Battle of St. Quentin (1557)

| Battle of St. Quentin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian War of 1551–1559 | |||||||

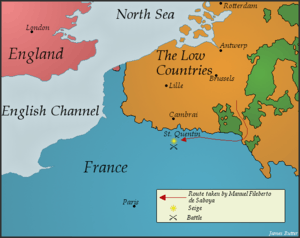

Map of Manuel Fileberto de Saboya's Dutch campaign. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 60,000[4]-80,000[4] | 26,000[5] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,000, or as few as 57[6] | 3,000 killed and 7,000 captured[4] or 14,000[5] or 15,000 casualties,[lower-alpha 1] 16 cannons, 50 flags and 60 banners[6] | ||||||

The Battle of Saint-Quentin of 1557 was fought at Saint-Quentin in Picardy, during the Italian War of 1551–1559. The Spanish, which is to say the international forces[7] of Philip II's Spanish Empire, who had regained the support of the English whose Mary I of England he had married, won a significant victory over the French at Saint-Quentin, in northern France.[8]

Battle

The battle took place on the Feast Day of St. Lawrence (10 August). Spain, now under the rule of Philip II, was allied with England following Philip's marriage to the queen of England, Mary I. Mary had declared war on France, 7 June 1557.[9]

At the Battle of St. Quentin the French forces under Constable Anne de Montmorency were overwhelmed, and Montmorency was captured by the forces under the command of the Duke Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy and the Count of Egmont in an alliance with English troops, and the French were defeated.[9] During the fighting the Saint-Quentin collegiate church was badly damaged by fire.[10]

After the victory over the French at St. Quentin, "the sight of the battlefield gave Philip a permanent distaste for war";[11] he declined to pursue his advantage, withdrawing to the Spanish Netherlands to the north,[1] where he had been the Governor since 1555. The Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis ended the war two years later.

Feast of Saint Lawrence

Being of a grave religious bent, Philip II was aware that 10 August is the Feast of St Lawrence, a Roman deacon who was roasted on a gridiron for his Christian beliefs. Hence, in commemoration of the great victory on St Lawrence’s Day, Philip sent orders to Spain that a great palace in the shape of a gridiron should be built in the Guadarrama Mountains northwest of Madrid. Known as El Escorial, it was finally completed in 1584.

Impact

The greatest impact of this battle was not on France, England or Spain, but on Italy. Duke Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy, having won the victory, had also secured a place at the conference table when the terms of peace were deliberated, resulting in the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, 1559. The duke was able to secure the independence of the Duchy of Savoy, which had been occupied by the French a generation earlier. As part of the peace terms, Emmanuel Philibert married Marguerite d’Angoulême, younger sister of King Henry II of France, in 1559. The Duke of Savoy moved his capital across the Alps to Turin two years later, making Savoy an Italian state and refounding the dynasty of the House of Savoy, which would become the royal house of a united Italy in 1860.

References

- ↑ According to Federico Fernández San Román, the French army lost 6,000 foot soldiers, 3,000 horse soldiers, 300 gentlemen and 10 knights of the Royal service killed, plus 6,000 prisoners, among them 10 colonels and 30 captains. San Román, 1863, p. 84.

- 1 2 A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol. II, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010), 518.

- ↑ Berenger, Jean: A History of the Habsburg Empire 1273-1700. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2014. ISBN 1317895703, p. 213

- ↑ Potter, David: Renaissance France at War: Armies, Culture and Society, C.1480-1560. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 2008. ISBN 1843834057, p. 12

- 1 2 3 Continuing the 'Auld Alliance' in the Sixteenth Century, E.A. Bonner, The Scottish Soldier Abroad, 1247-1967, ed. Grant G. Simpson, (Rowman & Littlefield, 1992), 35.

- 1 2 Nolan, Cathal J.: The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000-1650: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Vol. 2. London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006, ISBN 9780313337345, p. 756

- 1 2 Fernández San Román, Federico: Batalla de San Quintín. Madrid: Vicente y Lavajos, 1863, p. 84

- ↑ Henry Kamen, Philip of Spain (1997) gives a brief account based on contemporary sources, noting that Spanish troops constistuted about 10% of the Habsburg total. Kamen claims that the battle was "won by a mainly Netherlandish army commanded by the non-Spaniards the duke of Savoy and the earl of Egmont". Kamen, Henry: Golden Age Spain. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 023080246X, p. 28. On the other hand, Geoffrey Parker states that Spanish troops were decisive in defeating the French at St. Quentin owing to their high value, as well as in defeating the Ottomans at Hungary in 1532 and at Tunis in 1535, and the German protestants at Mühlberg in 1547. Parker, Geoffrey: España y la rebelión de Flandes. Madrid: Nerea, 1989. ISBN 8486763266, p. 41

- ↑ Henning von Koss, 1914. "Die Schlachten bei St. Quentin (10. August 1557) und bei Gravelingen (13. Juli 1558)", Historische Studien vol. 118. xvi+161 pp, 2 plates Ebering, Berlin. (Reprint 1965, Kraus Reprint (Vaduz).

- 1 2 Habsburg and Valois, Stanley Leathes, The Cambridge Modern History, Volume 10, ed. Sir Adolphus William Ward, (Cambridge University Press, 1907), 92.

- ↑ "Basilique Saint-Quentin". Orgues en France. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol. 9, (William Benton and Helen Hemingway Benton, 1992), 377.

Coordinates: 49°50′55″N 3°17′11″E / 49.8486°N 3.2864°E