Vickers VC10

| VC10 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Royal Air Force VC10 K3 tanker in 2000. | |

| Role | Narrow-body jet airliner and aerial refueling tanker |

| Manufacturer | Vickers-Armstrongs |

| First flight | 29 June 1962 |

| Introduction | BOAC, 29 April 1964 |

| Retired | Royal Air Force, 20 September 2013 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | BOAC East African Airways Ghana Airways Royal Air Force |

| Produced | 1962–1970 |

| Number built | 54 |

| Unit cost |

£1.75 million |

The Vickers VC10 is a long-range British airliner designed and built by Vickers-Armstrongs (Aircraft) Ltd and first flown at Brooklands, Surrey, in 1962. The airliner was designed to operate on long-distance routes from the shorter runways of the era and commanded excellent hot and high performance for operations from African airports. The performance of the VC10 was such that it achieved the fastest crossing of the Atlantic by a jet airliner, a record still held to date for a sub-sonic airliner, of 5 hours and 1 minute;[1] only the supersonic Concorde was faster. The VC10 is often compared to the larger Soviet Ilyushin Il-62, the two types being the only airliners to use a rear-engined quad layout; the smaller Lockheed JetStar also had this engine arrangement.

Although only a relatively small number of VC10s were built, they provided long service with BOAC and other airlines from the 1960s to 1981. They were also used from 1965 as strategic air lifters for the Royal Air Force, and ex-passenger models and others were used as aerial refuelling aircraft. The 50th anniversary of the first flight of the prototype VC10, G-ARTA, was celebrated with a "VC10 Retrospective" Symposium and the official opening of a VC10 exhibition at Brooklands Museum on 29 June 2012. The type was retired from RAF service on 20 September 2013.[2] It has been succeeded in the aerial refuelling role by the Airbus Voyager. VC10K3 ZA147 performed the final flight of the type on 25 September 2013.

Design and development

Background

Although privately owned, Britain's aviation industry had been government-managed in practice, particularly during the Second World War. Design and manufacture of transport aircraft had been abandoned to concentrate on production of combat aircraft with Britain's transport aircraft needs being met by the provision of US aircraft through Lend-Lease. In 1943, the Brabazon Committee introduced command economy-style principles into the industry, specifying a number of different types of airliners that would be required for the post-war years, though it assumed that US dominance in transport aircraft would translate into leadership in long range airliners and conceded in principle that the industry might have to cede the long-range market to US makers.

During the 1950s, the government required the aviation industry to consolidate: in consequence only two engine makers were left by 1959: Rolls-Royce and Bristol Siddeley. In 1960, the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) encompassed Vickers, Bristol and English Electric's aviation interests, Hawker Siddeley built on de Havilland's heavy aircraft experience and Westland consolidated helicopter manufacture.[3] The British government also controlled route-licensing for private airlines and also oversaw the newly established publicly owned British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) long-range and British European Airways (BEA) short and medium-range airlines.

In 1951, the Ministry of Supply asked Vickers-Armstrongs to consider a military troop/freight development of the Valiant V bomber with trans-Atlantic range as a successor to the de Havilland Comet.[4] The concept interested BOAC, who entered into discussion with Vickers and the RAF.[4] In October 1952, Vickers were contracted to build a prototype which they designated the Type 1000 (Vickers V-1000), followed in June 1954 by a production order for six aircraft for the RAF.[4] The planned civil airliner was known as the VC7 (the seventh Vickers civil design).[5][6] Development was prolonged by the need to meet the RAF's requirements for short take-off and a self-loading capability.[5] Work started on the prototype but by 1955 the aircraft's increased weight required a more powerful engine, causing BOAC to question the engine development cycle. In 1955, the government cancelled the RAF order in a round of defence cuts.[5] Vickers and the Ministry of Supply hoped that BOAC would still be interested in the VC7 but they were reluctant to support the production of another British aircraft following delays in the Britannia programme and the crashes involving the de Havilland Comet.[5]

Concept

Though BOAC had ordered modified Comet 4s, it viewed the type as an intermediate rather than a long term type. In 1956, BOAC ordered 15 Boeing 707s. These were oversized and underpowered for BOAC's medium-range Empire (MRE) African and Asian routes, which involved destinations with "hot and high" airports that reduced aircraft performance, notably between Karachi and Singapore, and could not lift a full load from high-altitude airports like Kano or Nairobi. Several companies proposed a suitable replacement. De Havilland offered the DH.118, a development of the Comet 5 project while Handley Page proposed the HP.97, based on their V bomber, the Victor. After carefully considering the routes, Vickers offered the VC10.[7] Crucially, Vickers was the only firm willing to launch its design as a private venture, instead of relying on government financing.[8]

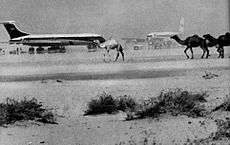

The VC10 was a new design but used some production ideas and techniques, as well as the Conway engines, developed for the V.1000 and VC7. It had a generous wing equipped with wide chord Fowler flaps and full span leading edge slats for good take-off and climb performance; its rear engines gave an efficient clean wing and reduced cabin noise.[9] The engines were also further from the runway surface than an underwing design, an important factor in operations from rough runways such as those common in Africa; wide, low-pressure tyres were also adopted with this same concern in mind.[10] The VC10 was capable of landing and taking off at slower speeds than the rival 707 and its engines could produce considerably more thrust, providing good 'hot and high' performance, and was considered to be a safer aircraft.[11]

The onboard avionics and flight-deck technology was extremely advanced, a quadruplicated automatic flight control system (a "super autopilot") was intended to enable fully automatic zero-visibility landings.[12] Capacity was up to 135 passengers in a two-class configuration. Vickers designer Sir George Edwards is said to have stated that this plane was the sole viable option unless he were to reinvent the 707 and, despite misgivings on operating cost, BOAC ordered 25 aircraft. Vickers calculated that it would need to sell 80 VC10s at about £1.75 million each to break even so, apart from BOAC's 25, another 55 remained to be sold. Vickers offered a smaller version, the VC11, to BEA for routes like those to Athens and Beirut but this was rejected in favour of the Hawker Siddeley Trident.

Production and order problems

Vickers revamped its production plans to try to achieve break-even point with 35 sales at £1.5 million each, re-using jigs from the Vickers Vanguard. On 14 January 1958, BOAC increased its order to 35, with options for a further 20 aircraft, the largest civil order ever placed in Britain at that time;[13][14] these were to have smaller 109-seat interiors and more first-class seating. As the BOAC order alone reached the break-even point, the reuse of Vanguard jigs was abandoned and new production jigs made. To offer greater economy, Vickers began work on the Super 200 development of the VC10 with more powerful Conway engines and a 28 feet (8.1 m) longer fuselage offering up to 212 seats, 23 more than the Boeing 707–320 series.[15][16]

By January 1960, Vickers was experiencing financial difficulties and was concerned that it would not be able to deliver the 35 VC10s without making a loss.[17] It offered to sell ten Super 200s to BOAC at £2.7 million each only to find that BOAC was unconvinced it had a role for the already ordered 35 VC10s and doubted the airline's ability to fill all 200 seats.[16] The whole project looked to be facing cancellation prior to government intervention, supporting Vickers with an order for Super 200s being placed on 23 June 1960.[18] The Super 200 extension was cut down to 13 ft (3.9 m) for the finalised Super VC10 (Type 1150), the original design retrospectively becoming the Standard VC10 (Type 1100).[19]

In accordance with its contracts with Vickers, in May 1961, BOAC amended its order to 15 Standard and 35 Super VC10s, eight of the Supers having a new combi configuration with a large cargo door and stronger floor; in December the order was reduced again to 12 Standards. By the time deliveries were ready to begin in 1964, airline growth had slowed and BOAC wanted to cut its order to seven Supers. In May, the government intervened, placing an order for VC10s as military transports to absorb over-production. This lengthy, well-publicised trouble eroded market confidence in the type.[19][20] BOAC chairman Gerard d'Erlanger and managing director Sir Basil Smallpeice resigned, defending the opinion that the airline was a profit-making company, not a sponsor of indigenous aircraft. BOAC's incoming chairman Sir Giles Guthrie was also anti-VC10; he proposed that the Vickers programme be shelved in favour of more 707s.

Development and production

The prototype Standard, G-ARTA, rolled out of the Weybridge factory on 15 April 1962. On 29 June, after two months of ground, engine and taxi tests, it was first flown by Vickers' chief test pilot G R 'Jock' Bryce, co-pilot Brian Trubshaw and flight engineer Bill Cairns from Brooklands to Wisley for further testing.[21] By the end of the year, two more aircraft had been flown. Flight tests revealed a serious drag problem, which was addressed via the adoption of Küchemann wingtips and "beaver tail" engine nacelle fairings, as well as a redesigned basal rudder segment for greater control effectiveness; these aerodynamic refinements considerably elongated the testing process.[22] The certification programme included visits to Nairobi, Khartoum, Rome, Kano, Aden, Salisbury(Harare) and Beirut. A VC10 flew across the Atlantic to Montreal on 8 February 1964.

By this point, seven of the original 12 Standards were complete and the production line was preparing for the Supers. A Certificate of Airworthiness was awarded on 23 April 1964 and the plane was introduced to regular passenger service between London and Lagos on 29 April.[23][24] By the end of 1964, all production requirements had been fulfilled; Vickers (now part of BAC) retained the prototype. The first Super VC10 was first flown from Brooklands on 7 May 1964. Although the Super was ostensibly a minor development of the Standard with an extra fuel-tank in the fin, testing was prolonged by the need to move each engine pair 11 in (27 cm) outboard as well as up and giving them a 3-degree twist.[25] This redesign resolved tailplane buffeting and fatigue issues incurred by operating the thrust reversers. The two inboard engines could have thrust reversers installed (such as on military VC10s), matching the 707. There was 3.0% more wing area with the leading edge extension reducing aspect ratio and wing root thickness/chord ratios, improving low speed lift and reduced high Mach drag.

Later VC10 developments included the testing of a large main-deck freight-door and fitting new wing leading edges featuring a part-drooped, four-per-cent chord extension over the inboard two-thirds and a drooped, extended-chord wing-tip that allowed more economical high-altitude flying. (This mimicked the 1961 aerodynamics of the similar-looking but significantly different Il-62.) Further developments proposed included freighter versions, one with front-loading like the C-124 Globemaster II. Efforts focused on getting a BOAC order for a 250-seat "VC10 Superb", a move away from the VC10's initial MRE role into the area targeted by the DC-8 Super Sixties. The VC10 would have needed an entirely new double-deck fuselage, which raised emergency escape concerns, and the design failed to attract orders.

Operational history

Commercial service and sales

A total of 12 Type 1101 VC10 were purchased in 1964–65, followed by 17 Type 1151 Super VC10 in 1965–69. The VC10 became an immensely popular aircraft in the BOAC fleet, both with passengers and crew, being particularly praised for its comfort and low cabin noise level. BOAC (and later British Airways) obtained higher load factors with the VC10 than with the 707 or any other aircraft of its fleets.[26][27] Operational experience soon resulted in the deletion of the inboard thrust-reversers due to continued tailplane buffeting despite the engine repositioning. One BOAC Super VC10 was lost during the Dawson's Field hijackings in 1970.

Ghana Airways ordered three VC10s in January 1961: two to be fitted with a cargo door, known as Type 1102s. The first was delivered in November 1964 and the second in May 1965: the third was cancelled.[28] Ghana Airways leased one aircraft to Tayaran Assharq Alawsat (Middle East Airlines; MEA), destroyed at Beirut during an Israeli raid in December 1968. The other was retired from service in 1980. MEA also leased the prototype aircraft that Vickers had kept until 1965, leased from Freddie (later Sir) Laker's charter airline.[29]

British United Airways (BUA) ordered two combi versions (Type 1103) in 1964, receiving them in October that year.[30] When BOAC ceased VC10 operations to South America, BUA took them over, purchasing Ghana Airways' cancelled third aircraft in July 1965 (a Type 1103). The prototype aircraft was purchased from Vickers/BAC and converted from Type 1101 to Type 1109 in 1968. It was initially leased to Middle East Airlines but returned to British Caledonian (as BUA had become) in 1969.[31] The prototype was damaged beyond economical repair in a landing accident at Gatwick in 1972 and the others were sold in 1973–74. One saw further service with Air Malawi, being retired in 1979, and another was sold to the Sultan of Oman as VIP transport and is preserved at Brooklands since its retirement in 1987. One aircraft went to the Royal Aircraft Establishment for equipment tests and was retired in 1980.

Nigeria Airways had planned to buy two VC10s but had to cancel the order for financial reasons; they leased a BOAC aircraft from 1969, but it was destroyed in a landing accident at Lagos in November that year.[32] The final VC10 was the one of five Type 1154 Super VC10 built for East African Airways between 1966 and 1970. Of these, one was destroyed in a takeoff accident at Addis Ababa in 1972, and the other four were retired in 1977 and returned to BAC, subsequently being purchased by the RAF. After the last aircraft was delivered in February 1970, the production line closed, 54 airframes having been built. The 707 and Douglas DC-8, with their superior operating economics, had encouraged many of the world's smaller airports to extend their runways, thus eliminating the VC10's main advantage.

Marketing overtures were made elsewhere, particularly in Mexico, Argentina, Lebanon, Thailand, Czechoslovakia, and Romania, often fronted by British politicians.[33] The final serious enquiry for VC10s came from Chinese state airline Zhōngguó Mínyòng (CAAC) in 1971. It was confirmed in 1972 but by then the production equipment had been broken up.[34] Czechoslovakia, Romania and China eventually purchased the Ilyushin Il-62.

BOAC's successor British Airways (BA) began retiring their Super VC10s from trans-Atlantic flights in 1974, mainly due to the 1973 oil crisis, and using them to displace standard VC10s. Ten of the eleven surviving standard models were retired in 1974–75. Of these, five were leased to Tayaran AlKhalij (Gulf Air) until 1977–78 then purchased by the RAF.[35] One was leased to the Government of Qatar for VIP transport until 1981 when it was purchased by the RAF as an instructional airframe. The Government of the United Arab Emirates used another for similar purposes until 1981; it is preserved at Hermeskeil, Germany. The other three were traded in to Boeing as part payment on new aircraft, and were scrapped at Heathrow. The last standard VC10 in BA service, G-ARVM, was retained as a stand-by for the Super VC10 fleet until 1979. It was preserved at RAF Cosford in the British Airways Museum collection; its condition deteriorated after BA withdrew funding, being reduced to a fuselage in 2006 before being moved to the Brooklands Museum.

Retirement of BA's Super VC10 fleet began in April 1980 and was completed the following year. After failing to sell them to other operators, British Airways sold 14 of the 15 survivors to the RAF in May 1981 (one went for preservation at Duxford). The VC10 served its intended market for only one decade and a half. Written down and amortised by the 1970s, it could have continued in airline service much longer despite its high fuel consumption but high noise levels sealed its fate. Hush-kitting the Conways was considered in the late 1970s but rejected on grounds of cost.

Military service

1960s and 1970s

In 1960, the RAF issued Specification 239 for a strategic transport, which resulted in an order being placed by the Air Ministry with Vickers in September 1961 for five VC10s. The order was increased by an additional six in August 1962, with a further three aircraft cancelled by BOAC added in July 1964.[36] The military version (Type 1106) was a combination of the Standard combi airframe with the more powerful engines and fin fuel tank of the Super VC10.[37] It also had a detachable in-flight refuelling nose probe and an auxiliary power unit in the tailcone. Another difference from the civil specification was that all the passenger seats faced backwards for safety reasons.[38]

The first RAF aircraft, designated VC10 C Mk. 1, often abbreviated to VC10 C1, was delivered for testing on 26 November 1965;[39] deliveries to No. 10 Squadron began in December 1966 and ended in August 1968. The VC10s were named after Victoria Cross (VC) medal holders, the names were displayed above the forward passenger door. During the 1960s, the VC10s of No. 10 Squadron operated two regular routes, one to the Far East to Singapore and Hong Kong, and the other to New York.[40] By 1970, roughly 10,000 passengers and 730,000 lb of freight were being carried monthly by the VC10 fleet.[41]

In addition to the strategic transport role, the VC10 routinely served in the aeromedical evacuation and VIP roles. In the VIP role, the aircraft was commonly used by members of the British Royal family, such as during Elizabeth II's bicentennial tour of America, and by several British Prime Ministers, Margaret Thatcher reportedly insisted on flying by VC10.[42][43] The aircraft proved capable of being flown non-stop by two flight crews, enabling several round-the-world flights, one such VC10 circumnavigated the globe in less than 48 hours.[42]

One aircraft (XR809) was leased to Rolls-Royce for flight testing of the RB211 turbofan between 1969 and 1975.[41][44] On return to the RAF, it was discovered that the airframe was distorted, possibly inflicted by an incident in which a thrust reverser unexpectedly engaged during mid-flight in May 1972.[44] It was considered uneconomical to repair and was instead used for SAS training, before being scrapped.

In 1977, studies began into converting redundant commercial VC10s into aerial refuelling tankers;[45] the RAF subsequently issued a contract to British Aerospace to convert five former BOAC VC10s and four former East African Airways Super VC10s,[46] designated VC10 K2 and VC10 K3 respectively. During conversion, extra fuel tanks were installed in the former passenger cabin; these increased the theoretical maximum fuel load to 85 tons/77 tonnes (K2) and 90 tons/82 tonnes (K3), the Super VC10's fin fuel tank making the difference. In practice, the fuel load was capped by the maximum take-off weight before the tanks were full. Both variants featured a pair of wing-mounted refuelling pods and a single centreline refuelling point, known as a Hose Drum Unit (HDU), installed in the rear freight bay; nose-mounted refuelling probes were also fitted.

Conversion of K2, K3 and K4 tankers took place at British Aerospace's Filton site. The K3s had a forward freight door, facilitating the insertion of five upper fuselage tanks in the main fuselage; the K2s lacked forward freight doors, thus a section of the upper fuselage was dismantled to insert the five upper tanks. In the K2 and K3 conversions, extensive floor reinforcement was installed to support the additional weight imposed by the five fuel tanks.

1980s and 1990s

In 1981, 14 former BA Super VC10s were purchased and stored for spare parts. In the early 1990s, to help the VC10 fleet replace the recently retired Handley Page Victor tankers, five of the stored aircraft were converted to VC10 K4 tankers.[47] Shortly after entering service, extensive wing plank corrosion was discovered on the lower wing surfaces; this was attributed mainly to the storage method used prior to conversion, the wing tanks had been defuelled and filled with water as ballast. Extensive wing plank corrosion rectification work, including plank replacement, often took place during major services. The K4 conversions, as with the K2, lacked forward freight doors, thus it was decided that there would be no internal refuelling tanks fitted. The K4 has identical refuelling equipment to the K2 and K3, but lacks the extra fuselage fuel tanks and retains the same fuel capacity as a Super VC10.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, the 13 surviving C1s were equipped with wing-mounted refuelling pods (HDUs) and re-designated as VC10 C1K two-point tanker/transports. No extra tanks were fitted, the fuel load remaining at 80 tons (70 tonnes). The conversions were undertaken by FR Aviation Limited based at Hurn Airport, near Bournemouth.[48] The in-flight refuelling probe was an original feature on the aircraft, but had been removed during the 1970s and 1980s due to lack of use; the probes were refitted prior to the conversion. Replacing the Conway engines with IAE V2500 was studied but was not found to be cost-effective.[49]

In 1982, VC10 C1s formed a part of the airbridge between RAF Brize Norton and Wideawake Airfield on Ascension Island during Operation Corporate, the campaign to retake the Falkland Islands.[50] The VC10 were also used in a more unconventional sense – the Avro Vulcan bombers that participated in Operation Black Buck had been rapidly retrofitted with the Dual Carousel navigation system of the Super VC10s, enabling effective open ocean navigation.[51] A pair of VC10s were also painted with Red Cross markings and used for casualty evacuation from neutral Uruguay during the conflict.[43]

In 1991, 9 K2s and K3s were deployed to bases in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Oman as part of Operation Granby, the UK's contribution to the First Gulf War. A total of 5,000 flight hours across 381 sorties were flown in the theatre, flying both aerial refuelling and logistical missions in support of coalition forces in combat with the occupying Iraqi forces in Kuwait.[43][50] VC10s remained stationed in the region throughout the 1990s, supporting allied aircraft enforcing no-fly zones over parts of Iraq, and during the 1998 Airstrikes on Iraq.[52][53]

During the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, VC10 tankers were stationed at bases in Southern Italy to refuel NATO aircraft in the theatre, as part of Operation Allied Force.[52] The VC10s allowed Tornado GR1 fighter-bombers stationed at RAF Bruggen to conduct long-range strike missions inside targets inside Serbia.[50]

2000s

_Flight_Officer_Paul_Summers_(co_pilot%2C)_Flight_Lt._Mick_Hardwick_(engineer%2C)_and_Squadron_Leader_Kev_Brookes_(navigator)_of_101_Squadron%2C_o.jpg)

In 2001, Oman-based VC10s were used in some of the first missions of the war in Afghanistan, refuelling US carrier-based aircraft carrying out strikes on Afghan targets. The VC10s provided air transport missions in support of British and allied forces stationed in Afghanistan fighting against the Taliban, codenamed Operation Veritas. VC10s remained on long term deployment to the Middle East for twelve years, ending just before the type's retirement.[52]

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq by an American-led coalition, a total of nine VC10s were deployed to the theatre under Operation Telic.[50] In the aftermath of the invasion, multiple VC10s were commonly stationed in Iraq; in addition to logistics operations, more than a thousand casualties of the conflict were evacuated to Cyprus by VC10s.[52] In June 2009, the remaining VC10s were withdrawn from Iraq, along with most other British military assets.[54]

Between 2000 and 2003, the remaining K2s were retired and scrapped. The surviving K3s served as tanker/transports with No. 101 Squadron at Brize Norton, Oxfordshire and the single remaining K4 supported No. 1312 Flight at RAF Mount Pleasant in the Falkland Islands.[55] In January 2010, VC10 passenger operations were temporarily suspended while an airworthiness review was carried out.[56]

Following the 2006 North Korean nuclear test, a pair of VC10s were dispatched to Okinawa, Japan to undertake nuclear debris tests, this unusual task was performed using specialised sampling pods which replace the refuelling pods equipped as standard.[50] During Operation Ellamy, Britain's contribution to the 2011 military intervention in Libya, a small number of VC10s were dispatched to bases in the Mediterranean and were used to refuel NATO strike aircraft being used in the theatre.[57]

The VC10 and Lockheed TriStar tanker/transports were replaced in RAF service by the Airbus A330 MRTT Voyager under the Future Strategic Tanker Aircraft Project.[58][59] The type's final flights in RAF service took place on 20 September 2013, the final refuelling sortie was followed by a tour of the UK.[2][60] On 24 September, ZA150 had its last flight to Dunsfold Aerodrome for preservation at the Brooklands Museum, while ZA147 arrived at Bruntingthorpe on 25 September.

Servicing and support

All servicing of the RAF fleet of VC10s was undertaken at RAF Brize Norton in a purpose-built hangar. Known as "Base Hangar", when built in 1969 it was the largest cantilever-roofed structure in Europe; a quarter of a mile in length with no internal supports. Up to six VC10s could be positioned inside with adequate room remaining for working space around each aircraft.[61] During the late 1980s, plans to move major servicing to RAF Abingdon near to RAF Brize Norton were considered. Abingdon was closed and a new facility was built at RAF St Athan, in South Wales – "1 Air Maintenance Sqn" (1 AMS); the first aircraft to undergo major servicing at the facility entered in January 1993.

After the closure of the British Aerospace factories at Brooklands/Weybridge and Hatfield, responsibility of design and all commercial activity transferred to British Aerospace (now BAE Systems) Manchester, Woodford and Chadderton sites. In the mid-1990s, when the design of detailed components was subcontracted, the design team transferred from Woodford to Chadderton. In 2003, responsibility for the commercial procurement of all spares items was undertaken by BAE Systems, at BAE Systems Samlesbury. The Chadderton site maintained responsibility for the MoD contracts for project managing modifications; major repairs and major maintenance being carried out at RAF St Athan.

Variants

- Commercial

- Vickers V.C.10 Type 1100: Prototype; one built, (one converted to Type 1109)

- BAC VC10 Type 1101: BOAC Standards; up to 35 ordered at various times; 12 built

- BAC Standard VC10 Type 1102: Ghana Airways' Standard combis; three built (one redesignated Type 1103)

- BAC Standard VC10 Type 1103: BUA Standard combis; two built, (one redesignated Type 1102)

- BAC Standard VC10 Type 1104: Nigeria Airways' Standards; two ordered, none built

- BAC Standard VC10 Type 1109: Converted from Type 1100 for lease to Laker Airways

- BAC Super VC10 Type 1150: Generic Super VC10

- BAC Super VC10 Type 1151: BOAC Supers, up to 22 ordered at various times; 17 built

- BAC Super VC10 Type 1152: BOAC Super combi; 13 ordered, none built

- BAC Super VC10 Type 1154: East African Airways' Super combi; five built

- Military

- VC10 C1: RAF designation for the VC10 Type 1106; 14 built, 13 converted to VC10 C1K

- VC10 C1K: RAF designation for 13 VC10 Type 1180 transport/tanker aircraft converted from VC10 C1, 2-point and no maindeck tanks

- VC10 K2: RAF designation for five VC10 Type 1112 inflight-refuelling tankers converted from Type 1101

- VC10 K3: RAF designation for four VC10 Type 1164 inflight-refuelling tankers converted from Type 1154, 3-point and maindeck tanks

- VC10 K4: RAF designation for five VC10 Type 1170 inflight-refuelling tankers converted from Type 1151, 3-point but no maindeck tanks

Operators

Civilian operators

- East African Airways (original operator)

- Ghana Airways (original operator)

- BOAC (Original operator)

- British Airways

- British Caledonian

- British United Airways (original operator)

- Laker Airways

- Rolls-Royce (engine test bed)

Military and government operators

- Oman Royal Flight

- The Government of the United Arab Emirates

- Royal Air Force (original operator)

- No. 10 Squadron RAF

- No. 101 Squadron RAF last operator of the type.

- No. 1312 Flight RAF

- Royal Aircraft Establishment

Accidents and incidents

- On 28 December 1968, Middle East Airways 9G-ABP was destroyed at Beirut Airport in the 1968 Israeli raid on Lebanon.[62]

- On 20 November 1969, Nigeria Airways Flight 825 crashed on landing at Lagos, Nigeria killing all 87 passengers and crew.[62]

- On 27 November 1969, BOAC G-ASGK had a major failure of No.3 engine, debris from that engine damaged No.4 engine causing a fire. A safe overweight landing was made at Heathrow without any casualties.[62]

- On 9 September 1970, BOAC G-ASGN was hijacked, and on 12 September was blown up at Zerqu Jordan, in the Dawson's Field hijackings.[62]

- On 28 January 1972, British Caledonian G-ARTA was damaged beyond economic repair in a landing accident at Gatwick.[62]

- On 18 April 1972, East African Airways Flight 720 5X-UVA crashed on take-off from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia killing 43 of the 107 passengers and crew.[62]

- On 3 March 1974, BOAC G-ASGO was hijacked and landed at Schiphol, Netherlands, where the aircraft was set on fire and damaged beyond economic repair.[62]

- On 21 November 1974, British Airways Flight 870 from Dubai to Heathrow carrying 45 people was hijacked in Dubai, landing at Tripoli for refuelling before flying on to Tunis. The three hijackers demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners, five in Egypt, two in the Netherlands. One hostage was murdered, the hijackers surrendered after 84 hours to Tunisian authorities on 25 November. Captain Jim Futcher was awarded the Queen's Gallantry Medal, the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators Founders Medal, the British Airline Pilots Association Gold Medal and a Certificate of Commendation from British Airways for his actions during the hijacking, returning to fly the aircraft knowing the hijackers were on board.[63]

- On 18 December 1997, Royal Air Force XR806 was damaged beyond economic repair in a ground de-fuelling accident at RAF Brize Norton.[62]

Aircraft on display

- Type 1101 (registration G-ARVF) is on display in United Arab Emirates government colours at the Flugausstellung Hermeskeil at Hermeskeil, Germany.[64]

- Type 1101 (registration G-ARVM) (fuselage only with a comprehensive VC10 Exhibition housed in the rear cabin) at Brooklands Museum, Surrey, England.[65]

- Type 1103 (registration A40-AB, formerly G-ASIX), originally owned by British United Airways before being sold to British Caledonian, it was later sold to the Omani government where it was used from 1974–1987 by the Sultan of Oman as his personal jet. On display in Omani Royal Flight colours at the Brooklands Museum, Surrey, England.[66]

- Type 1151 (registration G-ASGC) is on display in BOAC-Cunard colours at the Imperial War Museum, Duxford, Cambridgeshire, England.[67]

- Type 1180 C1K XR808 "Bob" is to be put on display outside at the Royal Air Force Museum Cosford in 2015.[68]

- Type 1180 C1K XV108 (forward fuselage) on public display at East Midlands Aeropark.

- Type 1164 K3 ZA150 c/n 885 formerly with East African Airways Type 1154 5H-MOG (and the last VC10 built) was delivered to Dunsfold Park, Surrey on 24 September 2013 where it is preserved in ground running condition by Brooklands Museum.[69][70]

- Type 1164 K3 ZA148 c/n 883 formerly with East African Airways Type 1154 5Y-ADA, delivered to the Classic Air Force collection at Newquay, Cornwall, 28 August 2013.[71]

- Type 1170 K4 ZD241 c/n 863 formerly BOAC/BA Type 1151 G-ASGM. Now owned by GJD Services and preserved in ground running condition at Bruntingthorpe Aerodrome.

- Type 1164 K3 ZA147 c/n 882 formerly East African Airways Type 1154 5H-MMT, delivered to Bruntingthorpe Aerodrome in Leicestershire on 25 September 2013. Now owned by GJD Services, it is likely that this aircraft used as spares to help the preservation of ZD241.

Specifications (Model 1101)

Data from Macdonald Aircraft Handbook,[21] Flight International[25]

General characteristics

- Crew: 4 + 3 flight attendants

- Capacity: 151 passengers

- Length: 158 ft 8 in (48.36 m)

- Wingspan: 146 ft 2 in (44.55 m)

- Height: 39 ft 6 in (12.04 m)

- Wing area: 2,851 ft2 (264.9 m2)

- Empty weight: 139,505 lb (63,278 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 334,878 lb (151,900 kg)

- Powerplant: 4 × Rolls-Royce Conway Mk 301 Turbofan, 22,500 lbf (100.1 kN) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 580 mph (933 km/h)

- Range: 5,850 miles (9,412 km)

- Service ceiling: 43,000 ft (13,105 m)

- Wing loading: 110 lb/ft2 (534 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.27

See also

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

Citations

- ↑ "Testing and early days".

- 1 2 "Vickers VC10 jetliners fly last mission from RAF Brize Norton". BBC News. 20 September 2013.

- ↑ Hayward 1983, pp. 41–44.

- 1 2 3 Henderson 1998, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Henderson 1998, p. 6.

- ↑ Hayward 1983, pp. 22–24, 27.

- ↑ Harrison 1965, p. 494.

- ↑ Hayward 1983, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Walker and Henderson 1998, pp. 18–18, 40, 49.

- ↑ Harrison 1965, pp. 495–498.

- ↑ Walker and Henderson 1998, pp. 9–45.

- ↑ Walker and Henderson 1998, pp. 18, 26–27.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1988, p. 468.

- ↑ Goldring, Mary. "Forced Change in the Aircraft Industry." New Scientist, 3(61), 16 January 1958. pp. 10–12.

- ↑ Harrison 1965, p. 495.

- 1 2 Cole 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Hayward 1983, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Hayward 1983, pp. 46–48.

- 1 2 Harrison 1965, pp. 495–496.

- ↑ "Jet – When Britain Ruled The Skies: Episode 2". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2012.

- 1 2 Green 1964, p. 228.

- ↑ Cole 2000, pp. 69, 74.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1988, p. 473.

- ↑ Cole 2000, p. 74.

- 1 2 Harrison 1965, p. 497.

- ↑ Donald 1999, p. 778.

- ↑ Harrison 1965, p. 498.

- ↑ Cole 2000, p. 131.

- ↑ Jackson 1988, p. 233.

- ↑ Cole 2000, p. 129.

- ↑ Walker and Henderson 1998, pp. 76–79.

- ↑ Cole 2000, p. 134.

- ↑ Walker and Henderson 1998, pp. 29–32.

- ↑ Walker and Henderson 1998, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Walker and Henderson 1998, p. 64.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1988, p. 474.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1988, p. 475.

- ↑ "VC10s in RAF service". vc10.net. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ Green 1968, p. 26.

- ↑ Barfield and Wynn 1970, pp. 158–159.

- 1 2 Barfield and Wynn 1970, p. 163.

- 1 2 Barfield and Wynn 1970, p. 159.

- 1 2 3 "RAF to retire VC10s after 50 years." Times of Malta, 18 September 2013.

- 1 2 Norris, Guy. "Weird and Wonderful – Flying Testbeds." Aviation Week, 21 May 2010.

- ↑ Air International October 1980, p. 160.

- ↑ Air International October 1980, p. 159.

- ↑ Barrie 1993, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ "BAe and FR win RAF tanker deal." Flight International, 13 February 1990. p.18

- ↑ Barrie 1993, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 'Aircraft of the RAF Part 2: Vickers VC10' Air International May 2008 pp. 56–60.

- ↑ Rowland White – Vulcan 607

- 1 2 3 4 "No. 101 Squadron." Royal Air Force, Retrieved: 22 March 2013.

- ↑ Barrie 1993, p. 25.

- ↑ "Flypast marks RAF tankers' farewell to Iraq." Oxford Mail, 3 June 2009.

- ↑ Kingsley-Jones, Max (10 July 2012). "FARNBOROUGH: RAF squadron commander details VC10 retirement plans". Flight Daily News.

- ↑ Hoyle, Craig. "Royal Air Force suspends passenger operations with VC10 fleet." Flight International, 19 January 2010.

- ↑ "RAF tanker aircraft keep missions flying over Libya". Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom). 18 July 2011.

- ↑ Barrie 1993, p. 27.

- ↑ Osborne, Tony (29 July 2013). "And Then There Were Three...". Aviation Week.

- ↑ "VC10 – The Final Chapter". Royal Air Force. 19 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ "Brize Norton: Introduction: A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 15." British History Online. 2006, pp. 205–218.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Incidents and Accidents".

- ↑ "Captain Jim Futcher". London: Telegraph. 31 May 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2008.

- ↑ "Flugzeuge Flugausstellung Peter Junior" Flugausstellung Junior, Retrieved: 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Vickers 1101 VC10 G-ARVM (1964)." Brooklands Museum, Retrieved: 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Vickers 1103 VC10 ex G-ASIX/A4O-AB (1964)." Brooklands Museum, Retrieved: 15 March 2013.

- ↑ "Vickers Super VC10 Type 1151 G-ASGC." Duxford Aviation Society, Retrieved: 15 March 2013.

- ↑ "VC10 XR808 prepares for final move to Cosford" 6 May 2015 RAF Museum

- ↑ "‘Queen of the Skies’ retires to Dunsfold Park." Brooklands Museum, 24 September 2013.

- ↑ "Brooklands Museum". www.brooklandsmuseum.com. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- ↑ "Aviation News – Ex-RAF Vickers VC10 K3 ZA148 Joins Classic Air Force Collection." Global Aviation Resource, 28 August 2013.

Bibliography

- Andrews, C.F. and Morgan E.B. Vickers Aircraft since 1908. London:Putnam, 1988. ISBN 0-85177-815-1.

- Barfield, Norman and Humphrey Wynn. Far East Commuter: Britain's Military Jet Transport Service. Flight International, 1970. pp. 157–163.

- Barrie, Douglas. Tanking Up: RAF Refuelling. Flight International, 7 September 1993. pp. 25–27.

- Benn, Tony. The Tony Benn Diaries 1940–1990. Arrow, 1996. ISBN 0-09-963411-2.

- Cole, Lance. Vickers VC10. Ramsbury:Crowood Press, 2000. ISBN 1-86126-231-0.

- Donald, David (editor). The Encyclopedia of Civil Aircraft. London:Aurum Press, 1999. ISBN 1-85410-642-2.

- Green, William. Aircraft Handbook. London:Macdonald & Co., 1964.

- Green, William. The Observer's Book of Aircraft. London. Frederick Warne & Co., 1968.

- Harrison, N.F.G. "The Super VC-10". Flight International, 1 April 1965. pp. 494–498.

- Hayward, Keith. Government and British Civil Aerospace: A Case Study in Post-war Technology Policy, Manchester University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-71900-877-8.

- Hedley, Martin. VC-10. Modern Civil Aircraft Series, London:Ian Allan, 1982. ISBN 0-7110-1214-8.

- Henderson, Scott. Silent, Swift, Superb: the Story of the Vickers VC10. Scoval, ISBN 1-902236-02-5.

- Jackson, A.J. British Civil Aircraft 1919–1972: Volume III. London:Putnam, 1988. ISBN 0-85177-818-6.

- Powell, David. Tony Benn: a Political Life. Continuum Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8264-5699-5.

- Smallpeice, Sir Basil. Of Comets and Queens. Shrewsbury:Airlife, 1981. ISBN 0-906393-10-8.

- "VC 10: Transport to Tanker". Air International, October 1980, Vol 19 No. 4. ISSN 0306-5634. pp. 159–165, 189.

- Walker, Timothy and Scott Henderson. Silent Swift Superb: The Story of the Vickers VC10. Scoval, 1998. ISBN 1-90223-602-5.

- Willis, Dave. "Aircraft of the RAF-Part 2: Vickers VC10". Air International, May 2008, Vol 74 No. 4. ISSN 0306-5634. pp. 56–60.

- The Putnam Aeronautical Review. No.1, March 1989, Putnam.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vickers VC10. |

- Royal Air Force VC10 page

- A little VC10derness – a website dedicated to the VC10

- VC10 British Pathe newsreel footage: (Adobe Flash video)

- "VC10 in the Clear", 1964

- "VC10 Proves Itself", 1965

- "BOAC VC10 Automatic Landing", 1968