Antiproton

|

The quark structure of the antiproton. | |

| Classification | Antibaryon |

|---|---|

| Composition | 2 up antiquarks, 1 down antiquark |

| Statistics | Fermionic |

| Interactions | Strong, Weak, Electromagnetic, Gravity |

| Status | Discovered |

| Symbol |

p |

| Particle | Proton |

| Discovered | Emilio Segrè & Owen Chamberlain (1955) |

| Mass | 938.2720813(58) MeV/c2 [1] |

| Electric charge | −1 e |

| Spin | 1⁄2 |

| Isospin | -1⁄2 |

| Antimatter |

|---|

|

|

Bodies |

The antiproton,

p

, (pronounced p-bar) is the antiparticle of the proton. Antiprotons are stable, but they are typically short-lived, since any collision with a proton will cause both particles to be annihilated in a burst of energy.

The existence of the antiproton with −1 electric charge, opposite to the +1 electric charge of the proton, was predicted by Paul Dirac in his 1933 Nobel Prize lecture.[2] Dirac received the Nobel Prize for his previous 1928 publication of his Dirac Equation that predicted the existence of positive and negative solutions to the Energy Equation () of Einstein and the existence of the positron, the antimatter analog to the electron, with positive charge and opposite spin.

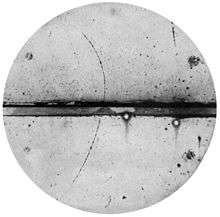

The antiproton was first experimentally confirmed in 1955 at the Bevatron particle accelerator by University of California, Berkeley physicists Emilio Segrè and Owen Chamberlain, for which they were awarded the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physics. In terms of valence quarks, an antiproton consists of two up antiquarks and one down antiquark (

u

u

d

). The properties of the antiproton that have been measured all match the corresponding properties of the proton, with the exception that the antiproton has electric charge and magnetic moment that are the opposites of those in the proton. The questions of how matter is different from antimatter, and the relevance of antimatter in explaining how our universe survived the Big Bang, remain open problems—open, in part, due to the relative dearth of antimatter in today's universe.

Occurrence in nature

Antiprotons have been detected in cosmic rays for over 25 years, first by balloon-borne experiments and more recently by satellite-based detectors. The standard picture for their presence in cosmic rays is that they are produced in collisions of cosmic ray protons with nuclei in the interstellar medium, via the reaction, where A represents a nucleus:

p

+ A →

p

+

p

+

p

+ A

The secondary antiprotons (

p

) then propagate through the galaxy, confined by the galactic magnetic fields. Their energy spectrum is modified by collisions with other atoms in the interstellar medium, and antiprotons can also be lost by "leaking out" of the galaxy.

The antiproton cosmic ray energy spectrum is now measured reliably and is consistent with this standard picture of antiproton production by cosmic ray collisions.[3] This sets upper limits on the number of antiprotons that could be produced in exotic ways, such as from annihilation of supersymmetric dark matter particles in the galaxy or from the evaporation of primordial black holes. This also provides a lower limit on the antiproton lifetime of about 1-10 million years. Since the galactic storage time of antiprotons is about 10 million years, an intrinsic decay lifetime would modify the galactic residence time and distort the spectrum of cosmic ray antiprotons. This is significantly more stringent than the best laboratory measurements of the antiproton lifetime:

- LEAR collaboration at CERN: 0.08 years

- Antihydrogen Penning trap of Gabrielse et al.: 0.28 years[4]

- APEX collaboration at Fermilab: 50000 years for

p

→

μ−

+ anything - APEX collaboration at Fermilab: 300000 years for

p

→

e−

+

γ

The magnitude of properties of the antiproton are predicted by CPT symmetry to be exactly related to those of the proton. In particular, CPT symmetry predicts the mass and lifetime of the antiproton to be the same as those of the proton, and the electric charge and magnetic moment of the antiproton to be opposite in sign and equal in magnitude to those of the proton. CPT symmetry is a basic consequence of quantum field theory and no violations of it have ever been detected.

List of recent antiproton cosmic ray detection experiments

- BESS: balloon-borne experiment, flown in 1993, 1995, 1997, 2000, 2002, 2004 (Polar-I) and 2007 (Polar-II).

- CAPRICE: balloon-borne experiment, flown in 1994[5] and 1998.

- HEAT: balloon-borne experiment, flown in 2000.

- AMS: space-based experiment, prototype flown on the space shuttle in 1998, intended for the International Space Station, launched May 2011.

- PAMELA: satellite experiment to detect cosmic rays and antimatter from space, launched June 2006. Recent report discovered 28 antiprotons in the South Atlantic Anomaly.[6]

Modern experiments and applications

Antiprotons are routinely produced at Fermilab for collider physics operations in the Tevatron, where they are collided with protons. The use of antiprotons allows for a higher average energy of collisions between quarks and antiquarks than would be possible in proton-proton collisions. This is because the valence quarks in the proton, and the valence antiquarks in the antiproton, tend to carry the largest fraction of the proton or antiproton's momentum.

Their formation requires energy equivalent to a temperature of 10 trillion K (1013 K) and this does not tend to happen naturally. However, at CERN, protons are accelerated in the Proton Synchrotron to an energy of 26 GeV, and then smashed into an iridium rod. The protons bounce off the iridium nuclei with enough energy for matter to be created. A range of particles and antiparticles are formed, and the antiprotons are separated off using magnets in vacuum.

In July 2011, the ASACUSA experiment at CERN determined the mass of the antiproton to be 1836.1526736(23) times more massive than an electron.[8] This is the same as the mass of a proton, within the level of certainty of the experiment.

Antiprotons have been shown within laboratory experiments to have the potential to treat certain cancers, in a similar method currently used for ion (proton) therapy.[9] The primary difference between antiproton therapy and proton therapy is that following ion energy deposition the antiproton annihilates depositing additional energy in the cancerous region.

See also

- Antimatter

- Antineutron

- Positron

- Antihydrogen

- Antiprotonic helium

- List of particles

- Recycling antimatter

References

- ↑ Mohr, P.J.; Taylor, B.N. and Newell, D.B. (2015), "The 2014 CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants", National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, US.

- ↑ Dirac, Paul A. M. (1933). "Theory of electrons and positrons" (PDF)

- ↑ Kennedy, Dallas C. (2000). "Cosmic Ray Antiprotons". Proc. SPIE. Gamma-Ray and Cosmic-Ray Detectors, Techniques, and Missions. 2806: 113. arXiv:astro-ph/0003485

. doi:10.1117/12.253971.

. doi:10.1117/12.253971. - ↑ Caso, C.; et al. (1998). "Particle Data Group" (PDF). European Physical Journal C. 3: 613. Bibcode:1998EPJC....3....1P. doi:10.1007/s10052-998-0104-x.

- ↑ Caprice Experiment

- ↑ Adriani, O.; Barbarino, G. C.; Bazilevskaya, G. A.; Bellotti, R.; Boezio, M.; Bogomolov, E. A.; Bongi, M.; Bonvicini, V.; Borisov, S.; Bottai, S.; Bruno, A.; Cafagna, F.; Campana, D.; Carbone, R.; Carlson, P.; Casolino, M.; Castellini, G.; Consiglio, L.; De Pascale, M. P.; De Santis, C.; De Simone, N.; Di Felice, V.; Galper, A. M.; Gillard, W.; Grishantseva, L.; Jerse, G.; Karelin, A. V.; Kheymits, M. D.; Koldashov, S. V.; et al. (2011). "The Discovery of Geomagnetically Trapped Cosmic-Ray Antiprotons". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 737 (2): L29. arXiv:1107.4882v1

. Bibcode:2011ApJ...737L..29A. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/737/2/L29.

. Bibcode:2011ApJ...737L..29A. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/737/2/L29. - ↑ Nagaslaev, V. (17 May 2007). Antiproton Production at Fermilab (PDF). Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ Hori, M.; Sótér, Anna; Barna, Daniel; Dax, Andreas; Hayano, Ryugo; Friedreich, Susanne; Juhász, Bertalan; Pask, Thomas; et al. (2011). "Two-photon laser spectroscopy of antiprotonic helium and the antiproton-to-electron mass ratio". Nature. 475 (7357): 484–8. doi:10.1038/nature10260. PMID 21796208.

- ↑ "Antiproton portable traps and medical applications" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-22.