Battle of the Barrier Forts

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

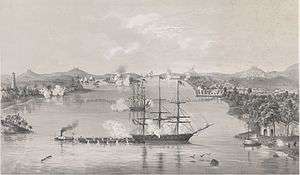

The Battle of the Barrier Forts (also known as the Battle of the Pearl River Forts) was fought between American and Chinese forces in the Pearl River, Guangdong, China in November 1856 during the Second Opium War. The United States Navy launched an amphibious assault against a series of four forts known as the Barrier Forts forts near the city of Canton (modern-day Guangzhou). It was considered an important battle by the British whose interest lay in capturing Canton.

Background

Sailing off the Chinese coast, USS Portsmouth and USS Levant had received news of the beginning of the Second Opium War. The two sloops-of-war were tasked with protecting American lives by landing a 150-man detachment of marines and sailors in Canton.

After a peaceful landing the Americans occupied the ancient city. Commanded by both Commodore James Armstrong and Captain Henry H. Bell, USS San Jacinto arrived in Canton's harbor and learned of the occupation. San Jacinto then landed a shore party of her own.

On November 15, 1856, after a brief stay and no military contact, the force withdrew from the city. During the withdrawal, Commander Andrew H. Foote of the Portsmouth rowed out to his ship. As he rowed past the Pearl River Forts, the Chinese garrison fired on the small American boat a few times but the withdrawal continued.

The next day the U.S. seamen had constructed a plan to attack Canton's citadels in retaliation for the Chinese attack on Commander Foote.

Battle

Now a force of one steam frigate and two sloops-of-war, the naval squadron under James Armstrong made their way up the Pearl River and launched an attack on Canton's coastal forts. USS Portsmouth closed in on the nearest of the four citadels and fired the initial salvo on November 16.

For two hours her bombardment continued until the Chinese batteries were silenced. After this first engagement, Chinese and American officials decided to try to settle the matter diplomatically. This failed and on November 20, Commodore Armstrong ordered his ships to fire again on two more of the Chinese forts.

This bombardment lasted until the Chinese batteries weakened slightly, after which the Levant, commanded by William N. Smith, received 22 cannonball shots in her sails, rigging, and hull. Under cover of their ships' fire, a storming party of 287 troops led by Foote landed unopposed. Spearheading this force were about 50 marines under Captain John D. Simms and a small detachment of sailors.[3][4] They quickly captured the first enemy fort, then used its 53 guns to attack and capture the second fort.

When taking the second position, the Chinese launched several counterattacks with some 3,000 Qing Army soldiers from Canton. In a few more days of intense combat until November 24, the U.S. force, with help from the blockade, pushed back the attacking Chinese army, killing and wounding dozens of the attackers, capturing two more forts and spiking 176 enemy guns.

Chinese casualties were an estimated 250 to 500 killed or wounded. The Americans land forces sustained seven killed and 22 wounded. USS Levant suffered one dead and six wounded in her exchange with the Pearl River Forts. Portsmouth was hit 18 times and the Levant 22 times, but neither was seriously damaged.[5]

Aftermath

After James Armstrong's attack on the Chinese fortifications, diplomatic efforts began again and the American and Chinese governments signed an agreement for U.S. neutrality in the Second Opium War. This ended the United States' participation in the conflict until 1859, when Commodore Josiah Tattnall in the chartered steamship Towey Wan participated in the Battle of Taku Forts, which was ultimately unsuccessful. In 1857, the British and French would use Pearl River to attack Canton from water, resulting in the Battle of Canton. America's opening of Asia continued into the 1860s with conflict, such as the Battle of Shimonoseki Straits and a following bombardment, as well as an expedition to Korea in the 1870s.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 McClellan, Edwin North (September 1920). "The Capture of the Barrier Forts in the Canton River, China". Marine Corps Gazette 5 (3): 262–276.

- ↑ Hoppin, James Mason (1874). Life of Andrew Hull Foote, Rear-Admiral United States Navy. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 120.

- ↑ Bernard C. Nalty (1962). The Barrier Forts: A Battle, a Monument, and a Mythical Marine Archived September 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.. Washington D.C.: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. p. 6.

- ↑ Clark, George B. (2001). Treading Softly: U.S. Marines in China, 1819-1949. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 8.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (2013). Almanac of American Military History. Volume 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 782. ISBN 978-1-59884-530-3.

References

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- Bartlett, Beatrice S. Monarchs and Ministers: The Grand Council in Mid-Ch'ing China, 1723–1820. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991.

- Ebrey, Patricia. Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993.

- Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59 (2000): 603-46.

- Fauré, David. Emperor and Ancestor: State and Lineage in South China. 2007.

- "China", Encyclopædia Britannica, 1944, v. 5, pp. 536–537;

- William L. Langer, An Encyclopedia of World History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948), p. 879.

- Foote to Armstrong, 4 Nov 1856, East India Squadron Letters, 1855–1856, National Archives;

- Clyde H. Metcalf, "History of the U. S. Marine Corps" (New York: Putnam, 1939), pp. 172–173;

- H. A. Ellsworth, "One Hundred Eighty Landings of U. S. Marines" (Washington: Historical Section, HQMC, 1934), pp. 24–25;

- Charles O. Paullin, "Early Voyages of American Naval Vessels to the Orient", "U. S. Naval Institute Proceedings", v. 37, no. 2 (Jun 1911), pp. 391–396.

- Typed extracts, log of SAN JACINTO, 16 Nov 1856, Archives, HQMC.

- Typed extracts, log of PORTSMOUTH, 16 Nov 1856, Archives, HQMC.

- Foote to Armstrong, 26 Nov 1856, East India Squadron Letters.

- "Ibid.;" Simms to CMC, 7 Dec 1856, Historical File, Marines, National Archives.

- Typed extracts, log of the PORTSMOUTH; Foote to Armstrong, 5 Dec 1856, East India Squadron Letters.

- Wood, William Maxwell (1859). Fankwei; or, the San Jacinto in the Seas of India, China and Japan. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 415–469.