Dakota Access Pipeline

| Dakota Access Pipeline | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| General direction | Southeastward |

| From | Stanley, North Dakota |

| Passes through |

States of North Dakota (Bismarck) South Dakota (Redfield, Sioux Falls) Iowa (Sioux Center, Storm Lake, Ames, Oskaloosa, Ottumwa, Fort Madison Illinois (Jacksonville)[5] |

| To | Patoka, Illinois (oil tank farm) |

| General information | |

| Type | Crude oil |

| Partners |

Energy Transfer Partners Phillips 66 Enbridge (agreed) Marathon Petroleum (agreed) |

| Operator |

Dakota Access Pipeline, LLC (an ETP subsidiary, development phase) Sunoco Logistics Partners, L.P. (operational phase) |

| Construction started | 2016 |

| Expected | 2017 |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 1,134 mi (1,825 km) |

| Maximum discharge | 0.45 million barrels per day (~2.2×107 t/a) |

| Diameter | 30 in (762 mm) |

The Dakota Access Pipeline or Bakken pipeline is a 1,172-mile-long (1,886 km) underground oil pipeline project in the United States. The pipeline is currently under construction by Dakota Access, LLC, a subsidiary of the Dallas, Texas corporation Energy Transfer Partners, L.P. The route begins in the Bakken oil fields in northwest North Dakota and travels in a more or less straight line south-east, through South Dakota and Iowa, and ends at the oil tank farm near Patoka, Illinois. The project was planned for delivery by January 1, 2017.[6] As of November 26, 2016, the project was reported to be 87% completed.[7]

The $3.7 billion project was announced to the public in July 2014, and informational hearings for landowners took place between August 2014 and January 2015.[8] Dakota Access submitted its plan to the Iowa Utilities Board (IUB) on October 29, 2014, and applied for a permit in January 2015. The IUB was the last of the four state regulators to grant the permit in March 2016, including the use of eminent domain, after some public controversy. As of March 2016, Dakota Access had secured voluntary easements on 82 percent of Iowa land.

The pipeline has been controversial regarding its necessity, and potential impact on the environment. A number of Native Americans in Iowa and the Dakotas have opposed the pipeline, including the Meskwaki and several Sioux tribal nations. In August 2016, ReZpect Our Water, a group organized on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, brought a petition to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Washington, D.C. and the tribe sued for an injunction. A protest at the pipeline site in North Dakota near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation has drawn international attention. Thousands of people have been protesting the pipeline construction, with confrontations between some groups of protesters and law enforcement, along with disputes over the facts.

Description

The pipeline has a permanent easement of 50 feet (15 m) and a construction right-of-way of up to 150 feet (46 m) . The 30-inch (760 mm) diameter pipeline is at least 48 inches (1.2 m) underground from the top of the pipe or 2 feet (0.61 m) below any drain tiles.[9]

The pipeline will carry 470,000 barrels per day (75,000 m3/d) of crude oil "based on contractual commitments to date".[10]

The company estimated the pipeline would cost $3.7 billion – including $189 million to pay landowners – and create up to 40 permanent jobs,[11] besides 8,200-12,000 temporary jobs. As of December 2014 informational meetings for landowners had been held in all counties of Iowa to explain right of way issues. The company was working on applications for a "hazardous liquid pipeline permit" with the four respective state agencies regulating utilities.[12]

Purpose

.jpg)

Dakota Access, LLC's planning applications argued that the pipeline was needed to improve the overall safety to the public, would help the US to attain energy independence, and was a more reliable method of transport to refineries than rail or road. The company also estimated pipeline construction would provide 8,000-12,000 temporary jobs and 40 permanent jobs.[11] Proponents have argued that the pipeline will free up railroads which will allow farmers to ship more Midwest grain.[13]

Energy Transfer said it expected that the project would create between 12 and 15 permanent jobs and from 2,000 to 4,000 temporary jobs. The $1.35 billion capital investment was projected to generate $33 million in Iowa sales tax during construction and $30 million in property tax in 2017.[12] According to the Des Moines Register, Energy Transfer hired "Strategic Economics Group" in West Des Moines to prepare this analysis.[14] Dave Swenson, an Iowa State University economics professor, said that "a strong fraction of work will accumulate to out-of-state employers who will bring in their skilled labor and then subcontract what they can along the way" to local concerns.[15]

In January 2014, after recent rail derailments in Alabama, North Dakota and in Quebec, the US Department of Transportation's PHMSA issued a safety alert because the resulting fires suggested that the Bakken crude might be more flammable than other grades of oil.[16] As of July 2014 Bakken shale oil was transported through nine Iowa counties exclusively via three freight trains per week.[17] As of June 2014, 32 trains per week carrying Bakken oil traveled through Jo Daviess County in northwestern Illinois. At that time, 70% of Bakken oil was being transported by rail because of pipeline limitations.[18]

Ownership

Dakota Access, LLC, a fully owned subsidiary of Energy Transfer Partners LP (ETP), a master limited partnership based in Dallas, Texas, owns 75% of the pipeline, while Houston-based Phillips 66 owns a 25% stake. Phillips 66 also co-owns another part of the Bakken system, the Energy Transfer Crude Oil Pipeline which runs from Patoka to storage terminals in Nederland, Texas. It co-owns the storage terminals with Philadelphia-based Sunoco Logistics Partners.[19] Sunoco is a fully owned subsidiary of Energy Transfer Partners since 2012.[20]

In August 2016, the joint venture of Enbridge (75%) and Marathon Petroleum (25%) named MarEn Bakken Company agreed to purchase a 49% stake in Dakota Access, LLC for $2 billion. It gives Enbridge and Marathon indirect stakes in the pipeline of 27.6% and 9.2% respectively.[21][22] As of October 31, 2016, the deal was not completed.[23]

Financing

The pipeline project costs $3.7 billion, of which $2.5 billion was financed by loans while the rest of the capital would be raised by the sale of a 49% stake in Dakota Access, LLC (36.8% indirect stake in the pipeline) to Enbridge and Marathon Petroleum.[24] The loans were provided by a group of 17 banks. One activist group claimed the creditor group included Citibank, Wells Fargo, BNP Paribas, SunTrust, Royal Bank of Scotland, Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi, Mizuho Bank, TD Securities, ABN AMRO Capital, ING Bank, DNB ASA, ICBC, SMBC Nikko Securities and Société Générale.[25]

Due to protests against the pipeline, DNB ASA, which has provided over $342 million credit to the project, announced it will use its position as a lender "to encourage a more constructive process to find solutions to the conflict that has arisen."[26][27]

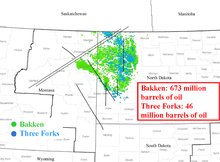

Route

The pipeline route runs from the northwestern North Dakota Bakken formation and Three Forks hydrofracturing sites starting in Stanley, North Dakota and travels in a southeastward direction to end at the oil tank farm near Patoka, Illinois.[19] It crosses 50 counties in four states.[28]

In North Dakota, the project consists of 143 miles (230 km) of oil gathering pipelines and 200 miles (322 km) of larger transmission pipeline. The route starts with a terminal in the Stanley area, and runs west with five more terminals in Ramberg Station, Epping, Trenton, Watford City and Johnsons Corner before becoming a transmission line going through Williston, the Watford City area, south of Bismarck, and crossing the Missouri River again north of Cannon Ball.[30]

In the early stages of route planning, Dakota Access proposed laying the pipeline northeast of Bismarck. According to the North Dakota Public Service Commission (NDPSC), the Bismarck route was 10 miles (16 km) longer and was rejected by the Army Corps of Engineers in an early environmental assessment before a request was made to the NDPSC for a permit. The route that was selected parallels the already existing Northern Border Pipeline, a natural gas pipeline built in the 1980s. The Dakota Access pipeline selected a "nearly identical route" and planned to cross the Missouri River near the same point.[31] The plans call for the pipeline to be directionally bored so that it will not come in contact with the Missouri River. It is planned to be "as deep as 90 feet (27.5 m)" below the riverbed.[32][33]

In South Dakota, the planned pipeline route travels through Campbell, McPherson, Edmunds, Faulk and Spink counties.[34]

In Iowa, the pipeline is projected to extend about 343 miles (552 km) diagonally through 18 Iowa counties: Lyon, Sioux, O'Brien, Cherokee, Buena Vista Sac, Calhoun, Webster, Boone, Story (which will have a pumping station), Polk, Jasper, Mahaska Keokuk, Wapello, Jefferson, Van Buren, and Lee.

History

On July 29, 2014, Energy Transfer partners had sought to meet with Iowa Utilities Board (IUB) members but had not yet filed a petition for regulatory review. Dakota Access, LLC wrote to landowners in the path of the pipeline requesting visits to survey in preparation for voluntary easement. The Iowa attorney general's chief deputy said he would advise letter recipients not to sign anything before consulting an attorney, but also said that if the utility board approved, Dakota Access, LLC would have the right to use eminent domain.[35]

In September 2014, the Dakota Pipeline, LLC held an initial informational meeting with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council. Prior to the presentation, Dave Archambault II indicated the tribe's opposition to any pipeline within treaty boundaries encompassing "North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming and South Dakota."[36]

Dakota Access held informational meetings for South Dakota landowners in October 2014.[12] As of February 2016, it had approved the pipeline.[37] As of March 2016, Dakota Access had secured voluntary easements on 93 percent of South Dakota land.[38]

In October 2014, Iowa Governor Terry Branstad "rejected pleas from a coalition of Iowa community and environmental activists who asked him to block plans"[39] and on October 29, 2014 Dakota Access, LLC submitted the project to the Iowa Utilities Board (IUB).[40]

Open House meetings for landowners took place in October 2014 in Illinois.[12] A webinar for Brown and Hancock County, Illinois took place in February 2015. Per filings before the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC), though Dakota Access, LLC still had no definite route and had secured voluntary easements from only nine of 908 Illinois landowners, the company requested the ICC grant it eminent domain.[41] As of 12 March 2014, no documents had been filed with the ICC.[42] and as of February 2016, it had approved the pipeline.[37] As of February 2016, all state regulators but Iowa had approved the pipeline.[37] As of March 2016, Dakota Access said it had secured voluntary easements on 92 percent of Illinois land.[38]

Starting on December 1, 2014, informational meetings in each of the affected counties began taking place,[43] with an official from the IUB, one from PMHSA, and one from Dakota Access, LLC presenting information.[44] Some 350 people showed up for the informational meeting in Fort Madison, Iowa, which "required some crowd control".[44][45] More than 300 people attended Sioux Center's informational meeting.[46] About 200 people attended in Oskaloosa, Iowa.[47] Some attendees expressed opposition to the pipeline, and many questions remained unanswered at the meeting in Storm Lake, Iowa.[48]

In January 2015, Dakota Access, LLC filed its pipeline application with the IUB.[49] In February 2015, it planned to file applications with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources for sovereign land and floodplain permits.[50]

In April 2015, Iowa Senate Study Bill 1276 and House Study Bill 249 advanced with both Senator Robert Hogg, D-Cedar Rapids, and State Representative Bobby Kaufmann, R-Wilton, in support; it required Energy Transfer's subsidiary Dakota Access "to obtain voluntary easements from 75 percent of property owners along the route before eminent domain could be authorized".[51]

In May 2015, a private landowner along the path of the pipeline accused a contractor of trying to negotiate land rights for the pipeline by offering the services of a teenage prostitute in return for the landowner's cooperation.[52]

On November 12, 2015, the Iowa Utilities Board heard public testimony during one day with more than 275 people signed up opposing the pipeline. There were 10 days scheduled for hearings by Dakota Access.[53]

In January 2016, Dakota Access filed 23 condemnation suits in North Dakota "against 140 individuals, banks and a coal mine".[54] As of February 2016, all state regulators but Iowa had approved the pipeline.[37] As of March 2016, Dakota Access had secured voluntary easements on 97 percent of North Dakota land, the highest proportion of the four affected states.[38]

In February 2016, the IUB had not made a decision after four days of hearings.[37] Nick Wagner, one of the three members of the Iowa Utilities Board and a former Republican state legislator, was asked to recuse himself for a conflict of interest, but refused to do so.[55]

On March 10, 2016, the IUB approved the Bakken Pipeline, on a vote of 3-0.[56] under the following conditions: "liability insurance of at least $25 million; guarantees that the parent companies of Dakota Access, LLC will pay for damages created by a pipeline leak or spill; a revised agricultural impact mitigation plan; a timeline for construction notices; modified condemnation easement forms; and a statement accepting the terms and condition's of the board's order."[57] One day later, the company stated it had secured voluntary easements on 82 percent of the 1,295 affected Iowa land parcels.[38]

In March 2016, Dakota Access, LLC filed motions with the IUB requesting expedited and confidential treatment to begin construction immediately, saying it met the conditions and that its liability insurance policies were trade secrets under Iowa law and "would serve no public purpose".[57]

In May 2016, the US Fish and Wildlife Service revoked the approval of an Iowa DNR sovereign lands construction permit in three counties, where the pipeline would cross the Big Sioux River and the Big Sioux Wildlife Management Area; these are historic and cultural sites of the Upper Sioux tribe.[58] Iowa farmers filed lawsuits to prevent the state from using eminent domain to take their land.[59]

In June 2016, the IUB voted 2 - 1 (Libby Jacobs and Nick Wagner in favor and Chairwoman Geri Huser against) to allow construction on non-sovereign lands to continue. The Sierra Club said this action was illegal before the US Corps of Engineers had authorized the project.[60]

In August 2016, 30 demonstrators were arrested in Boone, Iowa.[61]

According to state and federal authorities, there were several cases of arson that damaged pipeline construction equipment in Iowa during 2016. One deliberately set fire caused nearly $1 million in damage to construction equipment in August in Jasper County, Iowa. Two other fires involving pipeline construction equipment were set around the same time in the same county and another was set in Mahaska County.[62] In October, another arson fire caused $2 million worth of damage to pipeline construction equipment in Jasper County, Iowa.[63]

Federal agencies permissions

In March 2016, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had issued a sovereign lands construction permit. In late May 2016, the permit was temporarily revoked because of information about an Upper Sioux tribe historic and cultural site including graves in Lyon County.[58] In late June 2016, construction was allowed to resume in Lyon County after plans were changed to route the pipeline 85 feet (26 m) below the site using directional boring, instead of trenching and disturbing the soil on the surface.[64]

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers conducted a limited review of the route, involving an environmental assessment of river crossings and portions of the project related to specific permits, and issued a finding of no significant impact. It did not carry out an area-wide full environmental impact assessment of the entire effects of the overall project through the four states.[65] Citing potential effects on and lack of consultation with the Native American tribes, most notably the Standing Rock Sioux, in March and April 2016 the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Interior, and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation asked the Army Corps of Engineers to conduct a formal Environmental Impact Assessment and issue an Environmental Impact Statement. In July, however, the Army Corps of Engineers approved the water crossing permits for the Dakota Access Pipeline under a “fast track” option, and construction of the disputed section of pipeline continued.[66][67] Saying "the Corps effectively wrote off the tribe’s concerns and ignored the pipeline’s impacts to sacred sites and culturally important landscapes," the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe then filed suit against the Army Corps of Engineers, accusing the agency of violating the National Historic Preservation Act and other laws.[68] As of November 14, 2016, the Army Corps of Engineers has stated that, "construction on or under Corps land bordering Lake Oahe cannot occur because the Army has not made a final decision on whether to grant an easement".[67][69]

In September the U.S Department of Justice received more than 33,000 petitions to review all permits and order a full review of the project’s environmental effects.[70] On November 1, President Obama announced that his administration is monitoring the situation and has been in contact with the Army Corps to examine the possibility of rerouting the pipeline to avoid lands that Native Americans hold sacred.[71]

Concerns

Environmental concerns

Greenpeace and a group of 160+ scientists dedicated to conservation and preservation of threatened natural resources and endangered species have spoken out against the pipeline.[72][73][74] The Science & Environmental Health Network also rejects the pipeline.[75] Conservation groups worry about safety, and the impacts on air, water, wildlife and farming, because, they say, "pipelines break".[35] The Iowa Environmental Council has stated it is "concerned whether the state has enough protections — from state government oversight to ensuring the company has enough money in reserve to address any harm caused by a spill".[15] Iowa state laws require pipeline owners to have only a $250,000 reserve fund. The Iowa chapter of the Sierra Club is "worried about the rights of landowners [...] concerned about [their] Dakota Access LLCs economic projections and whether there are really any benefits to Iowa."[15] Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement (ICCI) has called the pipeline "all risk and no reward" and the $250,000 surety bond "fiscally irresponsible". It has suggested raising it to at least $1 billion, indexed to inflation, which would match Alaska's precautions of protection.[76]

Environmentalists and Native Americans have expressed their fears that the Missouri River might become contaminated in the event of a spill or leak, jeopardizing a source of drinking and irrigation water that affect thousands of people who depend on clean water.[72][77] They claim that the environmental review that has been performed to analyze the impact of the pipeline on its surroundings was incomplete, claiming that even much smaller, less risky development projects require more rigorous impact analysis than has been completed for the Dakota Access Pipeline.[77] They accuse the US Army Corps of Engineers of hastily approving each stage of the review process and ignoring federal regulations and established treaties between Native American tribes and claim there is a lack of environmental foresight and consideration.[78]

It remains unclear what specifically happens if the pipeline leaks, how residents would know of a leak, why the company asks for a permanent easement of farmland when oil rights can be obtained only for 25 years at a time, who the majority shareholders of Dakota Access are, where Energy Transfer's guarantee of liability for newly established Dakota Access, LLC is, and if it is required to have only a $250,000 bond in case of damages.[48] Sunoco Logistics, the future operator of the pipeline, has spilled crude oil from its onshore pipelines more often since 2010 than any other US pipeline operator, with at least 203 leaks disclosed to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration,[79] with a total of 3406 net barrels of crude oil spilled.

Disturbance of land

(NRCS_Photo_Gallery).jpg)

Farmers are concerned about the disturbance of the land, tiling, soil erosion, and soil quality.[46] Iowa fields contain a lot of drain tiles, which can be damaged. The pipeline company said they would repair any tile damaged during construction and place the pipeline 2 feet (.6 m) below drainage tiles.[9] Some farmers were concerned about soil disturbance, but a Dakota Access spokesman noted that the soil had already been disturbed during the installation of drainage tile in all of the contested farms the pipeline planned to cross.[80] Farmers are also concerned about leaks in the pipeline caused by destabilization in certain areas prone to flooding, which could cause an environmental disaster.[81]

Eminent domain

.jpg)

Landowners across Iowa have expressed concern about the implications of allowing the state to use eminent domain to condemn privately-owned land, particularly agricultural land, on behalf of a company that has not demonstrated any substantial public benefit to the residents of Iowa.[13] In March 2015, a Des Moines Register poll found that while 57% of Iowans supported the Dakota Access Pipeline, 74% were opposed to the use of eminent domain condemnation on behalf of a private corporation.[82]

For pipelines, eminent domain is most often invoked to grant a legal "right of way" easement for a certain tract of land with a parcel owned by a private landowner(s) as is necessary for the pipeline to pass through the parcels along its route. While many people believe the invocation of "eminent domain" inherently means land is being taken away completely from landowners,[83][84] landowners do retain ownership of property affected by a pipeline right of way - however, those landowners lose certain rights to the portion of their property encumbered by the easement, including the right to freely use that portion of their property. Because US law requires landowners receive "just compensation" when eminent domain is invoked, landowners whose property rights are affected by the pipeline are compensated for the long-term use of their land, and they are paid for the loss of the current crop on farmland, replacement of fences, and re-seeding of grass.[85][86] When a landowner voluntarily enters an easement agreement granting a right of way for the pipeline in exchange for compensation, the easement is called a voluntary easement.

In August 2016, the pipeline's operator stated that it had already executed easement agreements with 99% of the landowners whose properties lie along the four-state route and, with regards to the landowners along the pipeline's route in Iowa, 99% had entered voluntary easements.[87]

Tribal opposition

The Meskwaki tribe opposes the Bakken pipeline through Iowa for numerous reasons; tribal chairwoman Judith Bender told the Iowa Utilities Board that she is concerned that the Bakken pipeline could be used as a replacement if the Keystone XL pipeline is not built.[5] The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe have also stated their opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline on the grounds that the pipeline and its construction threatens the tribe's "way of life, [their] water, people, and land".[88] The decision to reroute the pipeline closer to the reservation was described by Jesse Jackson and other critics as "environmental racism".[89] According to the statement by Alvaro Pop Ac, Chair of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, “the project was proposed and planned without any consultation with the Standing Rock Sioux or others that will be affected by this major project.”[90] According to the U.S. Army Corps data there had been 389 meetings with more than 55 tribes, including nine meetings with The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.[91]

Political ties

According to his federal disclosure forms, filed in May 2016, President-elect Donald Trump held between $15,000 and $50,000 in stock in Energy Transfer Partners – down from $500,000 to $1 million in 2015 – and between $100,000 and $250,000 in Phillips 66. This creates a conflict of interest when making presidential decisions affecting the pipeline project. The senior Democrat on the Public Resources Committee, Raul Grijalva, called this appearance of conflict of interest "disturbing".[92] The Washington Post reported that Trump sold off his shares in Energy Transfer Partners in the summer of 2016.[93]

Trump is also indirectly linked to the project because Energy Transfer Partners CEO Kelcy Warren contributed $103,000 to the Trump campaign.[94][95] Trump has said that he supports the completion of the pipeline project. According to his transition team this position "has nothing to do with his personal investments and everything to do with promoting policies that benefit all Americans."[96]

In 2013, Iowa Governor Terry Branstad held a campaign fundraiser in Houston. He has subsequently said that he was unaware of Energy Transfer Partners pipeline proposal.[97] Texas governor Rick Perry, who is a close friend of Branstad and who has helped him draw donors,[98] is on ETP's board of directors.[99] A former Branstad re-election campaign staffer, Susan Fenton, who is now the director of government affairs with the Des Moines public relations firm LS2, is handling public relations for Energy Transfer.[19]

Protests

Many Sioux tribes say that the pipeline threatens the Tribe’s environmental and economic well-being, and would damage and destroy sites of great historic, religious, and cultural significance. Protests at pipeline construction sites in North Dakota began in the spring of 2016 and drew indigenous people, calling themselves water protectors and land defenders,[100] from throughout North America as well as many other supporters, creating the largest gathering of Native Americans in the past hundred years.[101]

In April 2016, a Standing Rock Sioux elder established a camp near the Missouri River at the site of Sacred Stone Camp, located within the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, as a center for cultural preservation and spiritual resistance to the pipeline, and over the summer the camp grew to thousands of people.[102] In July, ReZpect Our Water, a group of Native American youth, ran from Standing Rock in North Dakota to Washington, DC to raise awareness of what they perceive as a threat to their people's drinking water and that of everyone who relies on the Missouri and Mississippi rivers for drinking water and irrigation.[9][68]

While the protests have drawn international attention and have been said to be "reshaping the national conversation for any environmental project that would cross the Native American land",[103] there was limited mainstream media coverage of the events in the United States until early September.[104] At that time, construction workers bulldozed a section of land that tribal historic preservation officers had documented as a historic, sacred site, and when protesters entered the area security workers used attack dogs, which bit at least five of the protesters. The incident was filmed and viewed by several million people on YouTube and other social media.[105][106][107][108] In late October, armed soldiers and police with riot gear and military equipment cleared an encampment that was directly in the proposed pipeline's path.[109][110]

On November 15, protesters in Chicago, Los Angeles, Manhattan, Denver, and other cities held protests against the pipeline in a coordinated protest which organizers called a "National Day of Action."[111][112] As of December 2016, the protest at Sacred Stone Camp is ongoing.

See also

- List of natural gas pipelines in North America

- List of oil pipelines in North America

- List of oil refineries in North America

- Pipeline transport

Notes

- ↑ Land marked as "unceded" on this map is not on the Standing Rock reservation and is owned by private citizens and other entities.

References

- ↑ Official "Dakota Access Pipeline" project maps; Energy Transfer.

- ↑ Bakken Pipeline Map and Construction Progress; Nitin Gadia. (unofficial website)

- ↑ Official "Dakota Access Pipeline" project maps; Energy Transfer.

- ↑ Bakken Pipeline Map and Construction Progress; Nitin Gadia. (unofficial website)

- 1 2 William Petroski (March 16, 2015). "Meskwaki tribe opposes Bakken oil pipeline through Iowa". USA Today. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ↑ Harte, Julia (October 5, 2016). "Federal appeals court hears arguments over Dakota Access pipeline". Reuters. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ Richardson, Valerie (November 26, 2016). "U.S. govt. sets deadline for Dakota Access Pipeline protesters to leave federal land". The Washington Times. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

The four-state project is 87 percent complete.

- ↑ "Dakota Access Pipeline". Energy Transfer. 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Petroski, William (August 25, 2014). "Should farmers make way for the Bakken pipeline?". Press Citizen. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ↑ Healy, Jack (2016-08-26). "North Dakota Oil Pipeline Battle: Who's Fighting and Why". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-11-27.

- 1 2 "Dakota Access Pipeline. Overview". Dakota Access, LLC. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Chelsea Keenan (October 1, 2014). "Texas energy company releases more details on pipeline". Cedar Rapids Gazette. SourceMedia, Investcorp. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- 1 2 Petroski, William (February 9, 2016). "296 Iowa landowners decline Bakken pipeline". Des Moines Register. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ↑ Donnelle Eller (November 12, 2014). "Pipeline could bring $1.1 billion to Iowa". Des Moines Register. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Douanne Eller (December 4, 2014). "Unlikely allies join to fight pipeline project". Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ↑ PMHSA (January 2, 2014). "Preliminary Guidance from OPERATION CLASSIFICATION" (Safety Alert). Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ Petroski, William (July 7, 2014). "Bakken oil trains run through Iowa". The Des Moines Register. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Illinois oil train derailment involved safer tank cars". gmtoday.com. Associated Press. March 6, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

As of June of last year, BNSF was hauling 32 Bakken oil trains per week through the surrounding Jo Daviess County, according to information disclosed to Illinois emergency officials. ... According to the Association of American Railroads, oil shipments by rail jumped from 9,500 carloads in 2008 to 500,000 in 2014, driven by a boom in the Bakken oil patch of North Dakota and Montana, where pipeline limitations force 70 percent of the crude to move by rail.

- 1 2 3 Gavin Aronsen (October 28, 2014). "Energy Transfer, Phillips 66 partner on Iowa pipeline". Ames Tribune.

- ↑ Gopinath, Swetha; Erman, Michael (30 April 2012). "Energy Transfer Partners to buy Sunoco for $5.35 billion". Reuters. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ↑ Cryderman, Kelly (2016-08-02). "Enbridge, Marathon Petroleum buy Bakken pipeline stake for $2-billion". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ↑ Penty, Rebecca (2016-08-03). "Enbridge, Marathon Agree to Buy $2 Billion Bakken Pipe Stake". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ↑ McCarthy, Shawn (2016-10-31). "Enbridge remains set on Dakota Access pipeline stake". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ↑ Gallon, Kurt (2016-08-08). "Energy Transfer Partners, Sunoco Logistics Announced Stake Sale". Market Realist. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- ↑ "Who's Investing in the Dakota Access Pipeline? Meet the Banks Financing Attacks on Protesters". Democracy Now!. September 6, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Norway's biggest bank may reconsider Dakota Access funding". CBC News. November 8, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ↑ Geiger, Julianne (November 7, 2016). "Another Setback For DAPL As Norwegian Bank Rethinks Funding". oilprice.com. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ↑ Tchekmedyian, Alene; Etehad, Melissa (2016-11-01). "2 years of opposition, 1,172 miles of pipe, 1.3 million Facebook check-ins. The numbers to know about the Standing Rock protests". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ↑ Sack, Carl (November 2, 2016). "A #NoDAPL Map". Huffington Post. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ↑ Mike Nowatzki (August 30, 2014). "'Stealth' North Dakota Bakken oil pipeline project faces fight". Pioneer Press. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ↑ MacPherson, James (November 3, 2016). "If Dakota Access pipeline were to move, where?". Associated Press. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ↑ Evans, Bo (August 18, 2016). "ND PSC says Dakota Access Pipeline will not come into physical contact with Missouri River". KFYR TV. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ↑ Dakota Access Pipeline. Environmental assessment: Dakota Access Pipeline Project, crossings of flowage easements and federal lands (Report). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha District. p. 385. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ↑ Connie Sieh Groop (September 15, 2014). "Bakken pipeline would cross northeastern South Dakota to get to Illinois". Aberdeen News. Schurz Communications. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- 1 2 William Petroski (July 10, 2014). "Oil pipeline across Iowa proposed". Des Moines Register. Gannett Company. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- 1 2 "Sept 30th DAPL meeting with SRST". youtube. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. September 30, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

from 5:48 (evocation of treaty boundaries: Fort Laramie Treaties (1851 and 1868) and standing resolution from 2012). Afterwards, Chuck Frey (VP of ETP) makes a presentation of the DAPL project.

- 1 2 3 4 5 William Petroski, Iowa board struggles with pipeline decision, Des Moines Register, 12 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 William Petroski Bakken pipeline secures 82 percent of Iowa land parcels Des Moines Register, March 11, 2016

- ↑ William Petroski (October 14, 2014). "Branstad won't stop Bakken oil pipeline through Iowa". Des Moines Register. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ↑ Iowa Utilities Board (n.d.). "Docket Summary for Docket HLP-2014-0001". Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Two county Farm Bureaus to host crude oil pipeline webinar". Illinois Farm Bureau. February 6, 2015. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Search". Illinois Commerce Commission. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ↑ Rod Boshart (December 1, 2014). "Iowa Iowa oil pipeline meetings start today". The Gazette, Cedar Rapids.

- 1 2 Joyce Russell (December 2, 2014). "Landowners Question Bakken Pipeline". Iowa Public Radio. NPR.org. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ↑ Associated Press (December 1, 2014). "Concerns voiced at oil pipeline meeting in S.E. Iowa".

- 1 2 Rachael Krause (December 1, 2014). "Hundreds Pack Inside Sioux Center Meeting On Proposed Dakota Access Pipeline Project". SiouxLandMatters.com. Nexstar Broadcasting, Inc. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ↑ Mark Tauscheck (December 3, 2014). "Iowans pack meeting on new oil pipeline". KCCI-TV. Des Moines Hearst Television Inc. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- 1 2 Megan Naylor (December 5, 2014). "Oil pipeline plan meets with BV resistance". The Daily Reporter. Northwest Iowa Publishing. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ↑ William Petroski (January 20, 2015). "Bakken pipeline OK requested; setting up Iowa showdown". Des Moines Register. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ↑ Jon Lloyd Proposed Bakken pipeline construction requires at least two DNR permits, Boone News Republican, (GateHouse Media, Inc.), 7 February 2015

- ↑ William Petroski (April 28, 2015). "Iowa bills place hurdles for Bakken pipeline, powerline". Des Moines Regicter. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ O. Kay Henderson (May 11, 2015). "Southeast Iowa landowner accuses pipeline agent of improper offer". RadioIowa. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ↑ Amy Mayer. Public Voices Support And Oppose Bakken Pipeline Across Iowa, Iowa Public Radio, 12 November 2015

- ↑ Lauren Donovan (January 1, 2016). "Dakota Access pipeline files condemnation lawsuits". Bismarck Tribune. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ William Petroski "Iowa regulator won't step down from pipeline case", Des Moines Register, 18 February 2016

- ↑ Kim St. Onge IUB announces decision on oil pipeline KCCI, March 9, 2016

- 1 2 William Petroski, Bakken pipeline firm seeks expedited construction permit Des Moines Register, March 17, 2016

- 1 2 William Petrowski (May 27, 2016). "Tribal land issues block Bakken pipeline in Iowa". Des Moines Register. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ↑ William Petroski (May 20, 2016). "Iowa farmers sue to block use of eminent domain for Bakken pipeline". Des Moines Register. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ William Petrowski (June 6, 2016). "Despite critics, Bakken pipeline gets go-ahead in Iowa". Des Moines Register. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ↑ Pat Curtis (31 August 2016). "Bakken oil pipeline protesters arrested in Boone". Radio Iowa. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ Petroski, William (August 1, 2016). "Nearly $1 million in arson reported on Bakken pipeline project". Des Moines Register.

- ↑ Aguirre, Joey (October 17, 2016). "Dakota Access offers $100,000 for information leading to arson conviction". Des Moines Register.

- ↑ Petroski, William (June 20, 2016). "Bakken pipeline will run under sacred tribal site". Des Moines Register. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- ↑ The Seattle Times staff (October 26, 2016). "Live updates from Dakota Access Pipeline protests: 'It will be a battle here'". The Seattle Times. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ↑ Moyers, Bill (September 9, 2016). "What You Need to Know About the Dakota Access Pipeline Protest". Common Dreams. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- 1 2 "Frequently Asked Questions DAPL". US Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha District. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- 1 2 Amundson, Barry (July 29, 2016). "Standing Rock tribe sues over Dakota Access pipeline permits". Grand Forks Herald. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Statement Regarding the Dakota Access Pipeline". Headquarters U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- ↑ Michael Leland, Iowa Public Radio (15 September 2016). "Bakken pipeline opposition presents petitions to U.S. Justice Department". Radio Iowa. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ Hersher, Rebecca. "Obama: Army Corps Examining Possible Rerouting Of Dakota Access Pipeline". National Public Radio. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- 1 2 Dawson, Chester; Maher, Kris (October 12, 2016). "Fight Over Dakota Access Pipeline Intensifies; Company behind the project expects final approval; opponents vow to continue effort". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ↑ Stephanie Januchowski-Hartley; Anne Hilborn; Katherine C. Crocker; Asia Murphy. "Scientists stand with Standing Rock". Science (6307). p. 1506. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ↑ Januchowski-Hartley, PhD, Stephanie (September 2016). "DAPL Scientist Sign-On Letter" (PDF). srjanuchowski-hartley.com. self-published. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ Carolyn Raffensperger (December 5, 2014). "A Legal and Political Analysis of the Proposed Bakken Oil Pipeline in Iowa". SEHN. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Nathan Malachowski (January 17, 2015). "Branstad bullying Legislature over pipeline". Des Moines Register. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- 1 2 Anonymous (August 1, 2016). "Standing Rock Sioux take action to protect culture and environment from massive crude oil pipeline". Earth Justice. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ↑ Yan, Holly (October 28, 2016). "Dakota Access Pipeline: What's at stake?". CNN. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Sunoco, behind protested Dakota pipeline, tops U.S. crude spill charts". Reuters. 2016-09-23. Retrieved 2016-11-02.

- ↑ Hardy, Kevin (August 24, 2016). "Dakota Access pipeline wrecking soil, farmers complain". Des Moines Register.

- ↑ Lloyd, Jon (November 15, 2014). "Pipeline meeting to take place next month in Boone". Boone News Republican. Stephens Media LLC. Archived from the original on 2015-01-12. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Iowa Poll: Iowans back energy projects, but oppose eminent domain". www.desmoinesregister.com. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ For-Profit Pipelines Are Growing And So Are Eminent Domain Battles; Think Progress; June 7, 2016.

- ↑ Invoking power of eminent domain, gas industry runs roughshod over private property; State Impact NPR; May 10, 2016.

- ↑ Sample of an actual right-of-way agreement; Pipeline Safety Trust.

- ↑ Landowner’s Guide to Pipelines; Pipeline Safety Trust.

- ↑ "August 2016: Iowa Progress Report" (PDF). Energy Partners. Dakota Access, LLC. August 9, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ↑ Archambault II, Dave (August 15, 2016). "Call to Action of Indigenous People's" (PDF). Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Retrieved November 15, 2016 – via Stand with Standing Rock.

- ↑ Thorbecke, Catherine (4 November 2016). "Why Previously Proposed Route for Dakota Access Pipeline Was Rejected". ABC News. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ↑ Kerpen, Phil (2016-09-02). "UN Joins Green Group Activists in Anti-Energy Protest to Block N. Dakota Pipeline". CNSNews.com. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ↑ Medina, Daniel A. (2016-09-13). "Sioux's Concerns Over Pipeline Impact on Water Supply 'Unfounded,' Company Says". NBC News. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ↑ "Trump's stock in Dakota Access pipeline raises concerns". Al Jazeera. 2016-11-25. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- ↑ Mufson, Steven (23 November 2016). "Trump dumped his stock in Dakota Access pipeline owner over the summer". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- ↑ Hampton, Liz; Volcovici, Valerie (2016-11-25). "Top executive behind Dakota Access has donated more than $100,000 to Trump". Reuters. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- ↑ Milman, Oliver (October 26, 2016). "Dakota Access pipeline company and Donald Trump have close financial ties". The Guardian. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ↑ Volcovici, Valerie (2016-12-01). "Trump supports completion of Dakota Access Pipeline". Reuters. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ↑ William Petroski (July 14, 2014). "Branstad undecided on Iowa oil pipeline plans". The Des Moines Register.

- ↑ Noble, Jason (29 May 2014). "Rick Perry draws donors for Terry Branstad in Ames". The Des Moines Register. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ Sammon, Alexander (12 August 2016). "The Government Quietly Just Approved This Enormous Oil Pipeline". Mother Jones. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ "#NoDAPL: Land Defenders Disrupt Gubernatorial Debate, Shut Down 5 Construction Sites". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ↑ "Life in the Native American oil protest camps". BBC News. 2 September 2016.

- ↑ Bravebull Allard, LaDonna (September 3, 2016). "Why the Founder of Standing Rock Sioux Camp Can't Forget the Whitestone Massacre". Yes! Magazine. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ↑ Liu, Louise (September 13, 2016). "Thousands of protesters are gathering in North Dakota — and it could lead to 'nationwide reform'". Business Insider. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ↑ Gray, Jim (September 8, 2016). "Standing Rock: The Biggest Story That No One's Covering". Indian Country Today Media Network. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ↑ "VIDEO: Dakota Access Pipeline Company Attacks Native American Protesters with Dogs and Pepper Spray". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ↑ McCauley, Lauren (September 5, 2016). "'Is That Not Genocide?' Pipeline Co. Bulldozing Burial Sites Prompts Emergency Motion". Common Dreams.

- ↑ Staff, ICTMN (September 4, 2016). "What Dakota Access Destroyed: Standing Rock Former Historic Preservation Officer Explains What Was Lost [Video]". Indian Country Today Media Network. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ↑ Manning, Sarah Sunshine (September 4, 2016). "'And Then the Dogs Came': Dakota Access Gets Violent, Destroys Graves, Sacred Sites". Indian Country Today Media Network.com. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ↑ Silva, Daniella (October 27, 2016). "Dakota Access Pipeline: More Than 100 Arrested as Protesters Ousted From Camp". NBC News. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Developing: 100+ Militarized Police Raiding #NoDAPL Resistance Camp Blocking Pipeline's Path". Democracy Now!. October 27, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Dakota Access Pipeline Protests Spread to 300 Cities as Pipeline Owner Sues to Continue Construction". Democracy Now. November 16, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ↑ Daniel A. Medina; Chiara Sottile (November 16, 2016). "Scores Arrested in Dakota Access Pipeline Protests Nationwide". NBC news. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

External links

- Dakota Access Pipeline - Official Website - Energy Transfer

- Dakota Access Pipeline - Project Maps - Energy Transfer

- Frequently Asked Questions DAPL US Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha Division

- SRS Tribal Council Meeting (Sept. 2014) audio. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe meeting with DAPL representatives

- Combined application of Dakota Access LLC for a Waiver or Reduction of Procedures and Time Schedules and for a Corridor Certificate and Route Permit Dakota Access, LLC (Dec. 2014)

- Map of Oil and Natural Gas Pipelines in the United States (Sept. 2015) - Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration

- Memorandum Opinion of "Standing Rock Sioux Tribe vs U.S. Army Corp of Engineers" (Sept. 2016) - United States District Court

- Environmental assessment: Dakota Access Pipeline Project, crossings of flowage easements and federal lands Dakota Access, LLC; US Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha Division