Battle of Mogadishu (1993)

| Battle of Mogadishu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Gothic Serpent and the Somali Civil War | |||||||

CW3 Michael Durant's helicopter Super Six-Four above Mogadishu on 3 October 1993. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Al-Qaeda[2] | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Initially: 160 men 12 vehicles (9 Humvees, 3 M939 trucks) 19 aircraft (16 helicopters – 8 Black Hawks and 8 Little Birds) | 4,000–6,000 militiamen and civilian fighters | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

U.S. 18 killed, 73 wounded, 1 captured[3][4] Malaysia 1 killed, 7 wounded Pakistan 1 killed, 2 wounded |

SNA Militia and civilians 200–315 killed (per ICRC)[5][6] 300–500 killed (per U.N.)[7] 315 killed (133 militiamen), 812 wounded (per SNA)[6][8] 350 killed, 500 wounded (per U.S.)[7] 500 killed (per neutral Somalis)[7] | ||||||

| |||||||

The Battle of Mogadishu or Day of the Rangers (Somali: Maalintii Rangers), was part of Operation Gothic Serpent and was fought from 3–4 October 1993, in Mogadishu, Somalia, between forces of the United States, supported by UNOSOM II, and Somali militiamen loyal to the self-proclaimed president-to-be Mohamed Farrah Aidid, who had support from armed civilian fighters. The battle is also referred to as the First Battle of Mogadishu to distinguish it from subsequent battles in that city, such as the Second Battle of Mogadishu of 2006.

The initial U.S. Joint Special Operations force, Task Force Ranger, was a collaboration of various elite special forces units from Army Special Operations Command, Air Force Special Operations Command and Navy Special Warfare Command. Task Force Ranger was dispatched to seize two of Aidid's high-echelon lieutenants during a meeting in the city. The goal of the operation was achieved, though conditions spiraled into the deadly Battle of Mogadishu. The initial operation of 3 October 1993, intended to last an hour, became an overnight standoff and rescue operation extending into daylight hours of 4 October.

Summary

Task Force Ranger was created in August 1993, and deployed to Somalia in September. Task Force Ranger consisted of various elite special operations units from Army, Air Force and Navy special services: U.S. Army Rangers from Bravo Company, 3rd Battalion 75th Ranger Regiment; C Squadron, 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (1st SFOD-D), better known as "Delta Force"; helicopters flown by 1st Battalion, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment; Air Force Combat Controllers; Air Force Pararescuemen; and Navy SEALs. As a multi-disciplinary joint special forces operation, Task Force Ranger reported to Joint Special Operations Command, led by Major General William F. Garrison.

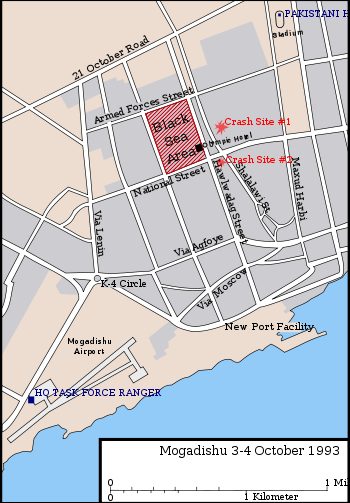

On 3 October 1993, Task Force Ranger began an operation that involved traveling from their compound on the city's outskirts to the center with the aim of capturing the leaders of the Habr Gidr clan, led by Mohamed Farrah Aidid. The assault force consisted of nineteen aircraft, twelve vehicles (including nine Humvees), and 160 men. The operation was intended to last no more than an hour.

Shortly after the assault began, Somali militia and armed civilian fighters shot down two UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters. The subsequent operation to secure and recover the crews of both helicopters extended the initial operation into an overnight standoff and daylight rescue operation on 4 October. The battle resulted in 18 deaths, 73 wounded, and one helicopter pilot captured among the U.S. raid party and rescue forces. At least one Pakistani soldier and one Malaysian soldier were killed as part of the rescue forces on day two of the battle. American sources estimate between 1,500 and 3,000 Somali casualties, including civilians; the Somali National Alliance (SNA) claims 315 dead, with 812 wounded.

During the operation, two U.S. Black Hawk helicopters were shot down by RPGs and three others were damaged. Some of the wounded survivors were able to evacuate to the compound, but others remained near the crash sites and were isolated. An urban battle ensued and continued throughout the night.

Early the next morning, a combined task force was sent to rescue the trapped soldiers. It contained soldiers from the Pakistan Army, the Malaysian Army and the U.S. Army's 10th Mountain Division. They assembled over one hundred vehicles, including Pakistani tanks (M48s) and Malaysian Condor armoured personnel carriers and were supported by U.S. MH-6 Little Bird and MH-60L Black Hawk helicopters. This task force reached the first crash site and rescued the survivors. The second crash site had been overrun by hostile Somalis during the night. Delta snipers Gary Gordon and Randy Shughart volunteered to hold them off until ground forces arrived. A Somali mob with thousands of combatants eventually overran the two men. That site's lone surviving American, pilot Michael Durant, had been taken prisoner but was later released.

The exact number of Somali casualties is unknown, but estimates range from several hundred to over a thousand militiamen and others killed,[10][11] with injuries to another 3,000–4,000.[12] The International Committee of the Red Cross estimated 200 Somali civilians killed and several hundred wounded in the fighting,[13] with reports that some civilians attacked the Americans.[14] The book Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War estimates more than 700 Somali militiamen dead and more than 1,000 wounded, but the Somali National Alliance in a Frontline documentary on American television acknowledged only 133 killed in the whole battle.[15] The Somali casualties were reported in The Washington Post as 312 killed and 814 wounded.[4] The Pentagon initially reported five American soldiers were killed,[16] but the toll was actually 18 American soldiers dead and 73 wounded. Two days later, a 19th soldier, Delta operator SFC Matt Rierson, was killed in a mortar attack. Among U.N. forces, one Malaysian and one Pakistani died; seven Malaysians and two Pakistanis were wounded. At the time, the battle was the bloodiest involving U.S. troops since the Vietnam War and remained so until the Second Battle of Fallujah in 2004.

On 24 July 1996, Aidid was wounded during a firefight between his militia and forces loyal to former Aidid allies, Ali Mahdi Muhammad and Osman Ali Atto. He suffered a fatal heart attack on 1 August 1996, either during or after surgery to treat his wounds.[17] The following day, General Garrison retired.[18]

Background

In January 1991, Somalian President Mohammed Siad Barre was overthrown in the ensuing civil war by a coalition of opposing clans.[19] The Somali National Army concurrently disbanded and some former soldiers reconstituted as irregular regional forces or joined the clan militias.[20] The main rebel group in the capital Mogadishu was the United Somali Congress (USC),[19] which later divided into two armed factions: one led by Ali Mahdi Muhammad, who became president, and the other by Mohamed Farrah Aidid. In total, there were four opposition groups that competed for political control – the USC, Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM) and Somali Democratic Movement (SDM). In June 1991, a ceasefire was agreed to, but failed to hold. A fifth group, the Somali National Movement (SNM), later declared independence in the Somalia's northwest portion in June. The SNM renamed the unrecognized territory Somaliland, with its leader Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur selected as president.[21]

In September 1991, severe fighting broke out in Mogadishu, which continued in the following months and spread throughout the country, with over 20,000 people killed or injured by the end of the year. These wars led to the destruction of Somalia's agriculture, which in turn led to starvation in large parts of the country. The international community began to send food supplies to halt the starvation, but vast amounts of food were hijacked and brought to local clan leaders, who routinely exchanged it with other countries for weapons. An estimated 80 percent of the food was stolen. These factors led to even more starvation, from which an estimated 300,000 people died and another 1.5 million people suffered between 1991 and 1992. In July 1992, after a ceasefire between the opposing clan factions, the U.N. sent 50 military observers to watch the food's distribution.[21]

Operation Provide Relief began in August 1992, when the U.S. President George H. W. Bush announced that U.S. military transports would support the multinational U.N. relief effort in Somalia. Ten C-130s and 400 people were deployed to Mombasa, Kenya, airlifting aid to Somalia's remote areas and reducing reliance on truck convoys. The C-130s delivered 48,000 tons of food and medical supplies in six months to international humanitarian organizations trying to help Somalia's more than three million starving people.[21]

When this proved inadequate to stop the massive death and displacement of the Somali people (500,000 dead and 1.5 million refugees or displaced), the U.S launched a major coalition operation to assist and protect humanitarian activities in December 1992. This operation, called Operation Restore Hope, saw the U.S. assuming the unified command in accordance with Resolution 794. The U.S. Marine Corps landed the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit in Mogadishu and, with elements of 1st Battalion, 7th Marines and 3rd Battalion, 11th Marines, secured nearly one-third of the city, the port, and airport facilities within two weeks, with the intent to facilitate airlifted humanitarian supplies. Elements of the 2nd Battalion; HMLA-369 (Helicopter Marine Light Assault-369 of Marine Aircraft Group-39, 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, Camp Pendleton); 9th Marines; and 1st Battalion, 7th Marines quickly secured routes to Baidoa, Balidogle and Kismayo, then were reinforced by the 3rd Assault Amphibian Battalion and the U.S. Army's 10th Mountain Division.[21]

Mission shift

On 3 March 1993, the U.N. Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali submitted to the U.N. Security Council his recommendations for effecting the transition from UNITAF to UNOSOM II. He indicated that since Resolution 794's adoption in December 1992, UNITAF's presence and operations had created a positive impact on Somalia's security situation and on the effective delivery of humanitarian assistance (UNITAF deployed 37,000 personnel over forty percent of southern and central Somalia). There was still no effective government, police, or national army with the result of serious security threats to U.N. personnel. To that end, the Security Council authorized UNOSOM II to establish a secure environment throughout Somalia, to achieve national reconciliation so as to create a democratic state.[21][22]

At the Conference on National Reconciliation in Somalia, held on 15 March 1993, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, all fifteen Somali parties agreed to the terms set out to restore peace and democracy. Yet, by May it became clear that, although a signatory to the March Agreement, Mohammed Farrah Aidid's faction would not cooperate in the Agreement's implementation.[21]

Aidid began to broadcast anti-U.N. propaganda on Radio Mogadishu after believing that the U.N. was purposefully marginalizing him in an attempt to "rebuild Somalia". Lieutenant General Çevik Bir ordered the radio station shut down, in an attempt to quash the beginning of what could turn into a rebellion. Civilian spies throughout UNOSOM II's headquarters likely led to the uncovering of the U.N.'s plan. Aidid ordered SNA militia to attack a Pakistani force on 5 June 1993, that had been tasked with the inspection of an arms cache located at the radio station, possibly out of fear that this was a task force sent to shut down the broadcast. The result was 24 dead, and 57 wounded Pakistani troops, as well as 1 wounded Italian and 3 wounded American soldiers. On 6 June 1993, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 837, for the arrest and prosecution of the persons responsible for the death and wounding of the peacekeepers.[23]

On 12 June, U.S. troops started attacking targets in Mogadishu in hopes of finding Aidid, a campaign which lasted until 16 June. On 17 June, a $25,000 warrant was issued by Admiral Jonathan Howe for information leading to Aidid's arrest, but he was never captured.[24] Howe also requested a rescue force after the Pakistanis' deaths.

Attack on safe house

On 12 July 1993, a U.S.-led operation was launched on what was believed to be a safe house where Aidid was hiding in Mogadishu. During the 17-minute combat operation, U.S. Cobra attack helicopters fired 16 TOW missiles and thousands of 20-millimeter cannon rounds into the compound, killing 60 people. The number of Somali fatalities was disputed. Abdi Qeybdiid, Aidid's interior minister, claimed 73 dead, including women and children who had been in the safe house. The reports Jonathan Howe got after the attack placed the number of dead at 20, all men. The International Committee of the Red Cross set the number of dead at 54.[25] Aidid was not present.

The operation would lead to the deaths of four journalists – Dan Eldon, Hos Maina, Hansi Kraus and Anthony Macharia – who were killed by angry Mogadishu mobs when they arrived to cover the incident,[26] which presaged the Battle of Mogadishu.[27]

Some believe that this American attack was a turning point in unifying Somalis against U.S. efforts in Somalia, including former moderates and those opposed to the Habar Gidir.[28][29]

Task Force Ranger

On 8 August 1993, Aidid's militia detonated a remote controlled bomb against a U.S. military vehicle, killing four soldiers. Two weeks later another bomb injured seven more.[30] In response, U.S. President Bill Clinton approved the proposal to deploy a special task force composed of elite special forces units, including 400 U.S. Army Rangers and Delta Force operators.[31]

On 22 August, the unit deployed to Somalia under the command of Major General William F. Garrison, commander of the special multi-disciplinary Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) at the time.

The force consisted of:

- B Company, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment

- C Squadron, 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (1st SFOD-D)

- A deployment package of 16 helicopters and personnel from the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (160th SOAR), which included MH-60 Black Hawks and AH/MH-6 Little Birds.

- Navy SEALs from the Naval Special Warfare Development Group (DEVGRU)

- Air Force Pararescuemen and Combat Controllers from the 24th Special Tactics Squadron.[32]

On 21 September, Task Force Ranger captured Aidid's financier, Osman Ali Atto.

First Black Hawk shot down

At around 02:00 on 25 September, Aidid's men shot down a 101st Airborne Division Black Hawk with an RPG and killed three crew members at New Port near Mogadishu. The shootdown was a huge SNA psychological victory.[33][34]

Order of Battle

U.S. and UNOSOM

Units involved in the battle:

- Task Force Ranger, including :

- C Squadron, 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (1st SFOD-D) – aka "Delta Force"[35]

- Bravo Company, 3rd Ranger Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment[35]

- 1st Battalion, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne) (The Night Stalkers) with MH-6J and AH-6 "Little Birds" and MH-60 A/L Black Hawks[35]

- Combat Controllers and Pararescuemen from the 24th Special Tactics Squadron[36]

- Navy SEALs from the Naval Special Warfare Development Group (DEVGRU)

- CVN-72 USS Abraham Lincoln & Carrier Air Wing 11[37]

- Task Force-10th Mountain Division,[35] including:

- 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment,

- 3rd platoon, C Company, 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment[38]

- 15th Battalion, of the Frontier Force Regiment, Pakistan Army[39]

- 19th Lancers of the Pakistan Army[39]

- 10th Battalion, of the Baloch Regiment of Pakistan Army.

- Included with the TF was the 977 MP Co.

- U.N. Forces

- 19th Battalion, Royal Malay Regiment of the Malaysian Army[40]

- 11th Regiment, Grup Gerak Khas (few GGK operators during rescue the Super 6-1 crews)[40]

- 7th Battalion, Frontier Force Regiment of the Pakistan Army[41]

USC/SNA

The size and organizational structure of the Somali militia forces involved in the battle are not known in detail. In all, between 2,000–4,000 regular faction members are believed to have participated, almost all of whom belonged to Aidid's Somali National Alliance. They drew largely from his Habar Gidir Hawiye clan, who battled U.S. troops starting 12 July 1993.[42]

The Somali National Alliance (SNA) was formed 14 August 1992. It began as the United Somali Congress (USC) under Aidid's leadership. At the time of Operation Gothic Serpent, the SNA was composed of Col. Omar Gess' Somali Patriotic Movement, the Somali Democratic Movement, the combined Digil and Mirifleh clans, the Habr Gedir of the United Somali Congress headed by Aidid, and the newly established Southern Somali National Movement.

After formation, the SNA immediately staged an assault against the militia of the Hawadle Hawiye clan, who controlled the Mogadishu port area. As a result, the Hawadle Hawiye were pushed out of the area, and Aidid's forces took control.[43]

Battle Proper

- See Timeline of the Battle of Mogadishu for a detailed chronology from a U.S. Army perspective

Plan

On Sunday – 3 October 1993, Task Force Ranger, U.S. special operations forces composed mainly of Bravo Company 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (better known as "Delta Force") operators, and the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne) ("The Night Stalkers"), attempted to capture Aidid's foreign minister Omar Salad Elmi and his top political advisor, Mohamed Hassan Awale.[44]

The plan was that Delta operators would assault the target building (using MH-6 Little Bird helicopters) and secure the targets inside the building while four Ranger chalks (under CPT Michael D. Steele's command) would fast rope down from hovering MH-60L Black Hawk helicopters. The Rangers would then create a four-corner defensive perimeter around the building while a column of nine HMMWVs and three M939 five-ton trucks (under LTC Danny McKnight's command) would arrive at the building to take the entire assault team and their prisoners back to base. The entire operation was estimated to take no longer than 30 minutes.[45]

The ground-extraction convoy was supposed to reach the captive targets a few minutes after the operation's beginning, but it ran into delays. Somali citizens and local militia formed barricades along Mogadishu's streets with rocks, wreckage, rubbish and burning tires, blocking the convoy from reaching the Rangers and their captives. Aidid militiamen with megaphones were shouting, "Kasoobaxa guryaha oo iska celsa cadowga!" ("Come out and defend your homes!").[46]

Raid

At 13:50, Task Force Ranger analysts received intelligence of Salad's location.

At 15:42, the MH-6 assault Little Birds carrying the Delta operators hit the target, the wave of dust becoming so bad that one was forced to go around again and land out of position. Next, the two Black Hawks carrying the second Delta assault team came into position and dropped their teams as the four Ranger chalks prepared to rope onto the four corners surrounding the target building. Chalk Four being carried by Black Hawk callsign Super 67, piloted by CW3 Jeff Niklaus, was accidentally put a block north of their intended point. Declining the pilot's offer to move them back down due to the time it would take to do so, leaving the helicopter too exposed, Chalk Four intended to move down to the planned position, but intense ground fire prevented them from doing so.

The ground convoy arrived ten minutes later near the Olympic Hotel and waited for Delta and Rangers to complete their mission (target building).

During the operation's first moments, Ranger PFC Todd Blackburn, from Chalk Four, fell while fast-roping from his Black Hawk Super 67 while it was hovering 70 feet (21 m) above the streets. Blackburn suffered an injury to his head and back of his neck and required evacuation by SGT Jeff Struecker's column of three Humvees. While taking PFC Todd Blackburn back to base, SGT Dominick Pilla, assigned to SGT Struecker's Humvee, was killed instantly when a bullet entered his head.[47] When SGT Struecker's Humvee column reached the base and safety, all three vehicles were riddled with bullet holes and smoking.[46]

At about 16:20, one of the Black Hawk helicopters, callsign Super 61 piloted by CW3 Cliff "Elvis" Wolcott and CW3 Donovan Briley, was shot down by an RPG. Both pilots were killed in the resulting crash and two of the crew chiefs were severely wounded. SSG Daniel Busch and SGT Jim Smith, both Delta snipers, survived the crash and began defending the site.

An MH-6, callsign Star 41 and piloted by CW3 Karl Maier and CW5 Keith Jones, landed nearby and Jones left the helicopter and carried Busch to the safety of the helicopter while Maier provided cover fire from the Little Bird's cockpit, repeatedly denying orders to lift off while his co-pilot was not in the Bird. He nearly hit Chalk One's LT DiTomasso arriving with Rangers and Delta operators to secure the site. Jones and Maier evacuated SSG Busch and SGT Smith, though SSG Busch later died of his injuries, being shot four times while defending the crash site.

A Combat Search and Rescue (CSAR) team, led by Air Force Pararescueman TSgt Scott Fales, were able to fast rope down to Super 61's crash site despite an RPG hit that crippled their helicopter, Super 68, piloted by CW3 Dan Jollota. Despite the damage, Super 68 did make it back to base. The CSAR team found both the pilots dead and two wounded inside the crashed helicopter. Under intense fire, the team moved the wounded men to a nearby collection point, where they built a makeshift shelter using Kevlar armor plates salvaged from Super 61's wreckage.[48]

There was confusion between the ground convoy and the assault team. The assault team and the ground convoy waited for 20 minutes to receive their orders to move out. Both units were under the mistaken impression that they were to be first contacted by the other. During the wait, a second Black Hawk helicopter, callsign Super 64 and piloted by CW3 Michael Durant, was shot down by an RPG-7 at around 16:40.[49]

Most of the assault team went to the first crash site for a rescue operation. Upon reaching the site, about 90 Rangers and Delta Force operators found themselves under heavy fire. Despite air support, the assault team was effectively trapped for the night. With a growing number of wounded needing shelter, they occupied several nearby houses and confined the occupants for the battle's duration.[50] Outside, a stiff breeze stirred up blinding, brown clouds of dust.

At the second crash site, two Delta snipers, MSG Gary Gordon and SFC Randy Shughart, were inserted by Black Hawk Super 62 – piloted by CW3 Mike Goffena. Their first two requests to be inserted were denied, but they were finally granted permission upon their third request. They inflicted heavy casualties on the approaching Somali mob. Super 62 had kept up their fire support for MSG Gordon and SFC Shughart, but an RPG struck Super 62. Despite the damage, Super 62 managed to go to the New Port and safety. When MSG Gordon was eventually killed, SFC Shughart picked up Gordon's CAR-15 and gave it to Super 64 pilot CW3 Michael Durant. SFC Shughart went back around the helicopter's nose and held off the mob for about 10 more minutes before he was killed. The Somalis then overran the crash site and killed all but Durant. He was nearly beaten to death, but was saved when members of Aidid's militia came to take him prisoner.[49] For their actions, MSG Gordon and SFC Shughart were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the first awarded since the Vietnam War.[35]

Repeated attempts by the Somalis to mass forces and overrun the American positions in a series of firefights near the first crash site were neutralized by aggressive small arms fire and by strafing runs and rocket attacks from AH-6J Little Bird helicopter gunships of the Nightstalkers, the only air unit equipped and trained for night fighting.

A relief convoy with elements from the Task Force 2–14 Infantry, 10th Mountain Division, accompanied by Malaysian and Pakistani U.N. forces, arrived at the first crash site at around 02:00. No contingency planning or coordination with U.N. forces had been arranged prior to the operation; consequently, the recovery of the surrounded American troops was significantly complicated and delayed. Determined to protect all of the rescue convoy's members, General Garrison made sure that the convoy would roll out in force. When the convoy finally pushed into the city, it consisted of more than 100 U.N. vehicles including Malaysian forces' German-made Condor APCs, four Pakistani tanks (M48s), American Humvees and several M939 five-ton flatbed trucks. This two-mile-long column was supported by several other Black Hawks and Cobra assault helicopters stationed with the 10th Mountain Division. Meanwhile, Task Force Ranger's "Little Birds" continued their defense of Super 61's downed crew and rescuers. The American assault force sustained heavy casualties, including several killed, and a Malaysian soldier died when an RPG hit his Condor vehicle. Seven Malaysians and two Pakistanis were wounded.[40][41]

Mogadishu Mile

The battle was over by 06:30 on Monday, 4 October. U.S. forces were finally evacuated to the U.N. base by the armored convoy. While leaving the crash site, a group of Rangers and Delta operators led by SSG. John R. Dycus realized that there was no room left in the vehicles for them and were forced to depart the city on foot to a rendezvous point on National Street. This has been commonly referred to as the "Mogadishu Mile". U.S. forces suffered one casualty during the mile, Sgt. Randal J. Ramaglia, after he was hit by a bullet in the back, and successfully evacuated.[51]

In all, 18 U.S. soldiers were killed in action during the battle and another 73 were wounded in action.[52] The Malaysian forces lost one soldier and had seven injured, while the Pakistanis suffered two injured. Somali casualties were heavy, with estimates on fatalities ranging from 315[6] to over 2,000 combatants. The Somali casualties were a mixture of militiamen and local civilians. Somali civilians suffered heavy casualties due to the dense urban character of that portion of Mogadishu. Two days later, a mortar round fell on the U.S. compound, killing one U.S. soldier, SFC Matt Rierson, and injuring another twelve. A team on special mission to Durant's Super 64 helicopter had 2 wounded, Boxerman and James on 6 October.[53]

Two weeks after the battle, General Garrison officially accepted responsibility. In a handwritten letter to President Clinton, Garrison took full responsibility for the battle's outcome. He wrote that Task Force Ranger had adequate intelligence for the mission and that their objective (capturing targets from the Olympic Hotel) was met.[54]

Aftermath

After the battle, the bodies of several of the conflict's U.S. casualties (Black Hawk Super 64's crewmembers and their defenders, Delta Force soldiers MSG Gordon and SFC Shughart) were dragged through Mogadishu's streets by crowds of local civilians and SNA forces.[55] Through negotiation and threats to the Habr Gidr clan leaders by ambassador Robert B. Oakley, all the bodies were eventually recovered. The bodies were returned in poor condition, one with a severed head. Michael Durant was released after 11 days of captivity. On the beach near the base, a memorial was held for those who were killed in combat.[56]

Known casualties

Pakistan

A Pakistani soldier was killed and two were wounded during the rescue attempt and assault. Tanks of 6 Lancer Regiment and 19 Lancer Regiment were used for the rescue. The soldier killed was from 19 Lancer Regiment manning a 12.7 mm turret gun.[57]

Malaysia

Lance Corporal Mat Aznan Awang was an 18 year old soldier of the 19th Battalion, Royal Malay Regiment of the Malaysian Army (posthumously promoted to Corporal). Driving a Malaysian Condor armoured personnel carrier, he was killed when his vehicle was hit by an RPG on 3 October.[35] Corporal Mat Aznan Awang was awarded the Seri Pahlawan Gagah Perkasa medal (Gallant Warrior/Warrior of Extreme Valor).[40][58]

Somalia

Ambassador Robert B. Oakley, the U.S. special representative to Somalia, is quoted as saying: "My own personal estimate is that there must have been 1,500 to 2,000 Somalis killed and wounded that day, because that battle was a true battle. And the Americans and those who came to their rescue, were being shot at from all sides ... a deliberate war battle, if you will, on the part of the Somalis. And women and children were being used as shields and some cases women and children were actually firing weapons, and were coming from all sides. Sort of a rabbit warren of huts, houses, alleys, and twisting and turning streets, so those who were trying to defend themselves were shooting back in all directions. Helicopter gun ships were being used as well as all sorts of automatic weapons on the ground by the U.S. and the United Nations. The Somalis, by and large, were using automatic rifles and grenade launchers and it was a very nasty fight, as intense as almost any battle you would find."[59]

Reliable estimates place the number of Somali insurgents killed at between 800 and as many as 1,000 with perhaps another 4,000 wounded. Somali militants claimed a much lower casualty rate.[60] Aidid himself claimed that only 315 – civilians and militia – were killed and 812 wounded.[6] Captain Haad, in an interview on American public television, said 133 of the SNA militia were killed.[8]

United States

| Name | Age | Action | Medal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operators of the 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta | |||

| MSG Gary Ivan Gordon | 33 | Killed defending Super Six-Four's crew | Medal of Honor, Purple Heart[35] |

| SFC Randy Shughart | 35 | Killed defending Super Six-Four's crew | Medal of Honor, Purple Heart[35] |

| SSG Daniel D. Busch | 25 | Crashed on Super Six-One, mortally wounded defending the downed crew | Silver Star, Purple Heart[58] |

| SFC Earl Robert Fillmore, Jr. | 28 | Killed moving to the first crash site | Silver Star, Purple Heart[61] |

| MSG Timothy "Griz" Lynn Martin | 38 | Mortally wounded by an RPG on the Lost Convoy, died while en route to a field hospital in Germany | Silver Star, Purple Heart.[62][63] |

| Soldiers of the 3rd Ranger Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment | |||

| CPL James "Jamie" E. Smith | 21 | Killed around crash site one | Bronze Star Medal with Valor Device and Oak leaf cluster, Purple Heart[64] |

| SPC James M. Cavaco | 26 | Killed on the Lost Convoy | Bronze Star with Valor Device, Purple Heart[65] |

| SGT James Casey Joyce | 24 | Killed on the Lost Convoy | Bronze Star with Valor Device, Purple Heart[65] |

| CPL Richard "Alphabet" W. Kowalewski, Jr. | 20 | Killed on the Lost Convoy by an RPG | Bronze Star with Valor Device, Purple Heart[66] |

| SGT Dominick M. Pilla | 21 | Killed on Struecker's convoy | Bronze Star with Valor Device, Purple Heart[66] |

| SGT Lorenzo M. Ruiz | 27 | Mortally wounded on the Lost Convoy, died en route to a field hospital in Germany | Bronze Star with Valor Device, Purple Heart[66] |

| Pilots and Crew of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment | |||

| SSG William "Wild Bill" David Cleveland, Jr. | 34 | Crew chief on Super Six-Four, killed | Silver Star, Bronze Star, Air Medal with Valor Device, Purple Heart[67] |

| SSG Thomas "Tommie" J. Field | 25 | Crew chief on Super Six-Four, killed | Silver Star, Bronze Star, Air Medal with Valor Device, Purple Heart |

| CW4 Raymond "Ironman" Alex Frank | 45 | Super Six-Four's copilot, killed | Silver Star, Air Medal with Valor Device, Purple Heart[68] |

| CW3 Clifton "Elvis" P. Wolcott | 36 | Super Six-One's pilot, died in crash | Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star, Air Medal with Valor Device, Purple Heart[67] |

| CW3 Donovan "Bull" Lee Briley | 33 | Super Six-One's copilot, died in crash | Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star, Air Medal with Valor Device, Purple Heart[69] |

| Soldiers of the 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade, 10th Mountain Division | |||

| SGT Cornell Lemont Houston, Sr. 41st Engr BN | 31 | Killed on the rescue convoy | Bronze Star with Valor Device, de Fleury Medal, Purple Heart[70] |

| PFC James Henry Martin, Jr. | 23 | Killed on the rescue convoy | Purple Heart[71] |

Military fallout

In a national security policy review session held in the White House on 6 October 1993, U.S. President Bill Clinton directed the Acting Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral David E. Jeremiah, to stop all actions by U.S. forces against Aidid except those required in self-defense. He reappointed Ambassador Robert B. Oakley as special envoy to Somalia in an attempt to broker a peace settlement and then announced that all U.S. forces would withdraw from Somalia no later than 31 March 1994. On 15 December 1993, U.S. Secretary of Defense Les Aspin stepped down, taking much of the blame for his decision to refuse requests for tanks and armored vehicles in support of the mission.[72][73] A few hundred U.S. Marines remained offshore to assist with any noncombatant evacuation mission that might occur regarding the 1,000-plus U.S. civilians and military advisers remaining as part of the U.S. liaison mission. The Ready Battalion of the 24th Infantry Division, 1–64 Armor, was sent from Fort Stewart, Georgia, to Mogadishu to provide armored support for U.S. forces.

On 4 February 1994, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 897, which set a process for completing the UNOSOM II mission by March 1995, with the withdrawal of U.N. troops from Somalia at that time. In August 1994, the UN requested that the US lead a coalition to aid in the final withdrawal of the UNOSOM II forces from Somalia. On 16 December 1994, Operation United Shield was approved by President Clinton and launched on 14 January 1995. On 7 February 1995, the Operation United Shield multi-national fleet arrived and began the withdrawal of UNOSOM II's forces. On 6 March 1995, all of the remaining U.N. troops were withdrawn, ending UNOSOM II.

Policy changes and political implications

.jpg)

The mission in Somalia was seen by many as a failure.[74] The Clinton administration in particular endured considerable criticism for the operation's outcome. The main elements of the criticism surround the administration's decision to leave the region before completing the operation's humanitarian and security objectives, as well as the perceived failure to recognize the threat Al-Qaida elements posed in the region as well as the threat against U.S. security interests at home.[75] Critics claim that Osama bin Laden and other members of Al-Qaida provided support and training to Mohammed Farrah Aidid's forces. Osama bin Laden even denigrated the administration's decision to prematurely depart the region stating that it displayed "the weakness, feebleness and cowardliness of the US soldier".[76]

The loss of U.S. military personnel during the Black Hawk Down operation evoked public outcry. Television images of American soldiers being dragged through the streets by Somalis were too graphic for the American public to endure. The Clinton administration responded by scaling down U.S. humanitarian efforts in the region.[76]

On 26 September 2006, in an interview on Fox News with Chris Wallace, former President Bill Clinton gave his version of events surrounding the mission in Somalia. Clinton defended his exit strategy for U.S. forces and denied that the departure was premature. He said conservative Republicans had pushed him to leave the region before the operation's objectives could be achieved: "...[Conservative Republicans] were all trying to get me to withdraw from Somalia in 1993 the next day after we were involved in 'Black Hawk down,' and I refused to do it and stayed six months and had an orderly transfer to the United Nations."[77]

Clinton's remarks would suggest the U.S. was not deterred from pursuing their humanitarian goals because of the loss of U.S. forces during Black Hawk Down. In the same interview, he stated that, at the time, nobody thought Osama bin Laden and Al-Qaida had anything to do with Black Hawk Down's events. He said the mission was strictly humanitarian.[77]

Fear of a repeat of the events in Somalia shaped U.S. policy in subsequent years, with many commentators identifying the Battle of Mogadishu's graphic consequences as the key reason behind the U.S.'s failure to intervene in later conflicts such as the Rwandan Genocide of 1994. According to the U.S.'s former deputy special envoy to Somalia, Walter Clarke: "The ghosts of Somalia continue to haunt US policy. Our lack of response in Rwanda was a fear of getting involved in something like a Somalia all over again."[78] Likewise, during the Iraq War when four American contractors were killed in the city of Fallujah, then dragged through the streets and desecrated by an angry mob, direct comparisons by the American media to the Battle of Mogadishu led to the First Battle of Fallujah.[79]

Links with Al-Qaeda

There have been allegations that Osama bin Laden's Al-Qaeda organization was involved in training and funding of Aidid's men. In his 2001 book, Holy War, Inc., CNN reporter Peter Bergen interviewed bin Laden who affirmed these allegations. According to Bergen, bin Laden asserted that fighters affiliated with his group were involved in killing U.S. troops in Somalia in 1993, a claim he had made earlier to the Arabic newspaper Al-Quds Al-Arabi. The Al-Qaeda fighters in Somalia are rumored to have included the organization's military chief, Mohammed Atef, later killed by U.S. forces in Afghanistan. Another al-Qaeda operative who was present at the battle was Zachariah al-Tunisi, who allegedly fired an RPG that downed one of the Black Hawk helicopters; he was later killed by an airstrike in Afghanistan in November 2001.[80]

Aidid's men received some expert guidance in shooting down helicopters from fundamentalist Islamic soldiers, most likely Al-Qaeda, who had experience fighting Russian helicopters during the Soviet-Afghan War.[33] A document recovered from Al-Qaeda operative Wadih el-Hage's computer "made a tentative link between al-Qaeda and the killing of American servicemen in Somalia," and were used to indict bin Laden in June 1998.[81] Al-Qaeda defector Jamal al-Fadl also claimed that the group had trained the men responsible for shooting down the U.S. helicopters.[82]

Four and a half years after the Battle of Mogadishu, in an interview in May 1998, bin Laden disparaged the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Somalia.[83] While he had previously claimed responsibility for the ambush,[84] bin Laden denied having orchestrated the attack on the U.S. soldiers in Mogadishu but expressed delight at their deaths in battle against Somali fighters.[83]

In a 2011 interview, Moktar Ali Zubeyr, the leader of the Somali militant Islamist group Al-Shabaab, said that three al Qaeda leaders were present during the battle of Mogadishu. Zubeyr named Yusef al-Ayeri, Saif al-Adel, and Sheikh Abu al Hasan al Sa'idi as providing help through training or participating in the battle themselves.[2]

Published accounts

In 1999, writer Mark Bowden published the book Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War, which chronicles the events that surrounded the battle. The book was based on his series of columns for The Philadelphia Inquirer about the battle and the men who fought.

Black Hawk pilot Michael Durant told his story of being shot down and captured by a mob of Somalis in his 2003 book In the Company of Heroes.

In 2005, Staff Sergeant Matthew Eversmann, a U.S. Army Ranger and Chalk Four's leader during the battle, compiled several different accounts into a book called The Battle of Mogadishu.

In 2008 Lieutenant General William G. "Jerry" Boykin, former Delta Force Commander and Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence included a section on his account of the battle in his book "Never Surrender: A Soldier's Journey to the Crossroads of Faith and Freedom".

In 2011, Staff Sergeant Keni Thomas, a U.S. Army Ranger recounted the combat experience in "Get It On!: What It Means to Lead the Way."

Howard E. Wasdin's SEAL Team Six (2011) includes a section about his time in Mogadishu including the Pasha CIA safe house and multiple operations including the Battle of Mogadishu where he was severely wounded.[85]

In 2013, Lieutenant Colonel Michael Whetstone, Company Commander of Charlie Company 2–14 Infantry published his memoirs of the heroic rescue operation of Task Force Ranger in his book Madness in Mogadishu.[86]

Film

In 2001, Bowden's book was adapted into the film Black Hawk Down, produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and directed by Ridley Scott. Like the book, the film describes events surrounding the operation, but there are differences between the book and the film, such as Rangers marking targets at night by throwing strobe lights at them, when in reality the Rangers marked their own positions and close air support targeted everything else.[87]

Documentaries

The True Story of Black Hawk Down (2003) is a TV documentary which premièred on The History Channel. It was directed by David Keane.

The American Heroes Channel television series, Black Ops, aired an episode titled "The Real Black Hawk Down," in June 2014.[88]

The National Geographic Channel television series, No Man Left Behind, aired an episode titled "The Real Black Hawk Down," in June 28th 2016.[89]

Rangers return in 2013

In March 2013, two survivors from Task Force Ranger returned to Mogadishu with a film crew to shoot a short film, Return to Mogadishu: Remembering Black Hawk Down, which debuted in October 2013 on the 20th anniversary of the battle. Author Jeff Struecker and country singer/songwriter Keni Thomas relived the battle as they drove through the Bakaara Market in armored vehicles and visited the Wolcott crash site.[90]

Super 61 returns to US

In August 2013, remains of Super 61, consisting of the mostly intact main rotor and parts of the nose section, were extracted from the crash site and returned to the United States due to the efforts of David Snelson and Alisha Ryu, and are on display at the Airborne & Special Operations Museum at Fort Bragg, Fayetteville, North Carolina.[91] The exhibit features immersive dioramas and artifacts from the battle including the wreckage of Super 6-1, the first Black Hawk helicopter shot down during the battle, and Super 6-4.[92]

See also

- Battle of Mogadishu (2006)

- Battle of Mogadishu (2008)

- Battle of Mogadishu (2009)

- Battle of Mogadishu (2010–11)

- Battle of Mogadishu (March–April 2007)

- Battle of Mogadishu (November 2007)

- Battle of South Mogadishu (2009)

- Fall of Mogadishu (2006)

- Somali Civil War

References

- ↑ Robert M. Cassidy (Ph.D.) (2004). Peacekeeping in the Abyss: British and American Peacekeeping Doctrine and Practice After the Cold War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-275-97696-5.

Understanding the "Victory Disease," From the Little Bighorn to Mogadishu and Beyond. DIANE Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4289-1052-2.

Mark Bowden (1 April 2010). Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War. Grove/Atlantic, Incorporated. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-55584-604-6. - 1 2 "Shabaab leader recounts al Qaeda's role in Somalia in the 1990s". Long War Journal. 2011-12-30. Retrieved 2014-07-01.

- ↑ Mark Bowden (16 November 1997). "Blackhawk Down". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- 1 2 Atkinson, Rick (1994-01-31). "Night of a Thousand Casualties". The Washington Post . Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ↑ "Anatomy of a Disaster". Time. 18 October 1993. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Human Rights Developments, retrieved on 10 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 Bowden, Mark (16 November 1997). "Black Hawk Down: A defining battle". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- 1 2 "Interviews – Captain Haad | Ambush in Mogadishu | FRONTLINE". PBS. 3 October 1993. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Bowden, Mark (16 November 1997). "Black Hawk Down". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on 23 September 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- ↑ Ambush In Mogadishu – PBS Frontline. Pbs.org. 29 September 1998.

- ↑ Bowden, Mark (16 November 1997) "Black Hawk Down ". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved on 1 May 2014.

- ↑ Adejumobi, Saheed A. (2007). The history of Ethiopia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-313-32273-0.

- ↑ "Somalia: Anatomy of a Disaster". Time. 18 October 1993.

- ↑ Battlefield Somalia: The Battle of Mogadishu. Militaryfactory.com. Retrieved on 1 May 2014.

- ↑ "Ambush In Mogadishu | PBS – FRONTLINE". PBS. 3 October 1993. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ "Somalia Battle Killed 12 Americans, Wounded 78". The Washington Post. 7 August 2006.

- ↑ Serrill, Michael (12 August 1996), "Death of a Warlord", Time, retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ Peterson, Scott (2001). Me Against My Brother: At War in Somalia, Sudan and Rwanda. Psychology Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-415-93063-5.

- 1 2 Battersby, Paul; Joseph M. Siracusa (2009). Globalization and human security. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-7425-5653-9.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Nina J. (2002). Somalia: Issues, History, and Bibliography. Nova Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 1590332652.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Clancy, Tom; Tony Zinni; Tony Koltz (2005). Battle Ready: Study in Command Commander Series. Penguin. pp. 234–236. ISBN 978-0-425-19892-6.

- ↑ UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN SOMALIA II. UN.org (31 August 1996). Retrieved on 1 May 2014.

- ↑ Security Council, Resolution 837, United Nations Doc. Nr. S/RES/837 (1993)

- ↑ Brune, Lester H. (1999) The United States and Post-Cold War Interventions: Bush and Clinton in Somalia, Haiti and Bosnia, 1992–1998, Regina Books, ISBN 0941690903, p. 28

- ↑ Bowden, p. 95

- ↑ Bowden, p. 95.

- ↑ Chris Albin-Lackey, Human Rights Watch (Organization), "So much to fear": war crimes and the devastation of Somalia, Human Rights Watch, 2008, p. 44

- ↑ Bowden, Mark (1 June 2000). "African Atrocities and the Rest of the World". Policy Review No. 101. Hoover Institute. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ↑ Yahoo.com, Kevin Sites Black Hawk Ground 26 September 2005, Yahoo News.

- ↑ Bowden, p. 114

- ↑ Brune, Lester H. (1999) The United States and Post-Cold War Interventions: Bush and Clinton in Somalia, Haiti and Bosnia, 1992–1998, Regina Books, ISBN 0941690903, p. 31

- ↑ Bailey, Tracy A (6 October 2008). "Rangers Honor Fallen Brothers of Operation Gothic Serpent". ShadowSpear Special Operations. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- 1 2 Bowden, p. 133

- ↑ Chun, Clayton K.S. (2012). Gothic Serpent: Black Hawk Down, Mogadishu 1993. Osprey Raid Series #31. Osprey Publishing. p. 32.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Willbanks, James H. (2011). America's Heroes: Medal of Honor Recipients from the Civil War to Afghanistan. ABC-CLIO. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-59884-393-4.

- ↑ Carney, John T.; Benjamin F. Schemmer (2003). No Room for Error: The Story Behind the USAF Special Tactics Unit. Random House. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-345-45335-8.

- ↑ Baumann, Robert (2003). "My Clan Against the World": U.S. and Coalition Forces in Somalia 1992–1994. DIANE Publishing. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-4379-2308-7.

- ↑ 41st Engineer Battalion. tioh.hqda.pentagon.mil

- 1 2 The Sabre & Lance: Journal of the Pakistan Armoured Corps. (1997). Nowshera: The School of Armour & Mechanised Warfare.

- 1 2 3 4 IBP USA (2007). Malaysia Army Weapon Systems Handbook. Int'l Business Publication. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-1-4330-6180-6.

- 1 2 Musharraf, Pervez (2006). In the line of fire: a memoir. Simon and Schuster. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-7432-8344-1.

- ↑ Bowden, p. 83

- ↑ Clarke, Walter S. (2 February 1993). "Background Information For Operation Restore Hope" (PDF). Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army College.

- ↑ "To Fight With Intrepidity". Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ↑ Casper, Lawrence E. (2001). Falcon Brigade: Combat and Command in Somalia and Haiti. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-55587-945-7.

- 1 2 Bowden, p. 34

- ↑ "Blackhawk Down". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Eversmann, p. 129

- 1 2 Eversmann, pp. 34–36

- ↑ The Independent, 12 January 2002, "Black Hawk Down: Shoot first, don't ask questions afterwards", retrieved on 14 December 2006.

- ↑ Eversmann, pp. 99–100

- ↑ Ambush in Mogadishu 29 September 1998 (Original broadcast date), retrieved on 10 November 2009.

- ↑ Casper, Lawrence E. (2001). Falcon Brigade: Combat and Command in Somalia and Haiti. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-55587-945-7.

- ↑ Moore, Robin.; Michael Lennon (2007). The Wars of the Green Berets: Amazing Stories from Vietnam to the Present. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-60239-054-6.

- ↑ Watson, Paul. "Pulitzer Prize-Winning Photo" (acceptance of terms of use required). Toronto Star.

- ↑ Oakley, Robert B.; John L. Hirsch (1995). Somalia and Operation Restore Hope: Reflections on Peacemaking and Peacekeeping. United States Institute of Peace Press. pp. 127–131. ISBN 978-1-878379-41-2.

- ↑ Mickolus, Edward F.; Susan L. Simmons (1997). Terrorism, 1992–1995: A Chronology of Events and a Selectively Annotated Bibliography. ABC-CLIO. pp. 234–236. ISBN 978-0-313-30468-2.

- 1 2 Bowden, p. 86

- ↑ "Interviews – Ambassador Robert Oakley | Ambush in Mogadishu | FRONTLINE". PBS. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Dougherty, Martin, J. (2012) 100 Battles: Decisive Battles that Shaped the World, Parragon, ISBN 1445467631, p. 247

- ↑ Bowden, p. 179

- ↑ "Timothy L. Martin". Arlington National Cemetery Website. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ "Silver Star Awards in Somalia during Operation Restore Hope". Home of Heroes. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ Bowden, p. 136

- 1 2 Bowden, p. 265

- 1 2 3 Bowden, p. 301

- 1 2 Bowden, p. 96

- ↑ Bowden, p. 193

- ↑ Bowden, pp. 141–143

- ↑ Bowden, p. 274

- ↑ Bowden, p. 27

- ↑ Warshaw, Shirley Anne (2004). The Clinton Years: Presidential Profiles Facts on File Library of American History (2 ed.). Infobase Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8160-5333-9.

- ↑ Johnson, Loch K. (2011). The Threat on the Horizon: An Inside Account of America's Search for Security after the Cold War. Oxford University Press. pp. 7, 19, 26. ISBN 978-0-19-973717-8.

- ↑ Johnson, Dominic D. P. and Tierney, Dominic (2006) Failing to Win: Perceptions of Victory and Defeat in International Politics. Harvard University Press, p. 210. ISBN 0-674-02324-2

- ↑ Miniter, Richard (2004) Losing Bin Laden: How Bill Clinton's Failures Unleashed Global Terror. Regnery Publishing, p. 44, ISBN 0-89526-048-4

- 1 2 Thornton, Rod (2007) Asymmetric Warfare: Threat and Response in the Twenty-First Century, p. 10, ISBN 0-7456-3365-X

- 1 2 "Transcript: William Jefferson Clinton". Foxnews.com. 26 September 2006. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ "Ambush in Mogadishu: Transcript". PBS. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- ↑ "U.S. expects more attacks in Iraq". CNN. 6 May 2004. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Soufan, Ali. (2011). The Black Banners: The Inside Story of 9/11 and the War Against al-Qaeda. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-393-07942-5.

- ↑ Wright 2006, p. 266.

- ↑ Wright 2006, p. 5.

- 1 2 "Who Is Bin Laden? – Interview With Osama Bin Laden (in May 1998) | Hunting Bin Laden | FRONTLINE". PBS. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Wright 2006, p. 246.

- ↑ Wasdin, Howard E. (2011). SEAL Team Six: Memoirs of an American Sniper. St. Martin's Press. pp. 177–279. ISBN 978-0-312-69945-1.

- ↑ Whetstone, Michael (2013). Madness in Mogadishu. Michael L. Whetstone. p. 250. ASIN B00GRY49AU.

- ↑ Eberwein, Robert T. (2004). The war film. Rutgers University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-8135-3497-8.

- ↑ https://www.ahctv.com/tv-shows/black-ops/tv-schedule.htm Archived 22 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/no-man-left-behind/episodes/the-real-black-hawk-down/

- ↑ Gustafson, Dave (4 October 2013). "20 years after Black Hawk Down, a 'Return to Mogadishu'". Al Jazeera America.

- ↑ Logan, Lara (6 October 2013) CBS 60-Minutes: Black Hawk Down Site Revisited 20 Years Later. Cbsnews.com. Retrieved on 1 May 2014.

- ↑ "Task Force Ranger and the Battle of Mogadishu Exhibit". asomf.org. Airborne & Special Operations Museum Foundation. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

Bibliography

- Bowden, Mark (1999). Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War. Atlantic Monthly Press.

- Eversmann, Matthew (SSG) (2005). The Battle of Mogadishu: Firsthand Accounts from the Men of Task Force Ranger. Presidio Press. ISBN 0345466683.

- Wright, Lawrence (2006). The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Knopf. ISBN 037541486X.

Further reading

- Allard, Colonel Kenneth, Somalia Operations: Lessons Learned, National Defense University Press (1995).

- Boykin, William (Maj. Gen.), Never Surrender, Faith Words, New York, NY, (2008).

- Chun, Clayton K.S., Gothic Serpent: Black Hawk Down, Mogadishu 1993. Osprey Raid Series #31. Osprey Publishing (2012). ISBN 9781849085847

- Clarke, Walter, and Herbst, Jeffrey, editors, Learning from Somalia: The Lessons of Armed Humanitarian Intervention, Westview Press (1997).

- Durant, Michael (CWO4), In the Company of Heroes, (2003 hb, 2006 pb).

- Gardner, Judith and el Bushra, Judy, editors, Somalia – The Untold Story: The War Through the Eyes of Somali Women, Pluto Press (2004).

- O'Connell, James Patrick (SGT.), Survivor Gun Battle Mogadishu, US Army Special Forces. (New York City) (1993).

- Prestowitz, Clyde, Rogue Nation: American Unilateralism and the Failure of Good Intentions, Basic Books (2003).

- Sangvic, Roger, Battle of Mogadishu: Anatomy of a Failure, School of Advanced Military Studies, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (1998).

- Stevenson, Jonathan, Losing Mogadishu: Testing U.S. Policy in Somalia, Naval Institute Press (1995).

- Stewart, Richard W., The United States Army in Somalia, 1992–1994, United States Army Center of Military History (2003).

- Somalia: Good Intentions, Deadly Results, VHS, produced by KR Video and The Philadelphia Inquirer (1998).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Mogadishu (1993). |

- Black Hawk Down, Philadelphia Inquirer

- PBS – Ambush in Mogadishu, PBS

Coordinates: 2°03′09″N 45°19′29″E / 2.05250°N 45.32472°E