Ascension of Jesus

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the Gospels |

|---|

|

|

In rest of the NT |

|

Portals: |

The Ascension of Jesus (anglicized from the Vulgate Latin Acts 1:9-11 section title: Ascensio Iesu) is the departure of Christ from Earth into the presence of God.[1] The well-known narrative in Acts 1 takes place 40 days after the Resurrection: Jesus, in the company of the disciples, is taken up in their sight after warning them to remain in Jerusalem until the coming of the Holy Spirit; as he ascends a cloud hides him from their view, and two men in white appear to tell them that he will return "in the same way you have seen him go into heaven."[2]

Heavenly ascents were fairly common in the time of Jesus,[3] signifying divine approval or the deification of an exceptional man.[4] In the Christian tradition, reflected in the major Christian creeds and confessional statements, the ascension is connected with the exultation of Jesus, meaning that through his ascension Jesus took his seat at the right hand of God:[5] "He ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty." The Feast of the Ascension is celebrated on the 40th day of Easter, always a Thursday;[5] the Orthodox tradition has a different calendar up to a month later than in the Western tradition, and while the Anglican communion continues to observe the feast, most Protestant churches have abandoned it.[6][7] The Ascension of Jesus is an important theme in Christian art, the ascending Jesus often shown blessing an earthly group below him to signify his blessing the entire Church.[8]

Background

The world of the Ascension is a three-part universe with the heavens above, a flat earth centered on Jerusalem in the middle, and the underworld below.[9][10][11] Heaven was separated from the earth by the firmament, the visible sky, a solid inverted bowl where God's throne sat "on the vaulted roof of earth."(Isaiah 40:22).[12][13] Humans looking up from earth saw the floor of heaven, made of clear blue lapis-lazuli (Exodus 24:9-10), as was God's throne (Ezekiel 1:26).[14]

Heavenly ascents were fairly common in the time of Jesus,[3] signifying the means whereby a prophet could attain access to divine secrets, or divine approval granted to an exceptionally righteous individual, or the deification of an exceptional man.[4] Figures familiar to Jews would have included Enoch (from the Book of Genesis and a popular non-Biblical work called 1 Enoch), the 5th century sage Ezra, Baruch the companion of the prophet Jeremiah (from a work called 2 Baruch, in which Baruch is promised he will ascend to heaven after 40 days)), Levi the ancestor of priests, the Teacher of Righteousness from the Qumran community, as well as Elijah and Moses, who was deified on entering heaven, and the children of Job, who according to the Testament of Job ascended heaven following their resurrection from the dead.[15][16] Non-Jewish readers would have been familiar with the case of the emperor Augustus, whose ascent was witnessed by Senators, Romulus the founder of Rome, who, like Jesus, was taken to heaven in a cloud, the Greek hero Heracles (Hercules), and many others.[17]

Biblical accounts

| Part of a series on |

| Death and Resurrection of Jesus |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

There is a broad consensus among scholars that the brief Ascension account in the Gospel of Mark is a later addition to the original version of that gospel.[18] Luke-Acts, a single work from the same anonymous author, provides the only detailed account of the Ascension.[19][1] Luke 24 tells how Jesus leads the eleven disciples to Bethany, a village on the Mount of Olives not far from Jerusalem, where he instructs them to remain in Jerusalem until the coming of the Holy Spirit and blesses them. "And it came to pass, while he blessed them, he parted from them, and was carried up into heaven. And they worshiped him, and returned to Jerusalem with great joy."

Acts 1 describes a meal on the Mount of Olives, where Jesus commands the disciples to await the coming of the Holy Spirit, a cloud takes him upward from sight, and two men in white appear to tell them (the disciples) that he will return "in the same way you have seen him go into heaven."[2] Luke and Acts appear to describe the same event, but present quite different chronologies, Luke placing it on the same day as the Resurrection and Acts forty days afterwards;[20] various proposals have been put forward to resolve the contradiction, but the question remains open.[21]

The Gospel of John has three references to ascension in Jesus' own words: "No one has ascended into heaven but he who descended from heaven, the son of man" (John 3:13); "What if you (the disciples) were to see the son of man ascending where he was before?" (John 6:62); and to Mary Magdalene after his Resurrection, "Do not hold me, for I not yet ascended to my father..." (John20:17).[1] In the first and second Jesus is claiming to be the apocalyptic "one like a son of man" of Daniel 7;[22] the last has mystified commentators – why should Mary be prohibited from touching the risen but not yet ascended Christ, while Thomas is later invited to do so?[23]

Various epistles (Romans 8:34, Ephesians 1:19-20, Colossians 3:1, Philippians 2:9-11, 1 Timothy 3:16, and 1 Peter 3:21-22) also refer to an Ascension, seeming, like Luke-Acts and John, to equate it with the post-resurrection "exultation" of Jesus to the right hand of God.[17]

Christian theology

The common thread linking all the New Testament Ascension references, reflected in the major Christian creeds and confessional statements, is the exultation of Jesus, meaning that through his ascension Jesus took his seat at the right hand of God in Heaven:[5] "He ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty." It is interpreted more broadly as the culmination of the Mystery of the Incarnation, marking the completion of Jesus' physical presence among his apostles and consummating the union of God and man, as expressed in the Second Helvetic Confession:[24]

- Christ Is Truly Ascended Into Heaven. We believe that our Lord Jesus Christ, in his same flesh, ascended above all visible heavens into the highest heaven, that is, the dwelling-place of God and the blessed ones, at the right hand of God the Father. Although it signifies an equal participation in glory and majesty, it is also taken to be a certain place about which the Lord, speaking in the Gospel, says: 'I go to prepare a place for you' (John 14:2). The apostle Peter also says: 'Heaven must receive Christ until the time of restoring all things' (Acts 3:21).

Despite this, the Ascension itself has become an embarrassment.[25] As expressed in a famous statement by theologian Rudolf Bultmann in his essay The New Testament and Mythology: "We no longer believe in the three-storied universe which the creeds take for granted... No one who is old enough to think for himself supposes that God lives in a local heaven ... And if this is so, the story of Christ's ... ascension into heaven is done with."[26] Modern theologians have therefore de-mythologised their theology, abandoning a God who sits enthroned above Jerusalem for a heaven which is "the endless, self-sustaining life of God" and the Ascension "an emblem in space and time of God's eternal life."[27]

Liturgy: Feast of the Ascension

The Feast of the Ascension is one of the ecumenical (i.e., universally celebrated) feasts of the Christian liturgical year, along with the Passion, Easter, and Pentecost. Ascension Day is traditionally celebrated on the sixth Thursday after Easter Sunday, the fortieth day from Easter day, although some Roman Catholic provinces have moved the observance to the following Sunday to facilitate the obligation to take Mass. Saint Jerome held that it was of Apostolic origin, but in fact the Ascension was originally part of Pentecost (the coming of the Holy Spirit, and developed as a separate celebration only slowly from the late 4th century onward. In the Catholic tradition it begins with a three-day "rogation" to ask for God's mercy, and the feast itself includes a procession of torches and banners symbolising Christ's journey to the Mount of Olives and entry into heaven, the extinguishing of the Paschal candle, and an all-night vigil; white is the liturgical colour. The orthodox tradition has a slightly different calendar up to a month later than in the Western tradition; the Anglican communion continues to observe the feast, but most Protestant churches have abandoned the traditional Christian calendar of feasts.[6][7]

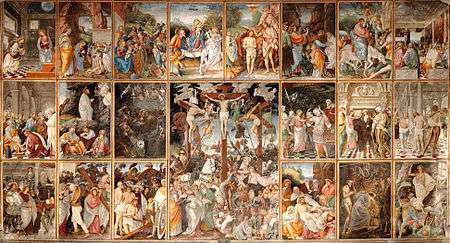

In Christian art

The Ascension has been a frequent subject in Christian art.[28] By the 6th century the iconography of the Ascension had been established and by the 9th century Ascension scenes were being depicted on domes of churches.[29][30] The Rabbula Gospels (c. 586) include some of the earliest images of the Ascension.[30] Many ascension scenes have two parts, an upper (Heavenly) part and a lower (earthly) part. The ascending Christ may be carrying a resurrection banner or make a sign of benediction with his right hand.[31] The blessing gesture by Christ with his right hand is directed towards the earthly group below him and signifies that he is blessing the entire Church.[8] In the left hand, he may be holding a Gospel or a scroll, signifying teaching and preaching.[8]

The Eastern Orthodox portrayal of the Ascension is a major metaphor for the mystical nature of the Church.[32] In many Eastern icons the Virgin Mary is placed at the center of the scene in the earthly part of the depiction, with her hands raised towards Heaven, often accompanied by various Apostles.[32] The upwards-looking depiction of the earthly group matches the Eastern liturgy on the Feast of the Ascension: "Come, let us rise and turn our eyes and thoughts high ..."[8]

Eastern tradition

-

Rabbula Gospels 6th century

-

.jpg)

Andrei Rublev, 1408

-

19th century Macedonian icon, Bitola, Macedonia

-

Drogo Sacramentary, c. 850

-

Armenian Gospel manuscript, 1609

Western tradition

-

Pietro Perugino 1496–1500

-

Garofalo, 1520

-

Rembrandt, 1636

-

Rosary Basilica, Lourdes, 19th century

Olivet and the Chapel of the Ascension

The traditional site of the Ascension is Mount Olivet (the "Mount of Olives"), on which the village of Bethany sits. Before the conversion of Constantine in 312 AD, early Christians honored the Ascension of Christ in a cave on the Mount, and by 384 the Ascension was venerated on the present site, uphill from the cave.[33]

Around the year 390 a wealthy Roman woman named Poimenia financed construction of the original church called "Eleona Basilica" (elaion in Greek means "olive garden", from elaia "olive tree," and has an oft-mentioned similarity to eleos meaning "mercy"). This church was destroyed by Sassanid Persians in 614. It was subsequently rebuilt, destroyed, and rebuilt again by the Crusaders. This final church was later destroyed by Muslims, leaving only a 12x12 meter octagonal structure (called a martyrium—"memorial"—or "Edicule") that remains to this day.[34] The site was ultimately acquired by two emissaries of Saladin in the year 1198 and has remained in the possession of the Islamic Waqf of Jerusalem ever since.

The Chapel of the Ascension today is a Christian and Muslim holy site now believed to mark the place where Jesus ascended into heaven; in the small round church/mosque is a stone imprinted with the footprints of Jesus.[33] The Russian Orthodox Church also maintains a Convent of the Ascension on the top of the Mount of Olives.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ascension of Jesus Christ. |

- Ascension Parish

- Assumption of Mary

- Chronology of Jesus

- Church of the Ascension (disambiguation)

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Rapture

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Session of Christ

- Transfiguration of Jesus

- Post-Resurrection appearances of Jesus

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Holwerda 1979, p. 310.

- 1 2 Muller 2016, p. 113-114.

- 1 2 McDonald 2004, p. 22.

- 1 2 Aune 2003a, p. 65.

- 1 2 3 Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 114.

- 1 2 Quast 2011, p. 45.

- 1 2 Stokl-Ben Ezra 2007, p. 286.

- 1 2 3 4 Ouspensky & Lossky 1999, p. 197.

- ↑ Wright 2002, p. 54.

- ↑ Schadewald 2008, p. 96.

- ↑ Najman 2014, p. 92.

- ↑ Pennington 2007, p. 41-42.

- ↑ Schadewald 2008, p. 143.

- ↑ & Wright 2002, p. 54,56.

- ↑ Munoa 2000, p. 109.

- ↑ Zwiep 2016, p. 16.

- 1 2 McDonald 2004, p. 21.

- ↑ Cresswell 2013, p. unpaginated.

- ↑ Thompson 2010, p. 319.

- ↑ Seim & Økland 2009, p. 24.

- ↑ Muller 2016, p. 113.

- ↑ Köstenberger, p. 85.

- ↑ Quast 1991, p. 134.

- ↑ Dawson 2004, p. 217-218.

- ↑ Farrow 2004, p. 9.

- ↑ Lincoln 1981, p. 4.

- ↑ Packer 2008, p. unpaginated.

- ↑ Becchio & Schadé 2006, p. unpaginated.

- ↑ Baggley 2000, p. 137-138.

- 1 2 Jensen 2008, p. 51-53.

- ↑ Earls 1987, p. 26-27.

- 1 2 Nes 2005, p. 87.

- 1 2 Web: 4 April 2010. Chapel of the Ascension, Jerusalem(Sacred destinations)

- ↑ Web: 4 April 2010. Chapel of the Ascension

Bibliography

- Aune, David (2003a). "Ascent, heavenly". The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early Christian Literature and Rhetoric. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664219178.

- Aune, David (2003b). "Cosmology". The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early Christian Literature and Rhetoric. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664219178.

- Baggley, John (2000). Festival Icons for the Christian Year. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881412017.

- Becchio, Bruno; Schadé, Johannes P. (2006). "Ascension". Encyclopedia of World Religions. Foreign Media Group. ISBN 9781601360007.

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521007207.

- Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426724756.

- Collins, Adela Yarbro (2000). Cosmology and Eschatology in Jewish and Christian Apocalypticism. BRILL. ISBN 9004119272.

- Cresswell, Peter (2013). The Invention of Jesus: How the Church Rewrote the New Testament. Duncan Baird Publishers. ISBN 9781780286211.

- Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). "Ascension". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802903.

- Dawson, Gerrit (2004). Jesus Ascended: The Meaning of Christ's Continuing Incarnation. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567119872.

- Earls, Irene (1987). Renaissance Art: A Topical Dictionary. ABC-CLIO.

- Farrow, Douglas (2011). Ascension Theology. Bloomsbury.

- Farrow, Douglas (2004). Ascension And Ecclesia. A&C Black.

- Holwerda, D.E. (1979). "Ascension". In Bromiley, Geoffrey. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Eerdmans.

- Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Eerdmans.

- Knight, Douglas A.; Levine, Amy-Jill (2011). The Meaning of the Bible: What the Jewish Scriptures and Christian Old Testament Can Teach Us. HarperCollins.

- Jensen, Robin M. (2008). "Art in Early Christianity". In Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O. The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Köstenberger, Andreas J. (2004). John. Baker Academic.

- Lee, Sang Meyng (2010). The Cosmic Drama of Salvation. Mohr Siebeck.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2004). Paradise Now and Not Yet. Cambridge University Press.

- McDonald, Lee Martin (2004). "Acts". In Combes, Isobel A. H.; Gurtner, Daniel M. Bible Knowledge Background Commentary. David C Cook.

- Müller, Mogens (2016). "Acts as biblical rewriting of the gospels and Paul's letters". In Müller, Mogens; Nielsen, Jesper Tang. Luke's Literary Creativity. Bloomsbury.

- Munoa, Phillip (2000). "Ascension". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans.

- Najman, Hindy (2014). Losing the Temple and Recovering the Future: An Analysis of 4 Ezra. Cambridge University Press.

- Nes, Solrunn (2005). The Mystical Language of Icons. Eerdmans.

- Ouspensky, Léonide; Lossky, Vladimir (1982). The Meaning of Icons. St Vladimir's Seminary Press.

- Packer, J.I. (2008). Affirming the Apostles' Creed. Crossway.

- Park, Eung Chun (2003). Either Jew Or Gentile: Paul's Unfolding Theology of Inclusivity. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Pennington, Jonathan T. (2007). Heaven and earth in the Gospel of Matthew. BRILL.

- Quast, Kevin (2011). "Ascension Day". In Melton, J. Gordon. Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO.

- Quast, Kevin (1991). Reading the Gospel of John. Paulist Press.

- Seim, Turid Karlsen; Økland, Jorunn (2009). Metamorphoses: Resurrection, Body and Transformative Practices in Early Christianity. Walter de Gruyter.

- Schadewald, Robert J. (2008). Worlds of Their Own. Xlibris Corporation.

- Seim, Turid Karlsen; Økland, Jorunn (2009). Metamorphoses: Resurrection, Body and Transformative Practices in Early Christianity. Walter de Gruyter.

- Stokl-Ben-Ezra, Daniel (2007). "Parody and Polemics on Pentecost". In Gerhards, Albert; Leonhard, Clemens. Jewish and Christian Liturgy and Worship. BRILL. ISBN 9789047422419.

- Thompson, Richard P. (2010). "Luke-Acts: The Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles". In Aune, David E. The Blackwell Companion to The New Testament. Wiley–Blackwell. ISBN 9781444318944.

- Vermes, Geza (2001). The Changing Faces of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141912585.

- Wright, J. Edward (2002). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198029816.

- Zwiep, Arie W. (2016). "Ascension scholarship past present and future". In Pao, David W.; Bryan, David K. Ascent into Heaven in Luke-Acts: New Explorations of Luke's Narrative Hinge. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781506418964.

- Zwiep, Arie W. (1997). The Ascension of the Messiah in Lukan Christology. BRILL. ISBN 9004108971.

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Ascension

- The Ascension of the Lord S. V. Bulgakov, Manual for Church Servers (theology and symbolism of the Feast)

- The Chapel of the Ascension Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem

- Chapel of the Ascension, Jerusalem Detailed description, history and photos

- Convent of the Ascension Jerusalem Mission, Russian Orthodox Church

- Kerygma and Myth by Rudolf Bultmann and Five Critics (1953) online edition - containing the essay "The New Testament and Mythology" with critical analyses and Bultmann's response