Kiwi

| Kiwi | |

|---|---|

| |

| North Island brown kiwi (Apteryx mantelli) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Novaeratitae |

| Order: | Apterygiformes Haeckel, 1866 |

| Family: | Apterygidae Gray, 1840[1] |

| Genus: | Apteryx Shaw, 1813[1] |

| Type species | |

| Apteryx australis Shaw & Nodder, 1813[2] | |

| Species | |

|

Apteryx haastii Great spotted kiwi | |

| |

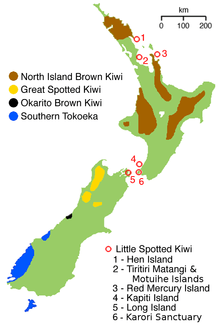

| The distribution of each species of kiwi | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Stictapteryx Iredale & Mathews, 1926 | |

Kiwi (pronounced /kiːwiː/) or kiwis are flightless birds native to New Zealand, in the genus Apteryx and family Apterygidae. At around the size of a domestic chicken, kiwi are by far the smallest living ratites (which also consist of ostriches, emus, rheas, and cassowaries), and lay the largest egg in relation to their body size of any species of bird in the world.[4] DNA sequence comparisons have yielded the surprising conclusion that kiwi are much more closely related to the extinct Malagasy elephant birds than to the moa with which they shared New Zealand.[5] There are five recognised species, two of which are currently vulnerable, one of which is endangered, and one of which is critically endangered. All species have been negatively affected by historic deforestation but currently the remaining large areas of their forest habitat are well protected in reserves and national parks. At present, the greatest threat to their survival is predation by invasive mammalian predators.

The kiwi is a national symbol of New Zealand, and the association is so strong that the term Kiwi is used internationally as the colloquial demonym for New Zealanders.[6]

Etymology

The Māori language word kiwi (/ˈkiːwiː/ KEE-wee)[7] is generally accepted to be "of imitative origin" from the call.[8] However, some linguists derive the word from Proto-Nuclear Polynesian *kiwi, which refers to Numenius tahitiensis, the bristle-thighed curlew, a migratory bird that winters in the tropical Pacific islands.[9] With its long decurved bill and brown body, the curlew resembles the kiwi. So when the first Polynesian settlers arrived, they may have applied the word kiwi to the new-found bird.[10] The genus name Apteryx is derived from Ancient Greek "without wing": a-, "without" or "not"; pterux, "wing".[11]

The name is usually uncapitalised, with the plural either the anglicised "kiwis"[12] or, consistent with the Māori language, appearing as "kiwi" without an "-s".[13]

Taxonomy and systematics

Although it was long presumed that the kiwi was closely related to the other New Zealand ratites, the moa, recent DNA studies have identified its closest relative as the extinct elephant bird of Madagascar,[5][14] and among extant ratites, the kiwi is more closely related to the emu and the cassowaries than to the moa.[5][15]

Research published in 2013 on an extinct genus, Proapteryx, known from the Miocene deposits of the Saint Bathans Fauna, found that it was smaller and probably capable of flight, supporting the hypothesis that the ancestor of the kiwi reached New Zealand independently from moas, which were already large and flightless by the time kiwi appeared.[16]

Species

There are five known species of kiwi, as well as a number of subspecies.

| ||||||||||

| | ||||||||||

| |

| |||||||||

| |

Relationships in the genus Apteryx[17]

- The largest species is the great spotted kiwi or Roroa, Apteryx haastii, which stands about 45 cm (18 in) high and weighs about 3.3 kg (7.3 lb) (males about 2.4 kg (5.3 lb)). It has grey-brown plumage with lighter bands. The female lays just one egg, which both parents then incubate. The population is estimated to be over 20,000, distributed through the more mountainous parts of northwest Nelson, the northern West Coast, and the Southern Alps.[18]

- The small little spotted kiwi, Apteryx owenii is unable to withstand predation by introduced pigs, stoats and cats, which have led to its extinction on the mainland. About 1350 remain on Kapiti Island. It has been introduced to other predator-free islands and appears to be becoming established with about 50 'Little Spots' on each island. A docile bird the size of a bantam, it stands 25 cm (9.8 in) high and the female weighs 1.3 kg (2.9 lb). She lays one egg, which is incubated by the male.[19]

- The Okarito kiwi, also known as the rowi or Okarito brown kiwi, Apteryx rowi, first identified as a new species in 1994,[20] is slightly smaller, with a greyish tinge to the plumage and sometimes white facial feathers. Females lay as many as three eggs in a season, each one in a different nest. Male and female both incubate. The distribution of these kiwi is limited to a small area on the west coast of the South Island of New Zealand. However, studies of ancient DNA have revealed that, in prehuman times, it was far more widespread up the west coast of the South Island and was present in the lower half of the North Island, where it was the only kiwi species detected.[21]

- The southern brown kiwi, Tokoeka, or Common kiwi, Apteryx australis, is a relatively common species of kiwi, known from south and west parts of the South Island, that occurs at most elevations. It is approximately the size of the great spotted kiwi and is similar in appearance to the brown kiwi, but its plumage is lighter in colour. Ancient DNA studies have shown that, in prehuman times, the distribution of this species included the east coast of South Island.[21] There are several subspecies of the Tokoeka recognised:

- The Stewart Island southern brown kiwi, Apteryx australis lawryi, is a subspecies of Tokoeka from Stewart Island/Rakiura.

- The Northern Fiordland southern brown kiwi (Apteryx australis ?) and Southern Fiordland tokoeka (Apteryx australis ?) live in the remote southwest part of the South Island known as Fiordland. These sub-species of tokoeka are relatively common and are nearly 40 cm (16 in) tall.

- The Haast southern brown kiwi, Haast tokoeka, Apteryx australis ‘Haast’, is the rarest subspecies of kiwi with only about 300 individuals. It was identified as a distinct form in 1993. It occurs only in a restricted area in the South Island's Haast Range of the Southern Alps at an altitude of 1,500 m (4,900 ft). This form is distinguished by a more strongly downcurved bill and more rufous plumage.

- The North Island brown kiwi, Apteryx mantelli or Apteryx australis before 2000 (and still in some sources), is widespread in the northern two-thirds of the North Island and, with about 35,000 remaining,[22] is the most common kiwi. Females stand about 40 cm (16 in) high and weigh about 2.8 kg (6.2 lb), the males about 2.2 kg (4.9 lb). The North Island brown has demonstrated a remarkable resilience: it adapts to a wide range of habitats, even non-native forests and some farmland. The plumage is streaky red-brown and spiky. The female usually lays two eggs, which are incubated by the male.

Description

Their adaptation to a terrestrial life is extensive: like all the other ratites (ostrich, emu, rhea and cassowary), they have no keel on the sternum to anchor wing muscles. The vestigial wings are so small that they are invisible under the bristly, hair-like, two-branched feathers. While most adult birds have bones with hollow insides to minimise weight and make flight practicable, kiwi have marrow, like mammals and the young of other birds. With no constraints on weight due to flight requirements, brown kiwi females carry and lay a single egg that may weigh as much as 450 g (16 oz). Like most other ratites, they have no uropygial gland (preen gland). Their bill is long, pliable and sensitive to touch, and their eyes have a reduced pecten. Their feathers lack barbules and aftershafts, and they have large vibrissae around the gape. They have 13 flight feathers, no tail and a small pygostyle. Their gizzard is weak and their caecum is long and narrow.[2]

Unlike virtually every other palaeognath, which are generally small-brained by bird standards, kiwi have proportionally large encephalisation quotients. Hemisphere proportions are even similar to those of parrots and songbirds, though there is no evidence of similarly complex behaviour.[23]

Behaviour and ecology

Before the arrival of humans in the 13th century or earlier, New Zealand's only endemic mammals were three species of bat, and the ecological niches that in other parts of the world were filled by creatures as diverse as horses, wolves and mice were taken up by birds (and, to a lesser extent, reptiles, insects and gastropods).[24]

Kiwi are shy and usually nocturnal. Their mostly nocturnal habits may be a result of habitat intrusion by predators, including humans. In areas of New Zealand where introduced predators have been removed, such as sanctuaries, kiwi are often seen in daylight. They prefer subtropical and temperate podocarp and beech forests, but they are being forced to adapt to different habitat, such as sub-alpine scrub, tussock grassland, and the mountains.[2] Kiwi have a highly developed sense of smell, unusual in a bird, and are the only birds with nostrils at the end of their long beaks. Kiwi eat small invertebrates, seeds, grubs, and many varieties of worms. They also may eat fruit, small crayfish, eels and amphibians. Because their nostrils are located at the end of their long beaks, kiwi can locate insects and worms underground using their keen sense of smell, without actually seeing or feeling them.[2]

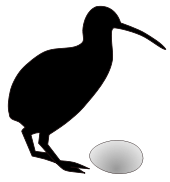

Once bonded, a male and female kiwi tend to live their entire lives as a monogamous couple. During the mating season, June to March, the pair call to each other at night, and meet in the nesting burrow every three days. These relationships may last for up to 20 years.[25] They are unusual among other birds in that, along with some raptors, they have a functioning pair of ovaries. (In most birds and in platypuses, the right ovary never matures, so that only the left is functional.[2][26][27]) Kiwi eggs can weigh up to one-quarter the weight of the female. Usually, only one egg is laid per season. The kiwi lays the biggest egg in proportion to its size of any bird in the world,[28] so even though the kiwi is about the size of a domestic chicken, it is able to lay eggs that are about six times the size of a chicken's egg.[29] The eggs are smooth in texture, and are ivory or greenish white.[30] The male incubates the egg, except for the Great Spotted Kiwi, A. haastii, in which both parents are involved. The incubation period is 63–92 days.[2] Producing the huge egg places significant physiological stress on the female; for the thirty days it takes to grow the fully developed egg, the female must eat three times her normal amount of food. Two to three days before the egg is laid there is little space left inside the female for her stomach and she is forced to fast.[31]

Status and conservation

Nationwide studies show that, on average, only five percent of kiwi chicks survive to adulthood. However, in areas under active pest management, survival rates for North Island brown kiwi can be far higher. For example, prior to a joint 1080 poison operation undertaken by DOC and the Animal Health Board in Tongariro Forest in 2006, 32 kiwi chicks were radio-tagged. 57% of the radio-tagged chicks survived to adulthood. Thanks to ongoing pest control, the adult kiwi population at Tongariro has almost doubled since 1998.

Sanctuaries

In 2000, the Department of Conservation set up five kiwi sanctuaries focused on developing methods to protect kiwi and to increase their numbers.

- There are three kiwi sanctuaries in the North Island:

- Whangarei Kiwi Sanctuary (for Northland brown kiwi)

- Moehau Kiwi Sanctuary on the Coromandel Peninsula (Coromandel brown kiwi)

- Tongariro Kiwi Sanctuary near Taupo (western brown kiwi)

- and two in the South Island:

- Okarito Kiwi Sanctuary (Okarito kiwi)

- Haast Kiwi Sanctuary (Haast tokoeka)

A number of other mainland conservation islands and fenced sanctuaries have significant populations of kiwi, including:

- Zealandia fenced sanctuary in Wellington (little spotted kiwi)

- Maungatautari Restoration Project in Waikato (brown kiwi)

- Bushy Park Forest Reserve near Kai Iwi, Whanganui (brown kiwi)

- Otanewainuku Forest in the Bay of Plenty (brown kiwi)

- Hurunui Mainland Island, south branch, Hurunui River, North Canterbury (great spotted kiwi)

North island brown kiwi were introduced to the Cape Sanctuary in Hawke's Bay between 2008 and 2011, which in turn provided captive-raised chicks that were released back into Maungataniwha Native Forest.[32]

Operation "Nest Egg"

Operation Nest Egg is a programme run by the BNZ Save the Kiwi Trust—a partnership between the Bank of New Zealand, the Department of Conservation and the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society. Kiwi eggs and chicks are removed from the wild and hatched and/or raised in captivity until big enough to fend for themselves—usually when they weigh around 1200 grams (42 ounces). They are then returned to the wild. An Operation Nest Egg bird has a 65% chance of surviving to adulthood—compared to just 5% for wild-hatched and raised chicks.[33] The tool is used on all kiwi species except little spotted kiwi.

1080 poison

In 2004, anti-1080 activist Phillip Anderton posed for the New Zealand media with a kiwi he claimed had been poisoned. An investigation revealed that Anderton lied to journalists and the public.[34] He had used a kiwi that had been caught in a possum trap. Extensive monitoring shows that kiwi are not at risk from the use of biodegradable 1080 poison.[35]

Threats

Introduced mammalian predators, namely stoats, dogs, ferrets, and cats, are the number one threat to kiwi. Other threats include habitat modification/loss and motor vehicle strike. The restricted distribution and small size of some kiwi populations increases their vulnerability to inbreeding.

Stoats are responsible for approximately half of kiwi chick deaths in many areas through New Zealand. Cats also to a lesser extent prey on kiwi chicks. Research has shown that the combined effect of predators and other mortality (accidents etc.) results in less than 5% of kiwi chicks surviving to adulthood.[36] Young kiwi chicks are vulnerable to stoat predation until they reach about 1–1.2 kg in weight, at which time they can usually defend themselves.

Ferrets and dogs often kill adult kiwi. These predators can cause large and abrupt declines in populations. In particular, dogs find the distinctive strong scent of kiwi irresistible and easy to track, such that they can catch and kill kiwi in seconds. Motor vehicle strike is a threat to all kiwi where roads cross through their habitat. Badly set possum traps often kill or maim kiwi.[37]

Relationship to humans

The Māori traditionally believed that kiwi were under the protection of Tane Mahuta, god of the forest. They were used as food and their feathers were used for kahu kiwi—ceremonial cloaks.[38] Today, while kiwi feathers are still used, they are gathered from birds that die naturally or through road accidents or predation, or from captive birds.[39] Kiwi are no longer hunted and some Maori consider themselves the birds' guardians.[10]

Scientific documentation

The first kiwi specimen to be studied by Europeans was a kiwi skin brought to George Shaw by Captain Andrew Barclay aboard the ship Providence, who was reported to have been given it by a sealer in Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) around 1811. George Shaw gave the bird its scientific name and drew sketches of the way he imagined a live bird to look which appeared as plates 1057 and 1058 in volume 24 of The Naturalist's Miscellany in 1813.[40]

Zoos

In 1851, London Zoo became the first zoo to keep kiwi. The first captive breeding took place in 1945.[41] As of 2007 only 13 zoos outside New Zealand hold kiwi.[42] The Frankfurt Zoo has 12, the Berlin Zoo has seven, Walsrode Bird Park has one, the Avifauna Bird Park in the Netherlands has three, the San Diego Zoo has five, the San Diego Zoo Safari Park has one, the National Zoo in Washington, DC has eleven, the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute has one, and the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium has three.[43][44]

As a national symbol

The kiwi as a symbol first appeared in the late 19th century in New Zealand regimental badges. It was later featured in the badges of the South Canterbury Battalion in 1886 and the Hastings Rifle Volunteers in 1887. Soon after, the kiwi appeared in many military badges; and in 1906, when Kiwi Shoe Polish was widely sold in the UK and the US, the symbol became more widely known.

During the First World War, the name "kiwi" for New Zealand soldiers came into general use, and a giant kiwi (now known as the Bulford kiwi), was carved on the chalk hill above Sling Camp in England. Usage has become so widespread that all New Zealanders overseas and at home are now commonly referred to as "Kiwis".[45]

The kiwi has since become the most well-known national symbol for New Zealand, and the bird is prominent in the coat of arms, crests and badges of many New Zealand cities, clubs and organisations; at the national level, the red silhouette of a kiwi is in the centre of the roundel of the Royal New Zealand Air Force.[30][46] The kiwi is featured in the logo of the New Zealand Rugby League, and the New Zealand national rugby league team are nicknamed the Kiwis.

The reverse of a New Zealand dollar coin contains an image of a kiwi, and in currency trading the New Zealand dollar is often referred to as "the kiwi".[47]

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 Brands, Sheila (14 August 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Family Apterygidae". Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Davies, S.J.J.F. (2003). "8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins". In Hutchins, Michael. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 89–90. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.

- ↑ Gill (2010). "Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica" (PDF) (4th ed.). Te Papa Press. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ "Birds: Kiwi". San Diego Zoo. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- 1 2 3 Mitchell, K. J.; Llamas, B.; Soubrier, J.; Rawlence, N. J.; Worthy, T. H.; Wood, J.; Lee, M. S. Y.; Cooper, A. (2014-05-23). "Ancient DNA reveals elephant birds and kiwi are sister taxa and clarifies ratite bird evolution". Science. 344 (6186): 898–900. doi:10.1126/science.1251981. PMID 24855267.

- ↑ "Kiwis/Kiwi - New Zealand Immigration Service (Summary of Terms)". Glossary.immigration.govt.nz. Retrieved 2012-09-13.

- ↑ "Kiwi", Unabridged Dictionary, Random House, 2006

- ↑ "Kiwi", The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.), Houghton Mifflin, 2006

- ↑ "kiwi", Polynesian Lexicon Project Online, NZ

- 1 2 "Kiwi a Maori", About the bird, Save the kiwi

- ↑ Gotch, AF (1995) [1979]. "Kiwis". Latin Names Explained. A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. London: Facts on File. p. 179. ISBN 0-8160-3377-3.

- ↑ "the definition of kiwis". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Please don't eat Kiwis". Another Spectrum. 17 August 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Little kiwi, huge extinct elephant bird were birds of a feather, IN: The Times of India

- ↑ News in Science, AU: ABC

- ↑ New Zealand. "Did small kiwi fly from Australia? - Canterbury Museum - New Zealand Natural and Human Heritage. Christchurch, NZ". Canterbury Museum. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- ↑ "Great Spotted Kiwi Classification". University of Wisconsin. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Apteryx haastii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Apteryx owenii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ "Rowi: New Zealand native land birds". New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- 1 2 Shepherd, L.D. & Lambert, D.M. (2008) Ancient DNA and conservation: lessons from the endangered kiwi of New Zealand Molecular Ecology 17, 2174–84

- ↑ BirdLife International (2008). "Northern Brown Kiwi". BirdLife Species Factsheet. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ↑ Corfield, J.; Wild, J.M.; Hauber M.E. & Kubke, M.F. (2008). "Evolution of brain size in the Palaeognath lineage, with an emphasis on New Zealand ratites". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 71 (2): 87–99. doi:10.1159/000111456.

- ↑ Kolbert, Elizabeth (22 December 2014). "The Big Kill". The New Yorker. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ Save the Kiwi, NZ, formerly Kiwi Recovery.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, F.L., (1934). Unilateral and bilateral ovaries in raptorial birds. The Wilson Bulletin, 46(1): 19-22

- ↑ Kinsky, F.C., (1971). The consistent presence of paired ovaries in the Kiwi (Apteryx) with some discussion of this condition in other birds. Journal of Ornithology 112(3): 334–357.

- ↑ "Wilderness New Zealand", Official Guide Book, Auckland Zoo

- ↑ Save the kiwi

- 1 2 "The Kiwi Bird, New Zealand's Indigenous Flightless Bird". Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ↑ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press

- ↑ http://www.naturespace.org.nz/history/history-of-cape-sanctuary

- ↑ Operation Nest Egg, NZ: Save the wiki

- ↑ Macbrayne, Rosaleen (3 September 2004). "Poison campaigner fined after using kiwi in stunt". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ↑ Robertson, HA; et al. (1999). "Survival of brown kiwi exposed to 1080 poison used for control of brushtail possums in Northland, New Zealand".

- ↑ JA McLennan; et al. (1996), Role of predation in the decline of kiwi, Apteryx spp., in New Zealand (PDF)

- ↑ "Threats to Kiwi", Whakatane Kiwi Trust

- ↑ "Kiwi and people: early history", Te Ara, NZ: The Government

- ↑ New Zealand Embassy and Smithsonian National Zoo host handover ceremony to return kiwi feathers to New Zealand, New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade

- ↑ http://kiwison.synthasite.com/relationship-with-humans.php

- ↑ "Captive management plan for kiwi" (PDF). New Zealand Department of Conservation. June 2004. p. 10. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- ↑ Fowler, Murray E; Miller, R Eric (2007), Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine Current Therapy, Elsevier Health Sciences, p. 215

- ↑ Gibson, Eloise (29 April 2010). "Shy envoys off on their OE". New Zealand Herald. p. a4.

- ↑ "Kiwi Fun Facts". Smithsonian's National Zoo. 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ↑ "A kiwi country", Te Ara

- ↑ "The Kiwi". About New Zealand. NZ Search. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ↑ "Kiwi falls after Wheeler talks down intervention, QE". The National Business Review. NZ. 27 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

Further reading

- Burbidge, M.L., Colbourne, R.M., Robertson, H.A., and Baker, A.J. (2003). Molecular and other biological evidence supports the recognition of at least three species of brown kiwi. Conservation Genetics, 4(2):167–77

- Cooper, Alan et al. (2001). Complete mitochondrial genome sequences of two extinct moas clarify ratite evolution. Nature, 409: 704–07.

- SavetheKiwi.org "Producing an Egg". Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- "Kiwi (Apteryx spp.) recovery plan 2008–2018. (Threatened Species Recovery Plan 60)" (PDF). Wellington, NZ: Department of Conservation. 2008. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- Le Duc, D., G. Renaud, A. Krishnan, M.S. Almen, L. Huynen, S. J. Prohaska, M. Ongyerth, B. D. Bitarello, H. B. Schioth, M. Hofreiter, et al. 2015. Kiwi genome provides insights into the evolution of a nocturnal lifestyle. Genome Biology 16:147-162.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apterygidae. |

| Look up kiwi in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Apteryx. |

- "Great Spotted Kiwi", Species: birds, ARKive.

- "Land birds: Kiwi", Native animals: birds, NZ: Department of Conservation.

- Kiwi recovery, NZ: BNZ Save The Kiwi Trust.

- Kiwi, TerraNature.

- How the Kiwi Lost his Wings (Maori legend), Kiwi newz.

- "Kiwi", Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, NZ: The Government.

- "North Island Brown Kiwi feeding in the wild", YouTube (daylight video), Google.

- Pests & threats, Taranaki Kiwi Trust.

- "Case studies on 1080: the facts", 1080 and kiwi, NZ: 1080 facts.