Albert Herter

| Albert Herter | |

|---|---|

Albert Herter | |

| Born |

March 2, 1871 New York, New York |

| Died | February 25, 1950 (aged 78) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

Albert Herter (March 2, 1871 – February 15, 1950) was an American painter, illustrator, muralist, and interior designer. He was born in New York City, studied at the Art Students League with James Carroll Beckwith, then in Paris with Jean-Paul Laurens and Fernand Cormon.[1]

He came from an artistic family; his father, Christian Herter (1839–1883), had co-founded Herter Brothers, a prominent New York interior design and furnishings firm. Herter Brothers closed its doors in 1906, and Albert founded Herter Looms in 1909, a tapestry and textile design-and-manufacturing firm that was, in a sense, successor to his father's firm.

Personal

In Paris, he met a fellow American art student, Adele McGinnis. They were married in 1893 and had three children: Everit Albert (1894–1918), Christian Archibald (1895–1966), and Lydia Adele (1898–1951). The couple honeymooned in Japan, then returned to Paris for the first years of their marriage. In 1898 they moved back to the United States and built a Mediterranean-style villa, called "The Creeks", in East Hampton, New York, with a studio for each of them. Herter's mother built a mansion, "El Mirasol," in Santa Barbara, California, where the family spent the winters. Following his mother's death, Herter and his wife renovated the mansion and converted it into a boutique hotel. Son Everit and daughter Lydia also became artists although Everit was killed at age 24 in World War I. Son Christian became a politician, serving as governor of Massachusetts and later U.S. Secretary of State under Dwight D. Eisenhower. Adele Herter is remembered as a painter of still lifes and "Society" portraits.

Paintings

Herter had an extraordinary early career, at age 19 receiving an honorable mention at the Paris Salon (1890, La Femme de Buddha), and winning prizes from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1897 Lippincott Prize, Le Soir), the American Watercolor Society (1899 Evans Prize, The Gift of Roses), and elsewhere. He was awarded medals at the 1895 Atlanta Exposition (1830, The Muse), the 1897 Nashville Exposition (The Muse), the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle (Sorrow), and the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo (Gloria, The Danaides).[1]

- Portrait of Bessie (1892), High Museum of Art.[2]

- The Muse (1894), Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

- Woman with Red Hair (1894), Smithsonian American Art Museum.[3]

- Garden of the Hesperides (c. 1898), private collection.[4]

- Self-Portrait in Costume of Hamlet (c. 1900), Smithsonian American Art Museum.[5]

- Portrait of Courtlandt Palmer (1906), Metropolitan Museum of Art.[6] Palmer (1872–1951), a composer, is shown at the piano.

- Pendant portraits of Mr. & Mrs. Charles W. Harkness (c. 1910-15), Yale University Art Gallery.

- Portrait of a Young Russian Nobleman (c. 1918), Metropolitan Museum of Art.[7]

- Pilgun Yoon as “Aladdin” (c. 1923), Brooklyn Museum.[8]

- The Bouvier Twins (1926), private collection.[9] A double portrait of Maude and Michelle Bouvier, aunts of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis.

Illustrations

He painted covers for the Ladies' Home Journal and other magazines, and illustrated a number of books.[10] He created several World War I posters.[11]

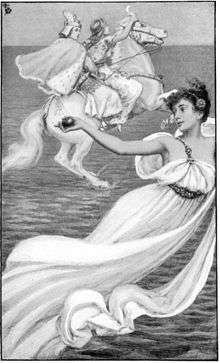

-

Frontispiece—Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic, 1899.

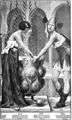

-

Pryderi and Rhiannon from Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic.

-

Merlin and Vivian from Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic.

-

King Arthur from Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic.

-

Maiden of the brazen door from Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic.

-

Demon hand from Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic.

-

1917 poster for the Red Cross.

-

1918 poster for the YMCA.

Murals

In 1909, Herter was commissioned by the Daughters of the American Revolution to create what was intended to be the world's largest painted theater curtain, for the Denver Auditorium. The flat curtain was 35 feet (11 m) high and 60 feet (18 m) wide. Its theme was an allegory of the United States Declaration of Independence, and included illustrations of historical figures such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin.

He executed murals for buildings such as the Massachusetts Statehouse, the Wisconsin State Capitol, the Los Angeles Public Library, and the National Academy of Sciences.[1]

His best-known work, Le Départ des poilus, août 1914 (Departure of the Infantrymen, August 1914), is a mural in the Gare de Paris-Est railroad station in Paris.[1] The Herters' elder son, Everit, volunteered to fight in World War I, and was killed in June 1918.[12][13] Herter channeled his grief into this mural, which depicts soldiers leaving for war from that same railroad station. The young man at center with his arms in the air is a portrait of Everit, the woman in white at far left is a portrait of Adele Herter, and the man at far right with the bouquet of flowers is a self-portrait. Herter donated the mural to the People of France in 1926.

- Der Nibelungen (circa 1898) - six murals, music room, Emilie Grigsby House, 67th Street & Park Avenue, New York City:[14] The murals were sold at auction for $2,500 in 1912.[15]

- The Pageant of Nations (1913) - seven murals, The Mural Room, St. Francis Hotel, San Francisco, California. Included a portrait of Gertrude Atherton posing as "California." The Herter murals were taken down and placed in storage in 1971. The Mural Room was demolished during hotel expansion and remade as a larger lobby and front desk area.

- Two murals, Connecticut Supreme Court Building, Hartford. Painted on canvas at Herter's studio at "The Creeks" in East Hampton, New York, then taken to Hartford and affixed to wall and ceiling with white lead.

- An Allegory of Education (1913)

- Fundamental Orders 1638-1639 (1913)

- Four murals, Supreme Court Chamber, Wisconsin State Capitol, Madison:

- Two murals, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C.:

- Le Départ des poilus, août 1914 (Departure of the Infantrymen, August 1914) (1926), Gare de Paris-Est, Paris. Given by Herter to the people of France following World War I.

- Eight murals, Children's Literature Department, Main Branch, Los Angeles Public Library:

- Warner Brothers Hollywood Theatre (1928–30), New York City. This movie palace was converted into the Mark Hellinger Theatre in 1949. In 1989, it became the Times Square Church, which continues to occupy it. Herter's murals have been taken down.

- Library portico, Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, Florida (1939)[27]

- Milestones on the Road to Freedom in Massachusetts (1942) - five mural-sized paintings, House of Representatives, Massachusetts State House, Boston

Tapestries

"Though a painter by profession, Mr. Herter has a keen appreciation of tapestry texture, which he has developed by personal work at the loom. Especially interesting should be the set of 26 panels now on the looms, picturing The Story of New York back to the days when Peter Stuyvesant smoked his long-stemmed pipe and cursed in Dutch."[28]

- The Story of New York (1912) - 28 panels, McAlpin Hotel, New York City.

- The Great Crusade (1920), Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.[29]

Interior design

Herter designed Spanish Colonial Revival interiors for the Loew's Warfield Theater (1923) in San Francisco, including a bullfighting mural above the proscenium. He designed Byzantine Revival interiors for the Martin Beck Theatre (1924) in New York City,[30] which was renamed the Al Hirschfeld Theatre in 2003.

The Creeks

In 1894, as a wedding gift from the groom's mother, Mary Miles Herter, the couple received a 70-acre (280,000 m2) parcel of land between Montauk Highway and Georgica Pond, in East Hampton, Long Island. In 1899, they built "The Creeks," a 40-room, Mediterranean-style villa, designed by architect Grosvenor Atterbury. The estate featured about a mile of waterfront on the tidal estuary. The villa contained "his and hers" artist studios so each would have their own workspace. Adele Herter designed the extensive gardens. In 1912, Albert Herter built a larger studio, a soaring 56-by-35-foot space that doubled as a private theater, "where Enrico Caruso, Isadora Duncan and Anna Pavlova performed."[31]

One of the finest examples of a color plan in our architecture is the country place of Mr. Albert Herter at East Hampton, Long Island. Here is a large, rambling house, built so close to the sea that the blue-green of the water and the clear blue of the sky are deliberately considered as a part of the color plan. Mr. Herter's idea was to get, if possible, the effect of a house in Sicily, and so he built the house of pinkish yellow stucco and gave it a copper roof. The sea winds have softened the texture and deepened the color of the walls to salmon, and the copper roof has been transformed into ever-changing blue-greens that repeat the colors of the sea. In front of the house there are terraces massed with flowers of orange and yellow and red, and back of the house there is a Persian garden built around blue and green Persian tiles, and great blue Italian jars. Here flowers of blue and rose, and the amethyst tones in between, are allowed. Black green trees and shrubs are used everywhere, with the general effect of one of Maxfield Parrish's vivid Oriental gardens.[32]

After his wife Adele's death at "The Creeks" in 1946,[33] Albert Herter moved permanently to California. After his death, his son Christian Herter sold the estate to Alfonso A. Ossorio in 1951. Ossorio used the house as a gallery to display art collections and worked for 20 years in the gardens landscaping with exotic conifer species in groves dotted with his brightly colored found art sculptures. He donated 4 acres (16,000 m2) of "The Creeks" to the Nature Conservancy in 1975. After Ossorio's death in 1990, the property was offered for sale by his partner, dancer Ted Dragon, at the asking price of US$25M.[34] It is now owned by Ronald Perelman.

-

"The Creeks," 1905.

-

View from front door, 1913.

-

Orange & Yellow Garden, 1913. Albert Herter's studio is the building at left.

-

Blue & White Garden, 1913.

-

Terrace, 1913.

-

Boathouse, 1913.

-

Living Room Fireplace, 1917.

El Mirasol

Adele and Albert Herter spent a good deal of their time in California at "El Mirasol", the grand family estate bought in 1904 in Santa Barbara where his mother Mary Miles Herter had entertained friends such as Robert Louis Stevenson's widow Fanny Vandegrift (who later retired to and died at "El Mirasol" in 1914.)[33] The 4.6-acre (19,000 m2) parcel comprising an entire city block contained a prominent mansion surrounded by gardens. Adele and Albert undertook two major decoration efforts at the estate: the first at the mansion's initial outfitting in 1909 which incorporated earlier Herter Brothers furnishings, new Tiffany lamps designed by Albert Herter, original wall hangings and works of art by both Albert and Adele as well as by other California artists.[33] Following the death of Albert's mother in 1913, the estate received a new round of renovation in 1914 with its conversion into "El Mirasol Hotel"; Herter expanded the mansion and added 15 luxurious bungalows around the gardens.[35] The hotel was famed not only for its balanced design and private tranquility but for its wealthy guests including the Vanderbilts, the Rockefellers, the Guggenheims, and the heirs of Charles Crocker, J. P. Morgan and Philip Danforth Armour.[35] In 1920, Herter sold the property to Frederick C. Clift, the hotelier and attorney from the Sierras. After the 1920s, times were hard on the hotel. Under different owners it settled into primarily a retirement home for the wealthy elderly. Herter himself died at "El Mirasol" in 1950.[35]

Two attic fires damaged the west wing of the mansion in 1966. Rather than repairing it, two consecutive owners tried in vain to build high-rise shopping on the lot; the buildings and gardens were bulldozed and cleared but neighbors and a citizen's committee fought successfully against city approval of high-rise plans. The block sat empty for a few years while the Santa Barbara Museum of Art considered building a main gallery there. In December 1975 the parcel was quietly bought by Santa Barbara resident Alice Keck Park who immediately donated it to the city of Santa Barbara to become an urban park in perpetuity: Alice Keck Park Memorial Gardens.[35]

The Gift of Eternal Life

Herter wrote and produced a play called The Gift of Eternal Life, An Indo-Persian Legend. It was performed at the Lobero Theatre in Santa Barbara, March 20–23, 1929. He designed the sets and costumes, and played the part of the King. It was produced through the Drama Branch of the Community Arts Music Association of Santa Barbara. In the playbill, he acknowledged the writings of Lily Adams Beck for inspiring the Orientalist theme and "much of its imagery," and said that he also used several lines written by Rabindranath Tagore and Ananda Coomaraswamy. The cast was made up primarily of locals, although Herter's friend, dancer Ruth St. Denis, played the lead.[36]

Honors

He was elected an associate member of the National Academy of Design in 1906, and became a full Academician in 1943. He was a member of the Society of American Artists, the American Watercolor Society, the New York Water Color Club, the Society of Mural Painters, and the Century Club.[1] He was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor in 1923.[37]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Albert Herter (1871-1950), from AskArt.

- ↑ Portrait of Bessie, from High Museum of Art.

- ↑ Woman with Red Hair, from Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- ↑ Garden of the Hesperides, from Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ Self-Portrait in Costume of Hamlet, from Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- ↑ Portrait of Courtlandt Palmer, from Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Portrait of a Russian Nobleman, from Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Pilgun Yoon as "Aladdin", from Brooklyn Museum.

- ↑ The Bouvier Twins, from ArtNet.

- ↑ Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic (1898).

- ↑ World War I posters by Herter, from Library of Congress.

- ↑ "New York Artist Killed in France," The New York Times, June 28, 1918.

- ↑ HERTER, Everit Albert. Sergeant First Class, U.S. Army, 40th Engineer Regiment. Entered the Service from: New York. Died: June 13, 1918. Buried at: Plot A, Row 13, Grave 59, Aisne-Marne American Cemetery, Belleau, France.

- ↑ The Lost Emilie Grigsby House, from Daytonian in Manhattan.

- ↑ "$193,067 Realized at Grigsby Art Sale," The New York Times, January 28, 1912.

- ↑ Roman Law from Wiki Commons.

- ↑ English Law from Wiki Commons.

- ↑ Local Law from Wiki Commons.

- ↑ The Signing of the Constitution from Wiki Commons.

- ↑ Restoration of the Herter murals, from Flickr.

- ↑ National Academy of Sciences/ Lincoln Mural.

- ↑ The Landing of Cabrillo at Catalina Island

- ↑ The Building of a Mission

- ↑ Fiesta at a Mission

- ↑ Raising the Flag at Monterey

- ↑ Finding of Gold in '49

- ↑ Photo of Herter portico mural, from Flickr.

- ↑ George Leland Hunter, Tapestries; Their Origin, History And Renaissance, (New York: John Lane Company, 1912), pp. 214-16.

- ↑ The Great Crusade, from Cranbrook Art Museum.

- ↑ "New Martin Beck Theater to Open Tuesday Evening," The New York Times, November 9, 1924.

- ↑ Bob Colacello, "Studios by the Sea," Vanity Fair, January 2000.

- ↑ Ruby Ross & Rayne Adams, The Honest House, (Century Company, 1914), pp. 58-59.

- 1 2 3 The House of Herter Art: Albert and Adele Herter

- ↑ Carol Strickland, "East Hampton Showplace on the Block," The New York Times, July 21, 1991.

- 1 2 3 4 Montecito Journal. Hattie Beresford, The Way It Was: Full Circle: The Story of El Mirasol, January 11, 2007.

- ↑ Ruth St. Denis, An Unfinished Life: An Autobiography, (Dance Horizons, 1969), p. 335.

- ↑ "Akeroyd on House Mural's Committee," The Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), December 15, 1942, p. 4.

External links

- Works by or about Albert Herter at Internet Archive

- House of Herter

- 2blowhards.com: A Less-Known Herter (image of "Woman With Red Hair" (1894); post by Donald Pittenger August 2, 2007

- Santa Barbara Vintage Photo. Images of "El Mirasol"

- The House of Herter Art. 22 minute video of El Mirasol from 1908 to 1969, including Herter art objects

- Historic Photos of Albert Herter's 'The Creeks' in East Hampton

- Cast/Staff Transcription of 1929 playbill for "The Gift of Eternal Life" at the Lobero Theatre, Santa Barbara, California - Mar 20, 1929.

- Invisible Paris. Pro Patria Mori"

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albert Herter. |