Madeira

| Madeira | |||

| Autonomous Region (Região Autónoma) | |||

A January 2014 view of Funchal, the capital city of the autonomous region. | |||

|

|||

| Official name: Região Autónoma da Madeira | |||

| Name origin: madeira, Portuguese for wood | |||

| Motto: Das Ilhas as Mais Belas e Livres (English: Of all islands, the most beautiful and free) | |||

| Country | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous Region | |||

| Region | Atlantic Ocean | ||

| Subregion | Tore-Madeira Ridge | ||

| Position | Madeira Platform, Savage Islands submarine mount | ||

| Islands | Madeira, Porto Santo, Desertas, Selvagens | ||

| Municipalities | Calheta, Câmara de Lobos, Funchal, Machico, Ponta do Sol, Porto Moniz, Porto Santo, Ribeira Brava, Santa Cruz, Santana, São Vicente | ||

| Capital | Funchal | ||

| Largest city | Funchal | ||

| - coordinates | 32°39′4″N 16°54′35″W / 32.65111°N 16.90972°WCoordinates: 32°39′4″N 16°54′35″W / 32.65111°N 16.90972°W | ||

| Highest point | Pico Ruivo | ||

| - location | Paul da Serra, Santana, Madeira | ||

| - elevation | 1,862 m (6,109 ft) | ||

| Lowest point | Sea level | ||

| - location | Atlantic Ocean, Madeira | ||

| - elevation | 0 m (0 ft) | ||

| Area | 801 km2 (309 sq mi) | ||

| Population | 289,000 (2016) Estimate[1] | ||

| Density | 308.5/km2 (799/sq mi) | ||

| Settlement | c. 1420 | ||

| - Administrative autonomy | c. 1895 | ||

| - Political autonomy | 1 July 1976 | ||

| Discovery | c. 1415 | ||

| Management | |||

| - location | Assembleia Regional, Sé, Funchal | ||

| - elevation | 16 m (52 ft) | ||

| - coordinates | 32°38′49.96″N 16°54′29.59″W / 32.6472111°N 16.9082194°W | ||

| Government | |||

| - location | Quinta Vigia, Sé, Funchal | ||

| - elevation | 51 m (167 ft) | ||

| - coordinates | 32°38′42.39″N 16°54′57.16″W / 32.6451083°N 16.9158778°W | ||

| President (Government) | Miguel Albuquerque (PPD/PSD) | ||

| - President (Assembleia) | José Lino Tranquada Gomes (PPD/PSD) | ||

| Timezone | WET (UTC+0) | ||

| - summer (DST) | WEST (UTC+1) | ||

| ISO 3166-2 code | PT-30 | ||

| Postal code | 9XXX-XXX | ||

| Area code | (+351) 291 XXX XXX | ||

| ccTLD | .pt | ||

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy | ||

| Drive | right-side | ||

| Demonym | Madeiran; Madeirense | ||

| Patron Saint | Nossa Senhora do Monte | ||

| Holiday | 1 July | ||

| Anthem | A Portuguesa (national) Hino da Madeira (regional) | ||

| Currency | Euro (€)[2] | ||

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate | ||

| - Total | € 5.224 billion[3] | ||

| - Per capita | € 21,100[3] | ||

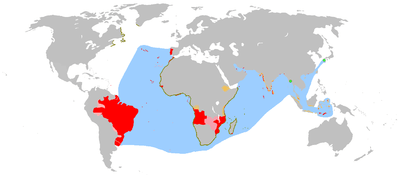

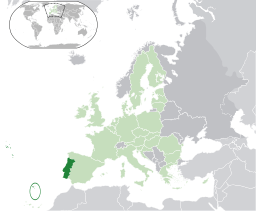

Location of Madeira relative to Portugal (green) and the rest of the European Union (light green) | |||

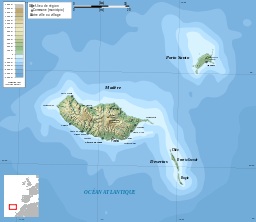

Distribution of the islands of the archipelago (not including the Savage Islands) | |||

| Wikimedia Commons: Madeira | |||

| Statistics: Instituto Nacional de Estatística[4] | |||

| Website: www.gov-madeira.pt | |||

| Geographic detail from CAOP (2010)[5] produced by Instituto Geográfico Português (IGP) | |||

Madeira (/məˈdɪərə/ mə-DEER-ə or /məˈdɛərə/ mə-DAIR-ə; Portuguese: [mɐˈðejɾɐ] or [mɐˈðɐjɾɐ]) is a Portuguese archipelago situated in the north Atlantic Ocean, southwest of Portugal. Its total population was estimated in 2011 at 267,785. The capital of Madeira is Funchal, located on the main island's south coast.

The archipelago is just under 400 kilometres (250 mi) north of Tenerife, Canary Islands. Since 1976, the archipelago has been one of the two Autonomous regions of Portugal (the other being the Azores, located to the northwest). It includes the islands of Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Desertas, administered together with the separate archipelago of the Savage Islands. It is an outermost region of the European Union.[6]

Madeira was claimed by Portuguese sailors in the service of Prince Henry the Navigator in 1419 and settled after 1420. The archipelago is considered to be the first territorial discovery of the exploratory period of the Portuguese Age of Discovery, which extended from 1415 to 1542.

Today, it is a popular year-round resort, being visited every year by about one million tourists.[7] The region is noted for its Madeira wine, gastronomy, historical and cultural value, its flora and fauna, landscapes (Laurel forest) which are classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and embroidery artisans. Its annual New Year celebrations feature the largest fireworks show in the world, as officially recognised by Guinness World Records in 2006.[8][9] The main harbour in Funchal is the leading Portuguese port in cruise liner dockings,[10] being an important stopover for commercial and trans-Atlantic passenger cruises between Europe, the Caribbean and North Africa. Madeira is the second richest region of Portugal by GDP per capita, being only surpassed by Lisbon.[11]

History

Exploration

Pliny mentioned certain "Purple Islands", their position corresponding to the location of the Fortunate Isles (or Canary Islands), that may have referred to islands of Madeira. Plutarch (Sertorius, 75 AD) referring to the military commander Quintus Sertorius (d. 72 BC), relates that after his return to Cádiz: "The islands are said to be two in number separated by a very narrow strait and lie 10,000 furlongs (2,011.68 km) from Africa. They are called the Isles of the Blessed...".

Archeological evidence suggests that the islands may have been visited by the Vikings sometime between 900-1030 AD.[12]

Legend

During the reign of King Edward III of England, lovers Robert Machim and Anna d'Arfet were said to flee from England to France in 1346. They were driven off their course by a violent storm and their ship went aground along the coast of an island, that may have been Madeira. Later this legend was the basis of the naming of the city of Machico, in memory of the young lovers.[13]

Discovery

Knowledge of some Atlantic islands, such as Madeira, existed before their formal discovery and settlement, as the islands were shown on maps as early as 1339.[14]

13.jpg)

In 1418, two captains under service to Prince Henry the Navigator, João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira, were driven off-course by a storm to an island which they named Porto Santo (English: holy harbour) in gratitude for divine deliverance from a shipwreck. The following year, an organised expedition, under the captaincy of Zarco, Vaz Teixeira, and Bartolomeu Perestrello, traveled to the island to claim it on behalf of the Portuguese Crown. Subsequently, the new settlers observed "a heavy black cloud suspended to the southwest."[15] Their investigation revealed it to be the larger island they called Madeira.[16]

Settlement

The first Portuguese settlers began colonizing the islands around 1420 or 1425.[17]

Grain production began to fall and the ensuing crisis forced Henry the Navigator to order other commercial crops to be planted so that the islands could be profitable. The planting of sugarcane, and later Sicilian sugar beet, allowed the introduction of the "sweet salt" (as sugar was known) into Europe, where it was a rare and popular spice. These specialised plants, and their associated industrial technology, created one of the major revolutions on the islands and fuelled Portuguese industry. The expansion of sugar plantations in Madeira began in 1455 , using advisers from Sicily and financed by Genoese capital. (Genoa acted as an integral part of the island economy until the 17th century). The accessibility of Madeira attracted Genoese and Flemish traders, who were keen to bypass Venetian monopolies.

"By 1480 Antwerp had some seventy ships engaged in the Madeira sugar trade, with the refining and distribution concentrated in Antwerp. By the 1490s Madeira had overtaken Cyprus as a producer of sugar".[18]

Sugarcane production was the primary engine of the island's economy, increasing the demand for labour. African slaves were used during portions of the island's history to cultivate sugar cane, and the proportion of imported slaves reached 10% of the total population of Madeira by the 16th century.[19]

Barbary corsairs from North Africa, who enslaved Europeans from ships and coastal communities throughout the Mediterranean region, captured 1,200 people in Porto Santo in 1617.[20][21] After the 17th century, as Portuguese sugar production was shifted to Brazil, São Tomé and Príncipe and elsewhere, Madeira's most important commodity product became its wine.

The British first amicably occupied the island in 1801 whereafter Colonel William Henry Clinton became governor.[22] A detachment of the 85th Regiment of Foot under Lieutenant-colonel James Willoughby Gordon garrisoned the island.[23] After the Peace of Amiens, British troops withdrew in 1802, only to reoccupy Madeira in 1807 until the end of the Peninsular War in 1814.[24]

After the death of King John VI of Portugal, his usurper son Miguel of Portugal seized power from the rightful heir, his niece Maria II, and proclaimed himself 'Absolute King.' Madeira held out for the queen under the governor José Travassos Valdez.

World War I

On 31 December 1916 during the Great War, the German U-boat, SM U-38, captained by Max Valentiner, entered Funchal harbour on Madeira; it torpedoed and sank three ships: CS Dacia (1,856 tons),[25] SS Kanguroo (2,493 tons)[26] and Surprise (680 tons), bringing the war to Portugal by extension.[27] The commander of the French gunboat Surprise and 34 of her crew (including 7 Portuguese) died in the attack. The Dacia, a British cable-laying vessel,[28] had previously undertaken war work off the coast of Casablanca and Dakar. It was in the process of diverting the German South American cable into Brest, France. Following the attack on the ships, the Germans proceeded to bombard Funchal for two hours from a range of about 2 miles (3 km). Batteries on Madeira returned fire and eventually forced the Germans to withdraw.[29]

On 12 December 1917, 2 German U-boats, SM U-156 and SM U-157 (captained by Max Valentiner) again bombarded Funchal. This time the attack lasted around 30 minutes. Forty, 4.7-and-5.9-inch (120 and 150 mm) shells were fired. There were 3 fatalities and 17 wounded; a number of houses and Santa Clara church were hit.

Charles I (Karl I), the last Emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, went into exile in Madeira, after his second unsuccessful coup d'état in Hungary. He died there on 1 April 1922 and is buried in Monte. Charles had tried secretly in 1917 to enter into peace negotiations with France. Although his foreign minister, Count Ottokar Czernin, was interested only in negotiating a general peace to include Germany, Charles independently pursued a separate peace. He negotiated with the French using his brother-in-law, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, an officer in the Belgian Army, as intermediary. When news of the overture leaked in April 1918, Charles denied involvement until the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau published letters signed by him. Czernin resigned and Austria-Hungary became more dependent in relation to its seemingly wronged German ally. Determined to prevent an attempt to restore Charles to the throne, the Council of Allied Powers agreed he could go into exile on Madeira because it was isolated in the Atlantic and easily guarded.[30]

Autonomy and recent history

On 1 July 1976, following the democratic revolution of 1974, Portugal granted political autonomy to Madeira, celebrated on Madeira Day. The region now has its own government and legislative assembly.

In October 2012, it was reported that there was a dengue fever epidemic on the island.[31][32] There was a total of 2,168 cases reported of dengue fever since the start in October 2012. The number of cases was on the decline since mid November 2012 and by 4 February 2013, no new cases had been reported.[33]

Beginning on Monday, 8 August 2016, and continuing through at least Thursday 11 August 2016, wildfires spread on Madeira and reached Funchal, killing three and destroying 150 homes.[34]

Geography

| Madeira | |

| Island (Ilha) | |

A three-dimensional rendering of topographic maps characterizing the island of Madeira | |

| Official name: Ilha da Madeira | |

| Name origin: madeira, Portuguese for the wood | |

| Motto: Das ilhas, as mais belas e livres (Of all islands, the most beautiful and free) | |

| Nickname: Pérola do Atlântico (Pearl of the Atlantic) | |

| Country | Portugal |

|---|---|

| Autonomous Region | Madeira |

| Location | Tore-Madeira Ridge, African Tectonic Plate, Atlantic Ocean |

| Municipalities | Calheta, Câmara de Lobos, Funchal, Machico, Ponta do Sol, Porto Moniz, Ribeira Brava, Santa Cruz, Santana, São Vicente |

| Highest point | Pico Ruivo |

| - location | Pico Ruivo, [(Santana)], Santana |

| - elevation | 1,862 m (6,109 ft) |

| Lowest point | Sea level |

| - location | Atlantic Ocean |

| - elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 57 km (35 mi), West-East |

| Width | 22 km (14 mi), North-South |

| Area | 740.7 km2 (286 sq mi) |

| Biomes | Temperate, Mediterranean |

| Geology | Alkali basalt, Tephra, Trachyte, Trachybasalt |

| Orogeny | Volcanism |

| Period | Miocene |

| Demonym | Madeirense; Madeiran |

| Ethnic groups | Portuguese |

| Wikimedia Commons: Madeira | |

| Website: www.gov-madeira.pt | |

| Statistics from INE (2001); geographic detail from Instituto Geográfico Português (2010) | |

The archipelago of Madeira is located 520 km (280 nmi) from the African coast and 1,000 km (540 nmi) from the European continent (approximately a one-and-a-half hour flight from the Portuguese capital of Lisbon).[35] It is found in the extreme south of the Tore-Madeira Ridge, a bathymetric structure of great dimensions oriented along a north-northeast to south-southwest axis that extends for 1,000 kilometres (540 nmi). This submarine structure consists of long geomorphological relief that extends from the abyssal plain to 3500 metres; its highest submersed point is at a depth of about 150 metres (around latitude 36ºN). The origins of the Tore-Madeira Ridge are not clearly established, but may have resulted from a morphological buckling of the lithosphere.[36][37]

Islands and islets

Madeira (740.7 km2), including Ilhéu de Agostinho, Ilhéu de São Lourenço, Ilhéu Mole (northwest);

Porto Santo (42.5 km2), including Ilhéu de Baixo ou da Cal, Ilhéu de Ferro, Ilhéu das Cenouras, Ilhéu de Fora, Ilhéu de Cima;

Desertas Islands (14.2 km2), including the three uninhabited islands: Deserta Grande Island, Bugio Island and Ilhéu de Chão;

Savage Islands (3.6 km2), archipelago 280 km south-southeast of Madeira Island including three main islands and 16 uninhabited islets in two groups: the Northwest Group (Selvagem Grande Island, Ilhéu de Palheiro da Terra, Ilhéu de Palheiro do Mar) and the Southeast Group (Selvagem Pequena Island, Ilhéu Grande, Ilhéu Sul, Ilhéu Pequeno, Ilhéu Fora, Ilhéu Alto, Ilhéu Comprido, Ilhéu Redondo, Ilhéu Norte).

Madeira Island

The island of Madeira is at the top of a massive shield volcano that rises about 6 km (20,000 ft) from the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, on the Tore underwater mountain range. The volcano formed atop an east-west rift[38][39] in the oceanic crust along the African Plate, beginning during the Miocene epoch over 5 million years ago, continuing into the Pleistocene until about 700,000 years ago.[40] This was followed by extensive erosion, producing two large amphitheatres open to south in the central part of the island. Volcanic activity later resumed, producing scoria cones and lava flows atop the older eroded shield. The most recent volcanic eruptions were on the west-central part of the island only 6,500 years ago, creating more cinder cones and lava flows.[40]

It is the largest island of the group with an area of 741 km2 (286 sq mi), a length of 57 km (35 mi) (from Ponte de São Lourenço to Ponte do Pargo), while approximately 22 km (14 mi) at its widest point (from Ponte da Cruz to Ponte São Jorge), with a coastline of 150 km (90 mi). It has a mountain ridge that extends along the centre of the island, reaching 1,862 meters (6,109 feet) at its highest point (Pico Ruivo), while much lower (below 200 meters) along its eastern extent. The primitive volcanic foci responsible for the central mountainous area, consisted of the peaks: Ruivo (1862 meters), Torres (1851 meters), Arieiro (1818 meters), Cidrão (1802 meters), Cedro (1759 meters), Casado (1725 meters), Grande (1657 meters), Ferreiro (1582 meters). At the end of this eruptive phase, an island circled by reefs was formed, its marine vestiges are evident in a calcareous layer in the area of Lameiros, in São Vicente (which was later explored for calcium oxide production). Sea cliffs, such as Cabo Girão, valleys and ravines extend from this central spine, making the interior generally inaccessible.[41] Daily life is concentrated in the many villages at the mouths of the ravines, through which the heavy rains of autumn and winter usually travel to the sea.[42]

Climate

Madeira has been classified as a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa/Csb).[43] Based on differences in sun exposure, humidity, and annual mean temperature, there are clear variations between north- and south-facing regions, as well as between some islands. The islands are strongly influenced by the Gulf Stream and Canary Current, giving mild year-round temperatures; according to the Instituto de Meteorologia (IM), the average annual temperature at Funchal weather station is 19.6 °C (67.3 °F) for the 1980–2010 period. For the 1960–1990 period, IM published an article showing that some regions in the South Coastline surpass 20 °C (68 °F) in annual average. Other microclimates are expected to exist, from the constantly humid wettest points of the mountains to the desert and arid Selvagens islands. Porto Santo has at least one weather station with a semiarid climate (BSh). On the highest windward slopes of Madeira, rainfall exceeds 50 inches (1250 mm) per year, mostly falling between October and April. In most winters snowfall occurs in the mountains of Madeira.

- View from Pico do Arieiro

Lava pools[44] in Porto Moniz

Lava pools[44] in Porto Moniz Porto Santo's lack of higher mountains results in a paradoxical landscape when comparing it with its sister island Madeira

Porto Santo's lack of higher mountains results in a paradoxical landscape when comparing it with its sister island Madeira The Desertas Islands in the distance at sunrise

The Desertas Islands in the distance at sunrise.jpg) Cloud river formation between Madeiran mountains

Cloud river formation between Madeiran mountains In some winters snow can occasionally be seen from Funchal, while the temperatures in the city stay mild

In some winters snow can occasionally be seen from Funchal, while the temperatures in the city stay mild

| Climate data for Funchal, capital of Madeira | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.5 (77.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

32.6 (90.7) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.7 (94.5) |

37.7 (99.9) |

38.5 (101.3) |

38.4 (101.1) |

34.1 (93.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.7 (67.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

20.7 (69.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.7 (62.1) |

16.6 (61.9) |

17.2 (63) |

17.5 (63.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.2 (72) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.9 (57) |

14.4 (57.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.7 (63.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

20.0 (68) |

20.0 (68) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

15.0 (59) |

16.5 (61.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.4 (43.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 74.1 (2.917) |

83.0 (3.268) |

60.2 (2.37) |

44.0 (1.732) |

28.9 (1.138) |

7.2 (0.283) |

1.6 (0.063) |

2.0 (0.079) |

32.9 (1.295) |

89.5 (3.524) |

88.8 (3.496) |

115.0 (4.528) |

627.2 (24.693) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 12 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 87 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 167.4 | 171.1 | 204.6 | 225.0 | 213.9 | 198.0 | 244.9 | 260.4 | 225.0 | 204.6 | 168.0 | 164.3 | 2,447.2 |

| Source: Instituto de Meteorologia,[45] ClimaTemps.com[46] for Sunshine hours data | |||||||||||||

Wildfires

Drought conditions, coupled with hot and windy weather in summer, have caused numerous wildfires in recent years. The largest of the fires in August 2010 burned through 95 percent of the Funchal Ecological Park, a 1,000-hectare preserve set aside to restore native vegetation to the island.[47][48] In July 2012 Madeira was suffering again from severe drought. Wildfires broke out on July 18, in the midst of temperatures up to 40 degrees Celsius (more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit) and high winds. By July 20, fires had spread to the nearby island of Porto Santo, and firefighters were sent from mainland Portugal to contain the multiple blazes.[49][50][51][52] Numerous residents had to be evacuated and firefighters were sent from the mainland to help battle the fires.

In August 2013, a hospital and some private homes were evacuated as a wildfire approached Funchal. A number of homes were destroyed when the fire hit Monte, a suburb of Funchal.[53][54]

Biome

The Macaronesia region harbours an important floral diversity. In fact, the archipelago's forest composition and maturity are quite similar to the forests found in the Tertiary period that covered Southern Europe and Northern Africa millions of years ago. The great biodiversity of Madeira is phytogeographically linked to the Mediterranean region, Africa, America and Australia, and interest in this phytogeography has been increasing in recent years due to the discovery of some epiphytic bryophyte species with non-adjacent distribution.

Madeira also has many endemic species of fauna – mostly invertebrates which include the extremely rare Madeiran large white butterfly but also some vertebrates such as the native bat, some lizards species, and some birds as already mentioned. The biggest tarantula of Europe is found on Desertas islands of Madeira and can be as wide as a man's hand. These islands have more than 250 species of land molluscs (snails and slugs), some with very unusual shell shape and colours, most of which are endemic and vulnerable.

Madeira has three endemic bird species: Zino's petrel, the Trocaz pigeon and the Madeira firecrest, while the Madeiran chaffinch is an endemic subspecies. It is also important for breeding seabirds, including the Madeiran storm-petrel, Barolo shearwater and Cory's shearwater.

Native birds gallery

In the south, there is very little left of the indigenous subtropical rainforest which once covered the whole island (the original settlers set fire to the island to clear the land for farming) and gave it the name it now bears (Madeira means "wood" in Portuguese). However, in the north, the valleys contain native trees of fine growth. These "laurisilva" forests, called lauraceas madeirense, notably the forests on the northern slopes of Madeira Island, are designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The critically endangered vine Jasminum azoricum is one of the plant species that is endemic to Madeira.[55]

Native flora gallery

Levadas

The island of Madeira is wet in the northwest but dry in the southeast. In the 16th century the Portuguese started building levadas or aqueducts to carry water to the agricultural regions in the south. The most recent were built in the 1940s. Madeira is very mountainous, and building the levadas was difficult and often sentenced criminals or slaves were used. Many are cut into the sides of mountains, and it was also necessary to dig 25 miles (40 km) of tunnels, some of which are still accessible.

Today the levadas not only supply water to the southern parts of the island but provide hydro-electric power. There are over 1,350 miles (2,170 km) of levadas and they provide a network of walking paths. Some provide easy and relaxing walks through the countryside, but others are narrow, crumbling ledges where a slip could result in serious injury or death.

Two of the most popular levadas to hike are the Levada do Caldeirão Verde and the Levada do Caldeirão do Inferno which should not be attempted by hikers prone to vertigo or without torches and helmets. The Levada do Caniçal is a much easier walk, running 7.1 miles (11.4 km) from Maroços to the Caniçal Tunnel. It is known as the mimosa levada because mimosa trees are found all along the route.

Governance

Administratively, Madeira (with a population of 267,302 inhabitants in 2011[56]) and covering an area of 768.0 km2 (296.5 sq mi) is organised into eleven municipalities:[57]

| Municipality | Population (2011)[56] | Area | Main settlement | Parishes |

| Funchal[58] | 111,892 | 75.7 km2 (29.2 sq mi) | Funchal | 10 |

| Santa Cruz[59] | 43,005 | 68.0 km2 (26.3 sq mi) | Santa Cruz | 5 |

| Câmara de Lobos | 35,666 | 52.6 km2 (20.3 sq mi) | Câmara de Lobos | 5 |

| Machico | 21,828 | 67.6 km2 (26.1 sq mi) | Machico | 5 |

| Ribeira Brava | 13,375 | 64.9 km2 (25.1 sq mi) | Ribeira Brava | 4 |

| Calheta | 11,521 | 110.3 km2 (42.6 sq mi) | Calheta | 8 |

| Ponta do Sol | 8,862 | 46.8 km2 (18.1 sq mi) | Ponta do Sol | 3 |

| Santana | 7,719 | 93.1 km2 (35.9 sq mi) | Santana | 6 |

| São Vicente | 5,723 | 80.8 km2 (31.2 sq mi) | São Vicente | 3 |

| Porto Santo[60] | 5,483 | 42.4 km2 (16.4 sq mi) | Vila Baleira | 1 |

| Porto Moniz | 2,711 | 82.6 km2 (31.9 sq mi) | Porto Moniz | 4 |

Funchal

Funchal is the capital and principal city of the Madeira Autonomous Region, located along the southern coast of the island of Madeira. It is a modern city, located within a natural geological "amphitheatre" composed of vulcanological structure and fluvial hydrological forces. Beginning at the harbour (Porto de Funchal), the neighbourhoods and streets rise almost 1,200 metres (3,900 ft), along gentle slopes that helped to provide a natural shelter to the early settlers.

Population

Demographics

When the Portuguese discovered the island of Madeira in 1419, it was uninhabited by humans, with no aboriginal population. The island was settled by Portuguese people, especially farmers from the Minho region,[61] meaning that Madeirans (Portuguese: Madeirenses), as they are called, are ethnically Portuguese, though they have developed their own distinct regional identity and cultural traits.

The region has a total population of just under 270,000, the majority of whom live on the main island of Madeira where the population density is 337/km2; meanwhile only around 5,000 live on the Porto Santo Island where the population density is 112/km2.

Diaspora

Madeirans migrated to the United States, Venezuela, Brazil, British Guiana, St. Vincent and Trinidad.[62][63] Madeiran immigrants in North America mostly clustered in the New England and mid-Atlantic states, Toronto, Northern California, and Hawaii. The city of New Bedford is especially rich in Madeirans, hosting the Museum of Madeira Heritage, as well as the annual Madeiran and Luso-American celebration, the Feast of the Blessed Sacrament, the world's largest celebration of Madeiran heritage, regularly drawing crowds of tens of thousands to the city's Madeira Field.

In 1846, when a famine struck Madeira over 6,000 of the inhabitants migrated to British Guiana. In 1891 they numbered 4.3% of the population.[64] In 1902 in Honolulu, Hawaii there were 5,000 Portuguese people, mostly Madeirans. In 1910 this grew to 21,000.

1849 saw an emigration of Protestant religious exiles from Madeira to the United States, by way of Trinidad and other locations in the West Indies. Most of them settled in Illinois[65] with financial and physical aid of the American Protestant Society, headquartered in New York City. In the late 1830s the Reverend Robert Reid Kalley, from Scotland, a Presbyterian minister as well as a physician, made a stop at Funchal, Madeira on his way to a mission in China, with his wife, so that she could recover from an illness. The Rev. Kalley and his wife stayed on Madeira where he began preaching the Protestant gospel and converting islanders from Catholicism.[66] Eventually, the Rev. Kalley was arrested for his religious conversion activities and imprisoned. Another missionary from Scotland, William Hepburn Hewitson, took on Protestant ministerial activities in Madeira. By 1846, about 1,000 Protestant Madeirenses, who were discriminated against and the subjects of mob violence because of their religious conversions, chose to immigrate to Trinidad and other locations in the West Indies in answer for a call for sugar plantation workers.[67] The Madeirenses exiles did not fare well in the West Indies. The tropical climate was unfamiliar and they found themselves in serious economic difficulties. By 1848, the American Protestant Society raised money and sent the Rev. Manuel J. Gonsalves, a Baptist minister and a naturalized U.S. citizen from Madeira, to work with the Rev. Arsenio da Silva, who had emigrated with the exiles from Madeira, to arrange to resettle those who wanted to come to the United States. The Rev. da Silva died in early 1849. Later in 1849, the Rev. Gonsalves was then charged with escorting the exiles from Trinidad to be settled in Sangamon and Morgan counties in Illinois on land purchased with funds raised by the American Protestant Society. Accounts state that anywhere from 700 to 1,000 exiles came to the United States at this time.[68][69]

There are several large Madeiran communities around the world, such as the great number in the UK, including Jersey,[70] the Portuguese British community mostly made up of Madeirans celebrate Madeira Day.

Economy

The setting-up of a free trade zone has led to the installation, under more favourable conditions, of infrastructure, production shops and essential services for small and medium-sized industrial enterprises. The Madeira Free Trade Zone,[71] also called the Madeira International Business Centre, being a tax-privileged economic area, provides an incentive for companies, offering them financial and tax advantages via a whole range of activities exercised in the Industrial Free Zone, the Off-Shore Financial Centre, the International Shipping Register organisation, and the International Service Centre.

Madeira has been a significant recipient of European Union aid, totalling up to €2 billion. In 2012, it was reported that despite a population of just 250,000, the local administration owes some €6 billion.[72]

Tourism

.jpg)

Tourism is an important sector in the region's economy since it contributes 20%[73] to the region's GDP, providing support throughout the year for commercial, transport and other activities and constituting a significant market for local products. The share in Gross Value Added of hotels and restaurants (9%) also highlights this phenomenon. The island of Porto Santo, with its 9 km (5.6 mi) long beach and its climate, is entirely devoted to tourism.

Visitors are mainly from the European Union, with German, British, Scandinavian and Portuguese tourists providing the main contingents. The average annual occupancy rate was 60.3% in 2008,[74] reaching its maximum in March and April, when it exceeds 70%.

Whale watching

Whale watching has become very popular in recent years. Many species of dolphins such as common dolphin, spotted dolphin, striped dolphin, bottlenose dolphin, short-finned pilot whale, and whales such as Bryde's whale, Sei whale,[75] fin whale, sperm whale, beaked whales can be spotted near the coast or offshore.[76]

Immigration

Madeira is part of the Schengen Area.

There were in 2009, 7,105 legal immigrants living in Madeira Islands. They come mostly from Brazil (1,300), the United Kingdom (912), Venezuela (732) and Ukraine (682), according to SEF.[77] But in 2013, that number dropped to 5,829, also according to SEF.[77]

Transport

The Islands have two airports, Madeira Airport (Cristiano Ronaldo Airport) and Porto Santo Airport, on the islands of Madeira and Porto Santo respectively. From Madeira Airport the most frequent flights are to Lisbon. There are also direct flights to over 30 other airports in Europe and nearby islands.[78]

Transport between the two main islands is by plane, or ferries from the Porto Santo Line,[79] the latter also carrying vehicles. Visiting the interior of the islands is now easy thanks to construction of the Vias Rápidas, major roads built during Portugal's economic boom. Modern roads reach all points of interest on the islands.

Funchal has an extensive public transportation system. Bus companies, including Horários do Funchal which has been operating for over a hundred years, have regularly scheduled routes to all points of interest on the island.

Culture

Music

Folklore music in Madeira is widespread and mainly uses local musical instruments such as the machete, rajao, brinquinho and cavaquinho, which are used in traditional folkloric dances like the bailinho da Madeira.

Emigrants from Madeira also influenced the creation of new musical instruments. In the 1880s, the ukulele was created, based on two small guitar-like instruments of Madeiran origin, the cavaquinho and the rajao. The ukulele was introduced to the Hawaiian Islands by Portuguese immigrants from Madeira and Cape Verde.[80] Three immigrants in particular, Madeiran cabinet makers Manuel Nunes, José do Espírito Santo, and Augusto Dias, are generally credited as the first ukulele makers.[81] Two weeks after they disembarked from the SS Ravenscrag in late August 1879, the Hawaiian Gazette reported that "Madeira Islanders recently arrived here, have been delighting the people with nightly street concerts."[82]

Cuisine

Because of the geographic situation of Madeira in the Atlantic Ocean, the island has an abundance of fish of various kinds. The species that are consumed the most are espada (black scabbardfish), blue fin tuna, white marlin, blue marlin, albacore, bigeye tuna, wahoo, spearfish, skipjack tuna and many others are found in the local dishes as they are found up and down the coast of Madeira. Espada is often served with banana. Bacalhau is also popular just like in Portugal.

There are many meat dishes on Madeira, one of the most popular being espetada.[83] Espetada is traditionally made of large chunks of beef rubbed in garlic, salt and bay leaf and marinated for 4 to 6 hours in Madeira wine, red wine vinegar and olive oil then skewered onto a bay laurel stick and left to grill over smouldering wood chips. These are so integral a part of traditional eating habits that a special iron stand is available with a T-shaped end, each branch of the "T" having a slot in the middle to hold a brochette (espeto in Portuguese); a small plate is then placed underneath to collect the juices. The brochettes are very long and have a V-shaped blade in order to pierce the meat more easily. It is usually accompanied with the local bread called bolo do caco.

Other popular dishes in Madeira include açorda, feijoada, carne de vinha d'alhos.

Traditional pastries in Madeira usually contain local ingredients, one of the most common being mel de cana, literally "sugarcane honey" (molasses). The traditional cake of Madeira is called Bolo de Mel, which translates as (Sugarcane) "Honey Cake" and according to custom, is never cut with a knife, but broken into pieces by hand. It is a rich and heavy cake. The cake commonly well known as "Madeira Cake" in England also finds its naming roots in the Island of Madeira.

Malasadas are a Madeiran creation which were taken around the world by emigrants to places such as Hawaii. In Madeira, Malasadas are mainly consumed during the Carnival of Madeira. Pastéis de nata, as in the rest of Portugal, are also very popular.

Milho frito is a very popular dish in Madeira which is very similar to the Italian dish polenta. Açorda Madeirense is another popular local dish.

Beverages

Madeira is a fortified wine, produced in the Madeira Islands; varieties may be sweet or dry. It has a history dating back to the Age of Exploration when Madeira was a standard port of call for ships heading to the New World or East Indies. To prevent the wine from spoiling, neutral grape spirits were added. However, wine producers of Madeira discovered, when an unsold shipment of wine returned to the islands after a round trip, that the flavour of the wine had been transformed by exposure to heat and movement. Today, Madeira is noted for its unique winemaking process which involves heating the wine and deliberately exposing the wine to some levels of oxidation.[84] Most countries limit the use of the term Madeira to those wines that come from the Madeira Islands, to which the European Union grants Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status.[85]

A local beer called Coral is produced by the Madeira Brewery, which dates from 1872. Other alcoholic drinks are also popular in Madeira, such as the locally created Poncha, Niquita, Pé de Cabra, Aniz, as well as Portuguese drinks such as Macieira Brandy, Licor Beirão.

Laranjada is a type of carbonated soft drink with an orange flavour, its name being derived from the Portuguese word laranja ("orange"). Launched in 1872 it was the first soft drink to be produced in Portugal, and remains very popular to the present day. Brisa drinks, a brand name, are also very popular and come in a range of flavours.

There is also a huge coffee culture in Madeira. Like in mainland Portugal, popular coffee-based drinks include Garoto, Galão, Bica, Café com Cheirinho, Mazagran, Chinesa and many more.

Sports

Sister provinces

Madeira Island has the following sister provinces:

-

: Autonomous Region of Aosta Valley, Italy (1987)

: Autonomous Region of Aosta Valley, Italy (1987) -

: Bailiwick of Jersey, British Crown Dependencies (1998)

: Bailiwick of Jersey, British Crown Dependencies (1998) -

: Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

: Eastern Cape Province, South Africa -

: Jeju Province, South Korea (2007)

: Jeju Province, South Korea (2007) -

: Gibraltar, British Overseas Territory

: Gibraltar, British Overseas Territory

Postage stamps

Portugal has issued postage stamps for Madeira during several periods, beginning in 1868.

Notable citizens

The following people were either born or have lived part of their lives in Madeira:

- Joe Berardo, Portuguese millionaire, and art collector

- Rubina Berardo, Portuguese politician

- António de Abreu, naval officer and navigator

- Nadia Almada, a winner of the British reality show Big Brother

- Menasseh Ben Israel, Jewish Rabbi.

- Charles I of Austria, deposed monarch, died in exile on Madeira in 1922

- Catarina Fagundes, Olympic athlete for windsurf

- Vânia Fernandes, Portuguese singer who represented Portugal in Eurovision 2008

- José Vicente de Freitas, military and politician

- Vasco da Gama Rodrigues, poet, born in Paul do Mar

- Teodósio Clemente de Gouveia, Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church

- George Walter Grabham, geologist

- Herberto Hélder, poet

- Moisés Henriques, former Australian Under-19 Captain and current NSW Blues cricketer

- Alberto João Jardim, second President of the Regional Government

- Luís Jardim, producer of music

- Paul Langerhans, German pathologist and biologist

- Fátima Lopes, fashion designer

- Jaime Ornelas Camacho, first and former President of the Regional Government

- Aires de Ornelas e Vasconcelos, former Archbishop of the former Portuguese colonial enclave Goa (in India)

- Sir Lloyd William Matthews, British naval officer, politician and abolitionist

- Dionísio Pestana, president of the Pestana Group

- Rigo 23, artist

- João Rodrigues, Olympic windsurfer

- Cristiano Ronaldo, Real Madrid, Portugal and former Manchester United football player

- John Santos, photographer

- Ana da Silva, founding member of the post-punk band The Raincoats

- Pedro Macedo Camacho, Composer of Requiem to Inês de Castro and Star Citizen, starring Gary Oldman, Mark Hamill and Gillian Anderson

- Manoel Dias Soeyro or Menasseh Ben Israel (1604–1657), Sephardi Rabbi and publisher

- Artur de Sousa Pinga, former CS Marítimo and FC Porto football player

- Maximiano de Sousa (Max), popular singer, born in Funchal

- Virgílio Teixeira, actor

- José Travassos Valdez, 1st Count of Bonfim, governor in 1827–1828

- Miguel Albuquerque, third and current President of the Regional Government

- Bernardo Sousa, rally driver in the WRC

See also

- "Have Some Madeira M'Dear"

- List of birds of Madeira

- Madeira Airport

- Madeira Islands Open, an annual European Tour golf tournament

- Surfing in Madeira

References

Notes

- ↑ http://www.ine.pt/scripts/flex_v10/Main.html

- ↑ Until 2002, the Portuguese escudo was used in financial transactions, and until 1910 the Portuguese real was the currency used by the monarchy of Portugal.

- 1 2 "Regiões de Portugal". AICEP.

- ↑ INE, ed. (2010), Censos 2011 - Resultadas Preliminares [2011 Census - Preliminary Results] (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: Instituto Nacional de Estatística, retrieved 1 July 2011

- ↑ IGP, ed. (2010), Carta Administrativa Oficial de Portugal (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: Instituto Geográfico Português, retrieved 1 July 2011

- ↑ "EUROPA - Glossary - Outermost regions". Europa.eu. 17 July 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ "Hotelaria da Madeira suaviza quebras em 2010 apesar de impacto devastador dos temporais". presstur.com. October 2, 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ Archived 23 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "A Guinness World Record Fireworks Show – Madeira Island, 2006-2007 New Year Eve at Wayfaring Travel Guide". Wayfaring.info. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ "Madeira welcomes most cruisers". The Portugal News. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "New Eurostat website - Eurostat". Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ World Archaeology, Issue 66, August/September 2014, Volume 6, No. 6, page 64.

- ↑ Nicholas Cayetano de Bettencourt Pitta, 1812, p.11-17

- ↑ Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2004). "Machim (supp. fl. 14th cent.)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17535. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ↑ Nicholas Cayetano de Bettencourt Pitta, 1812, p.20

- ↑ The discoveries of Porto Santo and Madeira were first described by Gomes Eanes de Zurara in Chronica da Descoberta e Conquista da Guiné. (Eng. version by Edgar Prestage in 2 vols. issued by the Hakluyt Society, London, 1896–1899: The Chronicle of Discovery and Conquest of Guinea.) French author Arkan Simaan refers to these discoveries in his historical novel based on Azurara's Chronicle: L'Écuyer d'Henri le Navigateur (2007), published by Éditions l'Harmattan, Paris.

- ↑ Dervenn, Claude (1957). Madeira. Translated by Hogarth-Gaute, Frances. London, UK: George G. Harrap and Co. p. 20. OCLC 645870163. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

And when he returned in May 1420 to take possession of "his" island, it was with his wife and the sons and daughters that the virtuous Constanga had given him.

- ↑ Ponting, Clive (2000) [2000]. World history: a new perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 482. ISBN 0-7011-6834-X.

- ↑ Godinho, V. M. Os Descobrimentos e a Economia Mundial, Arcádia, 1965, Vol 1 and 2, Lisboa

- ↑ Fernando Augusto da Silva & Carlos Azevedo de Menezes, "Porto Santo", Elucidário Madeirense, vol. 3 (O-Z), Funchal, DRAC, p. 124.

- ↑ Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800. Robert Davis (2004). p.7. ISBN 1-4039-4551-9.

- ↑ "Officer's presentation sword given to Brigadier General William Henry Clinton from the British Consul and Factory in Madeira, 1802". National Army Museum. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ↑ "GORDON, Sir James Willoughby, 1st bt. (1772-1851), of Niton, I.o.W". UK Parliament. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ↑ "The Map Room: Africa: Madeira". British Empire. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ "Cable ship Dacia". Ships hit by U-boats - German and Austrian U-boats of World War One - Kaiserliche Marine. uboat.net. 13 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ↑ "Submarine carrier Kanguroo". Ships hit by U-boats - German and Austrian U-boats of World War One - Kaiserliche Marine. uboat.net. 13 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ↑ "Gunboat Surprise". Ships hit by U-boats - German and Austrian U-boats of World War One - Kaiserliche Marine. uboat.net. 13 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ↑ Glover, Bill (10 July 2015). "CS Dacia". History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ "A bit of History". Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- ↑ The New York Times, 6 November 1921 (accessed 4 May 2009)

- ↑ "Denguekuume leviää Madeiralla ('Dengue Fever Spreads In Madeira')". YLE.fi. 10 October 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ "Dengue Fever in Madeira, Portugal". WHO. 17 October 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ "Dengue outbreak in Madeira controlled". Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ↑ Minder, Raphael (August 11, 2016). "Deadly Wildfires on Portuguese Island of Madeira Reach Its Largest City". nytimes.com. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Madeira Islands Tourism". Madeiraislands.travel. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ Ribeiro et al., 1996

- ↑ Kullberg & Kullberg, 2000

- ↑ Geldemacher et al., 2000

- ↑ Ribeiro, 2001

- 1 2 "Madeira". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ "MadeiraHelp.com". MadeiraHelp.com. 22 February 1999. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ Robert White, 1851, p.4

- ↑ "World Map of Köppen−Geiger Climate Classification".

- ↑ "Lava Pools". tripadvisor.com.

- ↑ "Weather Information for Funchal".

- ↑ "Funchal, Madeira Climate, Temperature, Average Weather History, Rainfall/Precipitation, Sunshine".

- ↑ Riebeek, Holli. "Fires in Madeira, Portugal". Earth Observatory. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ↑ Sapa-DPA (16 August 2010). "Wildfires ravage Portuguese nature parks". IOL News. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

Fires that had raged there in the recent days had devastated 95 percent of Funchal Ecological Park, destroying a decade of efforts to replant indigenous species in the area measuring 1 000 hectares, the daily Publico quoted environmentalists as saying.

- ↑ "Fires ravage Madeira islands and mainland Portugal". Reuters. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

.

- ↑ Scott, Michon. "Madeira Wildfires". Earth Observatory. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ↑ Miller, Shari (20 July 2012). "Holiday resorts under threat as towering walls of flame ravage Madeira islands". Daily Mail. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

Dds.

- ↑ "Portugal's Madeira hit by forest fires". BBC News. 20 July 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

ces.

- ↑ Porter, Tom (17 August 2013). "Hospital Evacuated as Fire Rages on Madeira". IBTimes UK. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

.

- ↑ "Wildfire inferno forces hospital and homes to be evacuated on Portuguese island Madeira". euronews. 17 August 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

.

- ↑ Fernandes, F. (2011). "Jasminum azoricum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Censos 2011 Resultados Preliminares 2011". INE.

- ↑ Map of municipalities at FreguesiasDePortugas l.com

- ↑ Statistics include Savage Islands, which are administered by the parish of Sé

- ↑ Statistics include the mainland parish of Santa Cruz and the islands of the Desertas

- ↑ Statistics represent island population; Porto Santo is the second largest island in the archipelago of Madeira

- ↑ "Alberto Vieira, ''O Infante e a Madeira: dúvidas e certezas, Centro Estudos História Atlântico". Ceha-madeira.net. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ "Madeiran Portuguese Migration to Guyana, St. Vincent, Antigua and Trinidad: A Comparative Overview" (PDF). Jo-Anne S. Ferreira, University of the West Indies, St. Augustine

- ↑ "Madeira and Emigration"

- ↑ "Portuguese emigration from Madeira to British Guiana"

- ↑ "Protestant Exiles from Madeira in Illinois". loc.gov.

- ↑ "Portuguese Immigration To Jacksonville In 1849". orgsites.com.

- ↑ "History of Sangamon County, Illinois". google.com.

- ↑ "Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois". google.com.

- ↑ "The Christian World". google.com.

- ↑ "BBC – Jersey Voices"

- ↑ "International Business Centre of Madeira - About IBC". ibc-madeira.com.

- ↑ "Billions of euros of EU money yet Madeira has built up massive debts". Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ "Telegraph article". www.telegraph.co.uk. 23 February 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ "Statistics from DRE of Madeira tourism (2008)" (PDF). Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ Sei Whale, Balaenoptera borealis off Madeira, Portugal. YouTube. 3 January 2013.

- ↑ "Madeira whale and Dolphin watching". www.madeirawindbirds.com. 30 August 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- 1 2 "SEFSTAT – Portal de Estatística". Sefstat.sef.pt. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ "Madeira > Departures > Destinations and Airlines > Destinations and Airlines". Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Administrator. "Porto Santo Line". Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Nidel, Richard (2004). World Music: The Basics. Routledge. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-415-96800-3.

- ↑ Roberts, Helen (1926). Ancient Hawaiian Music. Bernice P. Bishop Museum. pp. 9–10.

- ↑ King, John (2000). "Prolegomena to a History of the 'Ukulele". Ukulele Guild of Hawai'i. Archived from the original on 3 August 2004. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Madeira Espetada". theworldwidegourmet.com. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ T. Stevenson "The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia" pg 340–341 Dorling Kindersley 2005 ISBN 0-7566-1324-8

- ↑ "Labelling of wine and certain other wine sector products". Europa.eu. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

Bibliography

- Pitta, Nicholas Cayetano de Bettencourt (1812). Account of the Island of Madeira. London, UK: C.Stewart Printer.

- Koebel, William Henry (1909). Madeira : old and new. London, UK: Francis Griffiths.

- Dervenn, Claude (1957). Madeira. Translated by Hogarth-Gaute, Frances. London, UK: George G. Harrap and Co.

- Walvin, James (2000). Making the Black Atlantic: Britain and the African Diaspora. London, UK: Cassell.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_May_2007.jpg)