Avoirdupois

The avoirdupois system (English pronunciation: /ˌævərdəˈpɔɪz/; abbreviated avdp)[1] is both an updated modern[2] as well as an historic measurement system of weights (using units such as pounds and ounces)[3] that became commonly used in the 13th century, but was updated (1959) to represent, (by law[2]) mass in line with SI based units.

The avoirdupois weight system's general attributes were originally developed for the international wool trade in the Late Middle Ages era when trade was in recovery, and historically based on a physical standardized pound or 'prototype weight' that could be partitioned into 16 ounces.[lower-alpha 1] There were a number of such competing measures, and the fact the avoirdupois pound had three even numbers as multiples (half and half and half again) caused much of its popularity so that the system won out over systems with 12 or ten or 15 subdivisions.[3] The use of this unofficial system gradually stabilized[lower-alpha 2] and evolved with only slight changes in the reference standard or prototype's actual mass.

Over time, the desire to use only a few such scales allowed establishment of value relationships to other commodities metered and sold by weight measurements such as bulk goods (grains, ores, flax) and smelted metals, so gradually became an accepted standard through much of Europe.[3]

In England, Henry VII authorized its use as a standard and Queen Elizabeth I acted three times to ensure a common standard establishing what became the Imperial system of weights and measures.[3] Late in the 19th century various governments acted to redefine their base standards on a scientific basis and establish ratio-metric equations to SI metric system standards.[3] They did not always pick the same equivalencies, though the pound remained very similar; these independent legal actions lead to slight (small fractional) differences in certain quantities, such as the American and Imperial pounds, et al.[3]

In 1959 by international agreement, the definition of such pound and ounce units became standardized among countries using the pound-based mass units.[3] The International Avoirdupois Pound so created is the everyday system of weight used in the United States and is still used to varying degrees in everyday life in the United Kingdom, Canada and some other former British colonies despite the official adoption of the metric system.

An alternative system of mass, the troy system, is generally used for precious materials. The modern definition of the avoirdupois pound is exactly 0.45359237 kilograms.[2][3]

Internationalization and confusions

See Also main articles: pound-force, poundal and pound-mass.

In the avoirdupois system, all units are multiples or fractions of the pound, which is now defined as 0.45359237 kg exactly in most of the English-speaking world since the implementation of the international yard and pound agreement of 1959.[2]

Due to the ambiguous meanings of "weight" as referring to both mass and force, it is sometimes erroneously asserted that the pound is only a unit of force similar to the Newton (unit).[lower-alpha 3]

As can be seen in the table below, a pound-force requires an acceleration to be applied. However, as defined above the pound is a unit of mass, which agrees with common usage.[lower-alpha 4] Similarly, the kilo is a colloquialism spawned by equating the metric kilogram unit of mass and extending it to everyday uses — not uses in science and engineering. Many such uses, would involve accelerations as the table below indicates.

| Base | force, length, time | weight, length, time | mass, length, time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force (F) | F = m⋅a = w⋅a/g | F = m⋅a/gc = w⋅a/g | F = m⋅a = w⋅a/g | |||||

| Weight (w) | w = m⋅g | w = m⋅g/gc ≙ m | w = m⋅g | |||||

| System | BG | GM | EE | M | AE | CGS | MTS | SI |

| Acceleration (a) | ft/s2 | m/s2 | ft/s2 | m/s2 | ft/s2 | Gal | m/s2 | m/s2 |

| Mass (m) | slug | hyl | lbm | kg | lb | g | t | kg |

| Force (F) | lb | kp | lbF | kp | pdl | dyn | sn | N |

| Pressure (p) | lb/in2 | at | PSI | atm | pdl/ft2 | Ba | pz | Pa |

| The systems above left to right are: |

| today the other systems' standards are defined in terms of the SI |

This is usually a confusion of misunderstood pedagogy, or of information reception among those not appreciating the precision of context understood by technically trained parties—part of technical pedagogy is training to consistently apply unit analysis as is shown in the above table.

The above table shows that the definition of the pound depends on the system parameters which are known (the starting point) or simply on the choice of system one wants or needs to work within to satisfy some other criteria driving compatibility.

Etymology

The word avoirdupois is from Anglo-Norman French aveir de peis (later avoir de pois), literally "goods of weight" (Old French aveir, "property, goods", also "to have", comes from the Latin habere, "to have, to hold, to possess property"; de = "from"/"of", cf. Latin; peis = "weight", from Latin pensum).[6][7] This term originally referred to a class of merchandise: aveir de peis, "goods of weight", things that were sold in bulk and were weighed on large steelyards or balances.

Only later did the term become identified with a particular system of units used to weigh such merchandise. The warfare impacted orthography of the day has left many variants of the term, such as haberty-poie and haber de peyse. (The Norman peis became the Parisian pois. In the 17th century de was replaced with du.)[8]

History

The rise in use of the measurement system corresponds to the regrowth of trade during the High Middle Ages after the early crusades, when Europe experienced a growth in towns, turned from the chaos of warlordism to long distance trade, and began annual fairs, tournaments and commerce, by land and sea. There are two major hypotheses regarding the origins of the avoirdupois system. The older hypothesis is that it originated in France.[9] A newer hypothesis is that it is based on the weight system of Florence.[10][3]

The avoirdupois weight system is thought to have come into use in England circa 1300. It was originally used for weighing wool. In the early 14th century several other specialized weight systems were used, including the weight system of the Hanseatic League with a 16-ounce pound of 7200 grains and an 8-ounce mark. However, the main weight system, used for coinage and for everyday use, was based on the 12-ounce tower pound of 5400 grains. From the 14th century until the late 16th century, the systems basis, the avoirdupois pound, the prototype for today's international pound was also known as the 'wool pound' or the avoirdupois wool pound.

The earliest known version of the avoirdupois weight system had the following units: a pound of 6992 grains, a stone of 14 pounds, a woolsack of 26 stone, an ounce of 1⁄16 pound, and finally, the ounce was divided into 16 "parts".[11]

The earliest known occurrence of the word "avoirdupois" (or some variant thereof) in England is from a document entitled Tractatus de Ponderibus et Mensuris or Treatise on Weights and Measures. This document is listed in early statute books under the heading 31 Edward I dated 2 February 1303. More recent statute books list it under Statutes of uncertain date. Scholars nowadays believe that it was probably written between 1266 and 1303.[12] Initially a royal memorandum, it eventually took on the force of law and was recognized as a statute by King Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I.

It was repealed by the Weights and Measures Act of 1824. In the Tractatus, the word "avoirdupois" refers not to a weight system, but to a class of goods, specifically, heavy goods sold by weight, as opposed to goods sold by volume, by count, or by some other method. Since it is written in Anglo-Norman French, this document is not the first occurrence of the word in the English language.[13][14]

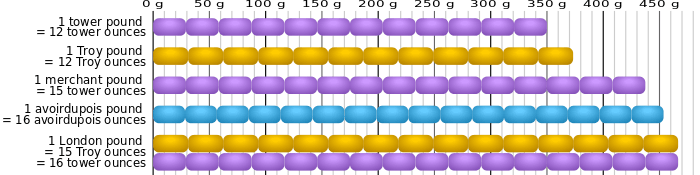

Comparison of the relative sizes of avoirdupois, Troy, tower, merchant and London pounds. |

Towards A Uniformity of Measures

Three major developments occurred during the reign of Edward III (r. 1327-77). First, a statute known as 14o Edward III. st. 1. Cap. 12 (1340) "Bushels and Weights shall be made and sent into every County."[15]

- Original: "& acorde qe deſore en auant vn meſure & vn pois ſoit parmy toute Engleterre & qe le Treſorer face faire certaines eſtandardz de buſſel de galon de poys darreiſne & les face mander en cheſcune countee par la ou tielx eſtandardz ne ſont pas auant ces hures mandez"

- English translation: "(4) it is assented and accorded, That from henceforth one Measure and one Weight shall be throughout the Realm of England; (5) and that the Treasurer cause to be made certain Standards of Bushels, Gallons, of Weights of Auncel, and send the same into every County where such Standards be not sent before this Time;"

The second major development is the statute 25o Edward III. st. 5. Cap. 9. (1350) "The Auncel Weight shall be put out, and Weighing shall be by equal Balance."[16]

- Original: "qe le ſak de leine ne poiſe qe vint & ſys peres & cheſcun pere poiſe quatorze livres"

- English translation: "so that the Sack of Wooll weigh no more but xxvi. Stones, and every Stone to weigh xiv. l."

The third development is a set of 14th-century bronze weights at the Westgate Museum in Winchester, England. The weights are in denominations of 7 pounds (corresponding to a unit known as the clip or wool-clip), 14 pounds (stone), 56 pounds (4 stone) and 91 pounds ( 1⁄4 sack or woolsack).[17][18] The 91-pound weight is thought to have been commissioned by Edward III in conjunction with the statute of 1350, while the other weights are thought to have been commissioned in conjunction with the statutes of 1340. The 56-pound weight was used as a reference standard as late as 1588.[19][20]

A statute of Henry VIII (24o Henry VIII. Cap. 3) made avoirdupois weights mandatory.

In 1588 Queen Elizabeth increased the weight of the avoirdupois pound to 7000 grains and added the troy grain to the avoirdupois weight system. Prior to 1588, the "part" ( 1⁄16) was the smallest unit in the avoirdupois weight system. In the 18th century, the "part" was renamed "drachm".

Original forms

These are the units in their original Anglo-Norman French forms:[16]

| Unit | Relative value |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| "part" | 1⁄256 | 1⁄16 once |

| once (ounce) | 1⁄16 | |

| livre (pound) | 1 | |

| pere (stone) | 14 | |

| sak de leine (woolsack) | 364 | 26 peres |

Post-Elizabethan

In the United Kingdom, 14 avoirdupois pounds equals one stone. The quarter, hundredweight, and ton equal respectively, 28 lb, 112 lb, and 2,240 lb in order for masses to be easily converted between them and stones. The following are the units in the British or imperial version of the avoirdupois system:

| Unit | Relative value |

Metric value |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| dram or drachm (dr) | 1⁄256 | ≈ 1.772 g | 1⁄16 oz |

| ounce (oz) | 1⁄16 | ≈ 28.35 g | 16 dr |

| pound (lb) | 1 | ≈ 453.6 g | 16 oz |

| stone (st) | 14 | ≈ 6.350 kg | 1⁄2 qr |

| quarter (qr) | 28 | ≈ 12.70 kg | 2 st |

| hundredweight (cwt) | 112 | ≈ 50.80 kg | 4 qr |

| ton (t) or long ton |

2240 | ≈ 1016 kg | 20 cwt |

Note: The plural form of the unit stone is either stone or stones, but stone is most frequently used.

American customary system

The 13 British colonies in North America used the avoirdupois system, but continued to use the British system as it was, without the evolution that was occurring in Britain in the use of the stone unit. In 1824 there was landmark new weights and measures legislation in the United Kingdom that the United States did not adopt.

In the United States, quarters, hundredweights, and tons remain defined as 25, 100, and 2000 lb respectively. The quarter is now virtually unused, as is the hundredweight outside of agriculture and commodities. If disambiguation is required, then they are referred to as the smaller "short" units in the United States, as opposed to the larger British "long" units. Grains are used worldwide for measuring gunpowder and smokeless powder charges. Historically, the dram has also been used worldwide for measuring gunpowder charges, particularly for shotguns and large black-powder rifles.

| Unit | Relative value |

Metric value |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| grain (gr) | 1⁄7000 | ≈ 64.80 mg | 1⁄7000 lb |

| dram (dr) | 1⁄256 | ≈ 1.772 g | 1⁄16 oz |

| ounce (oz) | 1⁄16 | ≈ 28.35 g | 16 dr |

| pound (lb) | 1 | ≈ 453.6 g | 16 oz |

| quarter (qr) | 25 | ≈ 11.34 kg | 25 lb |

| hundredweight (cwt) | 100 | ≈ 45.36 kg | 4 qr |

| ton (t) or short ton |

2000 | ≈ 907.2 kg | 20 cwt |

Notes

- ↑ School science curricula, especially empirical physical chemistry courses, often introduce students to careful measurements using a pan balance and standardized weights. These are essentially prototype weight clones.

- ↑ Great trade fairs grew up in various sites in Europe, and their regulation and enforcement would act to define such measures.

- ↑ Examining pound-force units versus Newtons —a units analysis would show:

N=kg • m/s2, a mass • acceleration. Pounds-force needs a similar conversion by a measurement system compatible acceleration (ft/s2), to realize the same configuration:lbf = lbm • ft/s2— this is one form of unit analysis, a check by units making sure one's self is using the proper parameters and equations.

Hint: Doing this sort of check on units has turned many a 'C' into an 'A' on examinations. - ↑ On mass v. weight and common usage: to understand proper contexts, weighing things until just this past century and high quality steel allowed spring scales generally required resorting to a balance measurement using comparison to a standard set of calibrated (known) weights on scales, whether beam balance or pan balance in configuration.

See also

- Apothecaries' system

- Units of measurement in France

- Imperial units

- Troy weight

- United States customary units

- Weighing scales

References

- ↑ United States National Bureau of Standards. "Appendix C of NIST Handbook 44, Specifications, Tolerances, and Other Technical Requirements for Weighing and Measuring Devices, General Tables of Units of Measurement" (PDF). p. C-12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-26.

- 1 2 3 4 United States. National Bureau of Standards (1959). Research Highlights of the National Bureau of Standards. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards. p. 13. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "pound avoirdupois". www.sizes.com/units/pound_avoirdupois.htm. 17 April 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Michael R. Lindeburg (2011). Civil Engineering Reference Manual for the Pe Exam. Professional Publications. ISBN 1591263417.

- ↑ Wurbs, Ralph A, Fort Hood Review Sessions for Professional Engineering Exam (PDF), retrieved October 26, 2011

- ↑ Hensleigh Wedgwood (1882). Contested etymologies in the dictionary of the Rev. W. W. Skeat. Trübner & Co. p. 14. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Chambers's encyclopaedia: a dictionary of universal knowledge for the people. W. and R. Chambers. 1868. p. 583. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "avoirdupois, n.". OED Online. Oxford University Press.(accessed March 27, 2012)

- ↑ Horace Wilmer Marsh; Annie Griswold Fordyce Marsh (1912). Constructive text-book of practical mathematics. J. Wiley & sons, inc. p. 79. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ↑ United States. National Bureau of Standards. weights and measures. Taylor & Francis. p. 22. GGKEY:4KXNZ63BNUF. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ↑ Skinner, F.G. (1952). "The English Yard and Pound Weight". Bulletin of the British Society for the History of Science. 1 (7): 186. doi:10.1017/S0950563600000646.

- ↑ Desiderius Erasmus; Alexander Dalzell; Charles Garfield Nauert (2003). The Correspondence of Erasmus Letters 1658 to 1801: January 1526-March 1527. University of Toronto Press. p. 607. ISBN 978-0-8020-4831-8. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ The statutes at large: from the ... year of the reign of ... to the ... year of the reign of .. 1763. pp. 148–9. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ Tractatus de Penderibus et Mensuris

- ↑ The statutes at large: from the ... year of the reign of ... to the ... year of the reign of .. 1763. p. 227. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- 1 2 The statutes at large: from the ... year of the reign of ... to the ... year of the reign of .. 1763. p. 264. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ A bronze Edward III standard weight of 14lb (1327-1377) Archived April 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ A bronze Edward III standard weight of 91lb ( 1⁄4 sack) (1327-1377) Archived April 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Skinner, F.G. (1952). "The English Yard and Pound Weight". Bulletin of the British Society for the History of Science. 1 (7): 185. doi:10.1017/S0950563600000646.

- ↑ A bronze Edward III standard weight of 56lb (1327-1377) Archived May 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Look up avoirdupois in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Avoirdupois". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 66.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Avoirdupois". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 66.- A bronze Edward III standard weight of 14lb (1327-1377)

- A bronze Edward III standard weight of 91lb (1/4 sack) (1327-1377)