Amhara people

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 26,867,817[1]:84[2] | |

| 195,260 [3] | |

| 135,500 [4] | |

| 103,000[5] | |

| 88,000 [6] | |

| 18,020 [7] [8] | |

| 12,490 [9] | |

| 11,000 [10] | |

| 10,000 [11] | |

| 8,620 [12] | |

| 6,500[13] | |

| 4,515 [14] | |

| 4,500 [15] | |

| 2,100 [16] | |

| 1,200 [17] | |

| 1,100 [18] | |

| 1,100 [19] | |

| 1,000 [20] | |

| 800 [21] | |

| Languages | |

| Amharic | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity 91.2% (Ethiopian Orthodox) • Islam (Sunni) • Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tigrayans • Tigrinyas • Tigre • Agaw • Saho • Somali • Beja • Gurage • Jeberti • Oromo • Afar[22] | |

|

| |

''This article is about the Amhara people. For their religion, see Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

The Amhara (Amharic: አማራ?, Āmara;[23] Ge'ez: አምሐራ, ʾÄməḥära) are an ethnic group inhabiting the northern and central highlands of Ethiopia, particularly the Amhara Region.[1]:90 and a significant population also live across western countries, in particular United States with 195,260 [24] and 135,500 [25] in Israel . [26] According to the 2007 national census, they numbered 19,867,817 individuals, comprising 27.12% of the country's population.[27][1]:84 The Amhara are one of the Abyssinian peoples. They speak Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia. Amharic is an Afro-Asiatic language of the Semitic branch.

Etymology

The present name for the Amharic language and its speakers comes from the medieval province of Amhara. The latter enclave was located around Lake Tana at the headwaters of the Blue Nile, and included a slightly larger area than Ethiopia's present-day Amhara Region.

The further derivation of the name is debated. Some trace it to amari ("pleasing; beautiful; gracious") or mehare ("gracious"). The Ethiopian historian Getachew Mekonnen Hasen traces it to an ethnic name related to the Himyarites of ancient Yemen.[28] Still others say that it derives from Ge'ez ዓም (ʿam, "people") and ሓራ (h.ara, "free" or "soldier"), although this has been dismissed by scholars such as Donald Levine as a folk etymology.[29]

History

Certain Semitic-speaking peoples, notably the Habesha, built the Kingdom of Aksum around two millennia ago, and this expanded to contain what is now Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, and at times, portions of Yemen and Sudan.

The region now known as "Amhara" in the feudal era was composed of several provinces with greater or less autonomy, which included Gondar, Gojjam, Wollo (Bete Amhara) and Shewa. The traditional homeland of the Amhara people is the central highland plateau of Ethiopia. For over two thousand years they have inhabited this region. Walled by high mountains and cleaved by great gorges, the ancient realm of Abyssinia has been relatively isolated from the influences of the rest of the world. The region is situated at altitudes ranging from roughly 7,000 to 14,000 feet (2,100 to 4,300 meters), and at a 9 o to 14 o latitude north of the equator. The rich volcanic soil combines with a generous rainfall and cool, brisk climate to offer the Amhara a stable agricultural and pastoral existence. However, because the Amhara were an expansionist, militaristic people who ruled their country through a line of emperors, the Amhara people can now be found all over Ethiopia.

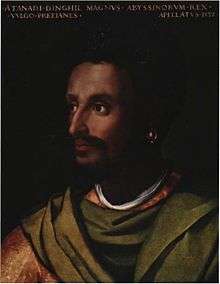

Following the end of the ruling Agaw Zagwe dynasty, the Solomonic dynasty governed the Ethiopian Empire for many centuries from the 1270 AD onwards. In the early 15th century, Abyssinia sought to make diplomatic contact with European kingdoms for the first time since Aksumite times. A letter from King Henry IV of England to the Emperor of Abyssinia survives.[30] In 1428, the Emperor Yeshaq sent two emissaries to Alfonso V of Aragon, who sent return emissaries who failed to complete the return trip.[31] The first continuous relations with a European country began in 1508 with Portugal under Emperor Lebna Dengel, who had just inherited the throne from his father.[32]

This proved to be an important development, for when the Empire was subjected to the attacks of the Adal Sultanate General and Imam, Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (called "Grañ", or "the Left-handed"), Portugal assisted the Ethiopian emperor by sending weapons and four hundred men, who helped his son Gelawdewos defeat Ahmad and re-establish his rule.[33] This Ethiopian–Adal War was also one of the first proxy wars in the region as the Ottoman Empire and Portugal took sides in the conflict.

The Amhara have contributed many rulers over the centuries, including Haile Selassie, who was of mixed heritage.[34] Haile Selassie's mother was paternally of Oromo descent and maternally of Gurage heritage, while his father was paternally Oromo and maternally Amhara. He consequently would have been considered Oromo in a patrilineal society, and would have been viewed as Gurage in a matrilineal one. However, in the main, Haile Selassie was regarded as Amhara, his paternal grandmother's royal lineage, through which he was able to ascend to the Imperial throne.[35]

Social stratification

Within traditional Amharic society and that of other local Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations, there were four basic strata. According to the Ethiopianist Donald Levine, these consisted of high-ranking clans, low-ranking clans, caste groups (artisans), and slaves.[36] Slaves were at the bottom of the hierarchy, and were primarily drawn from the pagan Nilotic Shanqella groups. Also known as the barya (meaning "slave" in Amharic), they were captured during slave raids in Ethiopia's southern hinterland. War captives were another source of slaves, but the perception, treatment and duties of these prisoners was markedly different.[37] Although most slaves were Shanqella, any more powerful group was liable to consign to slavery weaker members of other communities or even from its own tribe, including the Amhara.[36]

The separate, Amhara caste system, ranked higher than slaves, consisted of: (1) endogamy, (2) hierarchical status, (3) restraints on commensality, (4) pollution concepts, (5) each caste has had a traditional occupation, and (6) inherited caste membership.[36] Scholars accept that there has been a rigid, endogamous and occupationally closed social stratification among Amhara and other Afro-Asiatic-speaking Ethiopian ethnic groups. However, some label it as an economically closed, endogamous class system or as occupational minorities,[38] whereas others such as the historian David Todd assert that this system can be unequivocally labelled as caste-based.[39][40][41]

Language

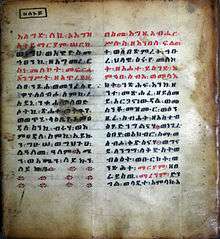

The Amhara speak the Amharic language (also known as Amarigna or Amarinya) as a mother tongue. It belongs to the Semitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family.[42]

Amharic is the working language of the federal authorities of Ethiopia government. It was for some time also the language of primary school instruction, but has been replaced in many areas by regional languages such as Oromifa and Tigrinya. Never the less Amharic is still widely used as the working language of Amhara Region, Benishangul-Gumuz Region, Gambela Region and Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region .[43] The Amharic language is transcribed using the Ethiopic or Ge'ez script (Fidäl), an abugida. The Amharic language is the official language of Ethiopia.

Religion

The predominant religion of the Amhara for centuries has been Christianity, with the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church playing a central role in the culture of the country. According to the 1994 census, 81.5% of the population of the Amhara Region (which is 91.2% Amhara) were Ethiopian Orthodox; 18.1% were Muslim, and 0.1% were Protestant ("P'ent'ay").[44] The Ethiopian Orthodox Church maintains close links with the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. Easter and Epiphany are the most important celebrations, marked with services, feasting and dancing. There are also many feast days throughout the year, when only vegetables or fish may be eaten.

Marriages are often arranged, with men marrying in their late teens or early twenties.[45] Traditionally, girls were married as young as 14, but in the 20th century, the minimum age was raised to 18, and this was enforced by the Imperial government. Civil marriages are common, as well as churches. After a church wedding, divorce is frowned upon.[45] Each family hosts a separate wedding feast after the wedding.

Upon childbirth, a priest will visit the family to bless the infant. The mother and child remain in the house for 40 days after birth for physical and emotional strength. The infant will be taken to the church for baptism at 40 days (for boys) or 80 days (for girls).

Culture

Art

Ethiopian art is typified by religious paintings. One of the most notable features of these is the large eyes of the subjects, who are usually biblical figures. Amhara painting is a dominant art form in Ethiopia. It is usually oil on canvas or hide, and it normally involves religious themes. Ethiopian paintings from the Middle Ages are known by art historians from Europe and America as distinct treasures of human civilization. The Amhara are also weavers of beautiful patterns embellished with embroidery. They are fine gold- and silversmiths and produce delicate works of filigree jewelry and religious emblems.

Agriculture

About 90% of the Amhara are rural and make their living through farming, mostly in the Ethiopian highlands. Prior to the 1974 Ethiopian Revolution, absentee landlords maintained strict control over their sharecropping tenants, often allowing them to accumulate crippling debt. After 1974, the landlords were replaced by local government officials, who play a similar role.

Barley, corn, millet, wheat, sorghum, and teff, along with beans, peppers, chickpeas, and other vegetables, are the most important crops. In the highlands one crop per year is normal, while in the lowlands two are possible. Cattle, sheep, and goats are also raised.

Cuisine

The Amhara people's cuisine and that of Ethiopian cuisine in general consists of various vegetable or meat side dishes and entrées, usually a wat, or thick stew, served atop injera, a large sourdough flatbread made of teff flour. Kitfo being originated from Gurage is one of the widely accepted and favorite food in Amhara and all over Ethiopia.

Tihlo prepared from roasted barley flour is very popular in Amhara, Agame, and Awlaelo (Tigrai). Traditional Ethiopian cuisine employs no pork or shellfish of any kind, as they are forbidden in the Islamic, Jewish, and Ethiopian Orthodox Christian faiths. It is also very common to eat from the same dish in the center of the table with a group of people.

Validity of ethnic group status [46]

Up until the last quarter of the 20th century, "Amhara" was only used (in the form amariñña) to refer to Amharic, the language, or the medieval province located in Wollo (modern Amhara Region). Still today, most people labeled by outsiders as "Amhara", refer to themselves simply as "Ethiopian", or to their province (e.g. Gojjamé from the province Gojjam). According to Ethiopian ethnographer Donald Levine, "Amharic-speaking Shewans consider themselves closer to non-Amharic-speaking Shewans than to Amharic-speakers from distant regions like Gondar."[47] Amharic-speakers tend to be a "supra-ethnic group" composed of "fused stock".[48] Takkele Taddese describes the Amhara as follows:

The Amhara can thus be said to exist in the sense of being a fused stock, a supra-ethnically conscious ethnic Ethiopian serving as the pot in which all the other ethnic groups are supposed to melt. The language, Amharic, serves as the center of this melting process although it is difficult to conceive of a language without the existence of a corresponding distinct ethnic group speaking it as a mother tongue. The Amhara does not exist, however, in the sense of being a distinct ethnic group promoting its own interests and advancing the Herrenvolk philosophy and ideology as has been presented by the elite politicians. The basic principle of those who affirm the existence of the Amhara as a distinct ethnic group, therefore, is that the Amhara should be dislodged from the position of supremacy and each ethnic group should be freed from Amhara domination to have equal status with everybody else. This sense of Amhara existence can be viewed as a myth.[48]

Notable Amharas

- Yekuno Amlak,[49] founder of the Solomonic Dynasty

- Amda Seyon I,[50] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Newaya Krestos,[51][52] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Newaya Maryam,[53] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Dawit I,[50] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Yeshaq I,[54] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Zara Yaqob,[55] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Baeda Maryam I,[50] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Eskender,[56] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Na'od,[52] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Dawit II,[52][57] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Gelawdewos,[50] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Menas of Ethiopia,[50] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Sarsa Dengel,[58] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Yaqob,[59] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Susenyos I, Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire[60]

- Fasilides,[50] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Iyasu I,[50] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Dawit III,[61] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Bakaffa,[52] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Iyasu II,[52] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

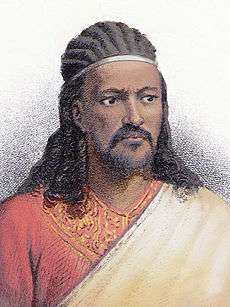

- Tewodros II,[62] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Menelik II,[63] Emperor of the Ethiopian Empire

- Asrat Woldeyes,[64] Surgeon

- Belay Zeleke,[65] patriot

- Afewerk Tekle, Honorable Laureate Maitre Artiste

- Getatchew Haile,[66] philologist

- Haile Gerima, Award winning writer, producer & director.

- Abune Petros,[50] patriot

- Aba Gorgorios,[67] Catholic priest

- Aklilu Habte-Wold, Prime Minister

- Wolde Giorgis Wolde Yohannes, Minister of the pen

- Heruy Wolde Selassie, Foreign Minister

- Seifu Mikael, diplomat, governor

- Workneh Eshete, surgeon and diplomat

- Haddis Alemayehu, Foreign Minister and Novelist

- Asrat Woldeyes, MD, Ethiopian surgeon and politician

- The Weeknd, Ethiopian-Canadian R&B artist

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopia. "Table 5: Population Size of Regions by Nations/Nationalities (Ethnic Group) and Place of Residence: 2007" (PDF). Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results. United Nations Population Fund. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ Abebe, Semahagn Gashu. Federalism Studies : The Last Post-Cold War Socialist Federation : Ethnicity, Ideology and Democracy in Ethiopia, Pv. Farnham, GB: Routledge, 2014 (p.75). ProQuest ebrary. Web. 29 November 2016. Copyright © 2014. Routledge. All rights reserved.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau 2009-2013, T Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2009-2013, , USCB, 30 Novemeber 2016, <http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html>.

- ↑ The Situation of Ethiopian Jews in Israel | Jewish Virtual Library. 2016. The Situation of Ethiopian Jews in Israel | Jewish Virtual Library. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/ejdesc.html. [Accessed 30 November 2016].

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Statistics Canada, 2011 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-314-XCB2011032

- ↑ Anon, 2016. 2011 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations | Detailed Mother Tongue (232), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population Excluding Institutional Residents of Canada and Forward Sortation Areas, 2011 Census. [online] Www12.statcan.gc.ca. Available at: <http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/tbt-tt/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=103001&PRID=10&PTYPE=101955&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2011&THEME=90&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=> [Accessed 2 Dec. 2016].

- ↑ Nathalie Schlenzka. 2009. The Ethiopian Diaspora in Germany Its Contribution to Development in Ethiopia. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.giz.de/fachexpertise/downloads/gtz2009-en-ethiopian-diaspora.pdf. [Accessed 3 December 2016].

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ pp, 25 (2015) United Kingdom. Available at: https://www.ethnologue.com/country/GB (Accessed: 30 November 2016).

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics 2014, The People of Australia Statistics from the 2011 Census, Cat. no. 2901.0, ABS, 30 Novemeber 2016, <https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf>.

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Project, J. (2016) Amhara, Ethiopian in New Zealand. Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/10294/NZ (Accessed: 30 November 2016).

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Joshua Project. 2016. Language - Amharic :: Joshua Project . [ONLINE] Available at: https://joshuaproject.net/languages/amh?limit=500. [Accessed 03 December 2016].

- ↑ Joireman, Sandra F. (1997). Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development. Universal-Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 1581120001.

The Horn of Africa encompasses the countries of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia. These countries share similar peoples, languages, and geographical endowments.

- ↑ Following the BGN/PCGN romanization employed for Amharic geographic names in British and American English.

- ↑ http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html

- ↑ The Situation of Ethiopian Jews in Israel | Jewish Virtual Library. 2016. The Situation of Ethiopian Jews in Israel | Jewish Virtual Library. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/ejdesc.html. [Accessed 30 November 2016].

- ↑ http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html

- ↑ Abebe, Semahagn Gashu. Federalism Studies : The Last Post-Cold War Socialist Federation : Ethnicity, Ideology and Democracy in Ethiopia. Farnham, GB: Routledge, 2014, (p.75). ProQuest ebrary. Web. 29 November 2016. Copyright © 2014. Routledge. All rights reserved.

- ↑ Getachew Mekonnen Hasen. Wollo, Yager Dibab, p. 11. Nigd Matemiya Bet (Addis Ababa), 1992.

- ↑ Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. "Amhara" in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, p. 230. Harrassowitz Verlag (Wiesbaden), 2003.

- ↑ Ian Mortimer, The Fears of Henry IV (2007), p.111 ISBN 1-84413-529-2

- ↑ Beshah, pp. 13–4.

- ↑ Beshah, p. 25.

- ↑ Beshah, pp. 45–52.

- ↑ Kjetil Tronvoll, Ethiopia, a new start?, (Minority Rights Group: 2000)

- ↑ Peter Woodward, Conflict and peace in the Horn of Africa: federalism and its alternatives, (Dartmouth Pub. Co.: 1994), p.29.

- 1 2 3 Donald N. Levine (2014). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

- ↑ Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769-1855. Praeger. p. 57.

- ↑ Teshale Tibebu (1995). The Making of Modern Ethiopia: 1896-1974. The Red Sea Press. pp. 67–70. ISBN 978-1-56902-001-2.

- ↑ Todd, David M. (1977). "Caste in Africa?". Africa. Cambridge University Press. 47 (04): 398–412. doi:10.2307/1158345.

Dave Todd (1978), "The origins of outcastes in Ethiopia: reflections on an evolutionary theory", Abbay, Volume 9, pages 145-158 - ↑ Lewis, Herbert S. (2006). "Historical problems in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Wiley-Blackwell. 96 (2): 504–511. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb50145.x.

- ↑ Niall Finneran (2013). The Archaeology of Ethiopia. Routledge. pp. 14–15. ISBN 1-136-75552-7., Quote: "Ethiopia has, until fairly recently, been a rigid feudal society with finely grained perceptions of class and caste".

- ↑ "Amharic language". Ethnologue. 1999-02-19. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ Danver, Steven Laurence. Native Peoples Of The World. 1st ed. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, an imprint of M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2013. Print.

- ↑ "FDRE States: Basic Information – Amhara". Population. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2006.

- 1 2 "African Marriage ritual". Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ↑ ⭐Ethnic group statistics A guide for the collection and classification of ethnicity data. 2016. ⭐Ethnic group statistics A guide for the collection and classification of ethnicity data. [ONLINE] Available at: http://docplayer.net/254484-Ethnic-group-statistics-a-guide-for-the-collection-and-classification-of-ethnicity-data.html. [Accessed 02 December 2016].

- ↑ Donald N. Levine "Amhara," in von Uhlig, Siegbert, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica:A-C, 2003, p.231.

- 1 2 Takkele Taddese "Do the Amhara Exist as a Distinct Ethnic Group?" in Marcus, Harold G., ed., Papers of the 12th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, 1994, pp.168–186.

- ↑ Shinn, David; Ofcansky, Thomas (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Amhara Contributions to Ethiopian Civilization". Ethiopian Review. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ James Bruce, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1805 edition), vol. 3 pp. 93f

- 1 2 3 4 5 http://www.ethiopianreview.com/index/382

- ↑ J. Spencer Trimingham, Islam in Ethiopia (Oxford: Geoffrey Cumberlege for the University Press, 1952), p. 74.

- ↑ Kessle, David (1996). The Falashas: A Short History of the Ethiopian Jews. p. 94.

- ↑ Shinn, David; Ofcansky, Thomas (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. p. 6.

- ↑ Hubert Jules Deschamps, (sous la direction). Histoire générale de l'Afrique noire de Madagascar et de ses archipels Tome I : Des origines à 1800. p. 406 P.U.F Paris (1970)

- ↑ http://epicworldhistory.blogspot.nl/2012/06/lebna-dengel-ethiopian-ruler.html

- ↑ Gordon, Howard (2011). Be Not Thy Father's Son. p. 128.

- ↑ Stewart, John (2006). African States and Rulers. p. 93.

- ↑ Vitae Sanctorum Indigenarum: I Acta S. Walatta Petros, Ii Miracula S. Zara-Baruk, edited by Carlo Conti Rossini and C. Jaeger Louvain: L. Durbecq, 1954, pg. 62.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=TzOxCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA67&lpg=PA67&dq=iyasu+ii+brother+dawit+iii&source=bl&ots=0VdnqqRLl5&sig=6mGTB4qKBRyXjGcBIwoQV_g6-VE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiZwcaf-d_PAhWBLsAKHR6FDysQ6AEIWzAI#v=onepage&q=iyasu%20ii%20brother%20dawit%20iii&f=false

- ↑ Young, John (1997). Peasant Revolution in Ethiopia: The Tigray People's Liberation Front, 1975-1991. p. 44.

- ↑ Foster, Mary; Rubinstein, Robert (1986). Peace and War: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. p. 137.

- ↑ "Asrat Woldeyes". the Guardian. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ Administrator. "Belay Zeleke". Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Senamirmir Projects: Interview with Dr. Getatchew Haile". Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ Belcher, Laura (2012). Abyssinia's Samuel Johnson: Ethiopian Thought in the Making of an English Author. p. 114.

Further reading

- Wolf Leslau and Thomas L. Kane (collected and edited), Amharic Cultural Reader. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2001. ISBN 3-447-04496-9.

- Donald N. Levine, Wax & Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopian Culture (Chicago: University Press, 1972) ISBN 0-226-45763-X

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amhara. |

- Lemma, Marcos (MD, PhD). "Who ruled Ethiopia? The myth of 'Amara domination'". Ethiomedia.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2005. Retrieved 28 February 2005.

- People of Africa, Amhara Culture and History