Astrology and astronomy

| Astrology |

|---|

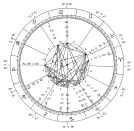

New millennium astrological chart |

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

|

|

Astrology and astronomy were archaically treated together (Latin: astrologia), and were only gradually separated in Western 17th century philosophy (the "Age of Reason") with the rejection of astrology. During the later part of the medieval period, astronomy was treated as the foundation upon which astrology could operate.[1]

Since the 18th century they have come to be regarded as completely separate disciplines. Astronomy, the study of objects and phenomena originating beyond the Earth's atmosphere, is a science[2][3][4] and is a widely studied academic discipline. Astrology, which uses the apparent positions of celestial objects as the basis for the prediction of future events, is defined as a form of divination and is regarded by many as a pseudoscience having no scientific validity.[5][6][7]

Overview

In pre-modern times, most cultures did not make a clear distinction between the two disciplines, putting them both together as one. In ancient Babylonia, famed for its astrology, there were not separate roles for the astronomer as predictor of celestial phenomena, and the astrologer as their interpreter; both functions were performed by the same person. This overlap does not mean that astrology and astronomy were always regarded as one and the same. In ancient Greece, pre-Socratic thinkers such as Anaximander, Xenophanes, Anaximenes, and Heraclides speculated about the nature and substance of the stars and planets. Astronomers such as Eudoxus (contemporary with Plato) observed planetary motions and cycles, and created a geocentric cosmological model that would be accepted by Aristotle. This model generally lasted until Ptolemy, who added epicycles to explain the retrograde motion of Mars. (Around 250 BC, Aristarchus of Samos postulated a proto-heliocentric theory, which would not be reconsidered for nearly two millennia (Copernicus), as Aristotle's geocentric model continued to be favored.) The Platonic school promoted the study of astronomy as a part of philosophy because the motions of the heavens demonstrate an orderly and harmonious cosmos. In the third century BC, Babylonian astrology began to make its presence felt in Greece. Astrology was criticized by Hellenistic philosophers such as the Academic Skeptic Carneades and Middle Stoic Panaetius. However, the notions of the Great Year (when all the planets complete a full cycle and return to their relative positions) and eternal recurrence were Stoic doctrines that made divination and fatalism possible.

In the Hellenistic world, the Greek words 'astrologia' and 'astronomia' were often used interchangeably, but they were conceptually not the same. Plato taught about 'astronomia' and stipulated that planetary phenomena should be described by a geometrical model. The first solution was proposed by Eudoxus. Aristotle favored a physical approach and adopted the word 'astrologia'. Eccentrics and epicycles came to be thought of as useful fictions. For a more general public, the distinguishing principle was not evident and either word was acceptable. For the Babylonian horoscopic practice, the words specifically used were 'apotelesma' and 'katarche', but otherwise it was subsumed under the aristotelian term 'astrologia'.

In his compilatory work Etymologiae, Isidore of Seville noted explicitly the difference between the terms astronomy and astrology (Etymologiae, III, xxvii) and the same distinction appeared later in the texts of Arabian writers.[8] Isidore identified the two strands entangled in the astrological discipline and called them astrologia naturalis and astrologia superstitiosa.

Astrology was widely accepted in medieval Europe as astrological texts from Hellenistic and Arabic astrologers were translated into Latin. In the late Middle Ages, its acceptance or rejection often depended on its reception in the royal courts of Europe. Not until the time of Francis Bacon was astrology rejected as a part of scholastic metaphysics rather than empirical observation. A more definitive split between astrology and astronomy in the West took place gradually in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when astrology was increasingly thought of as an occult science or superstition by the intellectual elite. Because of their lengthy shared history, it sometimes happens that the two are confused with one another even today. Many contemporary astrologers, however, do not claim that astrology is a science, but think of it as a form of divination like the I-Ching, an art, or a part of a spiritual belief structure (influenced by trends such as Neoplatonism, Neopaganism, Theosophy, and Hinduism).

Distinguishing characteristics

The primary goal of astronomy is to understand the physics of the universe. Astrologers use astronomical calculations for the positions of celestial bodies along the ecliptic and attempt to correlate celestial events (astrological aspects, sign positions) with earthly events and human affairs. Astronomers consistently use the scientific method, naturalistic presuppositions and abstract mathematical reasoning to investigate or explain phenomena in the universe. Astrologers use mystical or religious reasoning as well as traditional folklore, symbolism and superstition blended with mathematical predictions to explain phenomena in the universe. The scientific method is not consistently used by astrologers.

Astrologers practice their discipline geocentrically[9][10] and they consider the universe to be harmonious, changeless and static, while astronomers have employed the scientific method to infer that the universe is without a center and is dynamic, expanding outward per the Big Bang theory.[11]

Astrologers believe that the position of the stars and planets determine an individual's personality and future. Astronomers study the actual stars and planets, but have found no evidence supporting astrological theories. Psychologists study personality, and while there are many theories of personality, no mainstream theories in that field are based on astrology. (The Myers-Briggs personality typology, based on the works of Carl Jung, has four major categories that correspond to the astrological elements of fire, air, earth, and water. This theory of personality is used by career counselors and life coaches but not by psychologists.)

Both astrologers and astronomers see Earth as being an integral part of the universe, that Earth and the universe are interconnected as one cosmos (not as being separate and distinct from each other). However, astrologers philosophically and mystically portray the cosmos as having a supernatural, metaphysical and divine essence that actively influences world events and the personal lives of people.[12] Astronomers, as members of the scientific community, cannot use in their scientific articles explanations that are not derived from empirically reproducible conditions, irrespective of their personal convictions.

Historical divergence

For a long time the funding from astrology supported some astronomical research, which was in turn used to make more accurate ephemerides for use in astrology. In Medieval Europe the word Astronomia was often used to encompass both disciplines as this included the study of astronomy and astrology jointly and without a real distinction; this was one of the original Seven Liberal Arts. Kings and other rulers generally employed court astrologers to aid them in the decision making in their kingdoms, thereby funding astronomical research. University medical students were taught astrology as it was generally used in medical practice.

Astronomy and astrology diverged over the course of the 17th through 19th centuries. Copernicus didn't practice astrology (nor empirical astronomy; his work was theoretical[13]), but the most important astronomers before Isaac Newton were astrologers by profession – Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, and Galileo Galilei. Newton most likely rejected astrology, however (as did his contemporary Christiaan Huygens),[14][15][16] and interest in astrology declined after his era, helped by the increasing popularity of a Cartesian, "mechanistic" cosmology in the Enlightenment.

Also relevant here was the development of better timekeeping instruments, initially for aid in navigation; improved timekeeping made it possible to make more exact astrological predictions—predictions which could be tested, and which consistently proved to be false.[17] By the end of the 18th century, astronomy was one of the major sciences of the Enlightenment model, using the recently codified scientific method, and was altogether distinct from astrology.

See also

- History of astronomy

- History of astrology

- Natal chart

- Panchangam

- The Sophia Centre

- Treatise on the Astrolabe

References

- ↑ Pedersen, Olaf (1993). Early physics and astronomy : a historical introduction (Rev. ed.). Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. p. 214. ISBN 0521403405.

- ↑ "astronomy – Britannica Concise". Concise.britannica.com. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ "Ontario Science Centre: Glossary of Useful Scientific Terms". Ontariosciencecentre.ca. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ "Outer Space Glossary". Library.thinkquest.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ "astrology – Britannica Concise". Concise.britannica.com. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ "The Skeptic Dictionary's entry on astrology". Skepdic.com. 7 February 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "Activities With Astrology". Astrosociety.org. 5 December 1985. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural". Randi.org. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Kruszelnicki, Karl S. (16 December 2004). "Astrology or Star Struck". Australia: ABC. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ "Astrology". Bad Astronomy. 2 July 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ S. Pines (September 1964). "The Semantic Distinction between the Terms Astronomy and Astrology according to al-Biruni", Isis 55 (3), p. 343-349.

- ↑ "Astrology Terminology Dictionary". Skyviewzone.com. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ "Astronomy For Astrologers". AstrologyClub.Org. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Big Bang and the Expansion of the Universe". Atlasoftheuniverse.com. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ "Realities in Astrology". Wisdomsgoldenrod.org. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ Westman argued that his interest was indeed astrological and points that it would be an historical exception if he did not practice astrology; however there is just an indirect mention on record, see Westman R. (2011), The Copernican Question, University of California Press

- ↑ "Rebuttal of Newton's astrology interests". Skepticreport.com. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ (D.T. Whiteside, M.A. Hoskin & A. Prag (eds.), The Mathematical Papers of Isaac Newton (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1967), vol. 1, pp. 15–19)

- ↑ It is a commonly held belief among astrologers that Isaac Newton had an interest in astrology. However, Newton's writings fail to mention the subject and the handful of books in his possession that contained references to astrology were primarily concerned with other subjects such as the writings of Hermes Trismegistus (and mentioned astrology only in passing). In an interview with John Conduitt, Newton said that as a young student, he had read a book on astrology, and was "soon convinced of the vanity & emptiness of the pretended science of Judicial astrology".

- ↑ "In our time: Astrology". BBC. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

Further reading

- Eade, J. C. (1984). The Forgotten Sky: A Guide to Astrology in English Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Losev, A. (2012). "'Astronomy' or 'astrology': a brief history of an apparent confusion". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 15 (1): 42–46. arXiv:1006.5209

. Bibcode:2012JAHH...15...42L.

. Bibcode:2012JAHH...15...42L. - North, John David (1988). Chaucer's Universe. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- "What's the difference between astronomy and astrology?". American Astronomical Society. Retrieved 2014-08-17.