus it will break. He concluded that "the artificial prevention of the natural contraction imposes intolerable stress".[2]

Bell reported that he encountered much skepticism from "a distinguished experimentalist" when he presented the paradox. To attempt to resolve the dispute, an informal and non-systematic survey of opinion at CERN was held. According to Bell, there was "clear consensus" which asserted, incorrectly, that the string would not break. Bell goes on to add,

- "Of course, many people who get the wrong answer at first get the right answer on further reflection. Usually they feel obliged to work out how things look to observers B or C. They find that B, for example, see C drifting further and further behind, so that a given piece of thread can no longer span the distance. It is only after working this out, and perhaps only with a residual feeling of unease, that such people finally accept a conclusion which is perfectly trivial in terms of A's account of things, including the Fitzgerald contraction."

Importance of length contraction

In general, it was concluded by Dewan & Beran and Bell, that relativistic stresses arise when all parts of an object are accelerated the same way with respect to an inertial frame, and that length contraction has real physical consequences. For instance, Bell argued that the length contraction of objects as well as the lack of length contraction between objects in frame S can be explained using relativistic electromagnetism. The distorted electromagnetic intermolecular fields cause moving objects to contract, or to become stressed if hindered from doing so. In contrast, no such forces act on the space between objects.[2] (Generally, Richard Feynman demonstrated how the Lorentz transformation can be derived from the case of the potential of a charge moving with constant velocity (as represented by the Liénard–Wiechert potential). As to the historical aspect, Feynman alluded to the circumstance that Hendrik Lorentz arrived essentially the same way at the Lorentz transformation,[5] see also History of Lorentz transformations.)

However, Petkov (2009)[6] and Franklin (2009)[3] interpret this paradox differently. They agreed with the result that the string will break due to unequal accelerations in the rocket frames, which causes the rest length between them to increase (see the Minkowski diagram in the analysis section). However, they denied the idea that those stresses are caused by length contraction in S. This is because, in their opinion, length contraction has no "physical reality", but is merely the result of a Lorentz transformation, i.e. a rotation in four-dimensional space which by itself can never cause any stress at all. Thus the occurrence of such stresses in all reference frames including S and the breaking of the string is supposed to be the effect of relativistic acceleration alone.[3][6]

Discussions and publications

Paul Nawrocki (1962) gives three arguments why the string should not break,[7] while Edmond Dewan (1963) showed in a reply that his original analysis still remains valid.[8] Many years later and after Bell's book, Matsuda and Kinoshita reported receiving much criticism after publishing an article on their independently rediscovered version of the paradox in a Japanese journal. Matsuda and Kinoshita do not cite specific papers, however, stating only that these objections were written in Japanese.[9]

However, in most publications it is agreed that stresses arise in the string, with some reformulations, modifications and different scenarios, such as by Evett & Wangsness (1960),[10] Dewan (1963),[8] Romain (1963),[11] Evett (1972),[12] Gershtein & Logunov (1998),[13] Tartaglia & Ruggiero (2003),[14] Cornwell (2005),[15] Flores (2005),[16] Semay (2006),[17] Styer (2007),[18] Freund (2008),[19] Redzic (2008),[20] Peregoudov (2009),[21] Redžić (2009),[22] Gu (2009),[23] Petkov (2009),[6] Franklin (2009),[3] Miller (2010),[24] Fernflores (2011),[25] Kassner (2012).[26] A similar problem was also discussed in relation to angular accelerations: Grøn (1979),[27] MacGregor (1981),[28] Grøn (1982, 2003).[29][30]

Analysis

Rotating disc

Bell's spaceship paradox is not about preserving the rest length between objects (as in Born rigidity), but about preserving the distance in an inertial frame relative to which the objects are in motion, for which the Ehrenfest paradox is an example.[26] Historically, Albert Einstein had already recognized in the course of his development of general relativity, that the circumference of a rotating disc is measured to be larger in the corotating frame than the one measured in an inertial frame.[30] Einstein explained in 1916:[31]

- "We suppose that the circumference and diameter of a circle have been measured with a standard measuring rod infinitely small compared with the radius, and that we have the quotient of the two results. If this experiment were performed with measuring rods at rest relatively to the Galilean system K′, the quotient would be π. With measuring rods at rest relatively to K, the quotient would be greater than π. This is readily understood if we envisage the whole process of measuring from the "stationary" system K′, and take into consideration that the measuring rods applied to the periphery undergoes a Lorentz contraction, while the ones applied along the radius do not. Hence Euclidean geometry does not apply to K."

As pointed out more precisely by Einstein in 1919, the relation is given[30]

- ,

being the circumference in the corotating frame, in the laboratory frame, is the Lorentz factor . Therefore, it's impossible to bring a disc from the state of rest into rotation in a Born rigid manner. Instead, stresses arise during the phase of accelerated rotation, until the disc enters the state of uniform rotation.[30]

Accelerating ships

Similarly, in the case of Bell's spaceship paradox the relation between the initial rest length between the ships (identical to the moving length in S after acceleration) and the new rest length in S′ after acceleration, is:[3][6][8][16]

- .

This length increase can be calculated in different ways. For instance, if the acceleration is finished the ships will constantly remain at the same location in the final rest frame S′, so it's only necessary to compute the distance between the x-coordinates transformed from S to S′. If and are the ships' positions in S, the positions in their new rest frame S′ are:[3]

Another method was shown by Dewan (1963) who demonstrated the importance of relativity of simultaneity.[8] The perspective of frame S′ is described, in which both ships will be at rest after the acceleration is finished. The ships are accelerating simultaneously at in S (assuming acceleration in infinitesimal small time), though B is accelerating and stopping in S′ before A due to relativity of simultaneity, with the time difference:

Since the ships are moving with the same velocity in S′ before acceleration, the initial rest length in S is shortened in S′ by due to length contraction. This distance starts to increase after B came to stop, because A is now moving away from B with constant velocity during until A stops as well. Dewan arrived at the relation (in different notation):[8]

It was also noted by several authors that the constant length in S and the increased length in S′ is consistent with the length contraction formula , because the initial rest length is increased by in S′, which is contracted in S by the same factor, so it stays the same in S:[6][14][18]

Summarizing: While the rest distance between the ships increases to in S′, the relativity principle requires that the string (whose physical constitution is unaltered) maintains its rest length in its new rest system S′. Therefore, it breaks in S′ due to the increasing distance between the ships. As explained above, the same is also obtained by only considering the start frame S using length contraction of the string (or the contraction of its moving molecular fields) while the distance between the ships stays the same due to equal acceleration.

Born rigidity

The mathematical treatment of this paradox is similar to the treatment of Born rigid motion. However, rather than ask about the separation of spaceships with the same acceleration in an inertial frame, the problem of Born rigid motion asks, "What acceleration profile is required by the second spaceship so that the distance between the spaceships remains constant in their proper frame?"[32][33] In order for the two spaceships, initially at rest in an inertial frame, to maintain a constant proper distance, the lead spaceship must have a lower proper acceleration.[3][33][34]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dewan, Edmond M.; Beran, Michael J. (March 20, 1959). "Note on stress effects due to relativistic contraction". American Journal of Physics. American Association of Physics Teachers. 27 (7): 517–518. Bibcode:1959AmJPh..27..517D. doi:10.1119/1.1996214.

- 1 2 3 4 Bell, John Stewart (1987). Speakable and unspeakable in quantum mechanics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52338-9. in chapter 9 of his popular 1976 book on quantum mechanics.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Franklin, Jerrold (2010). "Lorentz contraction, Bell's spaceships, and rigid body motion in special relativity". European Journal of Physics. 31 (2): 291–298. arXiv:0906.1919

. Bibcode:2010EJPh...31..291F. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/31/2/006.

. Bibcode:2010EJPh...31..291F. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/31/2/006. - 1 2 Moses Fayngold (2009). Special Relativity and How it Works. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 3527406077.: p. 407: "Note that the proper distance between two events is generally not the same as the proper length of an object whose end points happen to be respectively coincident with these events. Consider a solid rod of constant proper length l(0). If you are in the rest frame K0 of the rod, and you want to measure its length, you can do it by first marking its end-points. And it is not necessary that you mark them simultaneously in K0. You can mark one end now (at a moment t1) and the other end later (at a moment t2) in K0, and then quietly measure the distance between the marks. We can even consider such measurement as a possible operational definition of proper length. From the viewpoint of the experimental physics, the requirement that the marks be made simultaneously is redundant for a stationary object with constant shape and size, and can in this case be dropped from such definition. Since the rod is stationary in K0, the distance between the marks is the proper length of the rod regardless of the time lapse between the two markings. On the other hand, it is not the proper distance between the marking events if the marks are not made simultaneously in K0."

- ↑ Feynman, R.P. (1970), "21–6. The potentials for a charge moving with constant velocity; the Lorentz formula", The Feynman Lectures on Physics, 2, Reading: Addison Wesley Longman, ISBN 0-201-02115-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vesselin Petkov (2009): Accelerating spaceships paradox and physical meaning of length contraction, arXiv:0903.5128, published in: Veselin Petkov (2009). Relativity and the Nature of Spacetime. Springer. ISBN 3642019625.

- ↑ Nawrocki, Paul J. (October 1962). "Stress Effects due to Relativistic Contraction". American Journal of Physics. 30 (10): 771–772. Bibcode:1962AmJPh..30..771N. doi:10.1119/1.1941785.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dewan, Edmond M. (May 1963). "Stress Effects due to Lorentz Contraction". American Journal of Physics. 31 (5): 383–386. Bibcode:1963AmJPh..31..383D. doi:10.1119/1.1969514. (Note that this reference also contains the first presentation of the ladder paradox.)

- ↑ Matsuda, Takuya & Kinoshita, Atsuya (2004). "A Paradox of Two Space Ships in Special Relativity". AAPPS Bulletin. February: ?. eprint version

- ↑ Evett, Arthur A.; Wangsness, Roald K. (1960). "Note on the Separation of Relativistically Moving Rockets". American Journal of Physics. 28 (6): 566–566. Bibcode:1960AmJPh..28..566E. doi:10.1119/1.1935893.

- ↑ Romain, Jacques E. (1963). "A Geometrical Approach to Relativistic Paradoxes". American Journal of Physics. 31 (8): 576–585. Bibcode:1963AmJPh..31..576R. doi:10.1119/1.1969686.

- ↑ Evett, Arthur A. (1972). "A Relativistic Rocket Discussion Problem". American Journal of Physics. 40 (8): 1170–1171. Bibcode:1972AmJPh..40.1170E. doi:10.1119/1.1986781.

- ↑ Gershtein, S. S.; Logunov, A. A. (1998). "J. S. Bell's problem". Physics of Particles and Nuclei. 29 (5): 463–468. Bibcode:1998PPN....29..463G. doi:10.1134/1.953086.

- 1 2 Tartaglia, A.; Ruggiero, M. L. (2003). "Lorentz contraction and accelerated systems". European Journal of Physics. 24 (2): 215–220. arXiv:gr-qc/0301050

. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/24/2/361.

. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/24/2/361. - ↑ Cornwell, D. T. (2005). "Forces due to contraction on a cord spanning between two spaceships". EPL (Europhysics Letters). 71 (5): 699–704. Bibcode:2005EL.....71..699C. doi:10.1209/epl/i2005-10143-x.

- 1 2 Flores, Francisco J. (2005). "Bell's spaceships: a useful relativistic paradox". Physics Education. 40 (6): 500–503. Bibcode:2005PhyEd..40..500F. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/40/6/F03.

- ↑ Semay, Claude (2006). "Observer with a constant proper acceleration". European Journal of Physics. 27 (5): 1157–1167. arXiv:physics/0601179

. Bibcode:2006EJPh...27.1157S. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/27/5/015.

. Bibcode:2006EJPh...27.1157S. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/27/5/015. - 1 2 Styer, Daniel F. (2007). "How do two moving clocks fall out of sync? A tale of trucks, threads, and twins". American Journal of Physics. 75 (9): 805–814. Bibcode:2007AmJPh..75..805S. doi:10.1119/1.2733691.

- ↑ Jürgen Freund (2008). "The Rocket-Rope Paradox (Bell's Paradox)". Special Relativity for Beginners: A Textbook for Undergraduates. World Scientific. pp. 109–116. ISBN 981277159X.

- ↑ Redžić, Dragan V. (2008). "Note on Dewan Beran Bell's spaceship problem". European Journal of Physics. 29 (3): N11–N19. Bibcode:2008EJPh...29...11R. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/29/3/N02.

- ↑ Peregoudov, D. V. (2009). "Comment on 'Note on Dewan-Beran-Bell's spaceship problem'". European Journal of Physics. 30 (1): L3–L5. Bibcode:2009EJPh...30L...3P. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/30/1/L02.

- ↑ Redžić, Dragan V. (2009). "Reply to 'Comment on "Note on Dewan-Beran-Bell's spaceship problem"'". European Journal of Physics. 30 (1): L7–L9. Bibcode:2009EJPh...30L...7R. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/30/1/L03.

- ↑ Gu, Ying-Qiu (2009). "Some Paradoxes in Special Relativity and the Resolutions". Advances in Applied Clifford Algebras. 21 (1): 103–119. arXiv:0902.2032

. doi:10.1007/s00006-010-0244-6.

. doi:10.1007/s00006-010-0244-6. - ↑ Miller, D. J. (2010). "A constructive approach to the special theory of relativity". American Journal of Physics. 78 (6): 633–638. arXiv:0907.0902

. Bibcode:2010AmJPh..78..633M. doi:10.1119/1.3298908.

. Bibcode:2010AmJPh..78..633M. doi:10.1119/1.3298908. - ↑ Fernflores, Francisco (2011). "Bell's Spaceships Problem and the Foundations of Special Relativity". International Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 25 (4): 351–370. doi:10.1080/02698595.2011.623364.

- 1 2 Kassner, Klaus (2011). "Spatial geometry of the rotating disk and its non-rotating counterpart". American Journal of Physics. 80 (9): 772–781. arXiv:1109.2488

. Bibcode:2012AmJPh..80..772K. doi:10.1119/1.4730925.

. Bibcode:2012AmJPh..80..772K. doi:10.1119/1.4730925. - ↑ Grøn, Ø. (1979). "Relativistic description of a rotating disk with angular acceleration". Foundations of Physics. 9 (5-6): 353–369. Bibcode:1979FoPh....9..353G. doi:10.1007/BF00708527.

- ↑ MacGregor, M. H. (1981). "Do Dewan-Beran relativistic stresses actually exist?". Lettere al Nuovo Cimento. 30 (14): 417–420. doi:10.1007/BF02817127.

- ↑ Grøn, Ø. (1982). "Energy considerations in connection with a relativistic rotating ring". American Journal of Physics. 50 (12): 1144–1145. Bibcode:1982AmJPh..50.1144G. doi:10.1119/1.12918.

- 1 2 3 4 Øyvind Grøn (2004). "Space Geometry in a Rotating Reference Frame: A Historical Appraisal" (PDF). In G. Rizzi; M. Ruggiero. Relativity in Rotating Frames. Springer. ISBN 1402018053.

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (1916). "Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie" (PDF). Annalen der Physik. 49: 769–782. Bibcode:1916AnP...354..769E. doi:10.1002/andp.19163540702.. See English translation.

- ↑ Misner, Charles; Thorne, Kip S. & Wheeler, John Archibald (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. p. 165. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- 1 2 Nikolić, Hrvoje (6 April 1999). "Relativistic contraction of an accelerated rod". American Journal of Physics. American Association of Physics Teachers. 67 (11): 1007–1012. arXiv:physics/9810017

. Bibcode:1999AmJPh..67.1007N. doi:10.1119/1.19161.

. Bibcode:1999AmJPh..67.1007N. doi:10.1119/1.19161. - ↑ Mathpages: Born Rigidity and Acceleration

External links

- Michael Weiss, Bell's Spaceship Paradox (1995), USENET Relativity FAQ