Baltic languages

| Baltic | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity: | Balts |

| Geographic distribution: | Northern Europe |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Subdivisions: |

|

| ISO 639-5: | bat |

| Linguasphere: | 54= (phylozone) |

| Glottolog: |

None east2280 (East Baltic)[1] prus1238 (Prussian)[2] |

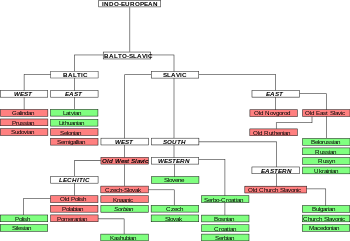

The Baltic languages belong to the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. Baltic languages are spoken by the Balts, mainly in areas extending east and southeast of the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe.

Scholars usually regard them as a single language family divided into two groups: Western Baltic (containing only extinct languages), and Eastern Baltic (containing two living languages, Lithuanian and Latvian). The range of the Eastern Balts once reached to the Ural mountains.[3][4][5]

Old Prussian, a Western Baltic language which became extinct in the 18th century, ranks as the most archaic of the Baltic languages.[6]

Although related, the Lithuanian, the Latvian, and particularly the Old Prussian vocabularies differ substantially from one another and are not mutually intelligible.

Branches

The Baltic languages are generally thought to form a single family with two branches, Eastern and Western. However, these two branches are sometimes classified as independent branches of Balto-Slavic.[2]

Western Baltic languages †

- (Western) Galindian †

- Old Prussian †

- Sudovian (Yotvingian) †

- ? Skalvian †

Eastern Baltic languages

- Latvian (~2–2.5 million speakers, whereof ~1.39 million native speakers, 0.5–1 million ethnic Russian speakers, 0.15 million others)

- Latgalian (165 thousand speakers; usually considered a dialect of Latvian)

- New Curonian (nearly extinct; often considered a separate language, but mutually intelligible to Latvian)

- Lithuanian (~3.9 million speakers)

- Samogitian (~0.5 million speakers; usually considered a dialect of Lithuanian)

- Selonian †

- Semigallian †

- Old Curonian (sometimes considered Western Baltic) †

- (Eastern) Galindian (the language of the Eastern Galindians, also known by its name in Russian: Голядь Golyad') †

(†—Extinct language)

Geographic distribution

Speakers of modern Baltic languages are generally concentrated within the borders of Lithuania and Latvia, and in emigrant communities in the United States, Canada, Australia and the countries within the former borders of the Soviet Union.

Historically the languages were spoken over a larger area: west to the mouth of the Vistula river in present-day Poland, at least as far east as the Dniepr river in present-day Belarus, perhaps even to Moscow, and perhaps as far south as Kiev. Key evidence of Baltic language presence in these regions is found in hydronyms (names of bodies of water) that are characteristically Baltic. Use of hydronyms is generally accepted to determine the extent of a culture's influence, but not the date of such influence.

Eventual expansion of the usage of Slavic languages in the south and east, and Germanic languages in the west reduced the geographic distribution of Baltic languages to a fraction of the area that they formerly covered.

Though included among the Baltic states due to its location, the language of Estonia, Estonian, is a Uralic language and is not related to the Baltic languages, which are Indo-European.

Prehistory and history

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe East-Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East-Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

Religion and mythology

Indian Iranian Other Europe |

It is believed that the Baltic languages are among the most archaic of the currently remaining Indo-European languages, despite their late attestation.

Although the various Baltic tribes were mentioned by ancient historians as early as 98 B.C., the first attestation of a Baltic language was in about 1350, with the creation of the Elbing Prussian Vocabulary, a German to Prussian translation dictionary. Lithuanian was first attested in a hymnal translation in 1545; the first printed book in Lithuanian, a Catechism by Martynas Mažvydas was published in 1547 in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia). Latvian appeared in a hymnal in 1530 and in a printed Catechism in 1585.

One reason for the late attestation is that the Baltic peoples resisted Christianization longer than any other Europeans, which delayed the introduction of writing and isolated their languages from outside influence.

With the establishment of a German state in Prussia, and the eradication or flight of much of the Baltic Prussian population in the 13th century, the remaining Prussians began to be assimilated, and by the end of the 17th century, the Prussian language had become extinct.

During the years of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795), official documents were written in Polish, Ruthenian and Latin.

After the Partitions of Commonwealth, most of the Baltic lands were under the rule of the Russian Empire, where the native languages or alphabets were sometimes prohibited from being written down or used publicly in a Russification effort (see Lithuanian press ban for the ban in force from 1865 to 1904).

Relationship with other Indo-European languages

The Baltic languages are of particular interest to linguists because they retain many archaic features, which are believed to have been present in the early stages of the Proto-Indo-European language.[7] However, linguists have had a hard time establishing the precise relationship of the Baltic languages to other languages in the Indo-European family.[8] Several of the extinct Baltic languages have a limited or nonexistent written record, their existence being known only from the records of ancient historians and personal or place names. All of the languages in the Baltic group (including the living ones) were first written down relatively late in their probable existence as distinct languages. These two factors combined with others have obscured the history of the Baltic languages, leading to a number of theories regarding their position in the Indo-European family.

The Baltic languages show a close relationship with the Slavic languages, and are grouped with them in a Balto-Slavic family by most scholars. This family is considered to have developed from a common ancestor, Proto-Balto-Slavic. Later on, several lexical, phonological and morphological dialectisms developed, separating the various Balto-Slavic languages from each other.[9][10] Although it is generally agreed upon that the Slavic languages developed from a single more-or-less unified dialect (Proto-Slavic) that split off from common Balto-Slavic, there is more disagreement about the relationship between the Baltic languages.

The traditional view is that the Balto-Slavic languages split into two branches, Baltic and Slavic, with each branch developing as a single common language (Proto-Baltic and Proto-Slavic) for some time afterwards. Proto-Baltic is then thought to have split into East Baltic and West Baltic branches. However, more recent scholarship has suggested that there was no unified Proto-Baltic stage, but that Proto-Balto-Slavic split directly into three groups: Slavic, East Baltic and West Baltic.[11][12] Under this view, the Baltic family is paraphyletic, and consists of all Balto-Slavic languages that are not Slavic. This would imply that Proto-Baltic, the last common ancestor of all Baltic languages, would be identical to Proto-Balto-Slavic itself, rather than distinct from it.

Finally, there is a minority of scholars who argue that Baltic descended directly from Proto-Indo-European, without an intermediate common Balto-Slavic stage. They argue that the many similarities and shared innovations between Baltic and Slavic are due to several millennia of contact between the groups, rather than shared heritage.[13]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "East Baltic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Prussian". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Marija Gimbutas 1963. The Balts. London : Thames and Hudson, Ancient peoples and places 33.

- ↑ J. P. Mallory, "Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture", Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997

- ↑ David W. Anthony, "The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World", Princeton University Press, 2007

- ↑ Ringe, D., Warnow, T., Taylor, A., 2002. Indo-European and computational cladistics. Trans. Philos. Soc. 100, 59–129.

- ↑ Marija Gimbutas (1963). The balts, by marija gimbutas. Thames and hudson. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ Ancient Indo-European Dialects. University of California Press. pp. 139–151. GGKEY:JUG4225Y4H2. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ J. P. Mallory (1 April 1991). In search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27616-7. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ J. P. Mallory (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ Kortlandt, Frederik (2009), Baltica & Balto-Slavica, p. 5,

Though Prussian is undoubtedly closer to the East Baltic languages than to Slavic, the characteristic features of the Baltic languages seem to be either retentions or results of parallel development and cultural interaction. Thus I assume that Balto-Slavic split into three identifiable branches, each of which followed its own course of development.

- ↑ Derksen, Rick (2008), Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon, p. 20,

I am not convinced that it is justified to reconstruct a Proto-Baltic stage. The term Proto-Baltic is used for convenience’s sake.

- ↑ Hans Henrich Hock; Brian D. Joseph (1996). Language history, language change, and language relationship: an introduction to historical and comparative linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-11-014784-1. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

References

- Ernst Fraenkel (1950) Die baltischen Sprachen, Carl Winter, Heidelberg, 1950

- Joseph Pashka (1950) Proto Baltic and Baltic languages

- Lituanus Linguistics Index (1955–2004) provides a number of articles on modern and archaic Baltic languages

- Mallory, J. P. (1991) In Search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. New York: Thames and Hudson ISBN 0-500-27616-1

- Algirdas Girininkas (1994) "The monuments of the Stone Age in the historical Baltic region", in: Baltų archeologija, N.1, 1994 (English summary, p. 22). ISSN 1392-0189

- Algirdas Girininkas (1994) "Origin of the Baltic culture. Summary", in: Baltų kultūros ištakos, Vilnius: "Savastis" ISBN 9986-420-00-8"; p. 259

- Edmund Remys (2007) "General distinguishing features of various Indo-European languages and their relationship to Lithuanian", in: Indogermanische Forschungen; Vol. 112. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter

External links

- Baltic Online from the University of Texas at Austin