Alfred Flechtheim

| Alfred Flechtheim | |

|---|---|

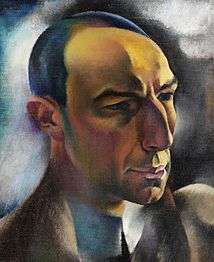

Alfred Flechtheim, 1910 | |

| Born |

April 1, 1878 Münster, Westphalia, German Empire |

| Died |

March 9, 1937 (aged 58) London, England |

| Nationality | Germany |

| Occupation | Art dealer |

| Spouse(s) | Betty Goldschmidt (m. 1910) |

Alfred Flechtheim (April 1, 1878 – March 9, 1937) was a German art dealer, art collector, journalist and publisher.

Early Years

Flechtheim was born into a Jewish merchant family; his father, Emil Flechtheim, was a grain dealer. Alfred became a partner in his father's company after business internships in London and Paris.[1]

Art Dealer

Flechtheim appeared in the art world shortly after 1900, with a collection of paintings by Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne; French Avant garde early works of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and André Derain; paintings of Wassily Kandinsky, Maurice de Vlaminck, Alexej von Jawlensky, Gabriele Münter, and the Rhein Expressionists Heinrich Campendonk, August Macke, Heinrich Nauen, and Paul Adolf Seehaus. Flechtheim opened his first gallery in Düsseldorf in 1913, followed by galleries in Berlin, Frankfurt, Cologne, and Vienna.[2]

Later career

Flechtheim served in the German Army during World War I, but not at the front. His art business collapsed during the war but he re-opened in Düsseldorf in 1919.[3] In 1921 he founded Der Querschnitt (the Cross Section), a cultural magazine. Legendary, glamorous parties in Flechtheim's gallery overflowed with the glitterati of the new Berlin: movie stars, titans of finance, prizefighters and artists of every stripe.[4]

Flechtheim, Nazis and Aryanization

As Hitler rose to power in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Flechtheim became a bête noire because of the art he espoused and championed. In 1933, Sturmabteilung men broke up an auction of Flechtheim's paintings. In March 1933, an art dealer named Alexander Vömel, a member of the SA or Brown Shirts, confiscated Flechtheim’s Düsseldorf gallery.[5] The Nazis aryanized Flechtheim's gallery, as they would many other Jewish businesses,.[6] After the war, former party member Vömel said he didn't even remember who Flechtheim was. Flechtheim's former assistant, Curt Valentin, left the Flechtheim Gallery in 1934 and began working in the Berlin gallery of Karl Buchholz, who was not Jewish.[7] The Nazis seized and sold off Flechtheim's private collection, as well as the contents of his gallery.

Emigration and Death

Six months after the Nazis came to power in 1933, Flechtheim, penniless, fled to Paris, and tried to find work with his former business partner, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. Flechtheim subsequently organized exhibits in London of the paintings of exiled German artists. On August 8, 1935, Flechtheim wrote Alfred Barr of the MOMA a letter informing him, “I lost all my money and all my pictures.” By November 1936, Flechtheim's former gallery assistant, Curt Valentin, had made a deal with the Nazis that would allow him to emigrate to New York and to sell “degenerate art” to help fund the Nazi war effort.[8] In January 1937, with financing from Buchholz, Valentin left for New York and set up the Karl Buchholz Gallery at 3 West 46th Street which was later accused of serving as a conduit for bringing Nazi looted art, including paintings that had been seized from Flechtheim, into America.[9] In March 1937 in London, Flechtheim slipped on a patch of ice, was taken to a hospital, punctured his leg on a rusty nail in his hospital bed, developed septicemia leading to amputation of his leg, and died. The Galerie Alfred Flechtheim GmbH disappeared in its entirety on 27 March 1937[10]

Personal life

Flechtheim married Betty Goldschmidt, a wealthy Dortmund merchant's daughter. On a honeymoon trip to Paris, Flechtheim invested Betty's dowry in cubist art, to the horror of his inlaws. The marriage was childless. Betty Flechtheim was with her husband in London during his final days. Then she returned to Berlin. In 1941, when she was ordered to report for deportation to Minsk, she ingested a lethal dose of Veronal. The Gestapo seized her art collection.[11] Professor Ossip K. Flechtheim, who in mid-1940s coined the term "Futurology", and later became a director of Otto-Suhr-Institut in West Berlin, was Alfred Flechtheim's nephew.

Recovery of artworks

Flechtheim's heirs are attempting to recover artworks stolen from Flechtheim. These works reside in German museums and the Museum of Modern Art.[12]

Gallery

-

Portrait of Alfred Flechtheim by Hanns Bolz (1885-1918)

-

Alfred Flechtheim dressed as a toreador by Jules Pascin, 1927

-

As painted in 1913 by Swedish painter Nils Dardel (1888-1943)

References

- ↑ Gee, Malcolm (1981). Dealers, Critics, and Collectors of Modern Painting: Aspects of the Parisian Art Market between 1910 and 1930. London: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-3931-9.

- ↑ Sontheimer, Michael (25 June 2012). "Stärker als Spiel, Alkohol und Weiber". Der Spiegel (in German) (26/2012).

- ↑ Malcolm Gee, ‘The Berlin Art World, 1918-1933’ in: Malcolm Gee, Tim Kirk and Jill Steward (eds), The City in central Europe : culture and society from 1800 to the present, Ashgate, 1999.

- ↑ Dascher, Ottfried (2011). "Es ist was Wahnsinniges mit der Kunst": Alfred Flechtheim. Sammler, Kunsthändler und Verleger (in German). Wädenswil: Nimbus. ISBN 978-3-907142-62-2.

- ↑ http://www.artnews.com/2011/11/17/momas-problematic-provenances/

- ↑ Lehrer, Steven (2000). Wannsee House and the Holocaust. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 36–47. ISBN 0-7864-4092-9.

- ↑ http://www.artnews.com/2011/11/17/momas-problematic-provenances/

- ↑ http://www.artnews.com/2011/11/17/momas-problematic-provenances/

- ↑ http://www.artnews.com/2011/11/17/momas-problematic-provenances/

- ↑ http://alfredflechtheim.com/en/alfred-flechtheim/liquidation/

- ↑ Koldehoff, Stefan (30 June 2010). "Mit deutschen Grüßen". Die Welt (in German).

- ↑ Burleigh, Nina. "Haunting MoMA: The Forgotten Story of 'Degenerate' Dealer Alfred Flechtheim". Gallerist New York.

External links

- Alfred Flechtheim: Art Dealer of the AvantGarde

- The Devil and the Art Dealer

- Haunting MoMA: The Forgotten Story of ‘Degenerate’ Dealer Alfred Flechtheim

- Artworks Stolen From Alfred Flechtheim at the MOMA

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alfred Flechtheim. |